Faith and Science Dialogue in the Shroud of Turin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

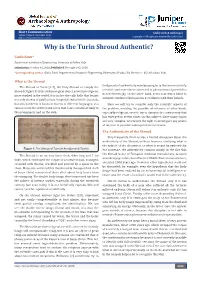

Why Is the Turin Shroud Not Fake?

Short Communication Glob J Arch & Anthropol Volume 7 Issue 3 - December 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Giulio Fanti DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.07.555715 Why is the Turin Shroud Not Fake? Giulio Fanti* Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Padua, Italy Submission: November 23, 2018; Published: December 04, 2018 *Corresponding author: Giulio Fanti, Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Padua, Via Venezia 1 - 35131Padova, Italy Summary The Turin Shroud [1-11], the Holy Shroud or simply the Shroud (Figure 1) is the archaeological object, as well as religious, more studied in it is also religiously important because, according to the Christian tradition, it shows some traces of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. A recent paperthe world. [12] From showed a scientific why and point in which of view, sense it is the important Shroud becauseis authentic, it shows but manya double persons image still of a keep man onup statingto now thenot contrary,reproducible probably nor explainable; pushed by important Relic of Christianity based on their personal religious aspects thus publishing goal-oriented documents. their religion beliefs that arouses many logical-deductive problems. Consequently, some researchers influence the scientific aspects of the most Figure 1: The Turin Shroud (left) and its negative image (right) with zoom of the face in negative (center) with the bloodstains in positive. This work considers some debatable facts frequently offered during the discussions about the Shroud authenticity, by commenting a recent The assertions under discussion are reported here in bold for clearness. paper [13]. Many claims, apparently contrary to the Shroud authenticity, appear blind to scientific evidence and therefore require clarifications. -

Rebuttal to Joe Nickell

Notes Lorenzi, Rossella- 2005. Turin shroud older than INQUIRER 28:4 (July/August), 69; with thought. News in Science (hnp://www.abc. 1. Ian Wilson (1998, 187) reported that the response by Joe Nickell. net.au/science/news/storics/s 1289491 .htm). 2005. Studies on die radiocarbon sample trimmings "are no longer extant." )anuary 26. from the Shroud of Turin. Thermochimica 2. Red lake colors like madder were specifically McCrone, Walter. 1996. Judgment Day for the -4CM 425: 189-194. used by medieval artists to overpaim vermilion in Turin Shroud. Chicago: Microscope Publi- Sox, H. David. 1981. Quoted in David F. Brown, depicting "blood" (Nickell 1998, 130). cations. Interview with H. David Sox, New Realities 3. Rogers (2004) does acknowledge that Nickell, Joe. 1998. Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: 4:1 (1981), 31. claims the blood is type AB "are nonsense." Latest Scientific Findings. Amherst, N.Y.: Turin shroud "older than thought." 2005. BBC Prometheus Books. News, January 27 (accessed at hnp://news. References . 2004. The Mystery Chronicles. Lexington, bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/—/2/hi/scicnce/naturc/421 Damon, P.E., et al. 1989. Radiocarbon dating of Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky. 0369.stm). the Shroud of Turin. Nature 337 (February): Rogers, Raymond N. 2004. Shroud not hoax, not Wilson, Ian. 1998. The Blood and the Shroud New 611-615. miracle. Letter to the editor, SKEPTICAL York: The Free Press. Rebuttal to Joe Nickell RAYMOND N. ROGERS oe Nickell has attacked my scien- results from Mark Anderson, his own an expert on chemical kinetics. I have a tific competence and honesty in his MOLE expert? medal for Exceptional Civilian Service "Claims of Invalid 'Shroud' Radio- Incidentally, I knew Walter since the from the U.S. -

Progress of Research on the Shroud of Turin

Why we Can See the Image by Robert A. Rucker August 17, 2019 www.shroudresearch.net © 2019 Robert A. Rucker 1 Mysteries of the Shroud • Image – Why can we see the image? – How was the image formed? • Date – What is the date of the Shroud? – What about the C14 dating? • Blood – How did it get onto the Shroud? – Why is it still reddish? 2 www.shroudresearch.net • On the RESEARCH page: • Paper 5: “Information Content on the Shroud of Turin” • Paper 6: “Role of Radiation in Image Formation on the Shroud of Turin” • Paper 22: “Image Formation on the Shroud of Turin” 3 Components of Reality • Mass • Space • Time • Energy • Information – We live in the information age. 4 CAD/CAM • CAD = computer aided design • CAM = computer aided machining • 3 requirements for CAD/CAM – equipment / mechanism – energy – information 5 CAD/CAM • What information? • The information that defines the design. 6 Computer Aided Design • The design is information 7 Computer Aided Machining • Mechanism + energy + information 8 Examples of Information 1. She saw a black cat. 2. Hes wsa a calbk tac. 3. Bcs ask l ahate awc. 4. bc saSk la h.ate awc 5. ░░ ░░░░ ░░ ░░░░░ ░░░ 6. There is information in the location of the dots / pixels 9 Every image is due to Information • Newspaper • Magazine • Photograph • TV • Computer Monitor • Image on the Shroud of Turin 10 To Form Any Image • Three Requirements – Mechanism – Energy – Information • What information? – That which defines the image 11 Image on a Photograph The information that defines her appearance is encoded into the location of the pixels that form the image. -

6Th ICCN INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on CLINICAL NEONATOLOGY 22-24 September 2016 Centro Congressi Unione Industriale Torino - Turin

6th ICCN INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CLINICAL NEONATOLOGY 22-24 September 2016 Centro Congressi Unione Industriale Torino - Turin RATIONAL/AIM: The Division of Neonatology and NICU of Sant’Anna Hospital in affiliation with the “Crescere Insieme al Sant’Anna” Scientific and Research Neonatology Foundation is proud to announce the 6th edition of the “International Conference on Clinical Neonatology”, which will be held in Torino, Italy from the 22nd to the 24th of September 2016. In line with the spirit of the previous successful editions, held in November 2009, March 2010, May 2012, June 2013 and September 2014 the goal of this Conference is to present the latest, updated scientific evidence on the care, treatment and follow-up of preterm neonates. Once more, the congress will be a multidisciplinary program of neonatal and perinatal research and practice, giving the opportunity to interact and share clinical and research experiences with colleagues in the Neonatology community. Prominent international speakers from all the fields of Neonatology and Pediatrics will provide comprehensive, up-to-date, research-based answers to the most frequent questions that arise at patient’s bedside in everyday practice. TOPICS: ECMO: Indications, risks and benefits Nutrition of preterm infants NIDCAP and family-centered care Respiratory viral infections in neonates and infants Kidney and the neonate BPD and lung injury in the preterm infant Pulmonary hypertension in term and preterm neonates Bioactive substances and their role in the preterm neonate NEC: an update To close or not to close: how to survive with an open PDA Late pulmonary function in preterm infants Optimal enteral feeding of premature infants Steroids in neonatology – an update “Omics” in neonatology Oximetry in the NICU Multi resistant organisms: challenges and solutions Laboratory at bedside: what’s new in the NICU? Less surfactant and less intubation: has this policy improved the outcomes? GENERAL INFORMATION Prof. -

Joint Evaluation of Joint Programmes on Gender Equality in the United Nations System

THEMATIC EVALUATION JOINT EVALUATION OF JOINT PROGRAMMES ON GENDER EQUALITY IN THE UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Final Synthesis Report – Annexes and Appendix November 2013 in partnership with ©2013 UN Women. All rights reserved. Acknowledgements Evaluation Team: A number of people contributed to this report. The evaluation was conducted by IOD PARC, an external and IOD PARC Julia Betts, Team Leader independent evaluation firm and expresses their views. Cathy Gaynor, Senior Gender and Evaluation Expert The evaluation process was managed by an Evaluation Angelica Arbulu, Gender Specialist Management Group that was chaired by the United Hope Kabuchu, Gender Specialist Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment Hatty Dinsmore, Research Support of Women (UN Women) and composed of representa- Laura McCall, Research Support tives from the independent evaluation offices of the Judith Friedman, Research Support commissioning entities - United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Children’s Fund Evaluation Management Group: (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), UN Women and the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund Shravanti Reddy (MDG-F) in partnership with the Governments of Spain and Belen Sanz Norway. Marco Segone Isabel Suarez The evaluation also benefitted from the active participation Chelsey Wickmark of reference groups. A global reference group was composed of United Nations staff with expertise in gender equality UNICEF and women empowerment, joint programmes, and United Colin Kirk Nations -

THE SHROUD of TURIN Its Implications for Faith and Theology

I4o THEOLOGICAL TRENDS THE SHROUD OF TURIN Its implications for faith and theology ACK IN I967, a notable Anglican exegete, C; F. D. Moule, registered a B complaint about some of his contemporaries: 'I have met otherwise intelligent men who ask, apparently in all seriousness, whether there may not be truth in what I would call patently ridiculous legends about.., an early portrait of Jesus or the shroud in which he is supposed to have been buried'. 1 Through the 195os into the 196os many roman Catholics, if they had come across it, would have agreed with Moule's verdict. That work of fourteen volumes on theology and church history, which Karl Rahner and other German scholars prepared, Lexikon fiir Theologie un d Kirehe (i957-68), simply ignored the shroud of Turin, except for a brief reference in an article on Ulysse Chevalier (1841-1923). Among his other achievements, the latter had gathered 'weighty arguments' to disprove the authenticity of the shroud. Like his english jesuit contemporary, Herbert Thurston, Chevalier maintained that it was a fourteenth-century forgery. The classic Protestant theological dictionary, Die Religion in Gesehichte und Gegenwart, however, took a different view. The sixth volume of the revised, third edition, which appeared in 1962 , included an article on the shroud by H.-M. Decker-Hauff. ~ The author summarized some of the major reasons in favour of its authenticity. In its material and pattern, the shroud matches products from the Middle East in the first century of the christian era. In the mid-fourteenth century the prevailing conventions of church art would not have allowed a forger or anyone else to portray Jesus in the full nakedness that we see on the shroud. -

Kutlug Ataman

KUTLUG ATAMAN Born: Istanbul, Turkey, 1961 Lives: Buenos Aires, Argentina, London, England and Istanbul, Turkey Education 1988 University of California, Los Angeles, MFA in Film 1985 University of California, Los Angeles, BA in Film 1983 Santa Monica College, Associate in Arts, Liberal Arts Selected Solo Exhibitions 2009 Solo, Ludwig Museum, Ludwig, Germany Mesopotamian Dramaturgies, Lentos Museum, Linz, Austria fff, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK 2008 Paradise and Küba, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, British Columbia. Paradise, Harris Museum & Art Gallery, Preston, England Küba, Tanas Berlin 2007 Art Basel Art Unlimited, Basel, Switzerland Paradise, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, California. Exhibition travels to BAK, Basis voor Actuele Kunst, Utrecht, The Netherlands Küba, Civic Centre, Southampton, UK 2006 Küba: Journey Against the Current, organized by Thyssen- Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna, Austria. Exhibition travels to 13 destinations along the Danube * Küba, Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, England DeRegulation with the Work of Kutlug Ataman, Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Antwerp, Belgium. Exhibition travels to Herzliya Museum of Art, Herzliya, Israel Küba, Extra City, Antwerp, Belgium Sherman Galleries, Syndey, Australia 2005 Küba, Artangel, London* Küba, Theater der Welt, Stuttgart, Germany Perfect Strangers, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia* Stefan’s Room, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago 2004 Stefan’s Room, Lehmann Maupin, New York 2003 Long Streams, Serpentine Gallery, London Long Streams, GEM, Museum voor Aktuele Kunst, The Hague 2002 Never My Soul! Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York Long Streams, Nikolaj, Copenhagen, Denmark* Women Who Wear Wigs, Istanbul Contemporary Arts Museum A Rose Blooms in the Garden of Sorrows, BAWAG Foundation, Vienna, Austria* Context: Europe 2002 – Impulses from South-Eastern Europe, Theater Des Augenblicks, Vienna. -

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Why Is the Turin Shroud Authentic?

Short Communication Glob J Arch & Anthropol Volume 7 Issue 2 - November 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Giulio Fanti DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.07.555707 Why is the Turin Shroud Authentic? Giulio Fanti* Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Padua, Italy Submission: October 04, 2018; Published: November 05, 2018 *Corresponding author: Giulio Fanti, Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Padua, Via Venezia 1 - 35131Padova, Italy. What is the Shroud The Shroud of Turin [1-7], the Holy Shroud or simply the Shroud (Figure 1) is the archaeological object, as well as religious, find proofs of authenticity even by using facts that are not strictly non-believers [6], on the other hand, seem sometimes blind to more studied in the world. It is in fact the only Relic that boasts scientific and sometimes connected to phenomena of pareidolia; but also hundreds of books in dozens of different languages; you scientific evidence that is not in accordance with their beliefs. not only dozens of publications in specialized scientific journals, cannot count the articles and notes that come out almost daily in the problem, avoiding the possible interference of other kinds, Here we will try to consider only the scientific aspects of the newspapers and on the web. especially religious, even to try to dampen the controversy that has emerged in recent times on this subject. Since many topics are very complex, we reserve the right to investigate any points of interest in possible subsequent interventions. The Authenticity of the Shroud Very frequently, there is also a heated discussion about the authenticity of the Shroud, without however clarifying what is the subject of the discussion, or what is meant by authenticity. -

Forensic Aspects and Blood Chemistry of the Turin Shroud Man

Scientific Research and Essays Vol. 7(29), pp. 2513-2525, 30 July, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/SRE DOI: 10.5897/SRE12.385 ISSN 1992 - 2248 ©2012 Academic Journals Review Forensic aspects and blood chemistry of the Turin Shroud Man Niels Svensson* and Thibault Heimburger 1Kalvemosevej 4, 4930 Maribo, Denmark. 215 rue des Ursulines, 93200 Saint-Denis, France. Accepted 12 July, 2012 On the Turin Shroud (TS) is depicted a faint double image of a naked man who has suffered a violent death. The image seems to be that of a real human body. Additionally, red stains of different size, form and density are spread all over the body image and in a few instances outside the body. Forensic examination by help of different analyzing tools reveals these stains as human blood. The distribution and flow of the blood, the position of the body are compatible with the fact that the Turin Shroud Man (TSM) has been crucified. This paper analyses the already known essential forensic findings supplied by new findings and experiments by the authors. Compared to the rather minute gospel description of the Passion of the Christ, then, from a forensic point of view, no findings speak against the hypothesis that the TS once has enveloped the body of the historical Jesus. Key words: Blood chemistry, crucifixion, forensic studies, Turin Shroud. INTRODUCTION The interest of the forensic examiners for the Turin Edwards et al.,1986; Zugibe, 2005). The TSM imprint is Shroud Man (TSM) image began with Paul Vignon and made of two different kinds of features: Yves Delage at the very beginning of the 20th century, after the remarkable discovery of the “negative” charac- i) The image itself, which has most of the properties of a teristics of the Turin Shroud (TS) image allowed by the negative “photography” and, as such, is best seen on the first photography of the TS by Secondo Pia in 1898. -

Index to Wrapped up in the Shroud by Joseph Marino Compiled by Paul C

1 J. G. Marino, Wrapped Up in Shroud, Index Index to Wrapped Up In the Shroud by Joseph Marino Compiled by Paul C. Maloney (July 2014) Note: There are 3 possible reasons for enclosing items in brackets in the following listing: 1. That Items (numbers) in brackets [ ] are there by inference—that is, the actual name may not appear on the designated page but that from the context it is obvious to whom or to what the reference is made. 2. The name never appears anywhere in the book but that the compiler has supplied it for the benefit of historians and other researchers. 3. Extended or expanded comments in brackets are made by the compiler. Items in quotes are usually the names of books, newspapers, or journals. Occasionally, such quote-marked items refer to quotes on a page. Occasionally, a topical word is used in the entry, but the topic may appear on a page with a different description. Users of this compilation may need to study the page to discover what the entry refers to. Abreviations: R in front of a page number = “References.” (Eg. “R205” = “References, p. 205). “A” in front of another alphabetic letter = “Appendix.” (Eg. “AA” = Appendix A, “AB” = “Appendix B,” etc.). If a name is also accompanied by “et al” I have not included the additional names in this compilation. The user may consult the References to look up the original article cited for the additional names who are co-authors of the article. I have tried to introduce cross referencing where appropriate. Such cross referencing may be incomplete. -

Likkledet I Torino: Hvem Støttet/Støtter C-14-Dateringen

Publisert 04.09.2018 LIKKLEDET I TORINO: HVEM STØTTET/STØTTER C-14-DATERINGEN Listen nedenfor er en liste over bøker, artikler og vitenskapelige artikler om Likkledet i Torino. Den er på ingen måte fullstendig, men er samlet over lang tid. Lista er satt opp for å vise hvor få forfattere om emnet som egentlig støtter riktigheten av C14- prøven fra 1988. Jeg viser til min egen bok om emnet, som kom i september 2018. Tittelen på den er: Likkledet i Torino: C14-dateringen 1988: Hva skjedde? Ikke alle artiklene handler om C14-prøven, selvsagt. En hjelp om dette kan være at tittelen jo avslører emnet, vanligvis. Som regel har bøkene med et kapittel eller to om C14-prøven og så godt som alltid svært negativt. Som du ser, er hvert oppsett forsynt med et nummer. Det er for lettere å kunne henvise til dem i annen sammenheng. De bøkene/forfatterne som støtter C14-prøven, er satt opp med RØDT. Av Jostein Andreassen A1= Adler, Alan D. & Whanger, Alan and Mary: Concerning the Side Strip on the Shroud of Turin (1997). ARTIKKEL. 6 sider. Omtaler C-14-dateringen. https://www.shroud.com/adler2.htm LIKKLEDET I TORINO: HVEM STØTTET/STØTTER C-14-DATERINGEN Side 1 av 1 A2= Adler, Alan D. & Piczek, Dame Isabel (eds.) & Minor, Michael (compiler): The Shroud of Turin. Unravelling the Mystery. In: Proceedings of the 1998 Dallas Symposium (2002). BOK; artikkelsamling av mange forfattere. A3= Ancient Origins (Magasin: nettside; forfatter ikke oppgitt): The Shroud of Turin: Controversial Cloth Defies Explanation as Study Shows it Has DNA From Around the World (2015).