Five Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

501 Grammar & Writing Questions 3Rd Edition

501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 3rd Edition ® NEW YORK Copyright © 2006 LearningExpress, LLC. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by LearningExpress, LLC, New York. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 501 grammar & writing questions.—3rd ed. p. cm. ISBN 1-57685-539-2 1. English language—Grammar—Examinations, questions, etc. 2. English language— Rhetoric—Examinations, questions, etc. 3. Report writing—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Title: 501 grammar and writing questions. II. Title: Five hundred one grammar and writing questions. III. Title: Five hundred and one grammar and writing questions. PE1112.A15 2006 428.2'076—dc22 2005035266 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Third Edition ISBN 1-57685-539-2 For more information or to place an order, contact LearningExpress at: 55 Broadway 8th Floor New York, NY 10006 Or visit us at: www.learnatest.com Contents INTRODUCTION vii SECTION 1 Mechanics: Capitalization and Punctuation 1 SECTION 2 Sentence Structure 11 SECTION 3 Agreement 29 SECTION 4 Modifiers 43 SECTION 5 Paragraph Development 49 SECTION 6 Essay Questions 95 ANSWERS 103 v Introduction his book—which can be used alone, along with another writing-skills text of your choice, or in com- bination with the LearningExpress publication, Writing Skills Success in 20 Minutes a Day—will give Tyou practice dealing with capitalization, punctuation, basic grammar, sentence structure, organiza- tion, paragraph development, and essay writing. It is designed to be used by individuals working on their own and for teachers or tutors helping students learn or review basic writing skills. -

25, 1982 Every Thuradiy ,1 Wculislii, N

o THE WESTFIELD LEADER The Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper In Union County USPS (8(1020 Published SD YEAR, NO. 34 Second C'lav. Powngc Punt WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, MARCH 25, 1982 Every Thuradiy ,1 Wculislii, N. J. 20 Pages—25 Cents Pre-Hearing Dates Set iucCracken Resigns In School Staffers9 Disputes A Night of Debate The Westfield Board of Education has been notified As Councilman that two prehearing conferences for attorneys in the First Ward Councilman ing that the Town is being cases of two employees have been set by the New C. Chesney McCracken to- well served by the Council, Jersey Office of Administrative Law in Newark. One For the Town Council day announced his resigna- Administrator Jack Malloy of these involves the controversial suspension of tion from Town Council ef- and loyal town employees Stanley Ziobro, Roosevelt math teacher. Controversies beginning night. amending the land use law, Councilman John Brady fective immediately. too numerous to mention. The first prehearing conference, in the case of a in the conference room Discussion by the public, claiming that stipulations also asked council to con- In a letter to Ronald Fri- Sally and I look forward to custodian, is set for April 12 in the administrative law prior to its public session however, was minimal, concerning conditional use sider a substitute chemical gerio, Westfisld Town Re- the future but it will never court of Administrative Law Judge Ward R. Young. and ending with an abrupt and centered on concerns of properties for for use -

Sept 2010 TN.Indd

TOURING NEWS 1 GWTA National Office: P.O. Box 42403, Indianapolis, IN 46242 - Offi ce Hours: Monday - Friday 8:00am - 5:00pm EST Toll Free: 800-960-4982 Local: 317-243-6822 Fax: 317-243-6833 [email protected] [email protected] Chapter Listi ngs and additi onal info can be found online at: www.GWTA.org www.gotmotorcycle.org www.goldrushrally.org Executive Director Chairman of the Board Bruce & Linda Keenon Ed & Joanne Davis P.O. Box 348, Hunti ngton, IN 46750 1395 Sanborn Road, Yuba City, CA 95993 [email protected]; 260-358-0851; Fax 260-356-3392 ednjoanne@att .net; 530-673-7451 National Event Coordinator Life Member Board Representative Tony & Diane Manry Tom & Barb Johnson P.O. Box 469, Van Buren, IN 46991 401 Lincoln St., Bartelso, IL 62218 [email protected]; 765-934-4696 ridingcouple@fronti ernet.net; 618-765-2661 Webmaster Region D htt p://geociti es.com/gwtaregiond John Hunrath Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, 9265 Amarone Way, Sacramento, CA 95829 South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia [email protected]; 916-682-0734 Region Director: George & Debbie Deskins Rider Education Director 3330 Edmondson Ct. Murfreesboro, TN 37129 Don & Judy Coons [email protected]; 615-459-4418 P.O. Box 1164, Rogue River, OR 97537 Board Representati ve: Jim & Karen Quinn [email protected]; 541-582-1403 1368 Jason Circle, Ashland City, TN 37915 habatt [email protected]; 615-792-0546 Education and Retention Director Mike & Carol Brush Region E 12516 Poppleton Ave., Omaha, NE 68144 www.gwtaregione.homestead.com -

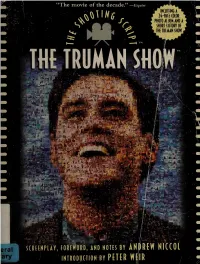

The Truman Show : the Shooting Script

: -\P* \ l l®j f* • w\ s . - ■ m, r-- '¥$*., _ -ur.cL Pf • “p- - ftt iO aLagjaL, ' iff ^ Svi G;’ 'Ijif kJltilll lid] P' j*i O' •! ;.- hi h Irygl^^ &L W. T< . ''^ -/.* l*A > ‘ ,L ,< ■ •* ' l , !?>’ { - il -i '' (■*« '.._■ ' ;$i| ■ -.• > > .•' ~ -— i -A •*' if SCRffNPLAY, TORIWORD, AND NOTH BY ANBRtW N 1C CO L INTRODUCTION BY PfTtR WtlR THE TRUMAN SHOW THE TRUMAN SNOW SCRKKPUY, TORIHORD, AND HOItS BY ANDREW NICCOL INTRODUCTION BY PETER WEIR 1 A Newmarket Shooting Script™ Series Book NEWMARKET PRESS • NEW YORK Cover art, screenplay, and all artwork © 1998 by Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved. Foreword and notes © 1998 by Andrew Niccol Introduction © 1998 by Peter Weir The Truman Show™ is a trademark of Paramount Pictures. This book is published simultaneously in the United States of America and in Canada. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole, or in part, in any form, without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to Permissions Department, Newmarket Press, 18 East 48th Street, New York, New York 10017. 10 98765432 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data available upon request ISBN 1-55704-367-1 Quantity Purchases Companies, professional groups, clubs, and other organizations may qualify for special terms when ordering quantities of this title. For information, write Special Sales, Newmarket Press, 18 East 48th Street, Suite 1501, New York, New York 10017, or caU (212) 832-3575, or fax (212) 832-3629. Manufactured in the United States of America OTHER NEWMARKET SHOOTING SCRIPTS™ INCLUDE Merlin: The Shooting Script The Birdcage: The Shooting Script U-Turn:The Shooting Script The Shawshank Redemption: The Shooting Script Swept from the Sea:The Shooting Script A Midwinter’s Tale: The Shooting Script The People vs. -

Monsters University

MONSTERS UNIVERSITY Story by Dan Scanlon Daniel Gerson & Robert L. Baird Screenplay by Daniel Gerson & Robert L. Baird Dan Scanlon 1. EXT. NEIGHBORHOOD - DAY A bird lands on the ground. It pecks at something, then the head stays up and another head pecks at the ground. It turns and we see that it has two heads. It squawks and flies off.... A SCHOOL BUS makes its way down the street. Singing can be heard from the kids inside. Pan up to reveal “Frighton Elementary” on the side of the bus. KIDS (singing) The neck bone’s connected to the: head bone. The head bone’s connected to the: horn bone. The horn bone’s right above the...wing bones. (laughing) The bus pulls into a parking lot. The bus doors open and a THIRD GRADE CLASS OF MONSTER KIDS pour through, pushing and yelling and laughing and being generally chaotic. KID #1 RAHR! KID #2 Ahh! KID #1 I scared you! KID #2 (laughing) No you didn't! MRS. GRAVES Okay, remember our field trip rules everyone: No pushing, no biting, and no fire-breathing. One of the kids breathes fire on one of his friends. FIRE STUDENT (breathing fire) RAHR! 2. A TEACHER MONSTER, MRS. GRAVES, stands over him, giving him a stern look. MRS. GRAVES What did I just say? (sigh) 18, 19...? Okay, we’re missing one. Who are we missing? ON THE CLOSED BUS DOORS. A little green hand knocks on the windowed doors. ON MRS. GRAVES. MRS. GRAVES (CONT’D) (realizing - this isn’t the first time...) Oooh, Mike Wazowski. -

Lockdown Games and Activities

LOCKDOWN GAMES AND ACTIVITIES We have some games & activities that may come in useful for families at home. If you have any games or activity ideas, please email [email protected] and I will add them to the list. We know that this is a challenging time for you, your family and our community. However, this time at home does give families opportunities to strengthen and build on their relationships in the home through games, activities, laughter and fun. Please let us know how you got on with the activities, we would love to hear from you. We will be updating this list regularly, so keep an eye out! For Prize’s for the winner or winning team, it could be a Reward. For example, they could pick a movie to watch that night/ they could do a favourite activity or choose their favourite meal for dinner or a snack. Click on any of these links for an area of interest to you: Video call Outdoor Online Indoors Games Video Call & Voice Call Games: 1. Hangman: Choose a word and draw a dash for each letter in the word. Have your partner guess a letter in the word. If the letter is in the word, draw it in the blank. If the letter is not in the word, begin drawing one part of the gallows. Your partner can keep guessing until you've drawn the entire gallows! LOCKDOWN GAMES AND ACTIVITIES 2. Quiz Time: This game would be great for video calls. It’s easy to create easy and gets everyone involved. -

BUSINESS of Spying for Soviets

r \ ZO - MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday. Aug. 9, 19B5 MANCHESTER I1 FOCUS 11 SPORTS 11 WEATHER Business In Brief BUSINESS Faucher suggests • Retired man recalls Defensive miscues H ot, humid today; Mary Kay salutes Lsko sharing firehous^ life aboard a 6-17 bring Po.st 102 down , clear, cooler tonight ... page 2 Marie Isko o l Manchester was honored ,Iuly,27 as one of the . ’ ... page 10 ' "...page 11 ( ’... page 15 saleswornen for Mary Kay Cosmetics Inc. of Dallas, Texas. Undergrouhd taxes worth billions . ^ . Company founder and chairman. Mary K ay Ash named Isko to the -tinue to mushroom. The whole Director Court oti^personal Sales, tration includes provisions to beef TheIRS,jcould purpose of tax "reform” loses, 'placing her in thevtop I percent of take in a min up enforcement — badly as it is meaning. Marj; Kay's 150,000salespeople.-Isko. imum of $90 bil- needed. Despite'widespread terror Your of the dreaded IRS audit, for An excellent starting"place ^ was owartfad ti’ gold and diamond lion a year would be tax shelters. The very necklace. ■ , more than now instanceT the IjRS examines less Money's than 2 percent of individual tax word "shelters" suggests evasion the honors came at Mary Kay's simply by going _ payer returns. When applied tp taxes. And.it's no' national seminar in Dallas. More into otir under Worth It obviou.s that the IRS needs secret by now that the IRS is than 20.000 women attended the ground econ '-5 and should gel more resources to devoting vast amounts of time and, seminar 'for product a.nd sales omy — and col Sylvia Porter 1 carry out existing law (not to- energy toward investigating abu-; M ■ training, raotivationandrecognition. -

Georgia School Bus Driver Training Manual, Available from the Department

PURPOSE The Georgia Department of Education Pupil Transportation Division has sought to further pupil transportation safety through school bus driver education programs throughout Georgia. The selection of suitable employees must be followed by instruction and training to ensure the employees will satisfactorily perform their duties in the manner expected. The Georgia Department of Education’s driver training manual was developed to provide a comprehensive course consistent with the goals of pupil transportation management to provide a safe, efficient and dependable service. This curriculum handbook also seeks to promote uniformity of instruction and the learning experience. While allowing for flexibility for all school systems, you should completely familiarize yourself with the course content so that you can customize the materials to satisfy local needs. Every effort has been made to present a comprehensive coverage in this manual. Table of Contents Section A A-1 – A-8 Requirements for Program School System’s Responsibility Driver Selection Driver Responsibility Section B B-1 – B-37 Instructional Strategies for the Bus Driver Trainer Organizing the Learning Environment Lesson Plan Preparation Effective Delivery of the Lesson Using Multiple Media Power Point Section C C-1 – C-118 Regular Transportation Content Unit 1 Georgia Laws for School Bus Operation Introduction Review of Relevant Laws; Georgia 20 Code Section Review of Relevant Laws; Georgia 40 Code Section Review of Georgia Board of Education Rules Content Unit 2 Traffic Control -

Social Card Games Sample

Social card games Ken Hutton © 2021 Ken Hutton. https://kenhutton.uk ISBN 978-1-9168759-1-3 Other available formats: • eBook: ISBN 978-1-9168759-0-6 Fonts are from the TeX Gyre colection – Bonum for the title on the cover and title page, Heros for other headings and Pagella (with Heros’ quote marks) for the main text. The main software used to create this book was: • GraphicsMagick and the GNU image manipulation program (GIMP) – for cover design and processing illustrations and score sheets. • The Vim text editor – to write and edit the content, markup and filter programs. • GNU Awk – to process the ebook’s xhtml and to convert it to ConTeXt. • epubcheck and Info-zip’s zip – to test and put together the ebook. • ConTeXt and pdfTeX – to generate the pdf for print. • git – to keep a record of edits and – if necessary – revert changes. • Guix system, Linux, GNU Make, Bourne-Again SHell (bash) and Coreutils – to stick all the other software together and make it work. All of that is Free Software, so thank you to everyone who has contributed to those projects and to the Free Software community at large. Contents Preface . 8 Introduction . 10 Shuffling the pack . 13 Packtopack ....................................... 13 The overhand shuffle . 14 The Indian shuffle . 15 Playing in turn . 16 Snap (2–10 players) .................................... 16 Packs, packets and piles . 17 Tricks ............................................ 18 French deck . 18 Capture games . 19 General rules for capture games . 20 Snapping . 20 Battle . 21 Slapjack (2–10 players) ................................. 22 Beggar thy neighbour (2–10 players) .................... 22 Snip snap snorem (2–10 players) ........................ -

Views from a School Bus Window : Stories of the Children Who Ride

University of Lethbridge Research Repository OPUS http://opus.uleth.ca Theses & Projects Faculty of Education Projects (Master's) 2004 Views from a school bus window : stories of the children who ride Robbins, Lorraine Lethbridge, Alta. : University of Lethbridge, Faculty of Education, 2004 http://hdl.handle.net/10133/836 Downloaded from University of Lethbridge Research Repository, OPUS VIEWS FROM A SCHOOL BUS WINDOW: STORIES OF THE CHILDREN WHO RIDE LORRAINE ROBBINS B.Ed., University of Lethbridge, 1978 A Project Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF EDUCATION FACULTY OF EDUCATION LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA February 2004 Dedication This project is dedicated to the rural children who ride school buses and to the students who I was able to interview. I thank them and their families for their help and support, and I hope that by writing their stories, a difference will be made to the rides that they will take everyday in the future. in Abstract Everyday, hundreds of students in rural areas of Alberta and other parts of Canada start their day by boarding a big yellow school bus, the vehicle that transports them to and from school. For them, their school day begins and ends with a bus ride. For many, the ride is lengthy. This study presents qualitative research that forms a profile of what concerns students about their bus rides. 62 children from ages 5 to 18 were interviewed to determine what they thought about riding the school bus and what social, psychological and intellectual implications exist for these children. -

Favorite Trick

Monday, Thoroughbred Daily News May 6, 2002 TDN For information, call (732) 747-8060. HEADLINE NEWS GODOLPHIN LEVEL THE SCORE Kazzia Takes the Lead... Kazzia (Ger) (Zinaad {GB}), sent off at 14-1, beat When the front-runner faded entering the dip, Kazzia Snowfire (GB) (Machiavellian) by a neck to provide was ready to take over before being driven out to as- Godolphin with their first Classic of 2002. Out of luck sert over the determined Snowfire. Alasha (Ire) with the colts in the G1 2000 Guineas dominated by (Barathea {Ire}) and Dolores (GB) (Danehill) closed fast, Ballydoyle on Saturday, Sheikh Mohammed’s operation but it was too late as Dettori had stolen the race up replied with Kazzia’s game success to level the scores. front. “I just wanted to find a nice, even stride and she “I had suggested to Sheikh Mohammed that we run her was going really nicely,” said Dettori. “Pat [Eddery] in the G2 Premio Regina Elena [Italian 1000 Guineas], came along and helped me but he wanted a runner here,” said Godolphin Racing and took me all the way to the Manager Simon Crisford. “She’s a really hard, tough line--she was very brave.” and resolute filly and she’s very honest. This has made Kazzia started her career un- up for a pretty moderate weekend so far.” Kazzia der the care of trainer Andreas captilalized on the withdrawal of Queen’s Logic (Ire) Wohler, taking a Hoppegarten (Grand Lodge) on the eve of the race, and the disap- maiden before winning the G3 pointing showing by Gossamer (GB) (Sadler’s Wells) in Premio Dormello in Milan in the race itself. -

Strike Settled Just As More Than 90 Bon L Barely a Week Old

See pages We turn three - it seems you like us 12 & 13 Thomas B. McPherson No Magic Colin A. Brown No Pills John T. Kalm No Machines Thomas McPherson Just You! & Associates ™ LAW FIRM You Better Cardio Kickboxing, T: 905-727-3151 at Watson’s Family Karate School F: 905-841-4395 Aurora’s Community Newspaper 40 Engelhard Dr., Unit 9 Aurora 905-727-7144 Vol. 4 No. 1 Week of October 14, 2003 905-727-3300 Strike settled Just as more than 90 Bon L barely a week old. Canada Inc. employees were set- But a lot happened in the seven- tling in to what looked like a long day walkout. strike, it was over. Included was a warning from the Members of Local 7193 of the American-based company that if United Steelworkers of America the strike did not end soon, the accepted its negotiating teams plant would close for good. advice to settle Friday afternoon. In addition, the union filed a com- The strike, at the Aurora Dunning plaint with the Labour Relations Avenue aluminum plant, was Board, contending unfair labour practices. Shortly before a provincially Rotarian supervised vote was to take place, the company modified its Don Moyer position of some issues including vacation time and health benefits. The union voted unanimously to dies at 87 accept the new offer which A familiar figure will be missing includes an annual 2 per cent from future Aurora Rotary Club wage hike for the next three meetings. years. Don Moyer, a long-time member Bon L operates from the plant of the club, died from pneumonia once owned by Alcan Aluminum, in hospital last Wednesday.