EBHR 24/25 Entities of the Same “Caste” in a Regional Scale of Similar Theistic Polities Embedded in Foreign Imperial Formations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virbhadra Singh Announces College and Gas Agency for Tikkar in Rohru Tehsil by : INVC Team Published on : 3 Jul, 2015 12:35 PM IST

Virbhadra Singh announces college and gas agency for Tikkar in Rohru tehsil By : INVC Team Published On : 3 Jul, 2015 12:35 PM IST INVC NEWS Shimla, Chief Minister Virbhadra Singh today announced opening of a degree college at Tikkar in Nawar valley of Rohru tehsil in Shimla district which would be made functional from next academic session. The Chief Minister also announced opening of a gas agency at Tikkar. He made these announcements while addressing a public meeting at Tikkar. He said he was personally going to monitor the progress of Theog-Hatkoti-Rohru road and for the very reason he would travel back to Shimla by road on Saturday. He assured undertaking repair and renovation of links roads in the area and directed for earlier completion of roads under construction. Shri Virbhadra Singh exhorted people to encourage their children for taking admissions in colleges being opened in rural areas and not to run towards the cities on the pretext of better education there. The Chief Minister said he was happy and satisfied to serve the people of the state for the last over thirty years and it was there love, trust and affection that he was able to serve the state as Chief Minister for sixth time. Shri Virbhadra Singh said since the formation of the state, the successive Congress governments worked with commitment for development and welfare of the people. Today, all the villages had been connected by roads and there were more than 34500 kms road network in the state. There were more than 15000 schools in the government sector in the state and in health sector, the state was marching ahead by providing quality health services to the people of the state, he added. -

Pneumonic Plague, Northern India, 2002

LETTERS compare the results of seroepidemio- Pneumonic Plague, and hemoptysis. A total of 16 cases logic investigations among cats living were reported from 3 hospitals in the in sites contaminated by avian viruses. Northern India, area: a local civil hospital, the state 2002 medical college, and a regional terti- This work was supported by the ary care hospital. Clinical material University of Milan grant F.I.R.S.T. To the Editor: A small outbreak collected from the case-patients and of primary pneumonic plague took their contacts was initially processed Saverio Paltrinieri,* place in the Shimla District of in the laboratories of these hospitals. Valentina Spagnolo,* Himachal Pradesh State in northern Wayson staining provided immediate Alessia Giordano,* India during February 2002. Sixteen presumptive diagnosis, and confirma- Ana Moreno Martin,† cases of plague were reported with a tory tests were performed at NICD. and Andrea Luppi† case-fatality rate of 25% (4/16). The Diagnosis of plague was confirmed infection was confirmed to the molec- *University of Milan, Milan, Italy; and for 10 (63%) of 16 patients (1). †Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della ular level with PCR and gene NICD conducted the following Lombardia e dell’Emilia, Brescia, Italy sequencing (1). A previous outbreak laboratory tests on 2 suspected culture in this region during 1983 was sug- References isolates, 2 sputum specimens, 1 lung gestive of pneumonic plague (22 autopsy material specimen, and 1 lung 1. Hopp M. Germany: H5N1 in domestic cats. cases, 17 deaths) but was not con- lavage sample (Table): 1) direct fluo- ProMed. 2006 Mar 1. [cited 2006 Mar 1]. -

Environmental Impact Assessment (Eia)

“REHABILITATION AND UPGRADATION TO INTERMEDIATE LANE OF PAONTA SAHIB RAJBAN SHILLAI MEENUS HATKOTI ROAD PORTION BETWEEN KM 97+000 TO 106+120 (GUMMA TO FEDIZ)( DESIGN RD 94+900 TO 103+550) OF NH 707 IN THE STATE OF HIMACHAL PRADESH” ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) Submitted To: Executive Engineer, NH Division, HPPWD Nahan. Submitted By: Consulting Engineering Associates S.C.O. 51, 2nd Floor, Swastik Vihar Mansa Devi Road, Sector-5, Panchkula Tel: 0172-2555529, Cell: 099145-75200 E-mail: [email protected] Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for Rehabilitation and Up-gradation to Intermediate lane of Paonta Sahib Rajban Shillai Meenus Hatkoti road portion between Km 97+000 to 106+120 (Gumma to Fediz)( Design RD 94+900 to 103+550) of NH 707 in the state of Himachal Pradesh 1 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 9 1.1.1 General ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.1.2 Importance of Project ......................................................................................................... 9 1.2 THE STUDY METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................. 12 1.2.1 Environmental Assessment .............................................................................................. -

Date – 20-11-2019 Communication Plan

Communication Plan- 2019 DATE – 20-11-2019 COMMUNICATION PLAN DDMA SHIMLA TOLL FREE NO:- 1077 CONTACT NO:- 0177-2800880, 2800881 2800882 2800883 FAX NO:-0177-2805881 EMAIL ID:[email protected] District Disaster Management Authority, Shimla. 1 Communication Plan- 2019 Important Telephone Numbers ADMINISTRATIVE SETUP OF DISTRICT SHIMLA Sr. No Name &Designation Office Mobile Email id Number 1. Sh. Amit Kashyap 0177 -2655988 94185 -00005 dc -shi [email protected] Deputy Commissioner Fax No. Shimla 01772653535 2. Sh.Apoorv Devgan 0177-2657003 70806-00113 [email protected] A.D.C Shimla 3. Smt. Prabha Rajeev 0177-2657005 94185-55998 [email protected] ADM(L&O) 4. Vacant 0177 -2653436 admp -shi [email protected] ADM(P) 5. Sm. Neeraj Chandla 0177-2657007 94187-85085 [email protected] SDM Shimla (Urban) 6. Sh. Neeraj Gupta 0177-2657009 94181-81160 [email protected] SDM Shimla (Rural) 2651202(SDK) 7. Sh.Krishan Kumar 01783-238502 70180-21809 [email protected] Sharma SDM, Theog 8. Sh. Narender Chauhan 01782-233002 94598-78383 [email protected] SDM, Rampur 9. Sh. Babu Ram Sharma 01781-240009 94180-69810 [email protected] SDM, Rohru 10. Sh. Anil Chauhan 01783-260014 98160-34378 [email protected] SDM, Chopal 11. Sh. Ratti Ram 01781-272001 94181-17674 [email protected] SDM, Dodrakawar 94185-32233 12. Smt. Chetna Khadwal 01782 -240033 94184 -56920 sdmkum [email protected] SDM Kumharsain 01782-241111 13. Sh. Chandan Kapoor 0177-2657011 94180-56629 [email protected] AC to DC Shimla 14. -

Woodcarvings from Pabbar Valley

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 4(4), October 2005, pp. 380-385 Woodcarvings from Pabbar Valley Hari Chauhan Himachal State Museum, Shimla 171004, Himachal Pradesh Received 15 October 2004, revised 22 February 2005 Woodcarving was the favoured medium of artistic expression of the Indian subcontinent. Indian houses and temples were profusely adorned with it and are often inseparable from it. Woodcarving, an indigenous tradition craft finds a mention in the ancient texts such as the Rig Veda and Matsya Purana. Woodcarving craft was well developed in many states spe- cially, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Kerala, Kashmir and Madhya Pradesh. They differed in terms of the kind of wood and the craft tradition. In the early days of kings and nawabs, woodcarving was essentially seen as an adjunct to architecture. Palaces, havelis and temples were decorated with incredibly carved doors, windows and jalis (lattice work). The present paper describes traditional woodcarving work adoring houses and temples of Pabbar valley of Himachal Pradesh. Keywords: Woodcarving, Traditional Craft, Pabbar Valley, Himachal Pradesh IPC Int. Cl.7: B44C1/22, B44C5/04 The woodcarving, an indigenous craft tradition has worked windows made up of pieces of wood. In Ben- retained its economic and cultural importance for gal, the clay houses have large wooden pillars and hundreds of years. Wood was one of the most impor- beams with intricate carvings. Assam has a rich tradi- tant materials used in arts to express thoughts. Wood tion of wood works. Their places of worship included was used to carve various items for household use as large carvings of mythical figures. -

Compliance Status Report of Environment and Social Safeguards

Co m plia nc e S ta t us Re po rt o f Enviro nm e nt a nd S o c ia l S a fe g ua rds Report No.:- 05 Period: - Six month ending (30-06-2011) ENVIRONMENT SAFEGUARDING AND M ANAGEMENT REPORTING List of abbreviations and colloquial terms used ADB Asian Development Bank AY Academic Year Bigha Unit for measuring land (One Bigha = about 752 sq mtr) Biswa Unit for measuring land (One Biswa = about 40 sq mtr) CA Compensatory Afforestation CAMPA Compensatory Afforestation Management and Planning Agency CAT Catchment Area Treatment CBO Community Based Organization CES Chief Environment Specialist CMO Chief Medical Officer CSR Corporate Social Responsibility DC Deputy Commissioner DFO Divisional Forest Officer DGM Deputy General Manager distt. District DPR Detailed Project Report ECR Environment Compliance Report EIA Environment Impact Assessment EMP Environment Management Plan FRL Full Reservoir Level GoHP Government of Himachal Pradesh GoI Government of India HCC Hindustan Construction Company (Ltd) HDPE High-Density Poly-Ethylene HEP Hydro-Electric Project HFL Highest Flood Level HoP Head of Project HP Himachal Pradesh HPCEDIP Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Development Investment Programme HPFD Himachal Pradesh Forest Department HPPCL Himachal Pradesh Power Corporation Limited HPPWD Himachal Pradesh Public Works Department HPSEB Himachal Pradesh State Electricity Board HPSFDC Himachal Pradesh State Forest Development Corporation ITI Industrial Training Institute LADA Local Area Development Agency LADC Local Area Development Committee LADF Local -

Success Story

SUCCESS STORY Name of Trainee Beena Father Name Mr. Hari Kumar Village Shoba Tehsil Jubbal District Shimla State Himachal Pradesh Passed Out NSIC-Training Centre, 2015-16 (125 Hours) Family Background Miss Beena was born in Shoba, Jubbal. Her father is working as a farmer. After completing her 8th from Govt School, she joined NSIC Training center and successfully passed the ESDP conducted by MSME course of Fashion Designing. Present Status After receiving her certificate from MSME, she has started work from home and now she is earning approximately 3000 per Month to be financially independent. SUCCESS STORY Name of Trainee Rupa Father Name Mr. Ganesh Bahadur Village Battar Galu Tehsil Jubbal District Shimla State Himachal Pradesh Passed Out NSIC-Training Centre, 2015-16 (125 Hours) Family Background Miss Rupa was born in Battar Galu, Jubbal. Her father is working as a farmer. After completing her 8th from Govt School, she joined NSIC Training center and successfully passed the ESDP conducted by MSME course of Fashion Designing. Present Status After receiving her certificate from MSME, she has started work from home and now she is earning approximately 3000 per Month to be financially independent. SUCCESS STORY Name of Trainee Manju Father Name Mr. Satiman Village Badhal Tehsil Jubbal District Shimla State Himachal Pradesh Passed Out NSIC-Training Centre, 2015-16 (125 Hours) Family Background Miss Manju was born in Badhal, Jubbal. Her father is working as a farmer. After completing her 10th from Govt. School, she joined NSIC Training center and successfully passed the ESDP conducted by MSME course of Fashion Designing. -

SINGLE LINE DIAGRAM of 33/11 Kv SUB-STATION

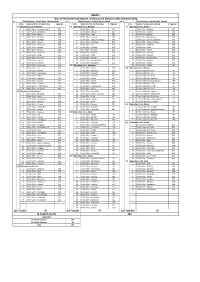

INDEX-I SLDs of 33 kV/22kV Sub-Stations of various Sub-Stations under Operation Wing (I) Chief Engineer, North Zone, Dharamshala (II) Chief Engineer, Central Zone, Mandi (III) Chief Engineer, South Zone, Shimla S.NO. Name of S.Stn./Control Point Page No. S.No. Name of S.Stn./Control Point Page No. S.No. Name of S.Stn./Control Point Page No. (i) Operation Circle, Dalhousie(i) Operation Circle, Bilaspur (i) Operation Circle, Nahan 1 33 kV S/Stn., Attare(Gangath) A01 1 33 kV S/Stn., Beri D01 1 33 kV S/Stn., Bagthan H01 2 33 kV S/Stn., Badukhar A02 2 33 kV S/Stn., Bharari D02 2 33 kV S/Stn., Charna H02 3 33 kV S/Stn., Bakloh A03 3 33 kV S/Stn., Jabli D03 3 33 kV S/Stn.,Dadahu H03 4 33 kV S/Stn., Chamba A04 4 33 kV S/Stn., Jhabola D04 4 33 kV S/Stn., Dhaulakuan H04 5 33 kV S/Stn., Channed A05 5 33 kV S/Stn., JNL Coll. S/Nagar D05 5 33 kV S/Stn., Dosarka/Badripur H05 6 33 kV S/Stn., Chowri A06 6 33 kV S/Stn., Kandrour D06 6 33 kV S/Stn., Dosarka/Nahan H06 7 33 kV S/Stn., Dalhousie A07 7 33 kV S/Stn., Kot D07 7 33 kV S/Stn., KalaAmb H07 8 33 kV S/Stn., Damtal A08 8 33 kV S/Stn., Namhol D08 8 33 kV S/Stn., Kheri H08 9 33 kV S/Stn., Dentha A09 9 33 kV S/Stn., Naswal D09 9 33 kV S/Stn., Palhori H09 10 33 kV S/Stn., Dharwala A10 10 33 kV S/Stn., Pangna D10 10 33 kV S/Stn., Puruwala H10 11 33 kV S/Stn., Dinka A11 11 33 kV S/Stn., Ratti D11 11 33 kV S/Stn., Rajgarh H11 12 33 kV S/Stn., Fatehpur A12 12 33 kV S/Stn., Slapper D12 12 33 kV S/Stn., Rampurghat H12 13 33 kV S/Stn., Garola A13 13 33 kV S/Stn., Sundernagar D13 13 33 kV S/Stn., Sarahan H13 -

43464-023: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy

Social Monitoring Report Project Number: 43464-023 May 2019 Period: July 2018 – December 2018 IND: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Transmission Investment Program - Tranche 1 Submitted by Himachal Pradesh Power Transmission Corporation Limited (HPPTCL) This social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. July 2018 to December 2018 Social Monitoring Report HIMACHAL PRADESH POWER TRANSMISSION CORPORATION LTD. (A STATE GOVERNMENT UNDERTAKING) Semi-Annual Social Monitoring Report Loan: 2794-IND May, 2019 IND: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Transmission Investment Program (Tranche 1) Reporting Period: July 2018 to December 2018 Prepared by: Himachal Pradesh Power Transmission Corporation Ltd (A State Government Undertaking) for Asian Development Bank. Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Project Description .................................................................................. 1 2. Purpose of the Report ......................................................................................................... 3 3. Social Safeguards Categorization ...................................................................................... -

Sawra-Kuddu Hydroelectric Project, Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy

Social Monitoring Report Project Number: 41627 May 2010 IND: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Development Investment Program Report for Sawra Kuddu Hydroelectric Project - Prepared by Himachal Pradesh Power Corporation Limited (HPPCL) This report has been submitted to ADB by the Himachal Pradesh Power Corporation Limited (HPPCL) and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Compliance Status Report of Environment and Social Safeguards ENVIRONMENT SAFEGUARDING AND MANAGEMENT REPORTING List of abbreviations and colloquial terms used ADB Asian Development Bank AY Academic Year Bigha Unit for measuring land (One Bigha = about 752 sq mtr) Biswa Unit for measuring land (One Biswa = about 40 sq mtr) CA Compensatory Afforestation CAMPA Compensatory Afforestation Management and Planning Agency CAT Catchment Area Treatment CBO Community Based Organization CES Chief Environment Specialist CMO Chief Medical Officer CSR Corporate Social Responsibility DC Deputy Commissioner DFO Divisional Forest Officer DGM Deputy General Manager distt. District DPR Detailed Project Report ECR Environment Compliance Report EIA Environment Impact Assessment EMP Environment Management Plan FRL Full Reservoir Level GoHP Government of Himachal Pradesh GoI Government of India HCC Hindustan Construction Company (Ltd) HDPE High-Density Poly-Ethylene HEP Hydro-Electric Project HFL Highest Flood Level HoP Head of Project HP Himachal Pradesh HPCEDIP Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Development -

GREENKO HATKOTI ENERGY PVT. LTD. Ffirwwmm,W

GREENKOHATKOTI ENERGYPVT. LTD. GorporateOffice: Plot no.1071, Road no.44, Jubil-ee Hills, Hyderabad - 500 033,INDIA ffirwwmM,w Ph:+ 91(40)4030100 E - Mail:[email protected] GHEPL/FCA/L6-Tu- s( Date01.08.2017 To, DivisionalForest Officer RohruForest Division, Rohru,Distt Shimla, HimachalPradesh. Sub:Diversion of 0.6943ha of additionalforest land for the constructionof 24 MW PauditalLassa HEP in favor of M/s Greenko Hatkoti Pvt. Ltd-Compliancereport against in-principalClearance (Stage-l)clearance received. Ref: i. Your'officeletter No.2709 Dated: 24/05/20L7. ii. Nodalofficer letter No. 48-2152/2010dated 26-05-2017. iii.RMoEF, Dehradun letter no. 8B/H. P. B/Otl 69 /20t6/294 dated: 24/ 05 / 2Or7. DearSir, With referenceto the above-mentionedsubject, here with attachedpoint wise complianceto the conditionsmentioned in-principal clearance as Annexure-1.we also confirm you that, we have paid/depositan amountof Rs5,34,390.85 against Compensatory A forestation(C.A, Rs-46,737.96) and Net PresentValue[NPV, Rs- 4,85-,316)through NEFT UTR NO: SB|N41720893520L, dated 27-Jul20t7.in CAMPAaccount by Challahgenerate by OnlinePortal Method. We requestyou to kindlyforward the sameto Nodalofficer for hisnecessary action please. Thankingyou YoursFaithfully, For Authori Shimlaoffice: 2nofloor, Plot no.B-2, Lane 4, Sector2, New Shimla,Shimla district, Himachal Pradesh - 171009 Siteoffice: zndfloor, Padam House, Samala, Rohru, Shimla District, H.P. GREENK HATKOTIENERGY PvT' LTD. ffifmWffiMW Corporate Office: no.1071,Roacl no.44, Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad - 500 033,INDIA Prr:+.91(40) 4030100 -Mail:@ Diversionof 0.6943 of additionalforest landfor the construCtionof 24MW PauditalLassa HEP in favourof M/s G Pvt.Ltdl. -

Government of Himachal Pradesh

E1540 v6 GOVERNMENT OF Public Disclosure Authorized HIMACHAL PRADESH PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT HIMACHAL PRADESH ROAD AND OTHER DEVELOPMENT INFRASTRUCTURE CORPORATION (HPRIDC) Public Disclosure Authorized HIMACHAL PRADESH STATE ROADS PROJECT (HPSRP) Contract No.: HPSRP/WB/UG/5/ICB Name Public Disclosure Authorized of the Contract WIDENING AND STRENGTHENING THEOG-KOTKHAI-HATKOTI-ROHRU OF ROAD Environmental Management Plan VOL-2 FROM KM (0+000) TO (KM 80+684) Public Disclosure Authorized THE LOUIS BERGER GROUP, 2300 N Street, INC. NW Washington, D.C. B Tel.: 202 331 20037, USA 7775; Fax: 202 293 0787 Himachal State Roads Project Environmental Management plan (Theog-Kharapatthar-Rohru section) TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 ................................ ............................................... 1.2 1............ .................................. PROJECT BACKGROUNDI 1.2.1 FEASIBILITY FEASIBILITY STUDIES .................................................................STUDIES AND ALTERNATIVES2 1.2.2 ALTERNATIVES CONSIDERED 1.3 ............................................. ........................................ 2 .......... 1.3.1 ROAD 3 CROSS SECTIONS ..................................................................DESIGN PROPOSALS3 1.3.1.1 Proposed Cross Section Schedule 1.3.1.2 Realignment ................................. 3 Locations ........ 1.3.1.3 Retaining .................................... 3 Wall Locations ........ 1.3.1.4 Road ................................... 4 Side Drainage .............................................