From Dear Esther to Inchcolm Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

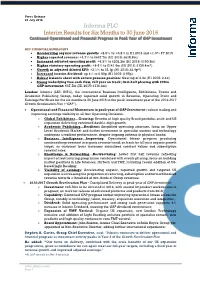

Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP Investment

Press Release 28 July 2016 Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP investment KEY FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Accelerating organic revenue growth: +2.5% vs +0.2% in H1 2015 and +1.0% FY 2015 Higher reported revenue: +4.7% to £647.7m (H1 2015: £618.8m) Increased adjusted operating profit: +6.3% to £202.2m (H1 2015: £190.3m) Higher statutory operating profit: +8.6% to £141.6m (H1 2015: £130.4m*) Growth in adjusted diluted EPS: +3.1% to 23.1p (H1 2015: 22.4p*) Increased interim dividend: up 4% to 6.80p (H1 2015: 6.55p) Robust balance sheet with secure pension position: Gearing of 2.4x (H1 2015: 2.4x) Strong underlying free cash flow, full year on track; first-half phasing with £20m GAP investment: £67.7m (H1 2015: £116.4m) London: Informa (LSE: INF.L), the international Business Intelligence, Exhibitions, Events and Academic Publishing Group, today reported solid growth in Revenue, Operating Profit and Earnings Per Share for the six months to 30 June 2016 in the peak investment year of the 2014-2017 Growth Acceleration Plan (“GAP”). Operational and Financial Momentum in peak year of GAP Investment – robust trading and improving earnings visibility in all four Operating Divisions: o Global Exhibitions…Growing: Benefits of high quality Brand portfolio, scale and US expansion delivering continued double-digit growth; o Academic Publishing…Resilient: Simplified operating structure, focus on Upper Level Academic Market and further investment in specialist content -

A Theoretical Framework of Ludic Knowledge: a Case Study in Disruption and Cognitive Engagement Peter Howell University of Portsmouth

The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Malta 2016 A Theoretical Framework of Ludic Knowledge: A Case Study in Disruption and Cognitive Engagement Peter Howell University of Portsmouth Abstract This paper presents a theoretical framework of ludic knowledge applicable to game design. It was developed as a basis for disrupting player knowledge of ‘normative’ game rules and behaviours, stored as different types of ludic knowledge (intraludic, interludic, transludic, and extraludic), with the aim of supporting a player’s cognitive engagement with a game. The framework describes these different types of knowledge and how they inform player expectation, engagement with gameplay choices, and critical responses to games before, during, and after play. Following the work by Howell, Stevens, and Eyles (2014) that presented an initial schema-based framework of player learning during gameplay, this paper further develops the framework based on its application to the design and development of the commercial game Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs (The Chinese Room, 2013); a first-person horror- adventure title released for PC. While the theoretical framework of ludic knowledge was developed to support the concept of ‘disruption’, it can also be applied as a standalone tool usable as a basis for critical analysis of how players engage with and talk about games more generally. The Foundation of a Theoretical Framework of Ludic Knowledge Knowledge as it relates to any one particular game has been previously suggested to be separable into three categories (Howell, Stevens, and Eyles, 2014), based on how that knowledge is contextualised relative to that particular game. Intraludic knowledge relates to the particular game being played, transludic knowledge relates to multiple other games that an individual may have played in the past, and extraludic knowledge relates to any life experiences outside of playing games. -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

Annual Report & Accounts 2020

Sumo Group Annual Report & Accounts 2020 Sumo Report & Accounts Annual Group sumogroupplc.com Annual Report & Accounts 2020 We are one of the UK’s largest providers of end-to-end creative development and co-development services to the video games and entertainment industries. We make highly innovative games for the most prestigious publishers in the world, with an increasing number of titles based on original concepts developed by Sumo. Strategic Report Governance Financial Statements At a Glance 2 Introduction to Governance 45 Independent Auditor’s report 68 Chairman’s Statement 4 Corporate Governance 46 Consolidated Income Statement 76 Business Model 6 Board of Directors 50 Consolidated Statement of Our Businesses 14 Operating Board 52 Comprehensive Income 77 Our Markets 20 Audit and Risk Committee Report 54 Consolidated Balance Sheet 78 Our Strategy 22 Directors’ Remuneration Report 56 Consolidated Statement of Chief Executive’s review 23 Directors’ Report 64 Changes in Equity 79 Group Financial Review 29 Statement of Directors’ Consolidated Cash Flow Section 172 Statement 34 Responsibilities 66 Statement 80 Environmental, Social Notes to the Group Financial and Governance 38 Statements 81 Energy and Carbon Report 40 Parent Company Balance Sheet 114 Risks & Uncertainties 41 Parent Company Statement of Changes in Equity 115 Notes to the Parent Company Financial Statements 116 Financial Calendar and Company Information 119-120 Designed and printed by Perivan STRATEGICSTRATEGIC REPORTREPORT Highlights Our vision Achieving wonder together. Revenue £68.9m 2019: £49.0m +40.7% Gross profit Our mission £31.5m 2019: £23.9m Grow a sustainable business, providing security to our +31.5% people and shareholders, whilst delivering a first-class experience to our partners and players. -

Patient Safety for Ellen Patient Safety

Patient Safety For Ellen Patient Safety Perspectives on Evidence, Information and Knowledge Transfer Edited by Lorri ZiPPerer © Lorri Zipperer 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Lorri Zipperer has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work. Published by Gower Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3-1 Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-3818 Surrey, GU9 7PT USA England www.gowerpublishing.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zipperer, Lorri A., 1959- Patient safety : perspectives on evidence, information and knowledge transfer / by Lorri Zipperer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-3857-1 (hbk) -- ISBN 978-1-4094-3858-8 (ebk) -- ISBN 978-1-4724-0243-1 (epub) 1. Hospital patients--Safety measures. 2. Medical errors--Prevention. I. Title. RA965.6.Z57 2014 610.28’9--dc23 2013028766 ISBN 978 1 4094 3857 1 (hbk) ISBN 978 1 4094 3858 8 (ebk – PDF) ISBN 978 1 4724 0243 1 (ebk – ePUB) III Contents List of Figures ix List of Tables xi About the Editor xiii About the Contributors xv Foreword xxix Preface xxxv List of Abbreviations xliii Acknowledgements xlv PART 1 CONTEXT FOR INNOVATION AND IMPROVEMENT Chapter 1 Patient Safety: A Brief but Spirited History 3 Robert L. -

SUMO FINAL RESULTS 2020 Sumo Group, T

31 March 2021 SUMO GROUP PLC (“Sumo Group”, the “Group” or the “Company”) AIM: SUMO FINAL RESULTS 2020 Sumo Group, the award-winning provider of creative and development services to the video games and entertainment industries, announces its final results for the year ended 31 December 2020 (“FY20”), which show substantial growth in revenue and Adjusted EBITDA and further outperform consensus market expectations for FY20, which were upgraded in January 2021 following the Group’s positive trading update. Financials Reported results 2020 2019 Change Revenue £68.9m £49.0m + 40.7% Gross profit £31.5m £23.9m + 31.5% Gross margin 45.7% 48.9% Profit before taxation1 £0.9m £7.4m Cash flow from operations £13.0m £14.4m Net cash £6.8m £12.9m Basic earnings per share 1.08p 5.19p Diluted earnings per share 1.01p 5.07p Underlying results 2020 2019 Change Adjusted gross profit2 £31.7m £25.2m + 25.8% Adjusted gross margin3 41.8% 44.8% Adjusted EBITDA4 £16.5m £14.1m + 17.1% 1 The statutory profit before taxation of £0.9m in 2020 is stated after charging an amount of £7.3m arising on the acquisition of Pipeworks consisting of the £2.7m fair value loss on contingent consideration, £1.7m of amortisation of customer contracts and customer relationships and £2.9m of transactions costs on that acquisition. In addition, the statutory profit before taxation is stated after charging exceptional items other than the costs incurred on the acquisition of Pipeworks of £1.2m (2019: £0.5m) and the share-based payment charge of £5.0m (2019: £2.7m) and the unrealised gain on foreign currency derivative contracts of £1.0m. -

Class 200: New Studies in Religion”

V NEWS n New Book Series: “Class 200: New Studies in Religion” The University of Chicago Press has recently launched a new book series: “Class 200: New Stud- ies in Religion.” The editors of the series are Kathryn Lofton (Department of Religious Studies, Yale University) and John Lardas Modern (Department of Religious Studies, Franklin & Mar- shall College). According to the editors, “Class 200 offers the most innovative works in the study of religion today. Resting on a generation of critical scholarship that reevaluated the central categories of the field, the series aims to surpass that good work by rebuilding the vocabulary of, and estab- lishing new questions for, religious studies. “The series will publish authors who understand descriptions of religion to be always bound up in explanations for it. It will nurture authorial reflexivity, documentary intensity, and gene- alogical responsibility. The series presumes no inaugurating definition of religion other than what it is not: it is not reducible to demographics, doctrines, or cognitive mechanics. It is more than a discursive concept or cultural idiom. It is something that can be named only with a pre- cise and poetic wrestling with the nature of its naming. “Class 200 seeks to renew the study of religion as a field of inquiry that is open in terms of disciplinary affiliation, relishes archival and ethnographic immersion, and is scrupulous in its use of categories. The series is not defined by topics but by certain shared fundamentals: rigor, an investment in language, an awareness of authority, and a strategy regarding the politics of truth claims in any archival or anthropological situation.” More information can be found at the University of Chicago Press’s website: http://www. -

I PERFORMING VIDEO GAMES: APPROACHING GAMES AS

i PERFORMING VIDEO GAMES: APPROACHING GAMES AS MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Remzi Yagiz Mungan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts August 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana ii to Selin iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I read that the acknowledgment page might be the most important page of a thesis and dissertation and I do agree. First, I would like to thank to my committee co‐chair, Prof. Fabian Winkler, whom welcomed me to ETB with open arms when I first asked him about the program more than three years ago. In these three years, I have learned a lot from him about art and life. Second, I want to express my gratitude to my committee co‐chair, Prof. Shannon McMullen, whom helped when I got lost and supported me when I got lost again. I will remember her care for the students when I teach. Third, I am thankful to my committee member Prof. Rick Thomas for having me along the ride to Prague, teaching many things about sound along the way and providing his insightful feedback. I was happy to be around a group of great people from many areas in Visual and Performing Arts. I specially want to thank the ETB people Jordan, Aaron, Paul, Mara, Oren, Esteban and Micah for spending time with me until night in FPRD. I also want to thank the Sound Design people Ryan, Mike and Ian for our time in the basement or dance studios of Pao Hall. -

Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality New Directions in Tourism Analysis Series Editor: Dimitri Ioannides, E-TOUR, Mid Sweden University, Sweden

SOCIAL MEDIA IN TRAVEL, TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY New Directions in Tourism Analysis Series Editor: Dimitri Ioannides, E-TOUR, Mid Sweden University, Sweden Although tourism is becoming increasingly popular as both a taught subject and an area for empirical investigation, the theoretical underpinnings of many approaches have tended to be eclectic and somewhat underdeveloped. However, recent developments indicate that the field of tourism studies is beginning to develop in a more theoretically informed manner, but this has not yet been matched by current publications. The aim of this series is to fill this gap with high quality monographs or edited collections that seek to develop tourism analysis at both theoretical and substantive levels using approaches which are broadly derived from allied social science disciplines such as Sociology, Social Anthropology, Human and Social Geography, and Cultural Studies. As tourism studies covers a wide range of activities and sub fields, certain areas such as Hospitality Management and Business, which are already well provided for, would be excluded. The series will therefore fill a gap in the current overall pattern of publication. Suggested themes to be covered by the series, either singly or in combination, include – consumption; cultural change; development; gender; globalisation; political economy; social theory; sustainability. Also in the series Tourists, Signs and the City The Semiotics of Culture in an Urban Landscape Michelle M. Metro-Roland ISBN 978-0-7546-7809-0 Stories of Practice: Tourism -

Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role-Playing Video Games

University of Huddersfield Repository Jennifer, Smith Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role Playing Video Games Original Citation Jennifer, Smith (2020) Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role Playing Video Games. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35389/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role-Playing Video Games Jennifer Caron Smith A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield October 2020 1 Copyright Statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/ or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. -

Impact Case Study (Ref3b) Institution: University of Portsmouth

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: University of Portsmouth Unit of Assessment: 36 Communication, Cultural and Media Studies; Library and Information Management Title of case study: Game Changing: Games research creates new knowledge of digital games environments, improves industry perception of collaborations with academia and results in commercially successful, award-winning products 1. Summary of the impact An innovative approach towards researching story-telling and its relevance in games design has resulted in cultural and economic impact in the creative sector and generated novel approaches that have influenced creative practice in the games industry. As a direct result of the research, an independent games development studio has been established and two commercial game titles have been released, with commercial sales to date of approximately £1.65m. The first release, Dear Esther, has been a major commercial success, has also won several industry recognition awards and is cited as directly responsible for the genesis of a new gaming genre. 2. Underpinning research The research described was led by Dr Dan Pinchbeck, Reader in Computer Games at the University of Portsmouth, School of Creative Technologies, between March 2007 and February 2013. Pinchbeck identified a lack of research data in the area of participant experience, narrative modes and games design. In 2007-8, he was awarded an AHRC speculative research grant [Grant 1] to lead research into how story telling in virtual environments could be used to increase participants’ sense of immersion and self-presence (1, 2). To create conditions under which player participation could be evaluated an innovative approach to the research was taken: to maximise the experiential engagement of players, virtual environments within games were created and made publicly available to the gaming community. -

Humanities Section (463KB)

UNIVERSITY OF SAN CARLOS Josef Baumgartner Learning Resource Center Humanities Section Acquisitions List FIRST SEMESTER, SY 2015 – 2016 THE ARTS Alread, Jason. (2014). Design-tech: building science for architects. 2nd edition. New York: Routledge. [720 Al77] Anderson, Kjell. (2014). Design energy simulation for architects: guide to 3D graphics. New York: Routledge. [720.472028566] Bailey, Sarah. (2014). Visual merchandising for fashion. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [746.920688 B15] Ballinger, Barbara. (2014). The kitchen bible: designing the perfect culinary space. Australia: Images Publishing. [747.797 B21] Barlis, Alan. (2013). Classic and modern: signature and styles. [San Rafael, California]: ORO Editions. [728 B24] Binggeli, Corky. (2014). Materials for interior environments. 2nd edition. Hoboken: Wiley. [729 B51] Bonda, Penny. (2014). Sustainable commercial interiors. 2nd edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [725.23047 B64] Bradbury, Dominic. (2014). New Brazilian house: with 303 colour illustrations. New York, N.Y.: Thames and Hudson. [720.0981 B72] Broto, Charles. (2014). Social housing: architecture and design. Barcelona: Links International. [728.1 B79] 1 Bluyssen, Philomena. (2014). The healthy indoor environment: how to assess occupants’ welllbeing in buildings. New York: Taylor & Francis Group. [720.286 B62] Burkhalter, Thomas. (2013). Local music scenes and globalization: transnational platforms in Beirut. New York: Routledge. [780.956925 B91] Cairns, Stephen. (2014). Buildings must die: a perverse view of architecture. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. [720.1 C12] Camuffo, Dario. (2014). Microclimate for cultural heritage: conservation, restoration, and maintenance of indoor and outdoor monuments . 2nd edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [702.9 C15] Cantor, Jeremy. (2014). Secrets of CG short filmmakers. Boston: Cengage Learning PTR. [777.7 C16] Cline, Lydia Sloan.