Leaving Little Havana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aperitivos ~ Check out Our Wine and Drinks Card~

Aperitivos ~ Check out our wine and drinks card~ Aperitif 5,00 Hugo - prosecco, elderflower, mint, lemon peel Agua de Valencia - orange juice, vodka, gin, prosecco Aperol Spritz - aperol, prosecco, orange juice, soda Viper Hard Seltzer - sparkling spring water with 4% alcohol and lime Gin & Tonics 9,00 Lemon - tanqueray ten gin, lemon, juniper Herbs & Spices - tanqueray london dry, juniper, clove, cardamom, orange Ginger Rosemary - gordon’s london dry, ginger, lemon, rosemary Cocktails 8,00 Mojito - rum, lime, sugar, mint, soda water Cuba Libre - rum, lime, cola 43 Sour - licor 43, lemon, aquafaba, sugar water Sangria 5,00 / 9,50 / 18,00 Sangria Tinto - red wine, various drinks, fruits Alcohol free 5,00 Pimento - ginger beer, ginger tonic, chili and spices Hugo 0.0 - elderflower, lemon peel, mint, sprite, ice Nojito - mint, lime, sugar, soda water, apple juice The Fortress of the Alhambra, Granada Menu ~ suggestions ~ “under the Mediterranean sun” Menu Alhambra 35,00 “Take your time to enjoy tastings in multiple courses” seasoned pita bread - lebanese flat bread - turkish bread hummus - aioli - muhammarah - olives - smoked almonds manchego membrillo- feta - iberico chorizo - iberico paletta dades with pork belly - fried eggplant shorbat aldas - falafel casero - albóndigas vegetariano croquetas iberico - calamares köfta - tajine pollo - gambas al ajillo couscous harissa deliciosos dulces Menu Moro 32,00 “tapas and mezze menu in multiple servings” First round seasoned pita bread with aioli and muhamarah Second round tasting of multiple -

Article Description EAN/UPC ARTIC ZERO TOFFEE CRUNCH 16 OZ 00852244003947 HALO TOP ALL NAT SMORES 16 OZ 00858089003180 N

Article Description EAN/UPC ARTIC ZERO TOFFEE CRUNCH 16 OZ 00852244003947 HALO TOP ALL NAT SMORES 16 OZ 00858089003180 NESTLE ITZAKADOOZIE 3.5 OZ 00072554211669 UDIS GF BREAD WHOLE GRAIN 24 OZ 00698997809302 A ATHENS FILLO DOUGH SHEL 15 CT 00072196072505 A B & J STRW CHSCK IC CUPS 3.5 OZ 00076840253302 A F FRZN YGRT FRCH VNLL L/FAT 64 OZ 00075421061022 A F I C BLACK WALNUT 16 OZ 00075421000021 A F I C BROWNIES & CREAM 64 OZ 00075421001318 A F I C HOMEMADE VANILLA 16 OZ 00075421050019 A F I C HOMEMADE VANILLA 64 OZ 00075421051016 A F I C LEMON CUSTARD 16 OZ 00075421000045 A F I C NEAPOLITAN 16 OZ 00075421000038 A F I C VANILLA 16 OZ 00075421000014 A F I C VANILLA 64 OZ 00075421001011 A F I C VANILLA FAT FREE 64 OZ 00075421071014 A F I C VANILLA LOW FAT 64 OZ 00075421022016 A RHODES WHITE DINN ROLLS 96 OZ 00070022007356 A STF 5CHS LASAGNA DBL SRV 18.25 OZ 00013800447197 ABSOLUTELY GF VEG CRST MOZZ CH 6 OZ 00073490180156 AC LAROCCO GRK SSM PZ 12.5 OZ 00714390001201 AF SAVORY TKY BRKFST SSG 7 OZ 00025317694001 AGNGRN BAGUETE ORIGINAL GF 15 OZ 00892453001037 AGNST THE GRAIN THREE CHEESE PIZZA 24 OZ 00892453001082 AGNST THE GRN PESTO PIZZA GLTN FREE 24OZ 00892453001105 AJINOMOTO FRIED RICE CHICKEN 54 OZ 00071757056732 ALDENS IC FRENCH VANILLA 48 OZ 00072609037893 ALDENS IC LT VANILLA 48 OZ 00072609033130 ALDENS IC SALTED CARAMEL 48 OZ 00072609038326 ALEXIA ARBYS SEASND CRLY FRIES 22 OZ 00043301370007 ALEXIA BTRNT SQSH BRN SUG SS 12OZ 00034183000052 ALEXIA BTRNT SQSH RISO PARM SS 12OZ 00034183000014 ALEXIA CLFLWR BTR SEA SALT 12 OZ 00034183000045 -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

Authentic Jamaican Jerk Chicken

Authentic Jamaican Jerk Chicken Yield: Serves 4 Ingredients: 4 lbs Bone In Chicken Pieces - can substitute 4 lbs boneless/skinless chicken breasts Jerk Marinade: 6 Fresh Scotch Bonnet Peppers - chopped 3 medium Yellow Onions - chopped 8-12 cloves Fresh Garlic - crushed ½ inch piece Fresh Ginger - rough chopped 1 Cup Fresh Squeezed Orange Juice 1 Cup Cane Vinegar ½ Cup Soy Sauce ½ Cup Extra Virgin Olive Oil 2 Tbs Kosher Salt 2 Tbs Granulated Sugar 2 Tbs ground Allspice 2 Tbs ground dried Thyme 2 tsp fresh ground Black Pepper 2 tsp ground Cinnamon 2 tsp ground Nutmeg Juice of one Lime Preparation: 1) Place all of the marinade ingredients into a blender or food processor and purée into a smooth paste - Place a cup or two of marinade into an airtight container and save for service 2) Place the chicken pieces in a large zip-top bag (use two if necessary) and cover with remaining marinade - Massage into chicken pieces and then remove as much air as possible from the bag(s) and place in refrigerator for a minimum 8 hours (overnight for better results) - Turn bag(s) a couple of times during marinating -NEXT DAY- 3) Preheat oven to 450ºF -OR- Prepare grill* (if grilling, skip to step 5) 4) Remove chicken from marinade (save remaining marinade for basting) and place in a single layer on a broiler pan - Bake on the center rack of the oven for 7-8 minutes to a side or until juices run clear) - Baste with remaining marinade as desired (skip to step 6) 5) Remove chicken from marinade (save remaining marinade for basting) and grill over medium heat flipping regularly and basting with remaining marinade until cooked through (internal temp should be between 160-170ºF and juices should run clear) 6) Serve with reserved marinade to use as a dip along with festival dumplings and salad of choice - OR- Rice and peas and hardo bread * Use of a charcoal grill is recommended - Pimento wood is traditional (look for pimento wood at specialty grill shops) Taz Doolittle www.TazCooks.com . -

Resistance, Language and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks History: Faculty Publications History Summer 2016 The tE ymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/hst_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Pryor, Elizabeth Stordeur, "The tE ymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North" (2016). History: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/hst_facpubs/4 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] The Etymology of Nigger: Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor Journal of the Early Republic, Volume 36, Number 2, Summer 2016, pp. 203-245 (Article) Published by University of Pennsylvania Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jer.2016.0028 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/620987 Access provided by Smith College Libraries (5 May 2017 18:29 GMT) The Etymology of Nigger Resistance, Language, and the Politics of Freedom in the Antebellum North ELIZABETH STORDEUR PRYOR In 1837, Hosea Easton, a black minister from Hartford, Connecticut, was one of the earliest black intellectuals to write about the word ‘‘nigger.’’ In several pages, he documented how it was an omni- present refrain in the streets of the antebellum North, used by whites to terrorize ‘‘colored travelers,’’ a term that elite African Americans with the financial ability and personal inclination to travel used to describe themselves. -

Download Brochure

Because Flavor is Everything Victoria Taylor’s® Seasonings ~ Jars & Tins Best Sellers Herbes de Provence is far more flavorful than the traditional variety. Smoky Paprika Chipotle is the first seasoning blend in the line with A blend of seven herbs is highlighted with lemon, lavender, and the the distinctive smoky flavor of mesquite. The two spices most famous added punch of garlic. It’s great with chicken, potatoes, and veal. Jar: for their smoky character, chipotle and smoked paprika, work together 00105, Tin: 01505 to deliver satisfying flavor. Great for chicken, tacos, chili, pork, beans & rice, and shrimp. Low Salt. Jar: 00146, Tin: 01546 Toasted Sesame Ginger is perfect for stir fry recipes and flavorful crusts on tuna and salmon steaks. It gets its flavor from 2 varieties of Ginger Citrus for chicken, salmon, and grains combines two of toasted sesame seeds, ginger, garlic, and a hint of red pepper. Low Victoria’s favorite ingredients to deliver the big flavor impact that Salt. Jar: 00140, Tin: 01540 Victoria Gourmet is known for. The warm pungent flavor of ginger and the tart bright taste of citrus notes from orange and lemon combine for Tuscan combines rosemary with toasted sesame, bell pepper, and a delicious taste experience. Low Salt. Jar: 00144, Tin: 01544 garlic. Perfect for pasta dishes and also great on pork, chicken, and veal. Very Low Salt. Jar: 00106. Tin: 01506 Honey Aleppo Pepper gets its flavor character from a truly unique combination of natural honey granules and Aleppo Pepper. On the Sicilian is a favorite for pizza, red sauce, salads, and fish. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Erich Poncza The Impact of American Minstrelsy on Blackface in Europe Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2017 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 1 I would like to thank my supervisor Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his guidance and help in the process of writing my bachelor´s theses. 2 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………..………....……5 1. Stereotyping………………………………………..…….………………..………….6 2. Origins of Blackface………………………………………………….…….……….10 3. Blackface Caricatures……………………………………………………………….13 Sambo………………………………………………………….………………14 Coon…………………………………………………………………….……..15 Pickaninny……………………………………………………………………..17 Jezebel…………………………………………………………………………18 Savage…………………………………………………………………………22 Brute……………………………………………………….………........……22 4. European Blackface and Stereotypes…………………………..……….….……....26 Minstrelsy in England…………………………………………………………28 Imagery………………………………………………………………………..31 Blackface………………………………………………………..…………….36 Czech Blackface……………………………………………………………….40 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….44 Images…………………………………………………………………………………46 Works Cited………………………………………………………………….………..52 Summary………………………………………………………….……………………59 Resumé……………………………………………………………………..………….60 3 Introduction Blackface is a practice that involves people, mostly white, painting their faces -

Spice Basics

SSpicepice BasicsBasics AAllspicellspice Allspice has a pleasantly warm, fragrant aroma. The name refl ects the pungent taste, which resembles a peppery compound of cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg or mace. Good with eggplant, most fruit, pumpkins and other squashes, sweet potatoes and other root vegetables. Combines well with chili, cloves, coriander, garlic, ginger, mace, mustard, pepper, rosemary and thyme. AAnisenise The aroma and taste of the seeds are sweet, licorice like, warm, and fruity, but Indian anise can have the same fragrant, sweet, licorice notes, with mild peppery undertones. The seeds are more subtly fl avored than fennel or star anise. Good with apples, chestnuts, fi gs, fi sh and seafood, nuts, pumpkin and root vegetables. Combines well with allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, fennel, garlic, nutmeg, pepper and star anise. BBasilasil Sweet basil has a complex sweet, spicy aroma with notes of clove and anise. The fl avor is warming, peppery and clove-like with underlying mint and anise tones. Essential to pesto and pistou. Good with corn, cream cheese, eggplant, eggs, lemon, mozzarella, cheese, olives, pasta, peas, pizza, potatoes, rice, tomatoes, white beans and zucchini. Combines well with capers, chives, cilantro, garlic, marjoram, oregano, mint, parsley, rosemary and thyme. BBayay LLeafeaf Bay has a sweet, balsamic aroma with notes of nutmeg and camphor and a cooling astringency. Fresh leaves are slightly bitter, but the bitterness fades if you keep them for a day or two. Fully dried leaves have a potent fl avor and are best when dried only recently. Good with beef, chestnuts, chicken, citrus fruits, fi sh, game, lamb, lentils, rice, tomatoes, white beans. -

Jamaican Jerk Sweet Potato & Black Bean Curry

Jamaican Jerk Sweet Potato & Black Bean Curry Serve your vegetable curry Caribbean style, flavoured with thyme, jerk seasoning and red peppers - great with rice! Ingredients White Rice Jerk Seasoning Red Capsicum Fresh Coriander Black Beans Ginger Sweet Potato Brown Onion Vegetable Stock Brown Sugar Red Grape Vinegar Chopped Tomatoes Fresh Thyme Pantry Items Olive Oil. Salt and Pepper. Recipe #271 Livefreshr Cookline Bring 2 saucepans of water to the 0 boil. Add salt to one and vegetable stock to the other. Peel and roughly chop the brown 0.5 onion, ginger and sweet potato. Separate the coriander stalks from 3 the leaves. Finely chop the stalks and roughly chop the leaves. Set aside. 4 Thickly slice the red capsicum. Heat the olive oil in a frying pan over 5 medium heat. Add the onion, ginger, coriander 6 stalks and jerk seasoning. Cook until the onion has softened. Add the capsicum to the frying pan, 8 and cook until softened. Stir in the thyme, chopped tomatoes, vinegar, brown sugar 10 and stock. Simmer for a few minutes and then 11 add the sweet potato and simmer for 10-15 minutes more. Add the white rice to the boiling 17 salted water (about 11 mins). Stir in the beans and season with salt 25 and pepper. Estimated Number of Minutes 28 Drain the rice. Once the sweet potato is tender stir 29 through half of the coriander leaves. Distribute among serving bowls and 29.5 serve with the rice. 30 Garnish with remaining coriander.. -

Jamaican-Style Barbecue G

Jamaican jerk Jamaican-Style marinade is full of hot, spicy, and herbal ingredients, like Scotch bonnet Barbecue peppers, scallions, ginger, garlic, thyme, bay, cinnamon, Making and using hot and spicy “jerk” peppercorns, nutmeg, and allspice. BY JAY B. MCCARTHY rowing up in Jamaica, I learned to love the wood. In Jamaica, the wood—traditionally allspice Gisland food, especially the jerk—Jamaican (called pimento), but sometimes other woods— barbecue—we ate at roadside stands. that’s used to make the barbecue frame imparts half Despite its name, Jamaican jerk has no similari- the luscious depth of flavor to jerked meats. The ties to dried meat jerky. The name comes from the other half comes from the jerk marinade itself, which way the meat was “jerked” (turned) regularly to en- is made of herbs, spices, and Scotch bonnet peppers. sure even cooking. And, like barbecue, the term jerk When I began cooking in the United States, I refers to the seasoning, the finished product, and the explored ways to recreate the hot, spicy, herbal mix- cooking method. ture that haunted my palate. Now, as a chef, I regu- Jerked meat is cooked slowly over a fire of green larly incorporate jerk into my restaurant menu. The Photo: Sloan Howard. All other photos: Ruth Lively 42 FINE COOKING Copyright © 1994 - 2007 The Taunton Press jerk mixture is easy to make, and it can be used on many kinds of meat, poultry, and fish. If the tradi- tional method of roasting jerk over green wood doesn’t suit you, you can use any kind of grill setup, a smoker, or your oven. -

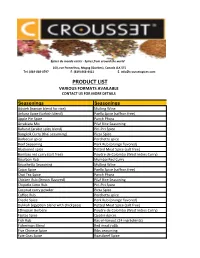

Product List Various Formats Available Contact Us for More Details

Épices du monde entier - Spices from around the world 160, rue Pomerleau, Magog (Quebec), Canada J1X 5T5 Tel. (819-868-0797 F. (819) 868-4411 E. [email protected] PRODUCT LIST VARIOUS FORMATS AVAILABLE CONTACT US FOR MORE DETAILS Seasonings Seasonings Advieh (iranian blend for rice) Mulling Wine Ankara Spice (turkish blend) Paella Spice (saffron free) Apple Pie Spice Panch Phora Arrabiata Mix Pilaf Rice Seasoning Baharat (arabic spicy blend) Piri-Piri Spice Bangkok Curry (thai seasoning) Pizza Spice Barbecue spice Porchetta spice Beef Seasoning Pork Rub (orange flavored) Blackened spice Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Bombay red curry (salt free) Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Bourbon Rub Mumbai Red Curry Bruschetta Seasoning Mulling Wine Cajun Spice Paella Spice (saffron free) Chai Tea Spice Panch Phora Chicken Rub (lemon flavored) Pilaf Rice Seasoning Chipotle-Lime Rub Piri-Piri Spice Coconut curry powder Pizza Spice Coffee Rub Porchetta spice Creole Spice Pork Rub (orange flavored) Dukkah (egyptian blend with chickpeas) Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Ethiopian Berbéré Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Fajitas Spice Quatre épices Fish Rub Ras-el-hanout (24 ingrédients) Fisherman Blend Red meat ru8b Five Chinese Spice Ribs seasoning Foie Gras Spice Roastbeef Spice Game Herb Salad Seasoning Game Spice Salmon Spice Garam masala Sap House Blend Garam masala balti Satay Spice Garam masala classic (whole spices) Scallop spice (pernod flavor) Garlic pepper Seafood seasoning Gingerbread Spice Seven Japanese Spice Greek Spice Seven -

WORLD FLAVORS Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago Disc 1: Recipes from In-Country Chefs and Presenters TABLE of CONTENTS

THE CULINARY INSTITUTE OF AMERICA IN ASSOCIATION WITH UNILEVER FOOD SOLUTIONS PRESENTS SAVORING THE BEST OF WORLD FLAVORS Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and tobago Disc 1: Recipes from In-Country Chefs and Presenters TABLE OF CONTENTS Ackee and Salt fish Mac and Cheese ............................................................................................... 3 Bakes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Festival Dumplings ............................................................................................................................ 5 Jerk Chicken Spring Rolls ................................................................................................................. 6 Tamarind Ginger Dipping Sauce ..................................................................................................... 7 Spicy Mango and Mint Dipping Sauce ........................................................................................... 8 Lemongrass and Coconut Dipping Sauce ...................................................................................... 9 Sweet and Sour Pickled Onions ..................................................................................................... 10 “Kokonda” Tuna and Coconut Ceviche ....................................................................................... 11 Coconut Mayonaise ........................................................................................................................