The Strand Musical Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

// BOSTON T /?, SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THURSDAY B SERIES EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 wgm _«9M wsBt Exquisite Sound From the palace of ancient Egyp to the concert hal of our moder cities, the wondroi music of the harp hi compelled attentio from all peoples and a countries. Through th passage of time man changes have been mac in the original design. Tl early instruments shown i drawings on the tomb < Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C were richly decorated bv lacked the fore-pillar. Lato the "Kinner" developed by tl Hebrews took the form as m know it today. The pedal hai was invented about 1720 by Bavarian named Hochbrucker an through this ingenious device it b came possible to play in eight maj< and five minor scales complete. Tods the harp is an important and familij instrument providing the "Exquisi* Sound" and special effects so importai to modern orchestration and arrang ment. The certainty of change mak< necessary a continuous review of yoi insurance protection. We welcome tl opportunity of providing this service f< your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. HENRY B. CABOT President TALCOTT M. BANKS Vice-President JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer PHILIP K. ALLEN E. MORTON JENNINGS JR ABRAM BERKOWITZ EDWARD M. KENNEDY THEODORE P. -

CHAN 9859 Front.Qxd 31/8/07 10:04 Am Page 1

CHAN 9859 Front.qxd 31/8/07 10:04 am Page 1 CHAN 9859 CHANDOS CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 2 Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) AKG 1 In memoriam 11:28 Overture in C major in C-Dur . ut majeur Andante religioso – Allegro molto Suite from ‘The Tempest’, Op. 1 27:31 2 1 No. 1. Introduction 5:20 Andante con moto – Allegro non troppo ma con fuoco 3 2 No. 4. Prelude to Act III 1:58 Allegro moderato e con grazia 4 3 No. 6. Banquet Dance 4:39 Allegretto grazioso ma non troppo – Andante – Allegretto grazioso 5 4 No. 7. Overture to Act IV 5:00 Allegro assai con brio 6 5 No. 10. Dance of Nymphs and Reapers 4:21 Allegro vivace e con grazia 7 6 No. 11. Prelude to Act V 4:21 Andante – Allegro con fuoco – Andante 8 7 No. 12c. Epilogue 1:42 Andante sostenuto 3 CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 4 Sir Arthur Sullivan: Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ etc. Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ 36:02 Sir Arthur Sullivan would have been return to London a public performance in E-Dur . mi majeur delighted to know that the comic operas he of the complete music followed at the 9 I Andante – Allegro, ma non troppo vivace 13:21 wrote with W.S. Gilbert retain their hold on Crystal Palace Concert on 5 April 1862 10 II Andante espressivo 7:13 popular affection a hundred years after his under the baton of August Manns. -

Kalendár Výročí

Č KALENDÁR VÝROČÍ 2010 H U D B A Zostavila Mgr. Dana Drličková Bratislava 2009 Pouţité skratky: n. = narodil sa u. = umrel výr.n. = výročie narodenia výr.ú. = výročie úmrtia 3 Ú v o d 6.9.2007 oznámili svetové agentúry, ţe zomrel Luciano Pavarotti. A hudobný svet stŕpol… Muţ, ktorý sa narodil ako syn pekára a zomrel ako hudobná superstar. Muţ, ktorého svetová popularita nepramenila len z jeho výnimočného tenoru, za ktorý si vyslúţil označenie „kráľ vysokého cé“. Jeho zásluhou sa opera ako okrajový ţáner predrala do povedomia miliónov poslucháčov. Exkluzívny svet klasickej hudby priblíţil širokému publiku vystúpeniami v športových halách, účinkovaním s osobnosťami popmusik, či rocku a charitatívnymi koncertami. Spieval takmer výhradne taliansky repertoár, debutoval roku 1961 v úlohe Rudolfa v Pucciniho Bohéme na scéne Teatro Municipal v Reggio Emilia. Jeho ľudská tvár otvárala srdcia poslucháčov: bol milovníkom dobrého jedla, futbalu, koní, pekného oblečenia a tieţ obstojný maliar. Bol poverčivý – musel mať na vystú- peniach vţdy bielu vreckovku v ruke a zahnutý klinec vo vrecku. V nastupujúcom roku by sa bol doţil 75. narodenín. Luciano Pavarotti patrí medzi najväčších tenoristov všetkých čias a je jednou z mnohých osobností, ktorých výročia si budeme v roku 2010 pripomínať. Nedá sa v úvode venovať detailnejšie ţiadnemu z nich, to ani nie je cieľom tejto publikácie. Ţivoty mnohých pripomínajú román, ľudské vlastnosti snúbiace sa s géniom talentu, nie vţdy v ideálnom pomere. Ale to je uţ úlohou muzikológov, či licenciou spisovateľov, spracovať osudy osobností hudby aj z tých, zdanlivo odvrátených stránok pohľadu ... V predkladanom Kalendári výročí uţ tradične upozorňujeme na výročia narodenia či úmrtia hudobných osobností : hudobných skladateľov, dirigentov, interprétov, teoretikov, pedagógov, muzikológov, nástrojárov, folkloristov a ďalších. -

![[T] IMRE PALLÓ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5305/t-imre-pall%C3%B3-725305.webp)

[T] IMRE PALLÓ

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs FRANZ (FRANTISEK) PÁCAL [t]. Leitomischi, Austria, 1865-Nepomuk, Czechoslo- vakia, 1938. First an orchestral violinist, Pácal then studied voice with Gustav Walter in Vienna and sang as a chorister in Cologne, Bremen and Graz. In 1895 he became a member of the Vienna Hofoper and had a great success there in 1897 singing the small role of the Fisherman in Rossini’s William Tell. He then was promoted to leading roles and remained in Vienna through 1905. Unfor- tunately he and the Opera’s director, Gustav Mahler, didn’t get along, despite Pacal having instructed his son to kiss Mahler’s hand in public (behavior Mahler considered obsequious). Pacal stated that Mahler ruined his career, calling him “talentless” and “humiliating me in front of all the Opera personnel.” We don’t know what happened to invoke Mahler’s wrath but we do know that Pácal sent Mahler a letter in 1906, unsuccessfully begging for another chance. Leaving Vienna, Pácal then sang with the Prague National Opera, in Riga and finally in Posen. His rare records demonstate a fine voice with considerable ring in the upper register. -Internet sources 1858. 10” Blk. Wien G&T 43832 [891x-Do-2z]. FRÜHLINGSZEIT (Becker). Very tiny rim chip blank side only. Very fine copy, just about 2. $60.00. GIUSEPPE PACINI [b]. Firenze, 1862-1910. His debut was in Firenze, 1887, in Verdi’s I due Foscari. In 1895 he appeared at La Scala in the premieres of Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Silvano. Other engagements at La Scala followed, as well as at the Rome Costanzi, 1903 (with Caruso in Aida) and other prominent Italian houses. -

Le Corsaire Overture, Op. 21

Any time Joshua Bell makes an appearance, it’s guaranteed to be impressive! I can’t wait to hear him perform the monumental Brahms Violin Concerto alongside some fireworks for the orchestra. It’s a don’t-miss evening! EMILY GLOVER, NCS VIOLIN Le Corsaire Overture, Op. 21 HECTOR BERLIOZ BORN December 11, 1803, in Côte-Saint-André, France; died March 8, 1869, in Paris PREMIERE Composed 1844, revised before 1852; first performance January 19, 1845, in Paris, conducted by the composer OVERVIEW The Random House Dictionary defines “corsair” both as “a pirate” and as “a ship used for piracy.” Berlioz encountered one of the former on a wild, stormy sea voyage in 1831 from Marseilles to Livorno, on his way to install himself in Rome as winner of the Prix de Rome. The grizzled old buccaneer claimed to be a Venetian seaman who had piloted the ship of Lord Byron during the poet’s adventures in the Adriatic and the Greek archipelago, and his fantastic tales helped the young composer keep his mind off the danger aboard the tossing vessel. They landed safely, but the experience of that storm and the image of Lord Byron painted by the corsair stayed with him. When Berlioz arrived in Rome, he immersed himself in Byron’s poem The Corsair, reading much of it in, of all places, St. Peter’s Basilica. “During the fierce summer heat I spent whole days there ... drinking in that burning poetry,” he wrote in his Memoirs. It was also at that time that word reached him that his fiancée in Paris, Camile Moke, had thrown him over in favor of another suitor. -

August 1905) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1905 Volume 23, Number 08 (August 1905) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 23, Number 08 (August 1905)." , (1905). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/506 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PUBLISHER OF THE ETUDE WILL SUPPLY ANYTHING iN MUSIC 306 THE etude Just Published MUSIC SUPPLIES BY MAIL TO $1.00 Postpaid Teachers, Schools, Convents We will send any of the music in this list, or any of our other publi¬ and Conservatories of Music cations, “On Selection.” Complete catalogue mailed to any address WE SUPPLY ANYTHING IN MUSIC upon request. We grade all piano music from PROMPTLY, ECONOMICALLY, and SATISFACTORILY 1 (easy) to 7 (difficult). .• eiated with musical work in our colleges and other institutions of higher education, and the program Music Teachers’ National drew largely on men of this stamp. Among those INSTRUMENTAL present were Messrs. -

Portland Daily Press: November 23,1891

* * > f.*> ^——1———^———BgggggW————^^PORTLAND DAILY _ ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862-VOL. 30 PORTLAND MONDAY MAINE, MORNING, NOVEMBER 23, 181' I._{XSrS^.E&£i PRICE ST A YEAR, WHEN PAID IN ADVANCE S« ■ PKCIA1. NOTICKS. HOARD. termlaed that her relatives shall not get the PROMINENT MEN ITS ADVOCATES. DEATH OF REV. THOMAS her bis administration was her money. She prints in a D. D. presidents, yet wanted at 137 free st. SUNDAY following HILL, a WORK here: very Important one. For it was a: bis HIGHEST AWARD BoardersTable board $3 00; good rooms $1.00, newspaper BN Al . $1.SO and $2.00 per week. House heated by "I don’t want my my sick-bed. suggestion and by him that Harvard’s SIDES. steam. Boarders have free use of batn room. I don’t want them around by deatb-bed. I to Opinions Which Favor an Eight present extended 21-1 don’t want them to my and I A Printer’s President of system of elective stud- go funeral, Apprentice, ies don’t want them to get a dollar’s worth of Hour Working was my Day. Harvard and Crest Scholar. adopted. There had been electives Men Who to property after I am gone.” at WANTED By Hope Cap- Harvard before the time of Dr. Hill; She says her relatives have been at work but Water Was Scarce in the great which now so Very to secure her and she is deter- system, distin- or In ture a property, guishes reliable gentleman lady Convention. mined to thwart them. -

ARSC Journal

HISTORIC VOCAL RECORDINGS STARS OF THE VIENNA OPERA (1946-1953): MOZART: Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail--Wer ein Liebchen hat gafunden. Ludwig Weber, basso (Felix Prohaska, conductor) ••.• Konstanze ••• 0 wie angstlich; Wenn der Freude. Walther Ludwig, tenor (Wilhelm Loibner) •••• 0, wie will ich triumphieren. Weber (Prohaska). Nozze di Figaro--Non piu andrai. Erich Kunz, baritone (Herbert von Karajan) •••• Voi che sapete. Irmgard Seefried, soprano (Karajan) •••• Dove sono. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano (Karajan) . ..• Sull'aria. Schwarzkopf, Seefried (Karajan). .• Deh vieni, non tardar. Seefried (Karajan). Don Giovanni--Madamina, il catalogo e questo. Kunz (Otto Ackermann) •••• Laci darem la mano. Seefried, Kunz (Karajan) • ••• Dalla sua pace. Richard Tauber, tenor (Walter Goehr) •••• Batti, batti, o bel Masetto. Seefried (Karajan) •.•• Il mio tesoro. Tauber (Goehr) •••• Non mi dir. Maria Cebotari, soprano (Karajan). Zauberfl.Ote- Der Vogelfanger bin ich ja. Kunz (Karajan) •••• Dies Bildnis ist be zaubernd schon. Anton Dermota, tenor (Karajan) •••• 0 zittre nicht; Der Holle Rache. Wilma Lipp, soprano (Wilhelm Furtwangler). Ein Miidchen oder Weibchen. Kunz (Rudolf Moralt). BEETHOVEN: Fidelio--Ach war' ich schon. Sena Jurinac, soprano (Furtwangler) •••• Mir ist so wunderbar. Martha Modl, soprano; Jurinac; Rudolf Schock, tenor; Gottlob Frick, basso (Furtwangler) •••• Hat man nicht. Weber (Prohaska). WEBER: Freischutz--Hier im ird'schen Jammertal; Schweig! Schweig! Weber (Prohaska). NICOLAI: Die lustigen Weiher von Windsor--Nun eilt herbei. Cebotari {Prohaska). WAGNER: Meistersinger--Und doch, 'swill halt nicht gehn; Doch eines Abends spat. Hans Hotter, baritone (Meinhard von Zallinger). Die Walkilre--Leb' wohl. Hotter (Zallinger). Gotterdammerung --Hier sitz' ich. Weber (Moralt). SMETANA: Die verkaufte Braut--Wie fremd und tot. Hilde Konetzni, soprano (Karajan). J. STRAUSS: Zigeuner baron--0 habet acht. -

Tocc0262notes.Pdf

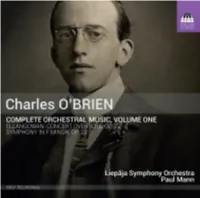

CHARLES O’BRIEN: A SCOTTISH ROMANTIC REDISCOVERED by John Purser Charles O’Brien was born in 1882 in Eastbourne, where his parents, normally based in Edinburgh, were staying for the summer season. His father, Frederick Edward Fitzgerald O’Brien, had worked as a trombonist in the first orchestra to be established in Eastbourne and there, in 1881, he had met and married Elise Ware. They would return there now and again, perhaps to visit her family, whose roots were in France: Elise’s grandfather had been a Girondin who had plotted against Robespierre and, in the words of Charles O’Brien’s son, Sir Frederick,1 ‘had to choose between exile and the guillotine. He chose the former and escaped to England, hence the Eastbourne connection’.2 Elise died tragically in 1919, after being struck by an army vehicle. As well as the trombone, Frederick Edward O’Brien played violin and viola and attempted, unsuccessfully, to teach his grandchildren the violin: ‘it was like snakes and ladders – one minor mistake and we had to start at the beginning again’, Sir Frederick recalled.3 Music went further back in the family than Charles’ father. His grandfather, Charles James O’Brien (1821–76) was also a composer and played the French horn, and his great-grandfather, Cornelius O’Brien (1775 or 1776–1867), who was born in Cork, was principal horn at Covent Garden. Charles O’Brien’s musical education was of the best. One of his early teachers was Thomas Henry Collinson (1858–1928) – father of the Francis Collinson who wrote The Traditional and National Music of Scotland.4 The elder Collinson was organist at St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, as well as conductor of the Edinburgh Choral Union, in which he was succeeded by O’Brien himself. -

Amalie Joachim's 1892 American Tour

Volume XXXV, Number 1 Spring 2017 Amalie Joachim’s 1892 American Tour By the 1890s, American audiences had grown accustomed to the tours of major European artists, and the successes of Jenny Lind and Anton Rubinstein created high expectations for the performers who came after them. Amalie Joachim toured from March to May of 1892, during the same months as Paderewski, Edward Lloyd, and George and Lillian Henschel.1 Although scholars have explored the tours of artists such as Hans von Bülow and Rubinstein, Joachim’s tour has gone largely unnoticed. Beatrix Borchard, Joachim’s biographer, has used privately held family letters to chronicle some of Joachim’s own responses to the tour, as well as a sampling of the reviews of the performer’s New York appearances. She does not provide complete details of Joachim’s itinerary, however, or performances outside of New York. Although Borchard notes that Villa Whitney White traveled with Joachim and that the two performed duets, she did not realize that White was an American student of Joachim who significantly influenced the tour.2 The women’s activities, however, can be traced through reviews and advertisements in newspapers and music journals, as well as brief descriptions in college yearbooks. These sources include the places Joachim performed, her repertoire, and descriptions of the condition of her voice and health. Most of Joachim’s performances were in and around Boston. During some of her time in this city, she stayed with her Amalie Joachim, portrait given to Clara Kathleen Rogers. friend, the former opera singer Clara Kathleen Rogers.