Saving New Sounds: Podcast Preservation and Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOTION to DISMISS V

1 HONORABLE BRIAN MCDONALD Department 48 2 Noted for Consideration: April 27, 2020 Without Oral Argument 3 4 5 6 7 IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF KING 8 WASHINGTON LEAGUE FOR INCREASED 9 TRANSPARENCY AND ETHICS, a NO. 20-2-07428-4 SEA Washington non-profit corporation, 10 Plaintiff, 11 FOX DEFENDANTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS v. 12 FOX NEWS, FOX NEWS GROUP, FOX 13 NEWS CORPORATION, RUPERT MURDOCH, AT&T TV, COMCAST, 14 Defendants. 15 16 INTRODUCTION & RELIEF REQUESTED 17 Plaintiff WASHLITE seeks a judicial gag order against Fox News for airing supposedly 18 “deceptive” commentary about the Coronavirus outbreak and our nation’s response to it. But the 19 only deception here is in the Complaint. Fox’s opinion hosts have never described the Coronavirus 20 as a “hoax” or a “conspiracy,” but instead used those terms to comment on efforts to exploit the 21 pandemic for political points. Regardless, the claims here are frivolous because the statements at 22 issue are core political speech on matters of public concern. The First Amendment does not permit 23 censoring this type of speech based on the theory that it is “false” or “outrageous.” Nor does the law 24 of the State of Washington. The Complaint therefore should be dismissed as a matter of law. 25 MOTION TO DISMISS - 1 LAW OFFICES HARRIGAN LEYH FARMER & THOMSEN LLP 999 THIRD AVENUE, SUITE 4400 SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98104 TEL (206) 623-1700 FAX (206) 623-8717 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS 2 The country has been gripped by an intense public debate about the novel Coronavirus 3 outbreak. -

IAB Podcast Ad Revenue Study, July 2020

U.S. Podcast Advertising Revenue Study Includes: • Detailed Industry Analysis • 2020 COVID-19 Impact & Growth Projections • 2021-2022 Growth Projections (Pre COVID-19) • Full Year 2019 Results July 2020 Prepared by PwC ABC Audio Midroll Media AdsWizz National Public Media AudioBoom Slate Authentic Spotify Sponsors DAX Vox Media Podcast Network The IAB would like to thank the following Entercom WarnerMedia sponsors for supporting this year’s study: Market Enginuity Westwood One Megaphone Wondery FY 2019 Podcast Ad Revenue Study, July 2020 2 IAB US Podcast Advertising Study is prepared by PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (“PwC”) on an ongoing basis, with results released annually. Initiated by the Interactive Advertising Bureau’s (IAB) Audio Industry Working Group in 2017, this study uses data and information reported directly to PwC from companies that generate revenue on podcast platforms. The results reported are considered to be a reasonable measurement of podcast advertising revenues because much of the data is compiled directly from the revenue generating About this Study companies. PwC does not audit the information and provides no opinion or other form of assurance with respect to the accuracy of the information collected or presented. Only aggregate results are published and individual company information is held with PwC. Further details regarding scope and methodology are provided in this report. FY 2019 Podcast Ad Revenue Study, July 2020 3 Contents Executive Summary 5 2020 Growth Projections & COVID-19 Impact on US 7 Podcast Advertising -

PRACHTER: Hi, I'm Richard Prachter from the Miami Herald

Bob Garfield, author of “The Chaos Scenario” (Stielstra Publishing) Appearance at Miami Book Fair International 2009 PACHTER: Hi, I’m Richard Pachter from the Miami Herald. I’m the Business Books Columnist for Business Monday. I’m going to introduce Chris and Bob. Christopher Kenneally responsible for organizing and hosting programs at Copyright Clearance Center. He’s an award-winning journalist and author of Massachusetts 101: A History of the State, from Red Coats to Red Sox. He’s reported on education, business, travel, culture and technology for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, the LA Times, the Independent of London and other publications. His articles on blogging, search engines and the impact of technology on writers have appeared in the Boston Business Journal, Washington Business Journal and Book Tech Magazine, among other publications. He’s also host and moderator of the series Beyond the Book, which his frequently broadcast on C- SPAN’s Book TV and on Book Television in Canada. And Chris tells me that this panel is going to be part of a podcast in the future. So we can look forward to that. To Chris’s left is Bob Garfield. After I reviewed Bob Garfield’s terrific book, And Now a Few Words From Me, in 2003, I received an e-mail from him that said, among other things, I want to have your child. This was an interesting offer, but I’m married with three kids, and Bob isn’t quite my type, though I appreciated the opportunity and his enthusiasm. After all, Bob Garfield is a living legend. -

Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: a Review and Framework

Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework Item Type Journal Article (On-line/Unpaginated) Authors Trant, Jennifer Citation Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework 2009-01, 10(1) Journal of Digital Information Journal Journal of Digital Information Download date 02/10/2021 03:25:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/105375 Trant, Jennifer (2009) Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework. Journal of Digital Information 10(1). Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework J. Trant, University of Toronto / Archives & Museum Informatics 158 Lee Ave, Toronto, ON Canada M4E 2P3 jtrant [at] archimuse.com Abstract This paper reviews research into social tagging and folksonomy (as reflected in about 180 sources published through December 2007). Methods of researching the contribution of social tagging and folksonomy are described, and outstanding research questions are presented. This is a new area of research, where theoretical perspectives and relevant research methods are only now being defined. This paper provides a framework for the study of folksonomy, tagging and social tagging systems. Three broad approaches are identified, focusing first, on the folksonomy itself (and the role of tags in indexing and retrieval); secondly, on tagging (and the behaviour of users); and thirdly, on the nature of social tagging systems (as socio-technical frameworks). Keywords: Social tagging, folksonomy, tagging, literature review, research review 1. Introduction User-generated keywords – tags – have been suggested as a lightweight way of enhancing descriptions of on-line information resources, and improving their access through broader indexing. “Social Tagging” refers to the practice of publicly labeling or categorizing resources in a shared, on-line environment. -

18 Lc 117 0073 H. R

18 LC 117 0073 House Resolution 950 By: Representatives Jones of the 53rd, Smyre of the 135th, Gardner of the 57th, Thomas of the 56th, Metze of the 55th, and others A RESOLUTION 1 Recognizing February 14, 2018, as Clark Atlanta University Day at the state capitol, and for 2 other purposes. 3 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University was established in 1988 upon the consolidation of its 4 two parent institutions Atlanta University, established in 1865, and Clark College, 5 established in 1869; and 6 WHEREAS, the university's four colleges offer 38 academic programs to roughly 4,000 7 students each year, making a valuable contribution to the future workforce and leadership of 8 Georgia; and 9 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of the Center for Cancer Research and 10 Therapeutic Development which thrives under the leadership of Georgia Research Alliance 11 Eminent Scholar Shafiq A. Khan, Ph.D., and, as such, is the only Historically Black Colleges 12 and Universities (HBCU) member of the Georgia Research Alliance in addition to being the 13 nation's largest academic prostate cancer research center; and as a result of its breakthrough 14 research, presently has five patents and patents pending; and 15 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of Jazz 91.9 FM-WCLK, an NPR affiliate, 16 and is Metro Atlanta community's only jazz radio station and this year celebrates 41 years 17 of service to the community; and 18 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of one of the nation's most prolific 19 undergraduate Mass Media Arts program, responsible for nurturing talent such as Sheldon 20 "Spike" Lee, Nnegest Likke, Jacque Reed, and Eva Marcille; and 21 WHEREAS, Clark Atlanta University is the home of the Center for Functional Nanoscale 22 Materials, the Center for Alternative Energy and Energy Conservation, the Center for 23 Biomedical and Bimolecular Research, and the Center for Cyberspace and Information H. -

‗DEFINED NOT by TIME, but by MOOD': FIRST-PERSON NARRATIVES of BIPOLAR DISORDER by CHRISTINE ANDREA MUERI Submitted in Parti

‗DEFINED NOT BY TIME, BUT BY MOOD‘: FIRST-PERSON NARRATIVES OF BIPOLAR DISORDER by CHRISTINE ANDREA MUERI Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Kimberly Emmons Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August 2011 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Andrea Mueri candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree *. (signed) Kimberly K. Emmons (chair of the committee) Kurt Koenigsberger Todd Oakley Jonathan Sadowsky May 20, 2011 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 I dedicate this dissertation to Isabelle, Genevieve, and Little Man for their encouragement, unconditional love, and constant companionship, without which none of this would have been achieved. To Angie, Levi, and my parents: some small piece of this belongs to you as well. 4 Table of Contents Dedication 3 List of tables 5 List of figures 6 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 8 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: The Bipolar Story 28 Chapter 3: The Lay of the Bipolar Land 64 Chapter 4: Containing the Chaos 103 Chapter 5: Incorporating Order 136 Chapter 6: Conclusion 173 Appendix 1 191 Works Cited 194 5 List of Tables 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Manic and Depressive Episodes 28 2. Therapeutic Approaches for Treating Bipolar Disorder 30 3. List of chapters from table of contents 134 6 List of Figures 1. Bipolar narratives published by year, 2000-2010 20 2. Graph from Gene Leboy, Bipolar Expeditions 132 7 Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge my advisor, Kimberly Emmons, for her ongoing guidance and infinite patience. -

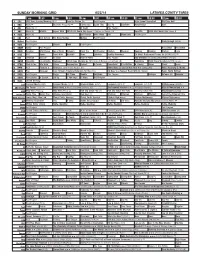

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

The Conspiracy Issue Pandemic Know-It-Alls 6

THE CONSPIRACY ISSUE PANDEMIC KNOW-IT-ALLS 6 FOURTEEN NEW CONSPIRACY THEORISTS 12 ARE YOU BEING GANG-STALKED? 14 EGOS, ICKE & COVID 16 THE PANDEMIC COOKBOOK 20 THE TALKING DOG CONSPI CY 24 GUENTER ZIMMERMANN 30 THERE IS NO CONSPIRACY 36 DISMANTLING THE 5G MYTH 38 TOP 20 RONA MYTHS 39 MICHAEL JORDANS RETIREMENT 43 STEVIE WONDER IS BLIND NOT 46 MOTIVATIONAL QUOTES FOR CONSPIRACY THEORISTS 50 ROBERT DE NIRO IS A MYTH 52 10 MYTHS ABOUT UNCIRCUMCISED DICKS 56 A PANDEMIC of would? If so, how far do we have points for being obese and el- to wreck the economy to achieve derly? this? To put it another way, how Know-it-Alls many bodies do we have to sac- Do you hoard money, or do you rifice to save the economy? stock up on supplies? If SARS-CoV-2 can actually trav- “We hear plenty about herd im- el in particles of air pollution like munity, but not nearly enough I heard last week, is a lockdown about herd stupidity.” ( ) meaningless, or should we just Should you wear rubber gloves avoid North Jersey? at the gas station, or does that hen it comes to this whole What’s the crude-case fatality make you a Germ Cuck? COVID-19 hall of mirrors rate? What’s the rate of con- Are businesses reopening too W and how we possibly find firmed cases v. suspected total soon to prevent more infections Are “they” all in cahoots, or are our way out if this creepy carni- infections? How many cases are or too late to save the economy? “they” too stupid to pull that off? val exhibit we’re trapped inside closed? How many are still open? hoping it’s not really a cheesy Are they counting people who Would a vaccine apply to every Is it true that the virus can be horror movie made flesh, it seems died outside of hospitals and mutation, or do they have to keep spread through flatulence? that everyone has an answer ex- were never tested for the virus? coming up with new vaccines? Or cept me. -

Genetics Was the Key Old Furniture, Tires, Mattresses and More Into the Scrubtown Sinkhole

A3 SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 4, 2018 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $2 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM SUNDAY + PLUS >> Tigers 1B Just what WHOLE we’ve been roll LOTTA waiting for over BULL 1D Opinion/4A Bolles TASTE BUDDIES See 6C COMMUNITY CLEANUP TOP BANANA MODERN VERSION OF THE FRUIT OWES ITS EXISTENCE TO THIS LAKE CITY MAN Photos by TONY BRITT/Lake City Reporter A volunteer drags a garbage can loaded with debris from the sinkhole on Scrubtown Road Saturday. Around 20 volunteers pitched in to help. SCRUBTOWN SCRUB DOWN Photos by CARL MCKINNEY/Lake City Reporter Furniture, mattresses, Nader Vakili holds up two hands of bananas, which are commonly misidentified more pulled from pit. as bunches. Vakili’s work as a plant geneticist-pathologist was used to breed modern bananas found in grocery stores. By TONY BRITT [email protected] FORT WHITE — For gen- erations people threw garbage, Genetics was the key old furniture, tires, mattresses and more into the Scrubtown sinkhole. Nader Vakili figured Saturday, around 20 volun- out how to breed a teers and members of various sterile ‘mutant’ plant. environmental groups gathered at the sinkhole to clean the By CARL MCKINNEY debris from the area. Less than [email protected] three hours in, they had nearly filled a 30-cubic-yard trash bin. A piece of Nader Vakili The group plans to return next is in the bananas sold in Saturday. grocery stores throughout “We’re holding a cleanup for the world. this sinkhole on Scrubtown Eric Wise struggles to keep his footing Vakili explained the Saturday. -

Baptist Church in Nursing - Education (BSN to MSN); and Valecia Baldwin, Girls Do Not Always Have the Get the Shovel and Conduct My Sumter

Woods in the hunt at 2 under B1 SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 FRIDAY, APRIL 12, 2019 75 CENTS Sumter Police arrest 6 in drug-related sting A2 School district waiting on state for next move Financial recovery plan had $6.6M in budget cuts, but state board turned it down BY BRUCE MILLS enue levels. Because the state board de- its intention is to achieve necessary per- mean the state can take over the entire [email protected] nied the district’s appeal of state Super- sonnel cuts through attrition and re- district or take board members off their intendent of Education Molly Spear- structuring. seats, but it does allow them to lead the Though it will change because Sum- man’s fiscal emergency declaration in “I don’t know where the plan stands district financially. ter School District’s appeal of its state- Sumter, the state will recommend now, since we lost the appeal,” Miller In an email to all district employees declared fiscal emergency was denied changes to the plan and budget. said. “I’m waiting to hear from the state late Wednesday afternoon, Interim Su- Tuesday, the financial recovery plan District Chief Financial Officer Jenni- Department. I am not allowed to move perintendent Debbie Hamm also said presented at the hearing showed about fer Miller said Thursday that she and forward with anything, and we’re on administration is waiting on guidance $6.6 million in budget cuts.The cuts pre- administration are on hold now, waiting hold until the state Department con- from the state Department and doesn’t sented before the state Board of Educa- on those recommendations from the tacts us because they are technically in want to cut personnel. -

Podcasts in MENA • Soti 2020

Podcasts in MENA State of the Industry 2020 State of the Industry 2020 2 of 22 TABLE OF CONTENTS From the CEO’s Desk .............................................................................................................3 Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................4 The Year That Was .................................................................................................................5 Changing Habits ............................................................................................................................................7 Creators Adapt ..............................................................................................................................................8 Brands in Podcasts .......................................................................................................................................9 Monetisation ..................................................................................................................................................11 An Exclusive World ......................................................................................................................................12 Standardisation ...................................................................................................................16 The Podcast Index .......................................................................................................................................17 -

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg Shiny little platters. Not even five inches across. How could they possibly contain the soundtrack of four decades? How could the phone calls, the encounters, the danger, the desperation, the exhilaration and big, big laughs from two score years be compressed onto a handful of CDs? If you’ve lived with NPR, as so many of us have for so many years, you’ll be astonished at how many of these reports and conversations and reveries you remember—or how many come back to you (like familiar songs) after hearing just a few seconds of sound. And you’ll be amazed by how much you’ve missed—loyal as you are, you were too busy that day, or too distracted, or out of town, or giving birth (guess that falls under the “too distracted” category). Many of you have integrated NPR into your daily lives; you feel personally connected with it. NPR has gotten you through some fairly dramatic moments. Not just important historical events, but personal moments as well. I’ve been told that a woman’s terror during a CAT scan was tamed by the voice of Ira Flatow on Science Friday being piped into the dreaded scanner tube. So much of life is here. War, from the horrors of Vietnam to the brutalities that evanescent medium—they came to life, then disappeared. Now, of Iraq. Politics, from the intrigue of Watergate to the drama of the Anita on these CDs, all the extraordinary people and places and sounds Hill-Clarence Thomas controversy.