Russian Views of US Alliances in Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Integration of Siberian Regional Markets

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Spatial Integration of Siberian Regional Markets Gluschenko, Konstantin Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk State University 2 April 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/85667/ MPRA Paper No. 85667, posted 02 Apr 2018 23:10 UTC Spatial Integration of Siberian Regional Markets Konstantin Gluschenko Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEIE SB RAS), and Novosibirsk State University Novosibirsk, Russia E-mail address: [email protected] This paper studies market integration of 13 regions constituting Siberia with one another and all other Russian regions. The law of one price serves as a criterion of market integration. The data analyzed are time series of the regional costs of a basket of basic foods (staples basket) over 2001–2015. Pairs of regional markets are divided into four groups: perfectly integrated, conditionally integrated, not integrated but tending towards integration (converging), and neither integrated nor converging. Nonlinear time series models with asymptotically decaying trends describe price convergence. Integration of Siberian regional markets is found to be fairly strong; they are integrated and converging with about 70% of country’s regions (including Siberian regions themselves). Keywords: market integration, law of one price; price convergence; nonlinear trend; Russian regions. JEL classification: C32, L81, P22, R15 Prepared for the Conference “Economy of Siberia under Global Challenges of the XXI Century” dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the IEIE SB RAS; Novosibirsk, Russia, June 18–20, 2018. 1. Introduction The national product market is considered as a system with elements being its spatial segments, regional markets. -

The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) : an Historical

Public Diplomacy Division Room Nb123 B-1110 Brussels Belgium Tel.: +32(0)2 707 4414 / 4541 (A/V) Fax: +32(0)2 707 4249 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.nato.int/library Acquisitions List June 2013 New Books and Journal Articles Liste d’acquisitions Juin 2013 Nouveaux livres et articles de revues Division de la Diplomatie Publique Bureau Nb123 B-1110 Bruxelles Belgique Tél.: +32(0)2 707 4414 / 4541 (A/V) Fax: +32(0)2 707 4249 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.nato.int/library How to borrow items from the list below : As a member of the NATO HQ staff you can borrow books (Type: M) for one month, journals (Type: ART) and reference works (Type: REF) for one week. Individuals not belonging to NATO staff can borrow books through their local library via the interlibrary loan system. How to obtain the Multimedia Library publications : All Library publications are available both on the NATO Intranet and Internet websites. Comment emprunter les documents cités ci-dessous : En tant que membre du personnel de l'OTAN vous pouvez emprunter les livres (Type: M) pour un mois, les revues (Type: ART) et les ouvrages de référence (Type: REF) pour une semaine. Les personnes n'appartenant pas au personnel de l'OTAN peuvent s'adresser à leur bibliothèque locale et emprunter les livres via le système de prêt interbibliothèques. Comment obtenir les publications de la Bibliothèque multimédia : Toutes les publications de la Bibliothèque sont disponibles sur les sites Intranet et Internet de l’OTAN. -

Dartmouth Conf Program

The Dartmouth Conference: The First 50 Years 1960—2010 Reminiscing on the Dartmouth Conference by Yevgeny Primakov T THE PEAK OF THE COLD WAR, and facilitating conditions conducive to A the Dartmouth Conference was one of economic interaction. the few diversions from the spirit of hostility The significance of the Dartmouth Confer- available to Soviet and American intellectuals, ence relates to the fact that throughout the who were keen, and able, to explore peace- cold war, no formal Soviet-American contact making initiatives. In fact, the Dartmouth had been consistently maintained, and that participants reported to huge gap was bridged by Moscow and Washington these meetings. on the progress of their The composition of discussion and, from participants was a pri- time to time, were even mary factor in the success instructed to “test the of those meetings, and it water” regarding ideas took some time before the put forward by their gov- negotiating teams were ernments. The Dartmouth shaped the right way. At meetings were also used first, in the early 1970s, to unfetter actions under- the teams had been led taken by the two countries by professionally quali- from a propagandist connotation and present fied citizens. From the Soviet Union, political them in a more genuine perspective. But the experts and researchers working for the Insti- crucial mission for these meetings was to tute of World Economy and International establish areas of concurring interests and to Relations and the Institute of U.S. and Cana- attempt to outline mutually acceptable solutions dian Studies, organizations closely linked to to the most acute problems: nuclear weapons Soviet policymaking circles, played key roles. -

Forests on Fire: 'No Attempt Will Be Made to Extinguish 219 Million Hectares of Burning Trees'

http://siberiantimes.com/ecology/others/news/n0688-forests-on-fire-no-attempt-will-be-made-to- extinguish-219-million-hectares-of-burning-trees/ Forests on fire: 'no attempt will be made to extinguish 219 million hectares of burning trees' By Olga Gertcyk 29 May 2016 A quarter of all Russian forests, 89% of stocks in Sakha Republic, could be left to burn, even though they are essential to fight global warming. Some 86% of forest in Sakha - also known as Yakutia, and the largest constituent of the Russian Federation - is deemed to fall into the category of 'distant and hard-to-reach territories'. Picture: Alexander Krivoshapkin These vast tracts of forest have been labelled 'distant and hard-to-reach territories', and as such it is officially permitted not to extinguish forest fires if they do not constitute a threat to settlements or if a fire fighting operation is extremely expensive. At the same time, there is official recognition that some regions in Siberia are underreporting the extent of forest fires for 'political reasons', an accusation long made by environmental campaigners. Some 86% of forest in Sakha - also known as Yakutia, and the largest constituent of the Russian Federation - is deemed to fall into the category of 'distant and hard-to-reach territories', according to reports. A new decree in Sakha Republic says the emergency services may stop extinguishing fires in hard-to-reach territories if there is no threat to residential areas. Pictures: Aviarosleskhoz Some 219 million hectares - or 2.19 million square kilometres, a larger area than either Saudi Arabia or Greenland - is covered by the definition. -

Social and Behavioural Sciences

European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences EpSBS www.europeanproceedings.com e-ISSN: 2357-1330 DOI: 10.15405/epsbs.2021.05.02.156 MSC 2020 International Scientific and Practical Conference «MAN. SOCIETY. COMMUNICATION» REGIONAL CONCEPTS VERBALIZATION IN TRANSBAIKAL TERRITORY MEDIA DISCOURSE Yulia Shchurina (a)*, Maria Vyrupaeva (b), Anastasia Ivanova (c) *Corresponding author (a) Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russian Federation, [email protected] (b) Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russian Federation (c) Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russian Federation Abstract The article deals with the features of locally marked concepts objectification of the regional level, conventionally called regional concepts, in the media space of the Transbaikal Krai territory. The authors offer their own definition of the concept “regional concept”. The study of locally marked concepts and their verbalization in regional media texts is carried out within the framework of a cognitive language approach. The paper presents concepts that represent the image of Transbaikal in the modern media sphere: “Guran”, “bagulnik” and “Sagaalgan”; they are described by means of conceptual analysis, which involves the study of the verbal representations semantics of these concepts, and contextual analysis, which actualizes the elements of the concepts meaning when creating lexemes-representatives in certain contexts. Identifying the content of the conceptual and figurative components of the concepts “Guran”, “bagulnik” and “Sagaalgan”, the authors determine the typical characteristics of the regional concept, suggesting that they are considered key ones for conducting research of this kind: recognition, territorial consolidation, symbolism and high frequency of use in a positive evaluation context. The conclusion is made about the close semantic relationship and interdependence of regional concepts that form a larger conceptual combination – hyperconcept (“Transbaikal”). -

Title Notes on Carnivore Fossils from the Pliocene Udunga Fauna

Notes on carnivore fossils from the Pliocene Udunga fauna, Title Transbaikal area, Russia Ogino, Shintaro; Nakaya, Hideo; Takai, Masanaru; Fukuchi, Author(s) Akira Citation Asian paleoprimatology (2009), 5: 45-60 Issue Date 2009 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/199776 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Asian Paleoprimatology, vol. 5: 45-60 (2008) Kyoto University Primate Research Institute Notes on carnivore fossils from the Pliocene Udunga fauna, Transbaikal area, Russia Shintaro Ogino1*, Hideo Nakaya2, Masanaru Takai1, Akira Fukuchi2, 3 1Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University. Inuyama 484-8506, Japan 2Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan 3Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, Okayama 700-8530, Japan *Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract We provide notes of carnivore fossils from the middle Pliocene Udunga fauna, Transbaikal area, Russia. The fossil carnivore assemblage consists of more than 200 specimens including eleven genera. Ursus, Parailurus, Parameles, and Ferinestrix are representative of the animals of thermophilic forest biotopes. On the other hand, Chasmaporthetes and Pliocrocuta are probably specialized in open environment. The prosperity both in foresal and semiarid carnivores indicate that the Udunga fauna is comprised of mosaic elements. Introduction The fauna dating back to the Pliocene in Udunga, Transbaikalia, Russia, comprises eleven species of mammals, such as rodents, lagomorphs, carnivores, perissodactyls, artiodactyls, and elephants (Kalmykov, 1989, 1992, 2003; Kalmykov and Maschenko, 1992, 1995 Vislobokova et al., 1993, 1995;; Erbajeva et al., 2003). The Udunga site is located on the left bank of the Temnik River, the tributary of the Selenga River in the vicinity of Udunga village (Figure 1). -

N a T O's G L O B a L M I S S I O N I N T H E

THE MANFRED WÖRNER FELLOWSHIP OF NATO 1998-1999 THE ATLANTIC CLUB OF BULGARIA NN AA TT OO’’ss GG LL OO BB AA LL MM II SS SS II OO NN II NN TT HH EE 2211SSTT CC EE NN TT UU RR YY STRATEGIC STUDY Supported by: THE GERMAN MARSHALL FUND OF THE UNITED STATES Project Director and Author of the Text: Dr. Stefan Popov Working Group: Dr. Lyubomir Ivanov Dr. Solomon Passy Marianna Panova, MIA Marin Mihaylov Sofia May 2000 THE ATLANTIC CLUB OF BULGARIA 1998-1999 MANFRED WŐRNER FELLOWSHIP N A T O ’ s G L O B A L M I S S I O N I N T H E 2 1 S T C E N T U R Y Table of Contents ABSTRACT 1 PREFACE 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4 INTRODUCTION 5 THE ENLARGEMENT DEBATE IN THE 1990s 8 Historical Context: Setting the Stage 8 Critical Position Toward the Debate 11 Europe: Divided or United? 14 Extended Deterrence vs. Diminished Credibility 16 Military Doctrine vs. Military Spending 18 Expanded NATO, Expanded Security Risks? 19 Russia: Friend or Foe? 21 American “Manifest Destiny” 22 Summary Reflection on the Enlargement Debate 24 CONCEPTUAL DIMENSIONS: DEFENSE VS. SECURITY 27 Ideal Types Approach in International Affairs 27 A Concise Definition of the 1989 Epochal Change 30 Subject-Origin of Threat 33 Risky Factors and Situations 40 NATO’s Fundamental Identity Dilemma 44 Remark on a Negative Perception of Enlargement 46 Summary Reflection on Conceptualizing Security 48 HISTORICAL DIMENSIONS: THE YUGOSLAV WARS 52 The Early Yugoslav Crisis: A New Institutional Chaos 52 (a) Confusion Regarding Fundamentals 53 (b) European Institutions: Taken by Surprise 55 (c) UN and the Others 58 (d) Diagnosis: Institutional Paralysis 60 Kosovo: A New Kind of War 62 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ NATO’s GLOBAL MISSION IN THE 21ST CENTURY THE ATLANTIC CLUB OF BULGARIA 1998-1999 MANFRED WŐRNER FELLOWSHIP (a) A New Concept of Security Implied 63 (b) Human rights vs. -

Recent Scholarship from the Buryat Mongols of Siberia

ASIANetwork Exchange | fall 2012 | volume 20 |1 Review essay: Recent Scholarship from the Buryat Mongols of Siberia Etnicheskaia istoriia i kul’turno-bytovye traditsii narodov baikal’skogo regiona. [The Ethnic History and the Traditions of Culture and Daily Life of the Peoples of the Baikal Region] Ed. M. N. Baldano, O. V. Buraeva and D. D. Nimaev. Ulan-Ude: Institut mongolovedeniia, buddologii i tibetologii Sibirskogo otdeleniia Rossiiskoi Akademii nauk, 2010. 243 pp. ISBN 978-5-93219-245-0. Keywords Siberia; Buryats; Mongols Siberia’s vast realms have often fallen outside the view of Asian Studies specialists, due perhaps to their centuries-long domination by Russia – a European power – and their lack of elaborately settled civilizations like those elsewhere in the Asian landmass. Yet Siberia has played a crucial role in Asian history. For instance, the Xiongnu, Turkic, and Mongol tribes who frequently warred with China held extensive Southern Siberian territories, and Japanese interventionists targeted Eastern Siberia during the Russian Civil War (1918- 1921). Moreover, far from being a purely ethnic-Russian realm, Siberia possesses dozens of indigenous Asian peoples, some of whom are clearly linked to other, more familiar Asian nations: for instance, the Buryats of Southeastern Siberia’s Lake Baikal region share par- ticularly close historic, ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural ties with the Mongols. The Buryats, who fell under Russian rule over the seventeenth century, number over 400,000 and are the largest native Siberian group. Most dwell in the Buryat Republic, or Buryatia, which borders Mongolia to the south and whose capital is Ulan-Ude (called “Verkheneu- dinsk” during the Tsarist period); others inhabit Siberia’s neighboring Irkutsk Oblast and Zabaikal’skii Krai (formerly Chita Oblast), and tens of thousands more live in Mongolia and China. -

Selected Multilateral Organizations

SELECTED MULTILATERAL ORGANIZATIONS MULTILATERAL INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS IN WHICH THE UNITED STATES PARTICIPATES Explanatory note: The United States participates in the organizations named below in accordance with the provisions of treaties, other international agreements, congressional legislation, or executive arrangements. In some cases, no financial contribution is involved. Various commissions, councils, or committees subsidiary to the organizations listed here are not named separately on this list. These include the international bodies for narcotics control, which are subsidiary to the United Nations. I. United Nations, Specialized Agencies, United Nations Mission of Observers in and International Atomic Energy Agency Tajikistan Food and Agricultural Organization United Nations Mission to Prevlaka International Atomic Energy Agency United Nations Mission for the International Civil Aviation Organization Referendum in Western Sahara International Labor Organization United Nations Observer Mission in International Maritime Organization Angola United Nations Observer Mission in International Telecommunication Union Georgia United Nations United Nations Transitional Universal Postal Union Administration in East Timor World Health Organization United Nations Truce Supervision World Intellectual Property Organization Organization (Middle East) World Meteorological Organization III. Inter-American Organizations II. Peacekeeping Inter-American Indian Institute United Nations Disengagement Observer Inter-American Institute for Cooperation -

Tibet Through the Eyes of a Buryat: Gombojab Tsybikov and His Tibetan Relations

ASIANetwork Exchange | Spring 2013 | volume 20 | 2 Tibet through the Eyes of a Buryat: Gombojab Tsybikov and his Tibetan relations Ihor Pidhainy Abstract: Gombojab Tsybikov (1873-1930), an ethnic Buryat from Russia, was a young scholar of oriental studies when he embarked on a scholarly expedition to Tibet. Under the sponsorship of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, Tsybikov spent over a year in Lhasa (1900-1902), gathering materials and tak- ing photographs of the city and its environs, eventually introducing Tibet both academically and visually to the outside world. This paper examines the context of Tsybikov’s trip within the larger issues of scholarship, international politics, and modernization. In addition, it argues that Tsybikov was an example of a man caught between identities – an ethnic Buryat raised as a Buddhist, and a Russian citizen educated and patronized by that nation. He was, in a sense, the epitome of modern man. Keywords Tsybikov; Tibet; travel; Buryat; Russia; Buddhism; identity Gombojab Tsybikov’s (1873-1930) life and writings deal with the complex weavings of Ihor Pidhainy is Assistant identity encountered in the modern period.1 His faith and nationality positioned him as Professor of History at Marietta an “Asian”, while his education and employment within the Russian imperial framework College. His research focuses on the place of the individual in the marked him as “European.” His historical significance lies in his scholarly account of his complex of social, intellectual trip to Tibet. This paper examines Tsybikov’s relationship to Tibet, particularly in the period and political forces, with areas between 1899 and 1906, and considers how his position as an actor within the contexts of and periods of interest including empire, nation, and religious community made him an example of the new modern man.2 Ming dynasty China and Eura- sian interactions from the 18th The Buryats to 20th centuries. -

Lake Baikal Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

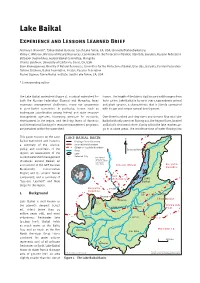

Lake Baikal Experience and Lessons Learned Brief Anthony J. Brunello*, Tahoe-Baikal Institute, South Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, [email protected] Valery C. Molotov, Ministry of Natural Resources, Committee for the Protection of Baikal, Ulan Ude, Buryatia, Russian Federation Batbayar Dugherkhuu, Federal Baikal Committee, Mongolia Charles Goldman, University of California, Davis, CA, USA Erjen Khamaganova, Ministry of Natural Resources, Committee for the Protection of Baikal, Ulan Ude, Buryatia, Russian Federation Tatiana Strijhova, Baikal Foundation, Irkutsk, Russian Federation Rachel Sigman, Tahoe-Baikal Institute, South Lake Tahoe, CA, USA * Corresponding author The Lake Baikal watershed (Figure 1), a critical watershed for France. The length of the lake is 636 km and width ranges from both the Russian Federation (Russia) and Mongolia, faces 80 to 27 km. Lake Baikal is home to over 1,500 endemic animal enormous management challenges, many not uncommon and plant species, a characteristic that is closely connected in post-Soviet economies. In particular, issues such as with its age and unique natural development. inadequate coordination among federal and state resource management agencies, increasing pressure for economic Over three hundred and sixty rivers and streams fl ow into Lake development in the region, and declining levels of domestic Baikal with only one river fl owing out, the Angara River, located and international funding for resource management programs, on Baikal’s northwest shore. Clarity within the lake reaches 40- are -

Burgeoning Sino-Russian Economic Relations and the Russian Far East: Prospects and Challenges Asst

SESSION 2A: International Trade 59 Burgeoning Sino-Russian Economic Relations and the Russian Far East: Prospects and Challenges Asst. Prof. Dr. Çağrı Erdem (Doğuş University, Turkey) Abstract The colossal economic transformations and political intrusions had been affecting brutally China and the Soviet Union in the final decades of the twentieth century. Currently, Russia is a gigantic power, struggling to rebuild its economic base in an era of globalization. There are a number of significant difficulties of guaranteeing a stable domestic order due to demographic shifts, economic changes, and institutional weaknesses. On the other hand, the economic rise of China has attracted a great deal of attention and labeled as a success story by the Western world. The current growth of the Chinese economy is of immense importance for the global economy. Both nations are part of the world’s largest and fastest-growing emerging markets—member of the BRIC. Their respective GDPs are growing at an impressive rate by any global standards. Relations between China and Russia have evolved dramatically throughout the twentieth century. However, it would be fair to argue that during the past decade China and Russia have made a number of efforts to strengthen bilateral ties and improve cooperation on a number of economic/political/diplomatic fronts. The People's Republic of China and the Russian Federation maintain exceptionally close and friendly relations, strong geopolitical and regional cooperation, and significant levels of trade. This paper will explore the burgeoning economic and political relationships between the two nations and place the Russian Far East in the context of Russia's bilateral relations with China in order to examine the political, economic, and security significance of the region for both sides.