AFTERSHOCKS Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

Leonard Bernstein's MASS

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, April 30, at 8:00 Friday, May 1, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 2, at 8:00 Sunday, May 3, at 2:00 Leonard Bernstein’s MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers* Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin Texts from the liturgy of the Roman Mass Additional texts by Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein For a list of performing and creative artists please turn to page 30. *First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes, and will be performed without an intermission. These performances are made possible in part by the generous support of the William Penn Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Presser Foundation. 28 I. Devotions before Mass 1. Antiphon: Kyrie eleison 2. Hymn and Psalm: “A Simple Song” 3. Responsory: Alleluia II. First Introit (Rondo) 1. Prefatory Prayers 2. Thrice-Triple Canon: Dominus vobiscum III. Second Introit 1. In nomine Patris 2. Prayer for the Congregation (Chorale: “Almighty Father”) 3. Epiphany IV. Confession 1. Confiteor 2. Trope: “I Don’t Know” 3. Trope: “Easy” V. Meditation No. 1 VI. Gloria 1. Gloria tibi 2. Gloria in excelsis 3. Trope: “Half of the People” 4. Trope: “Thank You” VII. Mediation No. 2 VIII. Epistle: “The Word of the Lord” IX. Gospel-Sermon: “God Said” X. Credo 1. Credo in unum Deum 2. Trope: “Non Credo” 3. Trope: “Hurry” 4. Trope: “World without End” 5. Trope: “I Believe in God” XI. Meditation No. 3 (De profundis, part 1) XII. -

2020-21-Brochure.Pdf

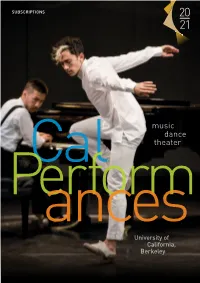

SUBSCRIPTIONS 20 21 music dance Ca l theater Performances University of California, Berkeley Letter from the Director Universities. They exist to foster a commitment to knowledge in its myriad facets. To pursue that knowledge and extend its boundaries. To organize, teach, and disseminate it throughout the wider community. At Cal Performances, we’re proud of our place at the heart of one of the world’s finest public universities. Each season, we strive to honor the same spirit of curiosity that fuels the work of this remarkable center of learning—of its teachers, researchers, and students. That’s why I’m happy to present the details of our 2020/21 Season, an endlessly diverse collection of performances rivaling any program, on any stage, on the planet. Here you’ll find legendary artists and companies like cellist Yo-Yo Ma, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with conductor Gustavo Dudamel, the Mark Morris Dance Group, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and singer/songwriter Angélique Kidjo. And you’ll discover a wide range of performers you might not yet know you can’t live without—extraordinary, less-familiar talent just now emerging on the international scene. This season, we are especially proud to introduce our new Illuminations series, which aims to harness the power of the arts to address the pressing issues of our time and amplify them by shining a light on developments taking place elsewhere on the Berkeley campus. Through the themes of Music and the Mind and Fact or Fiction (please see the following pages for details), we’ll examine current groundbreaking work in the university’s classrooms and laboratories. -

To See the 2018 Tanglewood Schedule

summer 2018 BERNSTEIN CENTENNIAL SUMMER TANGLEWOOD.ORG 1 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ANDRIS NELSONS MUSIC DIRECTOR “That place [Tanglewood] is very dear to my heart, that is where I grew up and learned so much...in 1940 when I first played and studied there.” —Leonard Bernstein (November 1989) SEASONHIGHLIGHTS Throughoutthesummerof2018,Tanglewoodcelebratesthecentennialof AlsoleadingBSOconcertswillbeBSOArtisticPartnerThomas Adès(7/22), Lawrence-born,Boston-bredconductor-composerLeonardBernstein’sbirth. BSOAssistantConductorMoritz Gnann(7/13),andguestconductorsHerbert Bernstein’scloserelationshipwiththeBostonSymphonyOrchestraspanned Blomstedt(7/20&21),Charles Dutoit(8/3&8/5),Christoph Eschenbach ahalf-century,fromthetimehebecameaprotégéoflegendaryBSO (8/26),Juanjo Mena(7/27&29),David Newman(7/28),Michael Tilson conductorSergeKoussevitzkyasamemberofthefirstTanglewoodMusic Thomas(8/12),andBramwell Tovey(8/4).SoloistswiththeBSOalsoinclude Centerclassin1940untilthefinalconcertsheeverconducted,withtheBSO pianistsEmanuel Ax(7/20),2018KoussevitzkyArtistKirill Gerstein(8/3),Igor andTanglewoodMusicCenterOrchestraatTanglewoodin1990.Besides Levit(8/12),Paul Lewis(7/13),andGarrick Ohlsson(7/27);BSOprincipalflute concertworksincludinghisChichester Psalms(7/15), alilforfluteand Elizabeth Rowe(7/21);andviolinistsJoshua Bell(8/5),Gil Shaham(7/29),and orchestra(7/21),Songfest(8/4),theSerenade (after Plato’s “Symposium”) Christian Tetzlaff(7/22). (8/18),andtheBSO-commissionedDivertimentoforOrchestra(also8/18), ThomasAdèswillalsodirectTanglewood’s2018FestivalofContemporary -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs

m fl ^ j- ? i 1 9 if /i THE GREAT OUTDOORS THE GREAT INDOORS Beautiful, spacious country condominiums on 55 magnificent acres with lake, swimming pool and tennis courts, minutes from Tanglewood and the charms of Lenox and Stockbridge. FOR INFORMATION CONTACT (413) 443-3330 1136 Barker Road (on the Pittsfield-Richmond line) GREAT LIVING IN THE BERKSHIRES Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Carl St. Clair and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Seventh Season, 1987-88 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Kidder, President Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman George H. T Mrs. John M. Bradley, Vice-Chairman J. P. Barger, V ice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Michael H. Davis Roderick M. MacDougall David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. August R. Meyer Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick David G. Mugar James F. Cleary Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. George R. Rowland William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. John L. Grandin Richard A. Smith Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney Francis W. Hatch, Jr. Ray Stata Harvey Chet Krentzman Trustees Emeriti Philip K. Allen Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Irving W. Rabb Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Paul C. Reardon Leo L. Beranek Edward M. Kennedy Mrs. George L. Sargent Richard P. Chapman Albert L. Nickerson Sidney Stoneman Abram T. Collier Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John Hoyt Stookey George H.A. Clowes, Jr. John L. Thorndike Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Jay B. Wailes, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Composition Catalog

1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 New York Content & Review Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Marie Carter Table of Contents 229 West 28th St, 11th Floor Trudy Chan New York, NY 10001 Patrick Gullo 2 A Welcoming USA Steven Lankenau +1 (212) 358-5300 4 Introduction (English) [email protected] Introduction 8 Introduction (Español) www.boosey.com Carol J. Oja 11 Introduction (Deutsch) The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc. Translations 14 A Leonard Bernstein Timeline 121 West 27th St, Suite 1104 Straker Translations New York, NY 10001 Jens Luckwaldt 16 Orchestras Conducted by Bernstein USA Dr. Kerstin Schüssler-Bach 18 Abbreviations +1 (212) 315-0640 Sebastián Zubieta [email protected] 21 Works www.leonardbernstein.com Art Direction & Design 22 Stage Kristin Spix Design 36 Ballet London Iris A. Brown Design Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited 36 Full Orchestra Aldwych House Printing & Packaging 38 Solo Instrument(s) & Orchestra 71-91 Aldwych UNIMAC Graphics London, WC2B 4HN 40 Voice(s) & Orchestra UK Cover Photograph 42 Ensemble & Chamber without Voice(s) +44 (20) 7054 7200 Alfred Eisenstaedt [email protected] 43 Ensemble & Chamber with Voice(s) www.boosey.com Special thanks to The Leonard Bernstein 45 Chorus & Orchestra Office, The Craig Urquhart Office, and the Berlin Library of Congress 46 Piano(s) Boosey & Hawkes • Bote & Bock GmbH 46 Band Lützowufer 26 The “g-clef in letter B” logo is a trademark of 47 Songs in a Theatrical Style 10787 Berlin Amberson Holdings LLC. Deutschland 47 Songs Written for Shows +49 (30) 2500 13-0 2015 & © Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. 48 Vocal [email protected] www.boosey.de 48 Choral 49 Instrumental 50 Chronological List of Compositions 52 CD Track Listing LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 2 3 LEONARD BERNSTEIN AT 100 A Welcoming Leonard Bernstein’s essential approach to music was one of celebration; it was about making the most of all that was beautiful in sound. -

Anthony Braxton

Call for Papers 50+ Years of Creative Music: Anthony Braxton – Composer, Multi-Instrumentalist, Music Theorist International Conference June 18th‒20th 2020 Institute for Historical Musicology of the University Hamburg Neue Rabenstr. 13 | 20354 Hamburg | Germany In June, 2020, Anthony Braxton will be celebrating his 75th birthday. For more than half a century he has played a key role in contemporary and avant-garde- music as a composer, multi-instrumentalist, music theorist, teacher, mentor and visionary. Inspired by Jazz, European art music, and music of other cultures, Braxton labels his output ‘Creative Music’. This international conference is the first one dealing with his multifaceted work. It aims to discuss different research projects concerned with Braxton’s compositional techniques as well as his instrumental- and music-philosophical thinking. The conference will take place from June 18th to 20th 2020 at the Hamburg University, Germany. During the first half of his working period, dating from 1967 to the early 1990s, Braxton became a ‘superstar of the jazz avant-garde’ (Bob Ostertag), even though he acted as a non-conformist and was thus perceived as highly controversial. In this period he also became a member of the AACM, the band Circle, and recorded music for a variety of mostly European minors as well as for the international major Arista. Furthermore, he developed his concepts of ‘Language Music’ for solo-artist and ‘Co-ordinate Music’ for small ensembles, composed his first pieces for the piano and orchestra and published his philosophical Tri-Axium Writings (3 volumes) and Composition Notes (5 volumes). These documents remain to be thoroughly analyzed by the musicological community. -

Orchestra Bells As a Chamber and Solo Instrument: a Survey Of

ORCHESTRA BELLS AS A CHAMBER AND SOLO INSTRUMENT: A SURVEY OF WORKS BY STEVE REICH, MORTON FELDMAN, FRANCO DONATONI, ROBERT MORRIS, MARTA PTASZYŃSKA, WILL OGDON, STUART SAUNDERS SMITH, LAFAYETTE GILCHRIST AND ROSCOE MITCHELL Mark Samuel Douglass, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2016 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Joseph Klein, Relative Field Professor David Bard-Schwarz, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies and Dean of the College of Music Douglass, Mark Samuel. Orchestra Bells as a Chamber and Solo Instrument: A Survey of Works by Steve Reich, Morton Feldman, Franco Donatoni, Robert Morris, Marta Ptaszyńska, Will Ogdon, Stuart Saunders Smith, Lafayette Gilchrist and Roscoe Mitchell. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2016, 96 pp., 73 musical examples, 11 figures, references, 59 titles. This dissertation considers the use of orchestra bells as a solo instrument. I use three examples taken from chamber literature (Drumming by Steve Reich, Why Patterns? by Morton Feldman, and Ave by Franco Donatoni) to demonstrate uses of the instrument in an ensemble setting. I use six solo, unaccompanied orchestra bell pieces (Twelve Bell Canons by Robert Morris, Katarynka by Marta Ptaszyńska, Over by Stuart Saunders Smith, A Little Suite and an Encore Tango by Will Ogdon, Breaks Through by Lafayette Gilchrist, and Bells for New Orleans by Roscoe Mitchell) to illustrate the instrument’s expressive, communicative ability. In the discussion of each piece, I include brief background information, the composer’s m usical language in the piece and performance considerations. I interviewed composers of these solo works to complete the research for this document to discuss their musical language and their thoughts on writing for solo orchestra bells. -

6. the Evolving Role of Music Journalism Zachary Woolfe and Alex Ross

Classical Music Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges Classical Music This kaleidoscopic collection reflects on the multifaceted world of classical music as it advances through the twenty-first century. With insights drawn from Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges leading composers, performers, academics, journalists, and arts administrators, special focus is placed on classical music’s defining traditions, challenges and contemporary scope. Innovative in structure and approach, the volume comprises two parts. The first provides detailed analyses of issues central to classical music in the present day, including diversity, governance, the identity and perception of classical music, and the challenges facing the achievement of financial stability in non-profit arts organizations. The second part offers case studies, from Miami to Seoul, of the innovative ways in which some arts organizations have responded to the challenges analyzed in the first part. Introductory material, as well as several of the essays, provide some preliminary thoughts about the impact of the crisis year 2020 on the world of classical music. Classical Music Classical Classical Music: Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges will be a valuable and engaging resource for all readers interested in the development of the arts and classical music, especially academics, arts administrators and organizers, and classical music practitioners and audiences. Edited by Paul Boghossian Michael Beckerman Julius Silver Professor of Philosophy Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor and Chair; Director, Global Institute for of Music and Chair; Collegiate Advanced Study, New York University Professor, New York University This is the author-approved edition of this Open Access title. As with all Open Book publications, this entire book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

The Concerto for Bassoon by Andrzej Panufnik

THE CONCERTO FOR BASSOON BY ANDRZEJ PANUFNIK: RELIGION, LIBERATION AND POSTMODERNISM Janelle Ott Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2016 APPROVED: Kathleen Reynolds, Major Professor Eugene Cho, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Ott, Janelle. The Concerto for Bassoon by Andrzej Panufnik: Religion, Liberation, and Postmodernism. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2016, 128 pp., 2 charts, 23 musical examples, references, 88 titles. The Concerto for Bassoon by Andrzej Panufnik is a valuable addition to bassoon literature. It provides a rare opportunity for the bassoon soloist to perform a piece which is strongly programmatic. The purpose of this document is to examine the historical and theoretical context of the Concerto for Bassoon with special emphasis drawn to Panufnik’s understanding of religion in connection with Polish national identity and the national struggle for democratic independence galvanized by the murder of Father Jerzy Popiełuszko in 1984. Panufnik’s relationship with the Polish communist regime, both prior to and after his 1954 defection to England, is explored at length. Each of these aspects informed Panufnik’s compositional approach and the expressive qualities inherent in the Concerto for Bassoon. The Concerto for Bassoon was commissioned by the Polanki Society of Milwaukee, Wisconsin and was premiered by the Milwaukee Chamber Players, with Robert Thompson as the soloist. While Panufnik intended the piece to serve as a protest against the repression of the Soviet government in Poland, the U. S.