National Register of Historic Places NAUONAI Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulk Trash & Brush Pick-Up Schedule

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS BULK TRASH & BRUSH PICK-UP SCHEDULE June 2020 MONDAY 1 WEDNESDAY 17 Arlington-West End (West), Central Pratt, South Pratt, Liberty Mason City, Woodland Park, Dolomite, Apple Valley, Sun Valley, Highlands, Smithfield, Woodlawn (West) Fairview TUESDAY 2 THURSDAY 18 South Titusville, Sandusky, North Pratt, Brown Springs, Gate City, Germania Park (South), Oakwood Place, Ensley #1 (35th St. to 20th Arlington-West End (East) St. Ensley), Spring Lake, Bush Hills, Rising/West Princeton WEDNESDAY 3 FRIDAY 19 Glen Iris, North Titusville, Oak Ridge, Sherman Heights, Oak Ridge West End Manor, Ensley #2 (20th St to 12th St. Ensley), Tuxedo, Park #1 (Antwerp Ave. to Crest Green Rd.), South Woodlawn, Huffman, East Thomas, Enon Ridge College Hills, Graymont MONDAY 22 THURSDAY 4 Arlington-West End (West), Central Pratt, South Pratt, Liberty Central City (East), East Birmingham (South), Five Points South, Highlands, Smithfield, Woodlawn (West) Wylam, North East Lake, Zion City, Druid Hills, Fountain Heights FRIDAY 5 TUESDAY 23 East Avondale, North Avondale, Ensley Highland (West), Woodlawn South Titusville, Sandusky, North Pratt, Brown Springs, Gate City, (East), Eastlake, Central City (West), East Birmingham (North), Arlington-West End (East) Evergreen, Norwood WEDNESDAY 24 MONDAY 8 Glen Iris, North Titusville, Oak Ridge, Sherman Heights, Oak Ridge Crestwood North, Oak Ridge Park #2 (Antwerp Ave. to 60th St. So.), Park #1 (Antwerp Ave. to Crest Green Rd.), South Woodlawn, Belview Heights (East – 5 Pts Av to Vinesville Rd), South East Lake #1 College Hills, Graymont (Red Oak Rd to 77th St. So), Collegeville TUESDAY 9 THURSDAY 25 Forest Park (South Avondale), Belview Heights (West – from Central City (East), East Birmingham (South), Five Points South, Vinesville Rd to Midfield/Fairfield), Green Acres, South Eastlake #2 Wylam, North East Lake, Zion City, Druid Hills, Fountain Heights (77th St. -

Annual Report 2010 Brochure

Annual Report 2010 Birmingham Public Library Annual Report 2010 o paraphrase Charles Dickens these are the best of times and the worst of times for the Birmingham Public Library. It is the worst of times because the library’s budget has been slashed for Fiscal Year 2011 and there is no relief in sight. The library’s acquisitions budget Twas cut 48 percent. The City of Birmingham’s Volunteer Retirement Incentive Plan (VRIP) netted a loss to the library of 25 positions (from a total of 170 full time positions) held by long time experienced library staff. The Mayor’s Office has at this time given us permission to fill only twelve of these positions. The loss of these 25 employees is greatest in the area of leadership. For many years the Birmingham Public Library (BPL) has depended on a leadership team made up of ten coordinators who oversee a function of the library or a geographical area of branches and public service. Six of the retirees were coordinators and the City will allow us to fill only one, the Information Technology Coordinator. In addition we will not be allowed to fill the second Associate Director position. The loss to our leadership team is almost fifty per cent. From a team of thirteen we will be a team of seven. Cuts to the budget of the Jefferson County Library Cooperative threaten BPL because the Cooperative provides the backbone of our day to day operations – our online library catalog, Internet access, and much more. These are the best of times for the Birmingham Public Library because we have the finest staff and board remaining who have the intelligence, creativity, and determination to rise to the many challenges of this crisis and continue the excellent service that is BPL’s tradition. -

Regular Meeting of the Council of the City Of

REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF BIRMINGHAM JULY 7, 2015 at 9:30 A.M. _________________________________ The Council of the City of Birmingham met in the Council Chambers of the City Hall of Birmingham on July 7, 2015 at 9:30 a.m., in regular meeting. The meeting was opened with prayer by Reverend Dr. Timothy L. Kelley, Pastor Southside Baptist Church The Pledge of Allegiance was led by Councilor Marcus Lundy, Jr. Present on Roll Call: Councilmembers Abbott Hoyt Lundy Parker Rafferty Scales Tyson Austin Absent Roberson The minutes of April 7, 2015 were approved as submitted. The following resolutions and ordinances designated as Consent Agenda items were introduced by the Presiding Officer: RESOLUTION NO. 1016-15 BE IT RESOLVED by the Council of the City of Birmingham that proper notice having been given to Ollie Mae Holyfield (Assessed Owner) JUL 7 2015 2 the person or persons, firm, association or corporation last assessing the below described property for state taxes, 1800 Avenue D Ensley & Garage in the City of Birmingham, more particularly described as: LOTS 23+24+25+26 BLK 18 C ENSLEY AS RECORDED IN MAP BOOK 0904, MAP PAGE 0003 IN THE OFFICE OF THE JUDGE OF PROBATE OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA (22-31-3-15-12). LOT SIZE 100' X 150' is unsafe to the extent that it is a public nuisance. BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED by said Council that upon holding such hearing, it is hereby determined by the Council of the City of Birmingham that the building or structure herein described is unsafe to the extent that it is a public nuisance and the Director of Planning, Engineering and Permits is hereby directed to cause such building or structure to be demolished. -

Jefferson County Delinquent Tax List

JEFFERSON COUNTY DELINQUENT TAX LIST BIRMINGHAM DIVISION 020-007.000 003-003.000 ABDULLAH NAEEMAH STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 34 PARCEL-ID: 29-00-19-1- FT TO POB S-26 T-17 W 257.6 FT TH SLY ALG RD TAX NOTICE LOT 67 BLK 7 CLEVELAND POB 82 FT SW OF INTER OF MUN-CODE: 39 INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 29-00-04-1- 016-011.000 SECT TWSP RANGE R-3 R/W 204.3 FT TH E 242.4 THE STATE OF ALABAMA TAX AND COST: $1102.80 SE RW OF 3RD AVE S & E/L PARCEL-ID: 29-00-17-3- ADAMS RAVONNA D 006-009.001 LOT 15 BLK 12 ROSEMONT TAX AND COST: $236.64 SECT TWSP RANGE FT TO POB JEFFERSON COUNTY STORM WATER FEE OF SW 1/4 014-001.000 CLEMENTS LOTS 17 18 & 19 BLK 11 TAX AND COST: $383.91 ALEXANDER TAMMY LYNN TAX AND COST: $162.57 SECT TWSP RANGE INCLUDED SEC 29 TP 17 R 2 TH CONT LOT 16 BLK 2 YEILDING MUN-CODE: 35 HIGHLAND LAKE LAND CO PB STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 01 ALLEN LARRY TAX AND COST: $635.89 UNDER AND BY VIRTUE OF 4729 COURT S SW 25 FT TH SE 140 FT TO & BRITTAIN SURVEY OF PARCEL-ID: 13-00-36-1- 13 PG 94 INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 22-00-04-2- MUN-CODE: 32 STORM WATER FEE A DECREE OF THE PROBATE BIRMINGHAM TRUST ALLEY TH GEORGE W SMITH 005-025.000 TAX AND COST: $3291.53 ALDHABYANI MUTLAQ 000-004.001 PARCEL-ID: 22-00-26-1- INCLUDED COURT OF SAID COUNTY MUN-CODE: 32 NE 25 FT ALG ALLEY TH NW TAX AND COST: $1275.78 LOT 25 BLK 5 STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 37 COM NW COR OF NE 1/4 OF 012-011.000 ALLIANCE WEALTH I WILL, ON THE MAY 22, PARCEL-ID: 29-00-08-2- 140 FT TO POB LYING IN STORM WATER FEE MEADOWBROOK ESTS INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 23-00-11-4- NW 1/4 SEC 4 TP 17S R 3W LOT 3 BLK 1 DRUID -

'"•Srasssgh REGISTRATION FORM

NFS Form 10-900 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV282008 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES '"•sraSSsgH REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name ___ Ramsay-McCormack Building other names/site number United Security Life Insurance Co. Building 2. Location street & number, 1823-1825 Avenue E (508 19th Street) Enslev not for publication N/A city or town _ Birmingham___________________ vicinity N/A state Alabama code cL county Jefferson code Q23 zip code 35218 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this [^nomination I I request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^} meets CH does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant M nationally I I statewide [x] locally. (I I See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title Date Alabama Historical Commission (State Historic Preservation Office) State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property I I meets I I does not meet the National Register criteria. (I I See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register. LJ See continuation sheet. f~] determined eligible for the National Register. -

THE ANDERSON SHERIFFS of JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA with Additional Materials for All Jefferson County Sheriffs from 1819 Forward

THE ANDERSON SHERIFFS OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA With additional materials for all Jefferson County Sheriffs from 1819 forward. Two of the early Jefferson County Sheriffs were Anderson, Peter August 7, 1835 - - August 25, 1838 August 25, 1841 - - August 23, 1844 August 12, 1847 - - August 17, 1850 and his son Anderson, Thomas A. September 2, 1880 - January, 1885 [?] Peter Anderson was the great-great-grandfather of Martha {Skinner} Thomas, and Thomas A. Anderson was her great-grandfather. Direct family links to those two early Sheriffs of Jefferson County stimulated this project. These materials were prepared January-May, 2004 by Carl O. Thomas & Martha S. Thomas Knoxville, Tennessee To the best of our knowledge, materials included here are generally in the public domain. Others should feel free to make use of these materials. In such cases, please provide reference to the original sources that are cited throughout the following text. 1 Appreciation A number of sources were used in preparing these materials. One important source was “A List Compiled in The Department of Southern History and Literature,” of the Birmingham Public Library, Birmingham, Alabama, September 16, 1943. A copy of that list was provided by the kindness of Jack and Judi Parker, Birmingham, Alabama. They also provided the photographs of old grave markers from the Pinson, Alabama area. Judi Parker also provided help with genealogical searches, and with historical information about the Pinson, Alabama area. Another important source was material found at the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department web site, identified in the text. This includes an historical listing, and a large - though not complete - gallery of photographs of past sheriffs. -

Best of Bham 62 Jazz Cat Ball - Supporting Neglected Animals Expertise of St

#abouttownmag APRIL 2016 COMPLIMENTARY best place to bring a first date best Margarita best charity event best girls night out our 1st annual readers’ poll best BBQ B Best of ham best neighborhood bar best sportsbar best new restaurant best late night bar best place to buy wine The Quality and Expertise of St. Vincent’s. April The Convenience of Walk-in Care. B best of ham abouttownsite.com INSIDE 15 Out and About 20 Pointe Ball - Hosted by the Alabama Ballet 22 Elevate the Stage - Benefiting Camp Smile-A-Mile 24 Bags and Brews - Presented by St. Vincent’s Hospital 26 Heart2Heart - Hosted aTeam Ministries 28 Gallery Bar - Grand Opening 30 Phoenix Ball - Supporting the Boys and Girls Clubs 34 G3 300 - Homes Party 36 A Better Way to Spend Valentine’s Day - Supporting Better Basics We offer walk-in care for minor injury and illness, 38 Christopher Showcase - Benefiting Open Hands Overflowing Hearts 40 Orange Theory - Grand Opening ranging from minor cuts that may need stitches to St. Vincent’s One Nineteen 41 Red Nose Ball - 24th Annual 42 Wild About Chocolate - Valentine Gala to coughs and cold. Open after hours and seven 44 A Night Under the Big Top - Presented By Glenwood Jr. Board 45 All Aces - Casino Night days a week, our center provides the quality and 7191 Cahaba Valley Road 47 Best of Bham 62 Jazz Cat Ball - Supporting Neglected Animals expertise of St. Vincent’s with the convenience Hoover, AL 35242 of walk-in care. We provide on-site diagnostics, COVER (205) 408-2366 Hannah Godwin at Bettola in Pepper Place advanced technology, a new state-of-the-art clothes and accessories by Elle in Crestline Village facility, and experienced and compassionate staff Mon.-Fri. -

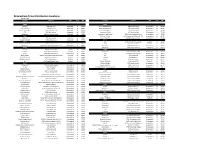

Birmingham Times Distribution Locations (By Zip Code) Location Address City State ZIP Location Address City State ZIP

Birmingham Times Distribution Locations (By Zip code) Location Address City State ZIP Location Address City State ZIP 35020 35209 Chevron 1228 18th St N Bessemer AL 35020 Sam's Mediterranean 932 Oxmoor Road Birmingham AL 35209 Valero 4th Ave 900 4th Ave N Bessemer AL 35020 Magic City Sweet Ice 715 Oak Grove Rd Birmingham AL 35209 Bessemer City Hall 1700 3rd Avenue N Bessemer AL 35020 Seed Coffee House 174 Oxmoor Road Birmingham AL 35209 CVS 901 9th Avenue Bessemer AL 35020 Homewood Diner 162 Oxmoor Road Birmingham AL 35209 Walgreens 1815 9th Avenue North Bessemer AL 35020 Homewood High School 1901 South Lakeshore Drive Birmingham AL 35209 35022 O'Henry's Coffee 569 Brookwood Village, Ste. 101 Birmingham AL 35209 Walmart 750 Academy Dr Bessemer AL 35022 Cocina Superior 587 Brookwood Village Birmingham AL 35209 Carnation Buffet 5020 Academy Ln Bessemer AL 35022 352010 35023 CVS 3300 Clairmont Plaza South Irondale AL 35210 Exxon 14th Street 1401 Carolina Ave Bessemer AL 35023 Shell 5400 Beacon Drive Irondale AL 35210 Walgreens 3025 Allison Bonnett Memorial Hwy Birmingham AL 35023 El Cazador 1540 Montclair Road Birmingham AL 35210 35064 New China 7307 Crestwood Bvd Crestwood AL 35210 Chevron 3640 R Scrushy Blvd Fairfield AL 35064 35211 Jet Pep 7150 Aaron Aranov Dr Fairfield AL 35064 Walgreens 668 Lomb Avenue SW Birmingham AL 35211 Shell 6620 Aaron Aronov Dr Birmingham AL 35064 CVS 632 Tuscaloosa Avenue Birmingham AL 35211 Miles College 5500 Myron Massey Blvd Lunchroom Fairfield AL 35064 BP 641 Lomb Ave Birmingham AL 35211 Fairfield Library -

Sketches of Alabama Towns and Counties

Sketches of Alabama Towns and Counties INDEX The index is in alphabetical order except for military units with numeric designations that appear in the index before the "A"s. To locate an indexed item, refer to the page number(s) following the item. Numbers enclosed in brackets refer to a volume. There are three volumes so each page number or sequence of page numbers will be preceded by a volume number. For example: Doe, John [2] 2, 5, 8-10 [3] 12-18 refers to items on John Doe found in Volume II [2] on pages 2, 5, and 8 through 10, and also in Volume III [3] on pages 12 through 18. A copy of the Indexer's Guide is available from the Alabama Genealogical Society P. O. Box 2296 800 Lakeshore Drive Birmingham, Alabama 35229-0001 The AGS Indexing Project Committee Charles Harris, President AGS (Chairman) Jyl Hardy Sue Steele-Mahaffey Carol Payne Jim Anderson Computer processing and document formatting provided by Micrologic, Inc., Birmingham, Alabama Special thanks to Yvonne Crumpler and Jim Pate, and the staff of the Department of Southern History and Literature, Birmingham Public Library. and the numerous volunteers who transcribed and proofed content for this index. © 2005 Alabama Genealogical Society, Inc. Birmingham, Alabama Sketches of Alabama Towns and Counties INDEX Abernathy, John [3] 172 MILITARY Abernathy, Lee [1] 223 A-cee [3] 483 5th Kentucky Regiment [3] 491 Acee, Erasmus L. [2] 210 5th United States Calvary [3] 89 Achuse Bay [2] 184 7th Alabama Regiment [2] 408 Acker, Naomi [1] 224 8th Arkansas Regiment [3] 491 Ackerville, -

Downtown Ensley & Tuxedo Junction

Downtown Ensley & Tuxedo Junction An Introductory History David B. Schneider Schneider Historic Preservation, LLC For the City of Birmingham and Main Street Birmingham, Inc. Downtown Ensley & Tuxedo Junction David B. Schneider Schneider Historic Preservation, LLC for the City of Birmingham and Main Street Birmingham, Inc. © 2009 Main Street Birmingham Inc. and Schneider Historic Preservation, LLC City of Birmingham ooooo Mayor City Council ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo Main Street Birmingham, Inc. Acknowledgmens ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo ooooo ooooo ooooo ooooo oooo ooo oooo oo oooooo oo ooo oo oo o ooo oo David B. Schneider Downtown Ensley & Tuxedo Junction i Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................1 Downtown Ensley Historic District ..........................................2 Downtown Ensley ....................................................................3 Beginnings ..........................................................................3 -

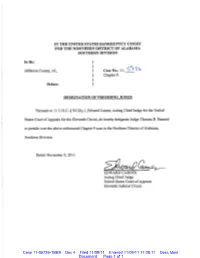

Case 11-05736-TBB9 Doc 4 Filed 11/09/11 Entered 11/09/11 17:08:11 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 1 Notice Recipients

Case 11-05736-TBB9 Doc 4 Filed 11/09/11 Entered 11/09/11 17:08:11 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 1 Notice Recipients District/Off: 1126−2 User: ldivers Date Created: 11/9/2011 Case: 11−05736−9 Form ID: pdfall Total: 5679 Recipients of Notice of Electronic Filing: aty John Patrick Darby [email protected] TOTAL: 1 Recipients submitted to the BNC (Bankruptcy Noticing Center): db Jefferson County, Alabama Room 280 Courthouse 716 North Richard Arrington Jr. Birmingham, AL 35203 7180254 2010−1 CRE Venture, LLC c/o Haskins W. Jones, Esq. Johnston Barton Proctor &Rose LLP 569 Brookwood Village, Ste. 901 Birmingham, AL 35209 7180255 3−GIS LLC 350 Market St. NE, Ste. C Decatur, AL 35601 7185233 A Carson Thompson #6 Pamona Ave. Homewood, AL 35209 7180287 A D I P.O. Box 409863 Atlanta, GA 30384−9863 7180504 A−Z Storage, LLC 500 Southland Dr. Ste. 212 Birmingham, AL 35226 7184574 A. C. Ruffin 5513 Ct. J Birmingham, AL 35208 7180644 A. G. Bellanca 2225 Pioneer Dr. Hoover, AL 35226 7180256 AAA Solutions Inc. P.O. Box 170215 Birmingham, AL 35217 7180257 AAEM 100 North Jackson St. Montgomery, AL 36104 7180261 ABC Cutting Contractors 3060 Dublin Cir. Bessemer, AL 35022 7180267 ACCA District Meetings 100 N Jackson Street Montgomery, AL 36104 7180284 ADCO Boiler Service 3657 Pine Ln. Bessemer, AL 35023 7180286 ADEM/Permits &Services P.O. Box 301463 Montgomery, AL 36130−1463 7180310 AKZO Nobel Paints LLC P.O. Box 905066 Charlotte, NC 38290−5066 7180337 AL Soc'y of Certified Public Accountants P.O. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1

NFS Fonn 10-900 OMB No. ID24-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name ________Flintridge Building other names/site number Tennessee Coal & Iron Co. Flint Ridge Building (H.A.E.R.) 2. Location street & number 6200 E. J. Oliver Boulevard not for publication N/A city or town Fairfield vicinity N/A state Alabama code AL countv Jefferson code 073 zip code 35064 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this [^nomination f"l request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property £<] meets l~l does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant f~| nationally fl statewide E<] locally, (fl See continuation sheet for additional comments.) iture of certifying official/Title Alabama Historical Commission (State Historic Preservation Office) State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property i~l meets (~l does not meet the National Register criteria. (l~l See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. Naffimal Park Service Certification ________ I, he/eby certify that this property is: QJ entered in the National Register. PI See continuation sheet. f~l determined eligible for the National Register.