Downtown Ensley & Tuxedo Junction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulk Trash & Brush Pick-Up Schedule

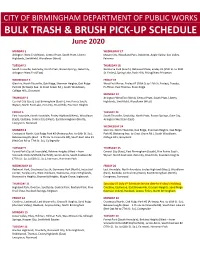

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS BULK TRASH & BRUSH PICK-UP SCHEDULE June 2020 MONDAY 1 WEDNESDAY 17 Arlington-West End (West), Central Pratt, South Pratt, Liberty Mason City, Woodland Park, Dolomite, Apple Valley, Sun Valley, Highlands, Smithfield, Woodlawn (West) Fairview TUESDAY 2 THURSDAY 18 South Titusville, Sandusky, North Pratt, Brown Springs, Gate City, Germania Park (South), Oakwood Place, Ensley #1 (35th St. to 20th Arlington-West End (East) St. Ensley), Spring Lake, Bush Hills, Rising/West Princeton WEDNESDAY 3 FRIDAY 19 Glen Iris, North Titusville, Oak Ridge, Sherman Heights, Oak Ridge West End Manor, Ensley #2 (20th St to 12th St. Ensley), Tuxedo, Park #1 (Antwerp Ave. to Crest Green Rd.), South Woodlawn, Huffman, East Thomas, Enon Ridge College Hills, Graymont MONDAY 22 THURSDAY 4 Arlington-West End (West), Central Pratt, South Pratt, Liberty Central City (East), East Birmingham (South), Five Points South, Highlands, Smithfield, Woodlawn (West) Wylam, North East Lake, Zion City, Druid Hills, Fountain Heights FRIDAY 5 TUESDAY 23 East Avondale, North Avondale, Ensley Highland (West), Woodlawn South Titusville, Sandusky, North Pratt, Brown Springs, Gate City, (East), Eastlake, Central City (West), East Birmingham (North), Arlington-West End (East) Evergreen, Norwood WEDNESDAY 24 MONDAY 8 Glen Iris, North Titusville, Oak Ridge, Sherman Heights, Oak Ridge Crestwood North, Oak Ridge Park #2 (Antwerp Ave. to 60th St. So.), Park #1 (Antwerp Ave. to Crest Green Rd.), South Woodlawn, Belview Heights (East – 5 Pts Av to Vinesville Rd), South East Lake #1 College Hills, Graymont (Red Oak Rd to 77th St. So), Collegeville TUESDAY 9 THURSDAY 25 Forest Park (South Avondale), Belview Heights (West – from Central City (East), East Birmingham (South), Five Points South, Vinesville Rd to Midfield/Fairfield), Green Acres, South Eastlake #2 Wylam, North East Lake, Zion City, Druid Hills, Fountain Heights (77th St. -

Brand New Beat

Ready for a BRAND NEW BEAT How “DANCING IN THE STREET” Became the Anthem for a Changing America MARK KURLANSKY Riverhead Books A member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. New York 2013 C H APT E R O N E ARE YOU RE ADY? or my generation rock was not a controversy, it was a fact. F My earliest memory of rock ’n’ roll is Elvis Presley. For others it may be Bill Haley or Chuck Berry. For people born soon after World War II, rock ’n’ roll was a part of childhood. The rock- ers, especially Elvis, are remembered as controversies. But there was no controversy among the kids. They loved the songs, their sense of mischief and especially the driving beat. The controversy came from adults. Only adults attacked Elvis or rock ’n’ roll. The controversy was only in their minds—on their lips. It was the begin- ning of what came to be known as “the generation gap,” a phrase coined by Columbia University president Grayson Kirk in April 1968, shortly before students seized control of his campus. There has never been an American generation that so identified with its music, regarded it as its own, the way the Americans who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s did. The music that started as a subversive movement took over the culture and became a huge, commercially dominant industry. The greatest of the many seismic shifts in the music industry is that young people became the target audience. In no previous generation had the main thrust of popular music been an attempt to appeal to people in their teens. -

Annual Report 2010 Brochure

Annual Report 2010 Birmingham Public Library Annual Report 2010 o paraphrase Charles Dickens these are the best of times and the worst of times for the Birmingham Public Library. It is the worst of times because the library’s budget has been slashed for Fiscal Year 2011 and there is no relief in sight. The library’s acquisitions budget Twas cut 48 percent. The City of Birmingham’s Volunteer Retirement Incentive Plan (VRIP) netted a loss to the library of 25 positions (from a total of 170 full time positions) held by long time experienced library staff. The Mayor’s Office has at this time given us permission to fill only twelve of these positions. The loss of these 25 employees is greatest in the area of leadership. For many years the Birmingham Public Library (BPL) has depended on a leadership team made up of ten coordinators who oversee a function of the library or a geographical area of branches and public service. Six of the retirees were coordinators and the City will allow us to fill only one, the Information Technology Coordinator. In addition we will not be allowed to fill the second Associate Director position. The loss to our leadership team is almost fifty per cent. From a team of thirteen we will be a team of seven. Cuts to the budget of the Jefferson County Library Cooperative threaten BPL because the Cooperative provides the backbone of our day to day operations – our online library catalog, Internet access, and much more. These are the best of times for the Birmingham Public Library because we have the finest staff and board remaining who have the intelligence, creativity, and determination to rise to the many challenges of this crisis and continue the excellent service that is BPL’s tradition. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

Modeling Musical Influence Through Data

Modeling Musical Influence Through Data The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:38811527 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Modeling Musical Influence Through Data Abstract Musical influence is a topic of interest and debate among critics, historians, and general listeners alike, yet to date there has been limited work done to tackle the subject in a quantitative way. In this thesis, we address the problem of modeling musical influence using a dataset of 143,625 audio files and a ground truth expert-curated network graph of artist-to-artist influence consisting of 16,704 artists scraped from AllMusic.com. We explore two audio content-based approaches to modeling influence: first, we take a topic modeling approach, specifically using the Document Influence Model (DIM) to infer artist-level influence on the evolution of musical topics. We find the artist influence measure derived from this model to correlate with the ground truth graph of artist influence. Second, we propose an approach for classifying artist-to-artist influence using siamese convolutional neural networks trained on mel-spectrogram representations of song audio. We find that this approach is promising, achieving an accuracy of 0.7 on a validation set, and we propose an algorithm using our trained siamese network model to rank influences. -

Alabama African American Historic Sites

Historic Sites in Northern Alabama Alabama Music Hall of Fame ALABAMA'S (256)381-4417 | alamhof.org 617 U.S. Highway 72 West, Tuscumbia 35674 The Alabama Music Hall of Fame honors Alabama’s musical achievers. AFRICAN Memorabilia from the careers of Alabamians like Lionel Richie, Nat King Cole, AMERICAN W. C. Handy and many others. W. C. Handy Birthplace, Museum and Library (256)760-6434 | florenceal.org/Community_Arts HISTORIC 620 West College Street, Florence 35630 W. C. Handy, the “Father of the Blues” wrote beloved songs. This site SITES houses the world’s most complete collection of Handy’s personal instruments, papers and other artifacts. Information courtesy of Jesse Owens Memorial Park and Museum alabama.travel (256)974-3636 | jesseowensmuseum.org alabamamuseums.org. 7019 County Road 203, Danville 35619 The museum depicts Jesse Owens’ athletic and humanitarian achieve- Wikipedia ments through film, interactive exhibits and memorabilia. Scottsboro Boys Museum and Cultural Center (256)609-4202 428 West Willow Street, Scottsboro 35768 The Scottsboro Boys trial was the trial pertaining to nine black boys allegedly raping two white women on a train. This site contains many artifacts and documents that substantiate the facts that this trial of the early 1930’s was the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. State Black Archives Research Center and Museum 256-372-5846 | stateblackarchives.net Alabama A&M University, Huntsville 35810 Unique archive museum center which serves as a repository of African Ameri- can history and culture providing a dialogue between present and past through archival collections and exhibits. Weeden House Museum 256-536-7718 | weedenhousemuseum.com 300 Gates Avenue, Huntsville 35801 Ms. -

Of Music. •,..,....SPECIAUSTS • RECORDED MUSIC • PAGE 10 the PENNY PITCH

BULK ,RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit N•. 24l9 K.C.,M •• and hoI loodl ,hoI fun! hoI mU9;cl PAGE 3 ,set. Warren tells us he's "letting it blow over, absorbing a lot" and trying to ma triculate. Warren also told PITCH sources that he is overwhelmed by the life of William Allan White, a journalist who never graduated from KU' and hobnobbed with Presidents. THE PENNY PITCH ENCOURAGES READERS TO CON Dear Charles, TR IBUTE--LETTERSJ ARTICLES J POETRY AND ART, . I must congratulate you on your intelli 4128 BROADWAY YOUR ENTR I ES MAY BE PR I NTED. OR I G I NALS gence and foresight in adding OUB' s Old KANSAS CITY, MISSDURI64111 WI LL NOT BE RETURNED. SEND TO: Fashioned Jazz. Corner to PENNY PITCH. (816) 561·1580 CHARLES CHANCL SR. Since I'm neither dead or in the ad busi ness (not 'too sure about the looney' bin) EDITOR .•...•. Charles Chance, Sr. PENNY PITCH BROADWAY and he is my real Ole Unkel Bob I would ASSISTING •.• Rev. Dwight Frizzell 4128 appreciate being placed on your mailing K.C. J MO 64111 ••. Jay Mandeville I ist in order to keep tabs on the old reprobate. CONTRIBUTORS: Dear Mr. Chance, Thank you, --his real niece all the way Chris Kim A, LeRoi, Joanie Harrell, Donna from New Jersey, Trussell, Ole Uncle Bob Mossman, Rosie Well, TIME sure flies, LIFE is strange, and NEWSWEEK just keeps on getting strang Beryl Sortino Scrivo, Youseff Yancey, Rev. Dwight Pluc1cemin, NJ Frizzell, Claude Santiago, Gerard and er. And speaking of getting stranger, l've Armell Bonnett, Michael Grier, Scott been closely following the rapid develop ~ Dear Beryl: . -

History of Jazz Tenor Saxophone Black Artists

HISTORY OF JAZZ TENOR SAXOPHONE BLACK ARTISTS 1940 – 1944 SIMPLIFIED EDITION INTRODUCTION UPDATE SIMPLIFIED EDITION I have decided not to put on internet the ‘red’ Volume 3 in my Jazz Solography series on “The History of Jazz Tenor Saxophone – Black Artists 1940 – 1944”. Quite a lot of the main performers already have their own Jazz Archeology files. This volume will only have the remainders, and also auxiliary material like status reports, chronology, summing ups, statistics, etc. are removed, to appear later in another context. This will give better focus on the many good artists who nevertheless not belong to the most important ones. Jan Evensmo June 22, 2015 INTRODUCTION ORIGINAL EDITION What is there to say? That the period 1940 - 1944 is a most exciting one, presenting the tenorsax giants of the swing era in their prime, while at the same time introducing the young, talented modern innovators. That this is the last volume with no doubt about the contents, we know what is jazz and what is not. Later it will not be that easy! That the recording activities grow decade by decade, thus this volume is substantially thicker than the previous ones. Just wait until Vol. 4 appears ... That the existence of the numerous AFRS programs partly compensates for the unfortunate recording ban of 1943. That there must be a lot of material around not yet generally available and thus not listed in this book. Please help building up our jazz knowledge base, and share your treasures with the rest of us. That we should remember and be eternally grateful to the late Jerry Newman, whose recording activities at Minton's and Monroe's have given us valuable insight into the developments of modern jazz. -

Magic City Jazz: John T. “Fess” Whatley and the Roots of the Birmingham Jazz Tradition

MAGIC CITY JAZZ: JOHN T. “FESS” WHATLEY AND THE ROOTS OF THE BIRMINGHAM JAZZ TRADITION Burgin Mathews A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum of Folklore. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Glenn Hinson Bill Ferris Patricia Sawin Tolton Rosser © 2020 Burgin Mathews ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT: Burgin Mathews: Magic City Jazz: John T. “Fess” Whatley and the Roots of the Birmingham Jazz Tradition (Under the direction of Glenn Hinson) The city of Birmingham, Alabama, was once home to a thriving music community that helped shape the sound and culture of jazz nationwide; at the heart of this tradition was a public schoolteacher named John T. “Fess” Whatley. Often consigned by historians to the footnotes or overlooked altogether, Black educators like Whatley played a key role in the development of jazz. But these educators’ training and impact were much more than musical. In the depths of the Jim Crow South, the music provided Black individuals and communities a means of affirmation and unity, communicated a set of cultural values, and equipped students with essential strategies for survival. Remarkably, this revolutionary work was achieved through the channels of formal education and in the face of pervasive segregation. As Whatley’s own innovations demonstrated, the very restrictions of African American industrial education could be refigured as an opportunity for creativity and empowerment. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to the four members of my thesis committee— Glenn Hinson Patricia Sawin Bill Ferris and Tolton Rosser —for graciously lending their time, support, insight, experience, and enthusiasm to this project. -

Regular Meeting of the Council of the City Of

REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF BIRMINGHAM JULY 7, 2015 at 9:30 A.M. _________________________________ The Council of the City of Birmingham met in the Council Chambers of the City Hall of Birmingham on July 7, 2015 at 9:30 a.m., in regular meeting. The meeting was opened with prayer by Reverend Dr. Timothy L. Kelley, Pastor Southside Baptist Church The Pledge of Allegiance was led by Councilor Marcus Lundy, Jr. Present on Roll Call: Councilmembers Abbott Hoyt Lundy Parker Rafferty Scales Tyson Austin Absent Roberson The minutes of April 7, 2015 were approved as submitted. The following resolutions and ordinances designated as Consent Agenda items were introduced by the Presiding Officer: RESOLUTION NO. 1016-15 BE IT RESOLVED by the Council of the City of Birmingham that proper notice having been given to Ollie Mae Holyfield (Assessed Owner) JUL 7 2015 2 the person or persons, firm, association or corporation last assessing the below described property for state taxes, 1800 Avenue D Ensley & Garage in the City of Birmingham, more particularly described as: LOTS 23+24+25+26 BLK 18 C ENSLEY AS RECORDED IN MAP BOOK 0904, MAP PAGE 0003 IN THE OFFICE OF THE JUDGE OF PROBATE OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA (22-31-3-15-12). LOT SIZE 100' X 150' is unsafe to the extent that it is a public nuisance. BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED by said Council that upon holding such hearing, it is hereby determined by the Council of the City of Birmingham that the building or structure herein described is unsafe to the extent that it is a public nuisance and the Director of Planning, Engineering and Permits is hereby directed to cause such building or structure to be demolished. -

Birmingham-Travel-Planners-Guide.Pdf

TRAVEL PLANNERS GUIDE *Cover Image: The Lyric Theatre was built in 1914 as a venue for performances by national vaudeville acts. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Lyric 2has | beenTRAVEL restored andPLANNERS is part of Birmingham’s GUIDE historic theater district which also includes the Alabama Theatre, a 1920s movie palace. TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME 07 WHAT TO DO 09 WHERE TO STAY 29 WHERE TO EAT (BY LOCATION) 53 BESSEMER/WEST 54 DOWNTOWN/SOUTHSIDE 54 EASTWOOD/IRONDALE/LEEDS 55 HOMEWOOD/MOUNTAIN BROOK/INVERNESS 55 HOOVER/VESTAVIA HILLS 55 BIRMINGHAM AREA INFORMATION 57 TRAVEL PLANNERS GUIDE | 3 GREATER BIRMINGHAM HOTELS 4 | TRAVEL PLANNERS GUIDE NORTH BIRMINGHAM DOWNTOWN BIRMINGHAM EAST BIRMINGHAM SOUTH BIRMINGHAM Best Western Plus Anchor Motel (45) American Interstate Motel (49) America’s Best Value Inn - Gardendale (1) Homewood/Birmingham (110) Apex Motel (31) America’s Best Inns Birmingham Comfort Suites Fultondale (5) Airport Hotel (46) America’s Best Value Inn & Suites - Cobb Lane Bed and Breakfast (43) Homewood/Birmingham (94) Days Inn Fultondale (8) America’s Best Inn Birmingham East (54) Courtyard by Marriott Birmingham Baymont Inn & Suites Fairfield Inn & Suites Birmingham Downtown/West (28) Americas Best Value Inn - Birmingham/Vestavia (114) Fultondale/I-65 (6) East/Irondale (65) Days Inn Birmingham/West (44) Best Western Carlton Suites Hotel (103) Hampton Inn America’s Best Value Inn - Leeds (72) Birmingham - Fultondale (4) DoubleTree by Hilton Birmingham (38) Candlewood Suites Birmingham/ Anchor Motel -

Jefferson County Delinquent Tax List

JEFFERSON COUNTY DELINQUENT TAX LIST BIRMINGHAM DIVISION 020-007.000 003-003.000 ABDULLAH NAEEMAH STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 34 PARCEL-ID: 29-00-19-1- FT TO POB S-26 T-17 W 257.6 FT TH SLY ALG RD TAX NOTICE LOT 67 BLK 7 CLEVELAND POB 82 FT SW OF INTER OF MUN-CODE: 39 INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 29-00-04-1- 016-011.000 SECT TWSP RANGE R-3 R/W 204.3 FT TH E 242.4 THE STATE OF ALABAMA TAX AND COST: $1102.80 SE RW OF 3RD AVE S & E/L PARCEL-ID: 29-00-17-3- ADAMS RAVONNA D 006-009.001 LOT 15 BLK 12 ROSEMONT TAX AND COST: $236.64 SECT TWSP RANGE FT TO POB JEFFERSON COUNTY STORM WATER FEE OF SW 1/4 014-001.000 CLEMENTS LOTS 17 18 & 19 BLK 11 TAX AND COST: $383.91 ALEXANDER TAMMY LYNN TAX AND COST: $162.57 SECT TWSP RANGE INCLUDED SEC 29 TP 17 R 2 TH CONT LOT 16 BLK 2 YEILDING MUN-CODE: 35 HIGHLAND LAKE LAND CO PB STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 01 ALLEN LARRY TAX AND COST: $635.89 UNDER AND BY VIRTUE OF 4729 COURT S SW 25 FT TH SE 140 FT TO & BRITTAIN SURVEY OF PARCEL-ID: 13-00-36-1- 13 PG 94 INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 22-00-04-2- MUN-CODE: 32 STORM WATER FEE A DECREE OF THE PROBATE BIRMINGHAM TRUST ALLEY TH GEORGE W SMITH 005-025.000 TAX AND COST: $3291.53 ALDHABYANI MUTLAQ 000-004.001 PARCEL-ID: 22-00-26-1- INCLUDED COURT OF SAID COUNTY MUN-CODE: 32 NE 25 FT ALG ALLEY TH NW TAX AND COST: $1275.78 LOT 25 BLK 5 STORM WATER FEE MUN-CODE: 37 COM NW COR OF NE 1/4 OF 012-011.000 ALLIANCE WEALTH I WILL, ON THE MAY 22, PARCEL-ID: 29-00-08-2- 140 FT TO POB LYING IN STORM WATER FEE MEADOWBROOK ESTS INCLUDED PARCEL-ID: 23-00-11-4- NW 1/4 SEC 4 TP 17S R 3W LOT 3 BLK 1 DRUID