Dancing Between Two Worlds- An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service

Responses of Plant Communities to Grazing in the Southwestern United States Department of Agriculture United States Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Daniel G. Milchunas General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-169 April 2006 Milchunas, Daniel G. 2006. Responses of plant communities to grazing in the southwestern United States. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-169. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 126 p. Abstract Grazing by wild and domestic mammals can have small to large effects on plant communities, depend- ing on characteristics of the particular community and of the type and intensity of grazing. The broad objective of this report was to extensively review literature on the effects of grazing on 25 plant commu- nities of the southwestern U.S. in terms of plant species composition, aboveground primary productiv- ity, and root and soil attributes. Livestock grazing management and grazing systems are assessed, as are effects of small and large native mammals and feral species, when data are available. Emphasis is placed on the evolutionary history of grazing and productivity of the particular communities as deter- minants of response. After reviewing available studies for each community type, we compare changes in species composition with grazing among community types. Comparisons are also made between southwestern communities with a relatively short history of grazing and communities of the adjacent Great Plains with a long evolutionary history of grazing. Evidence for grazing as a factor in shifts from grasslands to shrublands is considered. An appendix outlines a new community classification system, which is followed in describing grazing impacts in prior sections. -

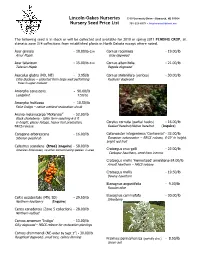

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Native Trees & Shrubs for Nebraska

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications Nebraska Statewide Arboretum 2011 NATIVE TREES & SHRUBS FOR NEBRASKA Justin R. Evertson University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Bob Henrickson Nebraska Statewide Arboretum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arboretumpubs Part of the Forest Biology Commons, and the Other Plant Sciences Commons Evertson, Justin R. and Henrickson, Bob, "NATIVE TREES & SHRUBS FOR NEBRASKA" (2011). Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications. 4. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arboretumpubs/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE TREES & SHRUBS FOR NEBRASKA Justin Evertson & Bob Henrickson, NSA 2011. For more plant information, visit arboretum.unl.edu or retreenbraska.unl.edu. Native plants withstand Nebraska’s tough climate extremes and serve as vital habitat for wildlife like birds, butterflies, and bees. NOTE: “Nearly native” signifies a species that is native within 100 miles of Nebraska’s border and/or now naturalized within the state. Common Native Trees Native Shrubby Trees 1. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 43. Amelanchier arborea - shadblow serviceberry (juneberry) 2. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 44. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 3. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 45. Prunus americana - American (wild) plum 4. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 46. Prunus mexicana - big-tree (Mexican) plum 5. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 47. Prunus virginiana - chokecherry 6. -

Botanical Name Common Name

Approved Approved & as a eligible to Not eligible to Approved as Frontage fulfill other fulfill other Type of plant a Street Tree Tree standards standards Heritage Tree Tree Heritage Species Botanical Name Common name Native Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes White Forsytha; Korean Abeliophyllum distichum Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Abelialeaf Acanthropanax Fiveleaf Aralia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes sieboldianus Acer ginnala Amur Maple Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus parviflora Bottlebrush Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Alnus incana ssp. rugosa Speckled Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Alnus serrulata Hazel Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier humilis Low Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier stolonifera Running Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes False Indigo Bush; Amorpha fruticosa Desert False Indigo; Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No No Not eligible Bastard Indigo Aronia arbutifolia Red Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia melanocarpa Black Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia prunifolia Purple Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Groundsel-Bush; Eastern Baccharis halimifolia Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Baccharis Summer Cypress; Bassia scoparia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Burning-Bush Berberis canadensis American Barberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Common Barberry; Berberis vulgaris Shrub, Deciduous No No No No Not eligible European Barberry Betula pumila -

OLFS Plant List

Checklist of Vascular Plants of Oak Lake Field Station Compiled by Gary E. Larson, Department of Natural Resource Management Trees/shrubs/woody vines Aceraceae Boxelder Acer negundo Anacardiaceae Smooth sumac Rhus glabra Rydberg poison ivy Toxicodendron rydbergii Caprifoliaceae Tatarian hone ysuckle Lonicera tatarica* Elderberry Sambucus canadensis Western snowberry Symphoricarpos occidentalis Celastraceae American bittersweet Celastrus scandens Cornaceae Redosier dogwood Cornus sericea Cupressaceae Eastern red cedar Juniperus virginiana Elaeagnaceae Russian olive Elaeagnus angustifolia* Buffaloberry Shepherdia argentea* Fabaceae Leadplant Amorpha canescens False indigo Amorpha fruticosa Siberian peashrub Caragana arborescens* Honey locust Gleditsia triacanthos* Fagaceae Bur oak Quercus macrocarpa Grossulariaceae Black currant Ribes americanum Missouri gooseberry Ribes missouriense Hippocastanaceae Ohio buckeye Aesculus glabra* Oleaceae Green ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica Pinaceae Norway spruce Picea abies* White spruce Picea glauca* Ponderosa pine Pinus ponderosa* Rhamnaceae Common buckthorn Rhamnus cathartica* Rosaceae Serviceberry Amelanchier alnifolia Wild plum Prunus americana Hawthorn Crataegus succulenta Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Siberian crab Pyrus baccata* Prairie rose Rosa arkansana Black raspberry Rubus occidentalis Salicaceae Cottonwood Populus deltoides Balm-of-Gilead Populus X jackii* White willow Salix alba* Peachleaf willow Salix amygdaloides Sandbar willow Salix exigua Solanaceae Matrimony vine Lycium barbarum* Ulmaceae -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al. -

Managing Intermountain Rangelands

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. USE OF ROSACEOUS SHRUBS FOR WILDLAND PLANTINGS IN THE INTERMOUNTAIN WEST Robert B. Ferguson ABSTRACT: This paper summarizes information on While many of the early efforts to use shrub Rosaceous shrubs to assist range or wildlife species in artificial revegetation centered on managers in planning range improvement projects. bitterbrush, other members of the Rosaceae were Species from at least 16 different genera of the being studied and recommended. Plummer and Rosaceae family have been used, or are others (1968) listed species that could be used potentially useful, for revegetating disturbed in revegetation programs in Utah, including true wildlands in the Intermountain West. mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus Raf.), Information is given on form and rate of growth, curlleaf mountain mahogany (C. ledifolius reproduction, longevity, and geographical Nutt.), cliffrose (Cowania mexicana var. distribution of useful Rosaceous shrubs. stansburiana [Torr.] Jeps.), desert bitterbrush Information is also presented on forage value, (Purshia glandulosa Curran), Saskatoon response to fire and herbicides, and the effects serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt.), Utah of insects and disease. Finally, methods used serviceberry (A. utahensis Koehne), Woods rose for the establishment of the Rosaceous shrubs (Rosa woodsii Lindl.), apache plume (Fallugia are described. paradoxa·[D. Don] Endl.), black chokecherry (Prunus virginiana L. var. melanocarpa [A. Nels.] Sarg.), desert peachbrush (P. fasciculata INTRODUCTION [Torr.] Gray), American plum (P. americana Marsh), squawapple (Peraphyllum ramosissimum William A. Dayton (1931), early plant ecologist Nutt.), and bush cinquefoil (Potentilla of the Forest Service, stated, "The rose group fruticosa L.). -

And Natural Community Restoration

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LANDSCAPING AND NATURAL COMMUNITY RESTORATION Natural Heritage Conservation Program Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707 August 2016, PUB-NH-936 Visit us online at dnr.wi.gov search “ER” Table of Contents Title ..……………………………………………………….……......………..… 1 Southern Forests on Dry Soils ...................................................... 22 - 24 Table of Contents ...……………………………………….….....………...….. 2 Core Species .............................................................................. 22 Background and How to Use the Plant Lists ………….……..………….….. 3 Satellite Species ......................................................................... 23 Plant List and Natural Community Descriptions .…………...…………….... 4 Shrub and Additional Satellite Species ....................................... 24 Glossary ..................................................................................................... 5 Tree Species ............................................................................... 24 Key to Symbols, Soil Texture and Moisture Figures .................................. 6 Northern Forests on Rich Soils ..................................................... 25 - 27 Prairies on Rich Soils ………………………………….…..….……....... 7 - 9 Core Species .............................................................................. 25 Core Species ...……………………………….…..…….………........ 7 Satellite Species ......................................................................... 26 Satellite Species -

Additions to the New Flora of Vermont

Gilman, A.V. Additions to the New Flora of Vermont. Phytoneuron 2016-19: 1–16. Published 3 March 2016. ISSN 2153 733X ADDITIONS TO THE NEW FLORA OF VERMONT ARTHUR V. GILMAN Gilman & Briggs Environmental 1 Conti Circle, Suite 5, Barre, Vermont 05641 [email protected] ABSTRACT Twenty-two species of vascular plants are reported for the state of Vermont, additional to those reported in the recently published New Flora of Vermont. These are Agrimonia parviflora, Althaea officinalis , Aralia elata , Beckmannia syzigachne , Bidens polylepis , Botrychium spathulatum, Carex panicea , Carex rostrata, Eutrochium fistulosum , Ficaria verna, Hypopitys lanuginosa, Juncus conglomeratus, Juncus diffusissimus, Linum striatum, Lipandra polysperma , Matricaria chamomilla, Nabalus racemosus, Pachysandra terminalis, Parthenocissus tricuspidata , Ranunculus auricomus , Rosa arkansana , and Rudbeckia sullivantii. Also new are three varieties: Crataegus irrasa var. irrasa , Crataegus pruinosa var. parvula , and Viola sagittata var. sagittata . Three species that have been reported elsewhere in 2013–2015, Isoetes viridimontana, Naias canadensis , and Solidago brendiae , are also recapitulated. This report and the recently published New Flora of Vermont (Gilman 2015) together summarize knowledge of the vascular flora of Vermont as of this date. The New Flora of Vermont was recently published by The New York Botanical Garden Press (Gilman 2015). It is the first complete accounting of the vascular flora of Vermont since 1969 (Seymour 1969) and adds more than 200 taxa to the then-known flora of the state. However, the manuscript for the New Flora was finalized in spring 2013 and additional species are now known: those that have been observed more recently, that have been recently encountered (or re-discovered) in herbaria, or that were not included because they were under study at the time of finalization. -

Native Plant Lists for Deer Lake Maple Forest Medium Sandy to Silt Loam Soils Less Than 4 Hours Sun Common Name Scientific Name Height Flower Color Groundcover

Native Plant Lists for Deer Lake Maple Forest Medium sandy to silt loam soils Less than 4 hours sun Common Name Scientific Name Height Flower Color Groundcover Cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea 2-5' NA False solomon seal Smilacina racemosa 18-24" NA Lady fern Athyrium felix-femina 18-24" NA Maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum 3-4' NA Meadow rue Thalictrum dioicum 8-28" Green Ostrich fern Matteuccia struthiopteris 3-4' NA Pennsylvania sedge Carex pensylvanica 6-18" NA Red baneberry Actaea rubra 1-2' White Sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis 1' NA White baneberry Actaea pachypoda 1-2' White Flowers Bellwort Uvularia grandiflora 1' Yellow Bloodroot Sanguinaria canadensis 2-6" White Columbine Aquilequia canadense 8-24" Pink False lily of the valley Maianthemum canadense 3-6" White False solomon's seal Smilacina stellata 8-24" White Jack-in-the-pulpit Arisaema triphyllum 1-3' Green Jacob's ladder Polemonium reptans 8-24" Blue Sessile-leaved bellwort Uvularia sessilifolia 10" Yellow Trillium Trillium grandiflorum 1' White Wild geranium Geranium maculatum 1-2' Lavender Wild ginger Asarum canadense 4-8" Red Woodland strawberry Fragaria vesca 4-6" White Shrubs Bush honeysuckle Diervilla lonicera 2-3' Yellow Common chokecherry Prunus virginiana to 20' White Ironwood Carpinus caroliniana to 30' NA Red-berried elder Sambucus pubens to 6' White Serviceberry/Juneberry Amelanchier laevis 10-12' White Trees Balsam fir Abies balsamea to 60' NA Black cherry Prunus serotina 80' NA Red maple Acer rubrum to 90' NA NA = Not Applicable, Sugar maple Acer saccharum -

Fresh Floral Resource Guide Seasonal Floral

Fresh Floral RESOURCE GUIDE SEASONAL FLORAL Everyday Spring Summer Fall Winter Alstroemeria Agapanthus Agapanthus Autumn Leaves Amaryllis Anthurium Amaryllis Amaranthus Chrysanthemum Anemone Aster Anemone Astilbe Dahlia Evergreen Bells of Ireland Cherry Blossom Cosmos Heather Heather Bupleurum Daffodil Dahlia Nerine Lily Muscari Calla Lily Dogwood Daisy Ranunculus Nerine Lily Carnation Forsythia Delphinium Seasonal Berries Poinsettia Craspedia Heather Garden Rose Sunflower Ranunculus Eryngium Hyacinth Gladiolus Tuberose Tulip Fiddlehead Fern Lilac Lady Mantle Waxflower Freesia Lily of the Valley Larkspur Gardenia Muscari Nerine Lily Gerbera Nerine Lily Scabiosa Gloriosa Lily Peony Snapdragon Hydrangea Ranunculus Tuberose Hypericum Sweet Pea Violet Iris Tuberose Zinnia Kermit’ Pompom Tulip Liatris Viburnum Lily Waxflower Limonium Lisianthus Lotus Pod Orchird Ornithogalum Arabicum Queen Anne’s Lace Rose Solidago Solidaster Spider Gerbera Statice Stephanotis Stock Trachelium Viking Mini Pompom BloomNet Fresh Floral Resource Guide 1 CARE & HANDLING Alstroemeria Alstroemeria is extremely ethylene sensitive. Remove any foliage that will go below the water line, as it deteriorates quickly. Then cut stems and place in a vase with room temperature water and floral food. Category: Basic Color: Yellow, Orange, White, Pink, Red, Lavender, Purple, Magenta, Peach, Bi Color Amaryllis Do not store amaryllis at below 41 degrees as this may discolor blooms. Amaryllis flowers damage very easily in bud or bloom stage. Allow space around the blooms in a bucket or design to prohibit damage. Category: Novelty Color: White, Pink, Red, Peach, Orange, Bi Color Anthurium An extremely long lasting Tropical flower with a vase life from 15 to 30 days (mini and small grades tend to have a shorter vase life).