Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report: Communications Legislation

The Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Communications Legislation Amendment (Regional and Small Publishers Innovation Fund) Bill 2017 February 2018 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 ISBN 978-1-76010-710-9 Committee contact details PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6277 3526 Fax: 02 6277 5818 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.aph.gov.au/senate_ec This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. This document was printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra Committee membership Committee members Senator Jonathon Duniam, Chair LP, Tasmania Senator Janet Rice, Deputy Chair AG, Victoria Senator Anthony Chisholm ALP, Queensland Senator Linda Reynolds CSC LP, Western Australia Senator John Williams NATS, New South Wales Senator Anne Urquhart ALP, Tasmania Participating member for this inquiry Senator Sarah Hanson-Young AG, South Australia Senator Rex Patrick NXT, South Australia Committee secretariat Ms Christine McDonald, Committee Secretary Mr Colby Hannan, Principal Research Officer Ms Georgia Fletcher, Administration Officer iii iv Contents Committee membership ................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ..................................................................................... 1 Conduct of the inquiry ........................................................................................... -

Participating Publishers

Participating Publishers 1105 Media, Inc. AB Academic Publishers Academy of Financial Services 1454119 Ontario Ltd. DBA Teach Magazine ABC-CLIO Ebook Collection Academy of Legal Studies in Business 24 Images Abel Publication Services, Inc. Academy of Management 360 Youth LLC, DBA Alloy Education Aberdeen Journals Ltd Academy of Marketing Science 3media Group Limited Aberdeen University Research Archive Academy of Marketing Science Review 3rd Wave Communications Pty Ltd Abertay Dundee Academy of Political Science 4Ward Corp. Ability Magazine Academy of Spirituality and Professional Excellence A C P Computer Publications Abingdon Press Access Intelligence, LLC A Capella Press Ablex Publishing Corporation Accessible Archives A J Press Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta (AMMSA) Accountants Publishing Co., Ltd. A&C Black Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada Ace Bulletin (UK) A. Kroker About...Time Magazine, Inc. ACE Trust A. Press ACA International ACM-SIGMIS A. Zimmer Ltd. Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Fisicas y Acontecimiento A.A. Balkema Publishers Naturales Acoustic Emission Group A.I. Root Company Academia de Ciencias Luventicus Acoustical Publications, Inc. A.K. Peters Academia de las Artes y las Ciencias Acoustical Society of America A.M. Best Company, Inc. Cinematográficas de España ACTA Press A.P. Publications Ltd. Academia Nacional de la Historia Action Communications, Inc. A.S. Pratt & Sons Academia Press Active Interest Media A.S.C.R. PRESS Academic Development Institute Active Living Magazine A/S Dagbladet Politiken Academic Press Acton Institute AANA Publishing, Inc. Academic Press Ltd. Actusnews AAP Information Services Pty. Ltd. Academica Press Acumen Publishing Aarhus University Press Academy of Accounting Historians AD NieuwsMedia BV AATSEEL of the U.S. -

Bill Whittaker Award

Ken Linnett’s story of the life of Tulloch—Tulloch, the extraordinary life and times of a true champion—has won the 2018 Bill Whittaker Book Award. The award, commemorating the highly respected former racing writer Bill Whittaker, is presented every two years for the best book on horse racing published in Australia/New Zealand in that period. A total of 39 books were published on horse racing in 2016/2017, and presented for judging. Three fiction books and four for juveniles were excluded, leaving a total of 32 books eligible for the award. The criteria underpinning the award are that the book must: • add to the knowledge of Australian racing history. • be well written. • be well produced. The books short-listed were: Tulloch by Ken Linnett (Slattery Media Group). The Life and Times of Eric Connolly by John Macnaughtan (self-published). Good Losers Die Broke by Max Presnell (Allen & Unwin). Moods by Helen Thomas (Schwartz Publishing). A Long Way from Wyandra by Peter Moody with Trevor Marshallsea (Allen & Unwin). Subzero by Adam Crettenden (Penguin). Pumper by Jim Cassidy with Andrew Webster (Pan Mac Millan). Foul Luck & Outrageous Fortune by Rick Hore-Lacy (Sid Harta Publishers). Previous winners of the award were: 2010 The Master's Touch by Keith Paterson. (Runner-up, Phar Lap: the untold story by Graeme Putt). 2012 Peter Pan by Jessica Owers. 2014 Over the Hurdles by John Adams and Shannon by Jessica Owers, joint winners 2016 Heroes & Champions by Bob Charley. (Runner-up Mosstrooper by Peter Harris). . -

Aboriginal History and Identity

LIBRARY HOT TOPICS ABORIGINAL HISTORY AND IDENTITY The biggest estate on earth: how Dark emu: black seeds: Aborigines made Australia by Bill agriculture or accident? by Gammage. Crows Nest, NSW: Bruce Pascoe. [Tullamarine, Allen & Unwin, 2012. 305.89 GAM Victoria]: Bolinda Audio, [2017] CD 305.89 PAS “Across Australia, early Europeans commented again and again that the land Audiobook. Read by the author. 5 discs. looked like a park. With extensive grassy patches and pathways, open woodlands Growing up Aboriginal in and abundant wildlife, it evoked a country estate in England. Australia edited by Anita Heiss. Bill Gammage has discovered this was because Aboriginal people managed the land in a far more systematic and Carlton, Vic: Schwartz Publishing, scientific fashion than we have ever realised.” – Back cover. 2018. 305.89 GRO Constitutional recognition: First “Accounts from well-known authors and high- Peoples and the Australian settler profile identities sit alongside those from newly discovered writers of all ages. All of the state by Dylan Lino; foreword, contributors speak from the heart – Professor Megan Davis. Annandale, sometimes calling for empathy, oftentimes challenging NSW: The Federation Press, 2018. stereotypes, always demanding respect. This groundbreaking 305.89 LIN collection will enlighten, inspire and educate about the lives of Aboriginal people in Australia today.” – Publisher website. “With First Peoples continuing to press for the recognition of their sovereignty and peoplehood, this book will Hidden in plain view: the be a definitive reference point for scholars, advocates, policy- Aboriginal people of coastal makers and the interested public. Dr Dylan Lino, Constitutional Sydney by Paul Irish. -

University of Technology Sydney Sue Joseph the Essay As Polemical

Joseph The Essay as Polemical Performance University of Technology Sydney Sue Joseph The essay as polemical performance: ‘salted genitalia’ and the ‘gender card’ Abstract: On October 9, 2012, the then Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard rose to her feet in Canberra’s Parliament House, and, in response to a motion tabled by Opposition Leader Tony Abbott, delivered her blistering Misogyny Speech. Although Gillard’s speech was met with cynicism by the Australian Press Gallery, some accusing her of playing the ‘gender card’, it reverberated around the world and when the international coverage poured back into the country, many Australians stood up and listened. One of them was author, essayist, classical concert pianist and mother, Anna Goldsworthy. Shortly after the delivery of The Misogyny Speech, Quarterly Essay editor Chris Feik approached Goldsworthy to write the 50th essay for the Black Inc. publication with his idea to view this event through a cultural lens. It took several months to research and compose the characteristically long-form (25,000 word) essay that Quarterly Essay publishes every three months as a single volume; ‘Unfinished Business: Sex, Freedom and Misogyny’ was launched at the Wheeler Centre in Melbourne on July 1, 2013, five days after Julia Gillard was deposed from her prime ministership by Kevin Rudd. This paper takes a look back at the 50th issue of the Quarterly Essay, to discuss with its author her essay-writing process and the aftermath of publication. Goldsworthy is erudite as she looks at the construction of the essay, its contents, and her love of essay writing. Although she confesses to not having a definition for the form, she believes it does not matter; that its fluidity is a basic constituent element. -

Publisher and Property Developer Morry Schwartz on How to Win in Both Fields

Publisher and property developer Morry Schwartz on how to win in both fields Melbourne publisher Morry Schwartz is out of the property development business for the first time in 30 years. Peter Braig by Andrew Burke The closest thing Morry Schwartz has to a Sydney office is a table at Fratelli Paradiso. So it's no surprise that the Melbourne-based publisher and property developer has chosen to meet at the Potts Point institution as he gears up to launch the latest addition to his growing media and publishing empire – a thrice-yearly journal called Australian Foreign Affairs to add to The Monthly, theQuarterly Essay, The Saturday Paper and his imprints including Black Inc. and Nero. It's a sunny day and by the time I arrive at 12.30pm he's already been conducting meetings at a shaded outside table for hours. He quickly wraps up the last of them – with his newest editor, Jonathan Pearlman, who he's chosen to steer what Schwartz refers to as AFA – with vigorous agreement on the challenge China faces to lift hundreds of millions more out of poverty. With his grey, shoulder-length hair, black, slightly rumpled suit and white shirt without a tie, Schwartz reminds me a little of actor Christopher Lloyd in his Back to the Future guise. He is the personification of the migrant made good. Born in postwar Hungary to Jewish parents who had survived the Holocaust, he was smuggled across the border to Germany when he was one and spent most of the next nine years in Israel. -

ALW720 - Narrative Nonfiction: Stories of Place | Deakin University

09/29/21 ALW720 - Narrative Nonfiction: Stories of Place | Deakin University ALW720 - Narrative Nonfiction: Stories of View Online Place Bascom, T. (2013). Picturing the Personal Essay: A Visual Guide. Creative Nonfiction, 49, 6–10. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=tru e&db=hus&AN=90026665&site=ehost-live&scope=site Bell, G. (2011). In the rat room: reflections on the breeding house. In The best Australian essays 2011 (pp. 149–158). Black. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url=http://deakin.eblib.com.au/patron/Read.aspx?p=18 87415&pg=210 Bennett, A., & Royle, N. (2009). The uncanny. In An introduction to literature, criticism and theory (4th ed, pp. 35–43). Pearson/Longman. Bird, C. (2001). The cyclopedia: a short strange secret misty smoky mysterious history. In Storykeepers (pp. 57–67). Duffy & Snellgrove. Bishop, E. (1997). Questions of travel. In The Oxford book of travel stories (pp. 433–434). Oxford University Press. Blackman, B. (2003). Symptons of place. In A place on earth: an anthology of nature writing from Australia and North America (pp. 49–54). University of New South Wales Press. Carey, P. (2001). 30 days in Sydney: a wildly distorted account - Extracts. In 30 days in Sydney: a wildly distorted account (pp. 1–21). Bloomsbury. Cathcart, M. (2002). Uluru. In Words for country: landscape & language in Australia (pp. 207–221). University of New South Wales Press. Dessaix, R. (2012). Pushing against the dark: writing about the hidden self. Australian Book Review, 340, 32–40. http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=201204889;res=IELAPA Dillard, A. -

A Studyguide by Marguerite Olhara

A STUDYGUIDE BY MARGUERITE O’HARA www.metromagazine.com.au www.theeducationshop.com.au ANDREW DENTON TALKING TO THE MASCOT FROM ‘BANANAs’ CHRISTIAN TELEVISION PROGRAM ‘If God be for us, who can be against us?’ Romans 8:31 Introduction Andrew Denton, best known in Australia for his award-winning ABC Television interview program Enough Rope, went with a film crew to the 63rd National Religious Broadcasters Convention in Dallas, Texas in 2006. Over four days they filmed some of the proceedings and Denton interviewed a number of the 6000 delegates. n God on my Side (Anita Jacoby, about their beliefs and experiences. Denton focuses on the foot soldiers 2006) Denton questions some of of Christianity, the everyday believ- Ithe mainly evangelical, fundamen- Seventy million Americans are born ers running booths on the exhibition talist Christians, about the origins of again Christians. A highly organized, floor or workshops in the surrounding their personal faith and how this faith politicized and motivated bloc, they rooms. He takes people as he finds affects their view of the world, their provide more than forty per cent of them, allowing his interviewees room country and their President, George President Bush’s vote. As Moral Major- to express themselves freely, to have W. Bush. ity founder Jerry Falwell put it, ‘The their ideas and views heard. Republican Party does not have the The film is about faith and the places head count to elect a president without What he found was a multiplicity of it can take people. More than 6000 the support of religious conservatives.’ views. -

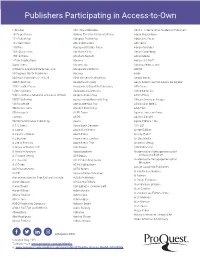

Publishers Participating in Access-To-Own

Publishers Participating in Access-to-Own Publisher ABG-Aqua Ediciones Adjuris - International Academic Publishers 10 Finger Press Abilene Christian University Press Adora Productions 111 Publishing Abington Publishing Adrenaline Press 12 Pines Press ABK Publications Adri Nerja 120 Pies Aboriginal Studies Press Adrián Gonzalez 13th Story Press Abraham Failla Adrian Greenberg 180° éditions Abraham Satoshi Adrian Melon 1-Take Publications Abrams Adriana LS Swift 2Leaf Press Abrams, Inc. Adriano Pereira Lima 3 Dreams Creative Enterprises, LLC Abrapalabra Editorial AECEP 30 Degrees South Publishers Abrasce Aedis 30 South Publishers (PTY) Ltd ABW Wissenschaftsverlag Aerilyn Books 306 Publishing Academia-Bruylant Aeryn Anders, Gerson Loyola De Aguilar 45th Parallel Press Academic & Scientific Publishers AFB Press 5 Sens Editions Acao Social Claretiana Aferre Editor S.L. 5 Sens Editions, Madame Anne-Lise Wittwer Acapella Publishing Affirm Press 5050 Publishing acasa Immobilienmarketing African American Images 50Minuten.de Ace Academics, Inc. African Sun Media 50Minutes.com Açedrex Publishing AGA/FAO 50Minutes.fr ACER Press Against the Grain Press 7Letras ACOG Agatha Albright 80/20 Performance Publishing Acoria Agora, Editora, Ltda A C U Press Acorn Book Services AIATSIS A capela Acorn Guild Press Aimee Sullivan A cigarra - eBooks Acorn Press Ainsley Quest A L Butcher Acorn Press, Limited Air Sea Media A Life In Print Inc Acorn Press, The Aisthesis Verlag A Sense of Nature LLC Acre Books AJR Publishing A Verba Futurorum Acrodacrolivres Akademische -

Holocaust Literature

Holocaust Literature An exploration of second-generation publication in Australia by Robin Ann Freeman Graduate Diploma of Professional Writing (Deakin) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Deakin University November 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Candidature declaration ii Abstract Vl Acknowledgments Vll Introduction 1 Writing Holocaust stories 2 Publishing Holocaust stories 7 Reading Holocaust stories 10 Methodology 12 1. An historical and cultural context to Australian book publishing of the late 20th century 17 A British hegemony: distributing books to the 'colonies' 18 Australia writes: a national voice, or commercial expediency? 20 Fighting back: Australian literature to the world? 23 The government intervenes: protection strategies for Australian consumers 25 The pendulum swings: Australian literature and the teacher critic 27 Authority and influence: creating reputations in the public sphere 30 Valuing culture: the diverse nature of the popular 33 The Australian book business: serendipity and strategies 36 2. The commodification of Australian writers 39 The conglomerate publisher: managing products for a healthy bottom line 40 Economics, ideology and commercialisation of the public sphere 42 The machinations of the Australian book retailing trade 44 Writers, editors and products 48 Promotions and publicity: a private life in a public sphere 53 The aspirational reader and the pleasure of 'knowing' 56 The unpredictable valuing of cultural objects 58 3. Inheriting the Holocaust: causal factors of second-generation writing 61 Berger's metaphor for the second generation 62 Self-healing and the building of a moral society 64 The characteristics of the second-generation witness 66 Memorial candles: the emotional burden of being someone else 72 Sharing common stories 74 Identity and the naming of Australian Jewishness 77 In search of the exiled self 83 4. -

From Mclibel to E-Libel: Recent Issues and Recurrent Problems in Defamation Law

From McLibel to e-Libel: Recent issues and recurrent problems in defamation law State Legal Convention 30 March 2015 J C Gibson Introduction 2014 was the year for concerns about proportionality, self-represented litigants, high legal costs, how to make the defence of partial justification work and the impact of social media. Although the matter complained of was a pamphlet rather than a blog1, very similar issues arose in the longest-running trial of any kind in English legal history, McDonalds Corporation v Steel and Morris [1997] EWHC 366 (“McLibel”2). This is a background paper for discussion of some of the recurring issues over the past twelve months, and is correspondingly written in an informal fashion. In particular, I want to consider is why, thirty years after the McLibel case began its long journey through the courts, these problems are not only still features of defamation law in Australia, but are exacerbated by the added complexity of online publication. The principal topics I have covered are: Social media and Internet cases: Although the evidence in some jurisdictions is equivocal3, the number of social media/Internet cases appears to be increasing4. 1 The matter complained of, a pamphlet entitled “What’s wrong with McDonalds?”, was published in 1986. The trial, which commenced on 28 June 1994, became the longest defamation trial on 11 December 1995 and, on 1 November 1996, the longest ever trial in English legal history. The 762-page judgment (delivered on 19 June 1997) was appealed all the way to the European Court of Human Rights, resulting in reduction of the damages from £60,000 to £40,000 and, in the ECHR ruling of 15 February 2005, a ruling that Articles 6 and 10 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms had been beached, coupled with an award of compensation to the defendants (see “McLibel: longest case in English history”, BBC, 15 February 2005). -

Red Flag Waking up to China’S Challenge Peter Hartcher

QUARTERLY ESSAY MEDIA RELEASE Red Flag Waking Up to China’s Challenge Peter Hartcher A gripping examination of China’s intentions and strategy when it comes to Australia China has become a key nation for Australia’s future – for our security, economy and identity. But what are China’s intentions when it comes to Australia? In this gripping account, Peter Hartcher shows how Beijing stepped up its campaign for influence, over hearts and minds, mineral and agricultural resources, media outlets and sea lanes. Reactions so far have included panic, xenophobia and all-the-way-with-the- USA, but the challenge now is to think hard about the national interest and respond with wisdom to a Release date: 25 November 2019 (DAILY) changed world. AU RRP: $22.99 NZ RRP: $26.00 ISBN: 9781863959704 This urgent, authoritative essay blends reporting and Imprint: Quarterly Essay analysis, and covers the local scene as well as the larger Format: Paperback geopolitical picture. It casts fresh light on Beijing’s Size: 234 x 167mm plans and actions, and outlines a way forward. Extent: 128pp “ Australia and China have got rich together. Subject: Politics & Government; Foreign Affairs For Australia, that is quite enough. But China’s government wants more. As much power and Embargo: influence over Australia as it can possibly get, Monday, 25 November 2019 using fair means or foul. But what Beijing can get is limited not only by China’s abilities, Media Enquiries: but also by Australia’s will. In each case where Anna Lensky Chinese officials or agents attempted to intrude, [email protected] they met Australian resistance.