Cosplay Culture: the Development of Interactive and Living Art Through Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On-Site Historical Reenactment As Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation

Fall2002 107 Recreation and Re-Creation: On-Site Historical Reenactment as Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation Scott Magelssen Plimoth Plantation, a Massachusetts living history museum depicting the year 1627 in Plymouth Colony, advertises itself as a place where "history comes alive." The site uses costumed Pilgrims, who speak to visitors in a first-person presentvoice, in order to create a total living environment. Reenactment practices like this offer possibilities to teach history in a dynamic manner by immersing visitors in a space that allows them to suspend disbelief and encounter museum exhibits on an affective level. However, whether or not history actually "comes alive"at Plimoth Plantation needs to be addressed, especially in the face of new or postmodem historiography. No longer is it so simple to say the past can "come alive," given that in the last thirty years it has been shown that the "past" is contestable. A case in point, I argue, is the portrayal of Wampanoag Natives at Plimoth Plantation's "Hobbamock's Homesite." Here, the Native Wampanoag Interpretation Program refuses tojoin their Pilgrim counterparts in using first person interpretation, choosing instead to address visitors in their own voices. For the Native Interpreters, speaking in seventeenth-century voices would disallow presentationoftheir own accounts ofthe way colonists treated native peoples after 1627. Yet, from what I have learned in recent interviews with Plimoth's Public Relations Department, plans are underway to address the disparity in interpretive modes between the Pilgrim Village and Hobbamock's Homesite by introducing first person programming in the latter. I Coming from a theatre history and theory background, and looking back on three years of research at Plimoth and other living history museums, I would like to trouble this attempt to smooth over the differences between the two sites. -

Historical Reenactment in Photography: Familiarizing with the Otherness of the Past?

INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND FOLKLORE STUDIES WITH ETHNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM AT THE BULGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES The Multi-Mediatized Other The Construction of Reality in East-Central Europe, 1945–1980 EDITED BY DAGNOSŁAW DEMSKI ANELIA KASSABOVA ILDIKÓ SZ. KRISTÓF LIISI LAINESTE KAMILA BARANIECKA-OLSZEWSKA BUDAPEST 2017 Contents 9 Acknowledgements 11 Dagnosław Demski in cooperation with Anelia Kassabova, Ildikó Sz. Kristóf, Liisi Laineste and Kamila Baraniecka-Olszewska Within and Across the Media Borders 1. Mediating Reality: Reflections and Images 30 Dagnosław Demski Cultural Production of the Real Through Picturing Difference in the Polish Media: 1940s–1960s 64 Zbigniew Libera, Magdalena Sztandara Ethnographers’ Self-Depiction in the Photographs from the Field. The Example of Post-War Ethnology in Poland 94 Valentina Vaseva The Other Dead—the Image of the “Immortal” Communist Leaders in Media Propaganda 104 Ilkim Buke-Okyar The Arab Other in Turkish Political Cartoons, 1908–1939 2. Transmediality and Intermediality 128 Ildikó Sz. Kristóf (Multi-)Mediatized Indians in Socialist Hungary: Winnetou, Tokei-ihto, and Other Popular Heroes of the 1970s in East-Central Europe 156 Tomislav Oroz The Historical Other as a Contemporary Figure of Socialism—Renegotiating Images of the Past in Yugoslavia Through the Figure of Matija Gubec 178 Annemarie Sorescu-Marinković Multimedial Perception and Discursive Representation of the Others: Yugoslav Television in Communist Romania 198 Katya Lachowicz The Cultivation of Image in the Multimedial Landscape of the Polish Film Chronicle 214 Dominika Czarnecka Otherness in Representations of Polish Beauty Queens: From Miss Baltic Coast Pageants to Miss Polonia Contests in the 1950s 3. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: Sept 09, 2020 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] PLEASE DOUBLECHECK ALL EVENTS, THINGS ARE STILL BE POSTPONED OR CANCELLED. SOMETIMES FACEBOOK WILL SAY CANCELLED YET WEBSITE STILL SHOWS REGULAR EVENT! JUNE 12-14 PA SCI-FI VALLEY CON 2020 POSTPONED TO JUNE 18-20, 2021 SF/Fantasy media https://www.scifivalleycon.com/ JUNE 12-14 Pitt THE LIVING DEAD WEEKEND POSTPONED TO NOV 6-8, 2020 Horror! http://www.thelivingdeadweekend.com/monroeville/ JUNE 12-14 NJ ANIME NEXT 2020 CANCELLED anime/manga/cosplay http://www.animenext.org/ JUNE 13-14 RI THE TERROR CON POSTPONED, no date set horror con https://www.theterrorcon.com/ JUNE 19-21 Phil WIZARD WORLD CANCELLED will return in 2021 media/comics/cosplay https://wizardworld.com/comiccon/philadelphia JUNE 19-21 T.O. INT'L FAN FESTIVAL TORONTO POSTPONED, no new date yet anime/gaming/comics https://toronto.ifanfes.com/ JUNE 19-21 Pitt MONSTER BASH CONFERENCE CANCELLED, see October event horror film/tv fans https://www.monsterbashnews.com/bash-June.html JUNE 20-21 Cinn SCI-CON 2020 CANCELLED will return in 2021 media/science/cosplay http://www.ctspromotions.com/currentshow/ JUNE 20-21 IN RAPTOR CON POSTPONED to Dec 12-13, 2020 anime/geek/media https://lind172.wixsite.com/rustyraptor/ JUNE 27-28 Buf LIL CON 7 POSTPONED, no new date announced yet http://lilconconvention.com/ JUNE 28 Buf PUNK ROCK FLEA MARKET & GEEK GARAGE -

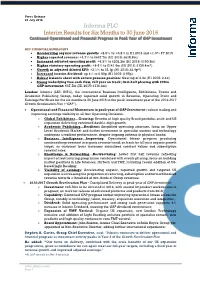

Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP Investment

Press Release 28 July 2016 Informa PLC Interim Results for Six Months to 30 June 2016 Continued Operational and Financial Progress in Peak Year of GAP investment KEY FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Accelerating organic revenue growth: +2.5% vs +0.2% in H1 2015 and +1.0% FY 2015 Higher reported revenue: +4.7% to £647.7m (H1 2015: £618.8m) Increased adjusted operating profit: +6.3% to £202.2m (H1 2015: £190.3m) Higher statutory operating profit: +8.6% to £141.6m (H1 2015: £130.4m*) Growth in adjusted diluted EPS: +3.1% to 23.1p (H1 2015: 22.4p*) Increased interim dividend: up 4% to 6.80p (H1 2015: 6.55p) Robust balance sheet with secure pension position: Gearing of 2.4x (H1 2015: 2.4x) Strong underlying free cash flow, full year on track; first-half phasing with £20m GAP investment: £67.7m (H1 2015: £116.4m) London: Informa (LSE: INF.L), the international Business Intelligence, Exhibitions, Events and Academic Publishing Group, today reported solid growth in Revenue, Operating Profit and Earnings Per Share for the six months to 30 June 2016 in the peak investment year of the 2014-2017 Growth Acceleration Plan (“GAP”). Operational and Financial Momentum in peak year of GAP Investment – robust trading and improving earnings visibility in all four Operating Divisions: o Global Exhibitions…Growing: Benefits of high quality Brand portfolio, scale and US expansion delivering continued double-digit growth; o Academic Publishing…Resilient: Simplified operating structure, focus on Upper Level Academic Market and further investment in specialist content -

The Atlanta Puppet Press

The Atlanta Puppet Press The N ew sletter o f the Atlanta Puppetry G uild C hartered b y the Puppeteers o f Am eric a April 20 0 5 W hat’s Insid e M eeting Inf o rm atio n Page 2....................Pawpet MegaPLEX When: Sunday, April 10th at 5 PM Page 4..............Guild Officer Elections Where: Lee Bryan’s House Page 5.....Adventures w/Puppet People 1314 LaVista Rd, NE Page 6............ Website / Online Corner Atlanta, GA 30357-2937 Page 7........ Puppetry News and Events Page 8........................Puppet Fest 2005 Directions: Page 9...................PofA / Puppet News From Cheshire Bridge Road (Tara Shopping Center), count Page 10................. Guild Photo Gallery six houses up on the left hand side. You will probably have Page 12...................... Meeting Minutes to park on the street just before (Citadel) and walk over Page 13.................... Guild Information since parking is limited. What’s Happening: Y o ur Id eas Are N eed ed ! • COVERED DISH SOCIAL – Lee is providing ice tea, soft drinks, plates, etc. The deck will be open, so bring a The Atlanta Puppet Press has the potential to picnic-style main dish or side dish or desert to share. become a great newsletter, but I can’t do it alone. You can help by submitting short • OFFICER ELECTIONS – A new guild president and puppetry related items that would be of treasurer will be elected. Now is your chance to become interest to other guild members. Here are just even more active in our guild! a few possible ideas: • NATIONAL DAY OF PUPPETRY PLANNING – We’ll News and Events How-To’s be finalizing our plans for our National Day activities at Book & Show Reviews Helpful Tips Centennial Olympic Park on Saturday, April 30th If you would like to be a regular columnist, • SHOW AND TELL – Bring in something fun and there are many topics that you can choose interesting to share with the group or tell the group about from. -

Carnegie Corporation of New York a N N U a L R E P O R T 2004-2005 Carnegie Corporation of New York

Carnegie Corporation of New York COMBINED ANNU A L R E P O R T 2004-2005 ANNU A L R E P O R T 2004-2005 Carnegie Corporation of New York Carnegie Corporation of New York was created by Andrew Carnegie in 1911 to promote “the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding.” Under Carnegie’s will, grants must benefit the people of the United States, although up to 7.4 percent of the funds may be used for the same purpose in countries that are or have been members of the British Commonwealth, with a current emphasis on sub-Saharan Africa. As a grantmaking foundation, the Corporation seeks to carry out Carnegie’s vision of philanthropy, which he said should aim “to do real and permanent good in this world.” © 2007 Carnegie Corporation of New York Contents REPORT OF THE PrESIDENT I Reflections on Encounters With Three Cultures 2004 REPORT ON PrOGRAM 1 Ongoing Evaluation Enhances the Corporation’s Grantmaking Strategies in 2004 Grants and Dissemination Awards Education International Development International Peace and Security Strengthening U.S. Democracy Special Opportunities Fund Carnegie Scholars Dissemination Anonymous $15 Million in Grants to Cultural and Social Service Institutions in New York City 2004 REPORT ON FINANCES 77 Financial Highlights 2004 REPORT ON ADMINISTRATION 91 Fiscal 2004: The Year in Review 2005 REPORT ON PrOGRAM 97 Key Programs Meet the Challenges of Maturity in 2005 Grants and Dissemination Awards Education International Development International Peace and Security Strengthening U.S. Democracy Special Opportunities -

Posthum/An/Ous: Identity, Imagination, and the Internet

POSTHUM/AN/OUS: IDENTITY, IMAGINATION, AND THE INTERNET A Thesis By ERIC STEPHEN ALTMAN Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2010 Department of English POSTHUM/AN/OUS: IDENTITY, IMAGINATION, AND THE INTERNET A Thesis By ERIC STEPHEN ALTMAN May 2010 APPROVED BY: ___________________________________________ Dr. James Ivory Chairperson, Thesis Committee ___________________________________________ Dr. Jill Ehnenn Member, Thesis Committee ___________________________________________ Dr. Thomas McLaughlin Member, Thesis Committee ___________________________________________ Dr. James Ivory Chairperson, Department of English ___________________________________________ Dr. Edelma Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Eric Altman 2010 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT POSTHUM/AN/OUS: IDENTITY, IMAGINATION, AND THE INTERNET (May 2010) Eric Stephen Altman, B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Thesis Chairperson: Dr. James Ivory The Furry, Otherkin, and Otakukin are Internet fan subcultures whose members personally identify with non-human beings, such as animals, creatures of fantasy, or cartoon characters. I analyze several different forms of expression that the fandoms utilize to define themselves against the human world. These are generally narrative in execution, and the conglomeration of these texts provides the communities with a concrete ontology. Through the implementation of fiction and narrative, the fandoms are able to create and sustain complex fictional personas in complex fictional worlds, and thereby create a “real” subculture in physical reality, based entirely off of fiction. Through the use of the mutability of Internet performance and presentation of self-hood, the groups are able to present themselves as possessing the traits of previous, non-human lives; on the Internet, the members are post-human. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: June 23, 2021 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] PLEASE DOUBLECHECK ALL EVENTS, THINGS ARE STILL BE POSTPONED OR CANCELLED. SOMETIMES FACEBOOK WILL SAY CANCELLED YET WEBSITE STILL SHOWS REGULAR EVENT! JUNE 24 NYC BIG APPLE COMIC CON-Summer Event New Yorker Htl, Manhatten, NY NY www.bigapplecc.com JUNE 25 Virt ANIME: NAUSICAA OF THE VALLEY OF THE WIND group watch event (requires Netflix account) https://www.fanexpocanada.com JUNE 25 Virt STAR WARS TRIVIA: ROGUE ONE round one features Rogue One movie trivia game https://www.fanexpocanada.com JUNE 25-27 S.F. CREATION - SUPERNATURAL Hyatt Regency Htl, San Francisco CA TV series tribute https://www.creationent.com/ JUNE 26-27 N.J. CREATION - STRANGER THINGS NJ Conv Ctr, Edison, NJ (NYC) TV series tribute https://www.creationent.com/ JUNE 27 Virt WIZARD WORLD-STAR TREK GUEST STARS Virtual event w/ cast some parts free, else to buy https://wizardworld.com/ Charlie Brill, Jeremey Roberts, John Rubenstein, Gary Frank, Diane Salinger, Kevin Brief JUNE 27 BTC BUFFALO TIME COUNCIL MEETING 49 Greenwood Pl, Buffalo monthly BTC meeting buffalotime council.org YES!! WE WILL HAVE A MEETING! JULY 8-11 MA READERCON Marriott Htl, Quincy, Mass (Boston) Books & Authors http://readercon.org/ Jeffrey Ford, Ursula Vernon, Vonda N McIntyre (in Memorial) JULY 9-11 T.O. TFCON DELAYED UNTIL DEC 10-12, 2021 Transformers fan-run -

Annual Copyright License for Corporations

Responsive Rights - Annual Copyright License for Corporations Publisher list Specific terms may apply to some publishers or works. Please refer to the Annual Copyright License search page at http://www.copyright.com/ to verify publisher participation and title coverage, as well as any applicable terms. Participating publishers include: Advance Central Services Advanstar Communications Inc. 1105 Media, Inc. Advantage Business Media 5m Publishing Advertising Educational Foundation A. M. Best Company AEGIS Publications LLC AACC International Aerospace Medical Associates AACE-Assn. for the Advancement of Computing in Education AFCHRON (African American Chronicles) AACECORP, Inc. African Studies Association AAIDD Agate Publishing Aavia Publishing, LLC Agence-France Presse ABC-CLIO Agricultural History Society ABDO Publishing Group AHC Media LLC Abingdon Press Ahmed Owolabi Adesanya Academy of General Dentistry Aidan Meehan Academy of Management (NY) Airforce Historical Foundation Academy Of Political Science Akademiai Kiado Access Intelligence Alan Guttmacher Institute ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Albany Law Review of Albany Law School Acta Ecologica Sinica Alcohol Research Documentation, Inc. Acta Oceanologica Sinica Algora Publishing ACTA Publications Allerton Press Inc. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae Allied Academies Inc. ACU Press Allied Media LLC Adenine Press Allured Business Media Adis Data Information Bv Allworth Press / Skyhorse Publishing Inc Administrative Science Quarterly AlphaMed Press 9/8/2015 AltaMira Press American -

Slave Dwelling Project Conference

FIFTH ANNUAL SLAVE DWELLING PROJECT CONFERENCE SLAVERY, RESISTANCE, AND COMMUNITY OCTOBER 24–27, 2018 MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY MURFREESBORO, TENNESSEE Info at slavedwellingproject.org Keynote Speaker Colson Whitehead is the New York Times No. 1 best-selling author of The Underground Railroad (winner of the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize), The Noble Hustle, Zone One, Sag Harbor, The Intuitionist, John Henry Days, Apex Hides the Hurt, and one collection of essays, The Colossus of New York. He was named New York’s state author in 2018, the 11th in history. Whitehead’s reviews, essays, and fiction have appeared in a number of publications, including The New Yorker, New York Magazine, Harper’s, The New York Times, and Granta. He has received Colson Whitehead, Image © Madeline Whitehead a MacArthur Fellowship, Guggenheim Fellowship, Whiting Writers Award, Dos Passos Prize, and a fellowship at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers. Whitehead also was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for John Henry Days. He has taught at the University of Houston, Columbia University, Brooklyn College, Hunter College, New York University, Princeton University, and Wesleyan University, and he has been a Writer-in-Residence at Vassar College, the University of Richmond, and the University of Wyoming. Whitehead lives in New York City. Welcome to Middle Tennessee State University! The Center for Historic Preservation (CHP) at Middle Tennessee State University is delighted to host the fifth annual Slave Dwelling Project Conference. The CHP was established in 1984 as MTSU’s first Center of Excellence and one of the nine original centers at the state’s universities administered by the Tennessee Board of Regents at the time. -

Patient Safety for Ellen Patient Safety

Patient Safety For Ellen Patient Safety Perspectives on Evidence, Information and Knowledge Transfer Edited by Lorri ZiPPerer © Lorri Zipperer 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Lorri Zipperer has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work. Published by Gower Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3-1 Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-3818 Surrey, GU9 7PT USA England www.gowerpublishing.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zipperer, Lorri A., 1959- Patient safety : perspectives on evidence, information and knowledge transfer / by Lorri Zipperer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-3857-1 (hbk) -- ISBN 978-1-4094-3858-8 (ebk) -- ISBN 978-1-4724-0243-1 (epub) 1. Hospital patients--Safety measures. 2. Medical errors--Prevention. I. Title. RA965.6.Z57 2014 610.28’9--dc23 2013028766 ISBN 978 1 4094 3857 1 (hbk) ISBN 978 1 4094 3858 8 (ebk – PDF) ISBN 978 1 4724 0243 1 (ebk – ePUB) III Contents List of Figures ix List of Tables xi About the Editor xiii About the Contributors xv Foreword xxix Preface xxxv List of Abbreviations xliii Acknowledgements xlv PART 1 CONTEXT FOR INNOVATION AND IMPROVEMENT Chapter 1 Patient Safety: A Brief but Spirited History 3 Robert L. -

FAN EXPO Dallas Announces First Ever Masters of Cosplay Grand Prix

FAN EXPO Dallas Announces First Ever Masters of Cosplay Grand Prix Dallas event to host the Central Qualifier Saturday, April 7 Winner to go Toronto to compete in Masters of Cosplay Grand Prix Sept. 1 DALLAS (Feb. 20, 2018) – FAN EXPO Dallas – the largest comics, sci-fi, horror, anime and gaming event in Texas – is proud to host the Central Qualifier of a brand-new cosplay competition called the Masters of Cosplay Grand Prix, which will take place Sept. 1, 2018, in Toronto. The Central Qualifier will be held April 7, 2018, during FAN EXPO Dallas. Cosplay is the practice of dressing up in costumes and accessories as a character from a favorite movie, series, book or video game. This competition will be open to any cosplayer age 13 and up who has admission to FAN EXPO Dallas. Costumes must be at least 50 percent handmade or altered. Commissioned costumes will only be allowed if the creator is present. All entrants must pre-register online before the contest. The four divisions, categorized based on skill level, are: Masters Division, Journeyman Division, Novice Division and Youth Division. There will be amazing prizes for the winners of each division, the grand prize being an all-expenses paid trip to FAN EXPO Canada to compete in the Masters of Cosplay Grand Prix where the contestants from each of the qualifying rounds will compete for the ultimate prize of $5,000 and be crowned as FAN EXPO’s very first Master of Cosplay Champion. Cosplay fans can also enter a more casual costume contest and still win great prizes in the Walk-On Costume Contest.