Offprinted from MODERN LANGUAGE REVIEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entre Classicismo E Romantismo. Ensaios De Cultura E Literatura

Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism is an academic series published on- line by the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS) and hosted by the central library of the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Portugal. Studies in Classicism and Romanticism has come into being as a result of the commitment of a group of scholars who are especially interested in English literature and culture from the mid-seventeenth to the mid- nineteenth century. The principal objective of the series is the publication in electronic format of monographs and collections of essays, either in English or in Portuguese, with no pre-established methodological framework, as well as the publication of relevant primary texts from the period c. 1650–c. 1850. Series Editors Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Editorial 2 Sumário Apresentação 4 Maria Luísa Malato Borralho, “Metamorfoses do Soneto: Do «Classicismo» ao «Romantismo»” 5 Adelaide Meira Serras, “Science as the Enlightened Route to Paradise?” 29 Paula Rama-da-Silva, “Hogarth and the Role of Engraving in Eighteenth-Century London” 41 Patrícia Rodrigues, “The Importance of Study for Women and by Women: Hannah More’s Defence of Female Education as the Path to their Patriotic Contribution” 56 Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa, “Sugestões Portuguesas no Romantismo Inglês” 65 Maria Zulmira Castanheira, “O Papel Mediador da Imprensa Periódica na Divulgação da Cultura Britânica em Portugal ao Tempo do Romantismo (1836-1865): Matérias e Imagens” 76 João Paulo Ascenso P. -

Ossian's Folk Psychology

Ossian’s FOLK PSYCHOLOGY BY JOHN SAVARESE This essay takes James Macpherson’s Ossian poems as a case study in how early Romantic poetics engaged the sciences of the embodied mind and set the terms that would continue to drive discussions of poetry’s origin and functions well into the nineteenth century. When Macpherson turned to the popular literature of ancient Scotland, I argue, he found in it what philosophers now call a “folk psychology”: a commonsense understanding of how other minds work. Ordinary non-philosophers generally think that other people’s behavior is best explained by referring to mental states, which can be described using concepts like belief, desire, and intention: he raises the glass because he wants to take a sip; Elizabeth refuses Mr. Darcy’s proposal because she believes he is an unjust and ungenerous man and wants nothing to do with him.1 Most philosophers who identify a pre-reflective folk psychology of this kind grant that it is a dependable strategy for explaining human behavior—even if they think that the language of mental states is a vulgar illusion that will ultimately evaporate into the more nuanced language of a mature science. In his Fragments of Ancient Poetry (1760), Macpherson uses ostensibly ancient poems to explore such pre-philosophical or naïve theories about the mind.2 The first section of this essay frames the Ossianic project as an intervention in what were then current theories of ancient poetry, theories which made the ancient text the site of information about the primitive mind. The Ossian poems purported to survey philosophically impoverished models of mental life; yet, as the second section demonstrates, they also became a source of information about even contemporary people’s most basic mental architecture. -

Staying Optimistic: the Trials and Tribulations of Leibnizian Optimism

Strickland, Lloyd 2019 Staying Optimistic: The Trials and Tribulations of Leibnizian Optimism. Journal of Modern Philosophy, 1(1): 3, pp. 1–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.32881/jomp.3 RESEARCH Staying Optimistic: The Trials and Tribulations of Leibnizian Optimism Lloyd Strickland Manchester Metropolitan University, GB [email protected] The oft-told story of Leibniz’s doctrine of the best world, or optimism, is that it enjoyed a great deal of popularity in the eighteenth century until the massive earthquake that struck Lisbon on 1 November 1755 destroyed its support. Despite its long history, this story is nothing more than a commentators’ fiction that has become accepted wisdom not through sheer weight of evidence but through sheer frequency of repetition. In this paper we shall examine the reception of Leibniz’s doctrine of the best world in the eighteenth century in order to get a clearer understanding of what its fate really was. As we shall see, while Leibniz’s doctrine did win a good number of adherents in the 1720s and 1730s, especially in Germany, support for it had largely dried up by the mid-1740s; moreover, while opponents of Leibniz’s doctrine were few and far between in the 1710s and 1720s, they became increasing vocal in the 1730s and afterwards, between them producing an array of objections that served to make Leibnizian optimism both philosophically and theologically toxic years before the Lisbon earthquake struck. Keywords: Leibniz; Optimism; Best world; Lisbon earthquake; Evil; Wolff The oft-told story of Leibniz’s doctrine of the best world, or optimism, is that it enjoyed a great deal of popularity in the eighteenth century until the massive earthquake that struck Lisbon on 1 November 1755 destroyed its support. -

Charlotte Smith, William Cowper, and William Blake: Some New Documents

ARTICLE Charlotte Smith, William Cowper, and William Blake: Some New Documents James King Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 13, Issue 2, Fall 1979, pp. 100-101 100 CHARLOTTE SMITH, WILLIAM COWPER, AND WILLIAM BLAKE: SOME NEW DOCUMENTS JAMES KING lthough her reputation is somewhat diminished Rose, of 25 April 1806 (Huntington)." As before, now, Charlotte Smith was the most celebrated Mrs. Smith is complaining about Hayley's neglect of A novelist in England in the early 1790s. Like her. George Romney, John Flaxman, William Cowper, and William Blake, Mrs. Smith was one of a number of I lose a great part of the regret I might writers and painters assisted by William Hayley in otherwise feel in recollecting, that a various ways. Mrs. Smith met Cowper at Eartham in mind so indiscriminating, who is now 1792, and the events of that friendship have been seized with a rage for a crooked figure= chronicled.1 Mrs. Smith never met William Blake, and maker & now for an engraver of Ballad only one excerpt from a letter linking them has pictures (the young Mans tragedy; & the previously been published. In this note, I should jolly Sailers Farewell to his true love Sally) —I dont mean the Hayleyan like to provide some additional information on Mrs. 5 Smith and Cowper, but I shall as well cite three collection of pretty ballads) —Such a unpublished excerpts from her correspondence in mind, can never be really attached; or which she comments on Blake. is the attachment it can feel worth having — In an article of 1952, Alan Dugald McKillop provided a n excellent account of Charlotte Smith's The "crooked figure=maker" is probably a reference letters.2 In the course of that essay, McKilloD to Flaxman and his hunch-back; despite the notes a facetiou s and denigrating remark of 20 March disclaimer, the engraver is more than likely to be 1806 (Hunt ington) about Hayley's Designs to a Series Blake. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

The Gentleman's Magazine; Or Speakers’ Corner 105

Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen______ Literaturwissenschaft Herausgegeben von Reinhold Viehoff (Halle/Saale) Gebhard Rusch (Siegen) Rien T. Segers (Groningen) Jg. 19 (2000), Heft 1 Peter Lang Europäischer Verlag der Wissenschaften SPIEL Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen Literaturwissenschaft SPIEL: Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen Literaturwissenschaft Jg. 19 (2000), Heft 1 Peter Lang Frankfurt am Main • Berlin • Bern • Bruxelles • New York • Oxford • Wien Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Siegener Periodicum zur internationalen empirischen Literatur wissenschaft (SPIEL) Frankfurt am Main ; Berlin ; Bern ; New York ; Paris ; Wien : Lang ISSN 2199-80780722-7833 Erscheint jährl. zweimal JG. 1, H. 1 (1982) - [Erscheint: Oktober 1982] NE: SPIEL ISSNISSN 2199-80780722-7833 © Peter Lang GmbH Europäischer Verlag der Wissenschaften Frankfurt am Main 2001 Alle Rechte Vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen Literaturwissenschaft SPECIAL ISSUE / SONDERHEFT SPIEL 19 (2000), H. 1 Historical Readers and Historical Reading Historische Leser und historisches Lesen ed. by / hrsg. von Margaret Beetham (Manchester) & -

Dictynna, 14 | 2017 ‘Pastoral and Its Futures: Reading Like (A) Mantuan’ 2

Dictynna Revue de poétique latine 14 | 2017 Varia ‘Pastoral and its futures: reading like (a) Mantuan’ Stephen Hinds Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/dictynna/1443 DOI: 10.4000/dictynna.1443 ISSN: 1765-3142 Electronic reference Stephen Hinds, « ‘Pastoral and its futures: reading like (a) Mantuan’ », Dictynna [Online], 14 | 2017, Online since 21 November 2017, connection on 10 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/dictynna/1443 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/dictynna.1443 This text was automatically generated on 10 September 2020. Les contenus des la revue Dictynna sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. ‘Pastoral and its futures: reading like (a) Mantuan’ 1 ‘Pastoral and its futures: reading like (a) Mantuan’ Stephen Hinds BAPTISTA MANTUANUS (1447-1516): THE ADULESCENTIA 1 This paper offers some glimpses of a particular moment in early modern pastoral tradition, with two purposes: first, to map the self-awareness of one post-Virgilian poet’s interventions in pastoral tradition, an episode of literary historical reflexivity which I offer, as such, to Alain Deremetz, author of Le miroir des muses;1 but also, as a second methodological emphasis, to dramatize the spacious reach of Virgilian pastoral when it is viewed in the future tense, through the history of its early modern reception, and to suggest that that spaciousness is inseparable from the idea of ‘Virgil’ for an interpreter of -

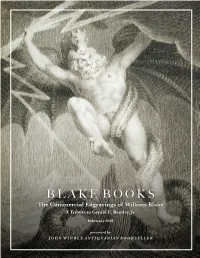

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles. -

The Lusiad of Luis De Camoens, Closely Translated. with a Portrait

I LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. I m ti UXITED STATES OF AMEKICA.| ." r ., ; fear, les$ iapi^y thaTLxenoYniBd (2_.CX/\AAJ^<vi^ ^ V>-U^ cbu THE LUSIAD OP LUIS DE CAMOENS, CLOSELY TRANSLATED. WITH A PORTRAIT OF THE POET, A COMPENDIUM OF HIS LIFE, AN INDEX TO THE PRINCIPAL PASSAGES OP HIS POEM, A VIEW OF THE " FOUNTAIN OF TEARS,' AND MARGINAL AND ANNEXED NOTES, ORIGINAL AND SELECT. BY Lt.-COLl. SIE T. LIVINGSTON MITCHELL, Kt. D.C.L. LONDON : T. k W. BOONE, NEW BOND STREET. 1854. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THOMAS EARL OF DUNDONALD, G.C.B. YICE ADiriEAL OE THE BLUE, GRAND CROSS OF THE IMPERIAL BRAZILIAN ORDER OF THE CRUZERO; KNIGHT OF THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE SAVIOUR OF GRIiECE; AND OF THE ORDER OF MERIT OF CHILI, &C. &C. &C. IS DEDICATED, WITH MUCH EESPECT, BY HIS LOEDSHIP'S OBLIGED HUMBLE SEEVAIS'T, T LIVINGSTON MITCHELL. PREFACE. This translation is submitted to tlie public, as conveying- the Poet's meaning in tlie order of the versification, an undertaking of more difficulty in English, the terminations alone of verbs sufficing for good rhyme in Portuguese. In quantity the original varies as to the number of syllables—and in attempting an imitation in a different language—the employment of nearly as many cannot, he trusts, be objected to. Prom ten to twelve or even fourteen syllables occur in one line of the original, and thus, although ten syllables is the usual quantity in Ottava Rima when imitated in English—more has been required in translating here the lines of the Lusiad. -

V.S. Lectures, No. 78 the TENTH ECLOGUE a Lecture Delivered to the Virgil Society 22Nd October 1966 by C.G

V.S. Lectures, No. 78 THE TENTH ECLOGUE A lecture delivered to the Virgil Society 22nd October 1966 by C.G. Hardie, M.A. The Eclogues of Virgil are among the most puzzling poems that have come down to us from the ancient world. The Tenth is no easier to understand than the Fourth or the Sixth, and it has attracted much, though less special attention than, for instance, the linked problems of the First and Ninth, At a meeting of this Society, nine years ago, on the 19th October 1957, I spoke about the Fourth Eclogue (Lecture Summary No. 42) and six years ago, on 22nd October 1960, on the Sixth Eclogue (No. 50). I must begin today by making a rather different point about the Fourth Eclogue than I made then, and then proceed to say briefly much the same about the Sixth, repeating myself somewhat because Gallus in the Tenth cannot be understood without some theory of what Gallus means in the Sixth. The importance of the Fourth Eclogue in Virgil's development lies, in my opinion, in that the poet of the humble pastoral, the imitator of the Alexandrian school, the ’neoteric1 follower of Callimachus and Catullus, one of the 'cantores Euphorionis1" for the first time, in a moment of intense enthusiasm, conceived of himself as one day in the future called to be the Roman Homer. The climax of the Fourth Eclogue is not the growing up, the accession and the triumph of the child in unifying and pacifying the world, but the thought that Virgil will be the poet of this divine life and victory. -

William Collins - Poems

Classic Poetry Series William Collins - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive William Collins(1721 - 1759) William Collins was born at Chichester and was educated at Winchester College and at Magdalen College, Oxford. His Persian Eclogues (1742) were published anonymously when he was seventeen. Coming up to London from Oxford he tried to establish himself as an author. He published Odes on Several Descriptive and Allegorical Subjects (1746) with his friend Joseph Warton whilst in London. The volume did not do well, and when his father died in 1744, Collins was left in debt and without a job. He got to know Dr Johnson who arranged an advance for him to write a translation of Aristotle's Poetics. However, when an uncle died leaving him £2000, Collins abandoned the project and paid his debts. After this he travelled for a while, but fits of depression became more serious and debilitating. He broke down completely on a journey in France in 1750, and died insane at the age of 38 in his sister's house in Chichester. The poet Thomas Gray commented favourably on Collins's work, and as the century progressed, he gained in reputation. Some of his finest odes as said to be 'Ode to Evening' and 'Dirge in Cymbeline'. His last know poem is Ode on the Popular Superstitions of the Highlands , written in 1749. His sister destroyed his manuscripts after his death. The Complete Works are edited by Richard Wendorf and Charles Ryskamp for the Oxford English Texts Series (1978). www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 In The Downhill Of Life In the downhill of life, when I find I'm declining, May my lot no less fortunate be Than a snug elbow-chair can afford for reclining, And a cot that o'erlooks the wide sea; With an ambling pad-pony to pace o'er the lawn, While I carol away idle sorrow, And blithe as the lark that each day hails the dawn Look forward with hope for tomorrow. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.