The Prophet Muhammad's Covenants with Christian Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged

Press summary March 2015 Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged: Key Findings from the 2014 General Social Survey Michael Hout, New York University & NORC Tom W. Smith, NORC 10 March 2015 Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged: Key Findings from the 2014 General Social Survey March 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Most Groups Less Religious ....................................................................................................................... 3 Changes among Denominations .................................................................................................................. 4 Conclusions and Future Work....................................................................................................................... 5 About the Data ............................................................................................................................................. 6 References ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 About the Authors ....................................................................................................................................... -

Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 2 Article 3 Issue 1 African Catholicism: Retrospect and Prospect December 2017 Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria Mary Gloria Njoku Godfrey Okoye University, [email protected] Babajide Gideon Adeyinka ICT Polytechnic Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the African Studies Commons, Anthropology Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Community Psychology Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Developmental Psychology Commons, Health Psychology Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Multicultural Psychology Commons, Personality and Social Contexts Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Njoku, Mary Gloria and Adeyinka, Babajide Gideon (2017) "Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 3. p.24-51. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1020 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol2/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Catholicism by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. 34 MARY GLORIA C. NJOKU AND BABAJIDE GIDEON ADEYINKA Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria Mary Gloria C. Njoku holds a masters and Ph.D. in clinical psychology and an M.Ed. in information technology. She is a professor and the dean of the School of Postgraduate Studies and the coordinator of the Interdisciplinary Sustainable Development Research team at Godfrey Okoye University Enugu, Nigeria. -

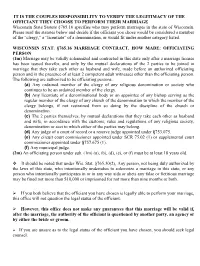

It Is the Couples Responsibility to Verify the Legitimacy Of

IT IS THE COUPLES RESPONSIBILITY TO VERIFY THE LEGITIMACY OF THE OFFICIANT THEY CHOOSE TO PERFORM THEIR MARRIAGE Wisconsin State Statute §765.16 specifies who may perform marriages in the state of Wisconsin. Please read the statutes below and decide if the officiant you chose would be considered a member of the “clergy,” a “licentiate” of a denomination, or would fit under another category listed. WISCONSIN STAT. §765.16 MARRIAGE CONTRACT, HOW MADE: OFFICIATING PERSON (1m) Marriage may be validly solemnized and contracted in this state only after a marriage license has been issued therefor, and only by the mutual declarations of the 2 parties to be joined in marriage that they take each other as husband and wife, made before an authorized officiating person and in the presence of at least 2 competent adult witnesses other than the officiating person. The following are authorized to be officiating persons: (a) Any ordained member of the clergy of any religious denomination or society who continues to be an ordained member of the clergy. (b) Any licentiate of a denominational body or an appointee of any bishop serving as the regular member of the clergy of any church of the denomination to which the member of the clergy belongs, if not restrained from so doing by the discipline of the church or denomination. (c) The 2 parties themselves, by mutual declarations that they take each other as husband and wife, in accordance with the customs, rules and regulations of any religious society, denomination or sect to which either of the parties may belong. -

Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK History Undergraduate Honors Theses History 5-2020 Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements Rachel Hutchings Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht Part of the History of Religion Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Citation Hutchings, R. (2020). Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements. History Undergraduate Honors Theses Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Honors Studies in History By Rachel Hutchings Spring 2020 History J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas 1 Acknowledgments: For my family and the University of Arkansas Honors College 2 Table of Content Introduction…………………………………….………………………………...3 Historiography……………………………………….…………………………...6 Surrender Agreements…………………………………….…………….………10 The Evolution of Surrender Agreements………………………………….…….29 Conclusion……………………………………………………….….….…...…..35 Bibliography…………………………………………………………...………..40 3 Introduction Beginning with Muhammad’s forceful consolidation of Arabia in 631 CE, the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates completed a series of conquests that would later become a hallmark of the early Islamic empire. Following the Prophet’s death, the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661) engulfed the Levant in the north, North Africa from Egypt to Tunisia in the west, and the Iranian plateau in the east. -

Controversies Over Islamic Origins

Controversies over Islamic Origins Controversies over Islamic Origins An Introduction to Traditionalism and Revisionism Mun'im Sirry Controversies over Islamic Origins: An Introduction to Traditionalism and Revisionism By Mun'im Sirry This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Mun'im Sirry All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6821-0 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6821-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................................... vii Introduction: Celebrating the Diversity of Perspectives ............................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 The Problem of Sources as a Source of Problems Sources of the Problem ......................................................................... 5 Towards a Typology of Modern Approaches ..................................... 20 Traditionalist and Revisionist Scholarship .......................................... 37 Faith and History ............................................................................... -

Al-'Usur Al-Wusta, Volume 25 (2017)

AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ 25 (2017) THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS About Middle East Medievalists (MEM) is an international professional non-profit association of scholars interested in the study of the Islamic lands of the Middle East during the medieval period (defined roughly as 500-1500 C.E.). MEM officially came into existence on 15 November 1989 at its first annual meeting, held in Toronto. It is a non-profit organization incorporated in the state of Illinois. MEM has two primary goals: to increase the representation of medieval scholarship at scholarly meetings in North America and elsewhere by co-sponsoring panels; and to foster communication among individuals and organizations with an interest in the study of the medieval Middle East. As part of its effort to promote scholarship and facilitate communication among its members, MEM publishes al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā (The Journal of Middle East Medievalists). EDITORS Antoine Borrut, University of Maryland Matthew S. Gordon, Miami University MANAGING EDITOR Christiane-Marie Abu Sarah, University of Maryland EDITORIAL BOARD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS, AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ (THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS) MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS Zayde Antrim, Trinity College President Sobhi Bouderbala, University of Tunis Sarah Bowen Savant, Aga Khan University Muriel Debié, École Pratique des Hautes Études Vice-President Malika Dekkiche, University of Antwerp Steven C. Judd, Fred M. Donner, University of Chicago Southern Connecticut State University David Durand-Guédy, Institut Français de Recherche en Iran Nadia Maria El-Cheikh, American University of Beirut Secretary Maribel Fierro, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas Antoine Borrut, University of Maryland Emma Gannagé, Georgetown University Denis Genequand, University of Geneva Treasurer Eric Hanne, Florida Atlantic Universit Ahmet Karamustafa, University of Maryland Étienne de La Vaissière, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Board Members Stephennie Mulder, The University of Texas at Austin Kristina L. -

Patricia CRONE (28 Mart 1945-11 Temmuz 2015)

−אء/Vefeyât/Obituary Patricia CRONE (28 Mart 1945-11 Temmuz 2015) İslâmî ilimler bilhassa İslâm tarihi alanında yaptığı şarkiyat çalışmaları ile bilinen Danimarka asıllı Ameri- kalı araştırmacı Patricia Crone, 2011 yılında teşhis ko- nulan akciğer kanseri sebebiyle 11 Temmuz 2015’te New Jersey, Princeton’da 70 yaşında öldü. Patricia Crone, Danimarka’nın Lejre kentinin Kyn- delose adlı kasabasında 28 Mart 1945’te dünyaya geldi. 1969 yılında Kopenhag Üniversitesi’nde lisans eğitimini tamamladı. Ardından Fransızca öğrenmek için Paris’e ve sonrasında İngilizceyi geliştirmek için Londra’ya git- meyi istedi. Londra’daki King’s College’da occasional student (misafir öğrenci) olarak kabul edildi. Medieval European History (Ortaçağ Avrupa Tarihi) okudu ve kilise-devlet ilişkileri alanında derslere devam etti. Londra Üniversi- tesi School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS)’ta öğrenim görmeye baş- ladı. Burada Arapça, Farsça, Süryanice öğrendi. SOAS’ta Bernard Lewis danış- manlığında Emevîler döneminde mevâlî üzerine çalıştığı doktorasını 1974’de bitirdi. Doktorasını bitirir bitirmez yine aynı üniversitede Warbung Insti- tute’de araştırma görevlisi olarak çalışmaya başladı. 1977 yılında Oxford Üni- versitesi’nde İslâm tarihi alanında Öğretim Görevliliğine ve yine aynı üniver- sitede Jesus College’de öğretim üyeliğine başladı. Burada on üç sene ders ver- dikten sonra Cambridge Üniversitesi’nde Islamic Studies (İslâmî İlimler) ala- nında Yardımcı Doçent ve Gonville and Caius College’de öğretim üyesi olarak çalıştı (1990-1992). Aynı kurumda doçent olarak 1992-1994 yıllarında görev yaptı. Patricia Crone, sonrasında Cambridge Üniversitesi Faculty of the Insti- tute’de 1994-1997 yılları arasında doçent olarak çalışmalarına devam etti. 1997 senesinde Princeton (the Institute for Advanced Study, School of Historical Studies) İleri Araştırmalar Enstitüsünde Tarih Araştırmaları Fakültesi’nde Andrew W. -

Constructing God's Community: Umayyad Religious Monumentation

Constructing God’s Community: Umayyad Religious Monumentation in Bilad al-Sham, 640-743 CE Nissim Lebovits Senior Honors Thesis in the Department of History Vanderbilt University 20 April 2020 Contents Maps 2 Note on Conventions 6 Acknowledgements 8 Chronology 9 Glossary 10 Introduction 12 Chapter One 21 Chapter Two 45 Chapter Three 74 Chapter Four 92 Conclusion 116 Figures 121 Works Cited 191 1 Maps Map 1: Bilad al-Sham, ca. 9th Century CE. “Map of Islamic Syria and its Provinces”, last modified 27 December 2013, accessed April 19, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilad_al-Sham#/media/File:Syria_in_the_9th_century.svg. 2 Map 2: Umayyad Bilad al-Sham, early 8th century CE. Khaled Yahya Blankinship, The End of the Jihad State: The Reign of Hisham Ibn ʿAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994), 240. 3 Map 3: The approximate borders of the eastern portion of the Umayyad caliphate, ca. 724 CE. Blankinship, The End of the Jihad State, 238. 4 Map 4: Ghassanid buildings and inscriptions in Bilad al-Sham prior to the Muslim conquest. Heinz Gaube, “The Syrian desert castles: some economic and political perspectives on their genesis,” trans. Goldbloom, in The Articulation of Early Islamic State Structures, ed. Fred Donner (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2012) 352. 5 Note on Conventions Because this thesis addresses itself to a non-specialist audience, certain accommodations have been made. Dates are based on the Julian, rather than Islamic, calendar. All dates referenced are in the Common Era (CE) unless otherwise specified. Transliteration follows the system of the International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES), including the recommended exceptions. -

Pakistan 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

PAKISTAN 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution establishes Islam as the state religion and requires all provisions of the law to be consistent with Islam. The constitution states, “Subject to law, public order, and morality, every citizen shall have the right to profess, practice, and propagate his religion.” It also states, “A person of the Qadiani group or the Lahori group (who call themselves Ahmadis), is a non-Muslim.” The courts continued to enforce blasphemy laws, punishment for which ranges from life in prison to execution for a range of charges, including “defiling the Prophet Muhammad.” According to civil society reports, there were at least 84 individuals imprisoned on blasphemy charges, at least 29 of whom had received death sentences, as compared with 77 and 28, respectively, in 2018. The government has never executed anyone specifically for blasphemy. According to data provided by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), police registered new blasphemy cases against at least 10 individuals. Christian advocacy organizations and media outlets stated that four Christians were tortured or mistreated by police in August and September, resulting in the death of one of them. On January 29, the Supreme Court upheld its 2018 judgment overturning the conviction of Asia Bibi, a Christian woman sentenced to death for blasphemy in 2010. Bibi left the country on May 7, after death threats made it unsafe for her to remain. On September 25, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction of a man who had spent 18 years in prison for blasphemy. On December 21, a Multan court sentenced English literature lecturer Junaid Hafeez to death for insulting the Prophet Muhammad after he had spent nearly seven years awaiting trial and verdict. -

Measuring the Impact of Religious Affiliation on LGBTQ-Inclusive Education Practices

Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 185, 19-31 Religious Belief and the Queer Classroom: Measuring the Impact of Religious Affiliationon LGBTQ-Inclusive Education Practices Tracey Peter, University of Manitoba Abstract This study examines the influence of religious affiliation on lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, two spirit, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ)-inclusive practices. Using data from a national survey of educators from pre-kindergarten to grade 12, multivariate analyses of variance models were employed in order to test the effects of religious affiliation on several LGBTQ-inclusive outcome measures. Results show that reli- gious affiliation does have a significant impact on the likelihood that educators will (or will not) practice LGBTQ-inclusive education, however, the pathways to such practices vary considerably across religious groupings. Recommendations are suggested in terms of intervention, inclusive teaching practices, visibil- ity, and leadership. Keywords: LGBTQ-inclusive education, homophobia, transphobia, religious affiliation, teachers, Canada Religious faith is often characterized in Canadian media as being in conflict with LGBTQ-inclusive teach- ing practices and education, and scholars have reported on a number of clashes between religious rights claims and LGBTQ equality rights (MacDougall & Short, 2010). When legislation was proposed in the three Canadian provinces of Ontario, in 2011, Manitoba, in 2012, and Alberta, in 2014, to support Gay Straight Alliances (GSAs) and other LGBTQ-inclusive interventions, there was, indeed, organized op- position from a wide range of faith communities (Liboro, Travers, & St. John, 2015; Short, 2012). Such opposition has also been supported in research as previous studies have found an association between reli- gious views against sexual and gender diversity with willingness to practice LGBTQ-inclusive education or intervene when witnessing homophobic or transphobic harassment (Taylor, Peter et al., 2015). -

Church of the Nativity, Leawood Facilities Director, David Stephens [email protected] IT Director, Nancy West [email protected] Visit

CHURCH CHURCH OFOF THETHE NATIVITYNATIVITY Nativity Ministry Opportunities and Phone Directory 2017 - 2018 COMPLETE TIRE & AUTO SERVICE 6717 W. 119TH ST. • OVERLAND PARK, KS 66209 • 913-345-1380 PHONE | BVGOODYEAR.COM † All Major Brand Tires † Computerized Engine Analysis † Heating & Air Conditioning † Wheel Balance/Alignment † Transmission Maintenance/Repair † Belts & Hoses † Tire Rotation † Cooling System Maintenance † Batteries † ShocksCELEBRATING & Struts † Manufacturer’s Preventive Maintenance30 YEARS Closed Sunday to pray for our customers Peggy & Bill Oades, Owners & Nativity Parishioners ©2017 Liturgical Publications Inc (800) 950-9952 • (262) 785-9952 • Dir. 02-00715-D / 52-630 Table of Contents Staff Directory 2 VIRTUS Training 3 Liturgy and Prayer 3 Formation 5 Ministries of Care 6 Parish Life 7 Stewardship 9 Membership Listing 10 Helpful Numbers Catholic Chancery Of ces Switchboard 913.721.1570 Superintendent of Catholic Schools Dr. Kathleen O’Hara 913.647.0321 Catholic Charities Administrative Of ce 913.433.2100 Catholic Cemeteries Switchboard 913.371.4040 Catholic Community Hospice Trudy Walker 913.621.5090 Catholic Youth Organization Switchboard 913.384.7377 Prairie Star Ranch Dcn. Dana Nearmyer 785.746.5693 Index of Advertisers These are our business and professional friends who have made this Parish Directory possible at no cost to our parish. We thank them for their involvement and encourage you to utilize their services. BC = Back Cover IFC = Inside Front Cover IBC = Inside Back Cover AUTOMOTIVE LANDSCAPING Blue Valley Goodyear. IFC Miller Tree Service . 41 BEER/WINE/SPIRITS RESTAURANTS Lukas Wine & Spirits Superstore. 42 Corner Bakery Cafe . IFC CLOTHING/RETAIL SCHOOL Laura’s Couture Collection . IBC Rockhurst High School . 42 FUNERARY SERVICES SENIOR LIVING McGilley Memorial Chapels . -

Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem

Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem Introduction The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem is a major Christian holy site, as it marks the traditional place of Christ's birth. It is also one of the oldest surviving Christian churches. In the Bible The birth of Jesus is narrated in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Matthew gives the impression that Mary and Joseph were from Bethlehem and later moved to Nazareth because of Herod's decree, while Luke indicates The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem that Mary and Joseph were from Nazareth, and Jesus was born in Bethlehem while they were in town for a special census. Scholars tend to see these two stories as irreconcilable and believe Matthew to be more reliable because of historical problems with Luke's version. But both accounts agree that Jesus was born in Bethlehem and raised in Nazareth. According to Luke 2:7 (in the traditional translation), Mary "laid him in a manger because there was no room for them in the inn." But the Greek can also be rendered, "she laid him in a manger because they had no space in the room" — we The Door of Humility – only about 4 feet high should perhaps imagine Jesus being born in a quiet back room of an overflowing one‐room house. The gospel accounts don't mention a cave, but less than a century later, both Justin Martyr and the Protoevangelium of James say Jesus was born in a cave. This is reasonable, as many houses in the area are still built in front of a cave.