Yeravas of Kodagu, Part XI, Series-9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kannada Versus Sanskrit: Hegemony, Power and Subjugation Dr

================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 17:8 August 2017 UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ================================================================ Kannada versus Sanskrit: Hegemony, Power and Subjugation Dr. Meti Mallikarjun =================================================================== Abstract This paper explores the sociolinguistic struggles and conflicts that have taken place in the context of confrontation between Kannada and Sanskrit. As a result, the dichotomy of the “enlightened” Sanskrit and “unenlightened” Kannada has emerged among Sanskrit-oriented scholars and philologists. This process of creating an asymmetrical relationship between Sanskrit and Kannada can be observed throughout the formation of the Kannada intellectual world. This constructed dichotomy impacted the Kannada world in such a way that without the intellectual resource of Sanskrit, the development of the Kannada intellectual world is considered quite impossible. This affirms that Sanskrit is inevitable for Kannada in every respect of its sociocultural and philosophical formations. This is a very simple contention, and consequently, Kannada has been suffering from “inferiority” both in the cultural and philosophical development contexts. In spite of the contributions of Prakrit and Pali languages towards Indian cultural history, the Indian cultural past is directly connected to and by and large limited to the aspects of Sanskrit culture and philosophy alone. The Sanskrit language per se could not have dominated or subjugated any of the Indian languages. But its power relations with religion and caste systems are mainly responsible for its domination over other Indian languages and cultures. Due to this sociolinguistic hegemonic structure, Sanskrit has become a language of domination, subjugation, ideology and power. This Sanskrit-centric tradition has created its own notion of poetics, grammar, language studies and cultural understandings. -

Dakshin: Vegetarian Cuisine from South India Free

FREE DAKSHIN: VEGETARIAN CUISINE FROM SOUTH INDIA PDF Chandra Padmanabhan | 176 pages | 22 Sep 1999 | Periplus Editions (Hong Kong) Ltd | 9789625935270 | English | Hong Kong, Hong Kong Dakshin : South Indian Bistro Here are some of the most delicious regional south Indian recipes you can try at home. Dosa and chutney are just a brief trailer to a colourful, rich and absolutely fascinating culinary journey that is South India. With its 5 states, 2 union territories, rocky plateau, river valleys and coastal plains, the south of India is extremely different from its Northern counterpart. But before we get into details like ingredients and cooking techniques, let's talk about some aspects that are common to those that live in the South. Firstly, most people eat with their right hand and leave the left one Dakshin: Vegetarian Cuisine from South India for drinking water. Also, licking curry off your finger does taste really good! Rice is their grain of choice and lentils and daals are equally important. Also read: Why people eat with their hands in Kerala? Sambhar is an important dish to South Indians. Photo Credit: iStock Pickles and Pappadams are always served on the side and yogurt makes a frequent appearance as well. Coconut is one of the most important ingredients and is used in various forms: dry, desiccated or as is. Some of the cooking is also done Dakshin: Vegetarian Cuisine from South India coconut oil. The South of India is known as 'the land of spices' and for all the right reasons. Cinnamon, cardamom, cumin, nutmeg, chilli, mustard, curry leaves - the list goes on. -

NOTIFICATION for the POSTS of GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE Applications Are Invited by the Respective R

NOTIFICATION FOR THE POSTS OF GRAMIN DAK SEVAKS CYCLE – II/2019 KERALA CIRCLE RECTT/50-1/DLGS/2019 Applications are invited by the respective recruiting authorities as shown in the annexure ‘I’ against each post, from eligible candidates for the selection and engagement to the following posts of Gramin Dak Sevaks. I. Job Profile:- (i) BRANCH POSTMASTER (BPM) The Job Profile of Branch Post Master will include managing affairs of GDS Branch Post Office, India Posts Payments Bank ( IPPB) and ensuring uninterrupted counter operation during the prescribed working hours using the handheld device/Smartphone supplied by the Department. The overall management of postal facilities, maintenance of records, upkeep of handheld device, ensuring online transactions, and marketing of Postal, India Post Payments Bank services and procurement of business in the villages or Gram Panchayats within the jurisdiction of the Branch Post Office should rest on the shoulders of Branch Postmasters. However, the work performed for IPPB will not be included in calculation of TRCA, since the same is being done on incentive basis.Branch Postmaster will be the team leader of the GDS Post Office and overall responsibility of smooth and timely functioning of Post Office including mail conveyance and mail delivery. He/she might be assisted by Assistant Branch Post Master of the same GDS Post Office. BPM will be required to do combined duties of ABPMs as and when ordered. He will also be required to do marketing, organizing melas, business procurement and any other work assigned by IPO/ASPO/SPOs/SSPOs/SRM/SSRM etc.In some of the Branch Post Offices, the BPM has to do all the work of BPM/ABPM. -

Journeys and Encounters Religion, Society and the Basel Mission In

Documents on the Basel Mission in North Karnataka, Page 5. 1 Missions-Magazin 1846-1849: Translations P. & J.M. Jenkins, October 2007, revised July 2013 Journeys and Encounters Religion, Society and the Basel Mission in Northern Karnataka 1837-1852 Section Five: 1845-1849 General Survey, mission among the "Canarese and in Tulu-Land" 1846 pp. 5.2-4 BM Annual Report [1845-] 1846 pp.5.4-17 Frontispiece & key: Betgeri mission station in its landscape pp.5.16-17 BM Annual Report [1846-] 1847 pp. 5.18-34 Frontispiece & key: Malasamudra mission station in its landscape p.25 Appx. C Gottlob Wirth in the Highlands of Karnataka pp. 5.26-34 BM Annual Report [1847-] 1848 pp. 5.34-44 BM Annual Report [1848-] 1849 pp. 5.45-51 Documents on the Basel Mission in North Karnataka, Page 5. 2 Missions-Magazin 1846-1849: Translations P. & J.M. Jenkins, October 2007, revised July 2013 Mission among the Canarese and in Tulu-Land1 [This was one of the long essays that the Magazin für die neueste Geschichte published in the 1840s about the progress of all the protestant missions working in different parts of India (part of the Magazin's campaign to inform its readers about mission everywhere.2 In 1846 the third quarterly number was devoted to the area that is now Karnataka. The following summarises some of the information relevant to Northern Karnataka and the Basel Mission (sometimes referred to as the German Mission). Quotations are marked with inverted commas.] [The author of the essay is not named, and the report does not usually specify from which missionary society the named missionaries came. -

Updated Proposal to Encode Tulu-Tigalari Script in Unicode

Updated proposal to encode Tulu-Tigalari script in Unicode Vaishnavi Murthy Kodipady Yerkadithaya [ [email protected] ] Vinodh Rajan [ [email protected] ] 04/03/2021 Document History & Background Documents : (This document replaces L2/17-378) L2/11-120R Preliminary proposal for encoding the Tulu script in the SMP of the UCS – Michael Everson L2/16-241 Preliminary proposal to encode Tigalari script – Vaishnavi Murthy K Y L2/16-342 Recommendations to UTC #149 November 2016 on Script Proposals – Deborah Anderson, Ken Whistler, Roozbeh Pournader, Andrew Glass and Laurentiu Iancu L2/17-182 Comments on encoding the Tigalari script – Srinidhi and Sridatta L2/18-175 Replies to Script Ad Hoc Recommendations (L2/16-342) and Comments (L2/17-182) on Tigalari proposal (L2/16-241) – Vaishnavi Murthy K Y L2/17-378 Preliminary proposal to encode Tigalari script – Vaishnavi Murthy K Y, Vinodh Rajan L2/17-411 Letter in support of preliminary proposal to encode Tigalari – Guru Prasad (Has withdrawn support. This letter needs to be disregarded.) L2/17-422 Letter to Vaishnavi Murthy in support of Tigalari encoding proposal – A. V. Nagasampige L2/18-039 Recommendations to UTC #154 January 2018 on Script Proposals – Deborah Anderson, Ken Whistler, Roozbeh Pournader, Lisa Moore, Liang Hai, and Richard Cook PROPOSAL TO ENCODE TIGALARI SCRIPT IN UNICODE 2 A note on recent updates : −−−Tigalari Script is renamed Tulu-Tigalari script. The reason for the same is discussed under section 1.1 (pp. 4-5) of this paper & elaborately in the supplementary paper Tulu Language and Tulu-Tigalari script (pp. 5-13). −−−This proposal attempts to harmonize the use of the Tulu-Tigalari script for Tulu, Sanskrit and Kannada languages for archival use. -

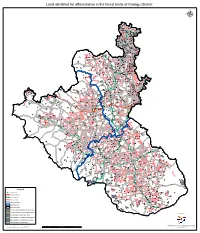

Land Identified for Afforestation in the Forest Limits of Kodagu District Μ

Land identified for afforestation in the forest limits of Kodagu District µ Hampapura Kesuru Santapura Doddakodi Malaganahalli Kasuru Mavinahalli Hosahalli Janardanahalli Nirgunda KallahalliKodlipet Mollepura Kattepura Nandipura Ramenahalli Ichalapura Ramenahalli Chikkakunda Agali Konginahalli Kattepura Mallahalli Doddakunda Basavanahalli Kudlu Besuru Nilavagilu Urugutti Lakham Kudluru Chikkabandara Bettiganahalli Korgallu Bemballur Hemmane Kiribilaha Talaguru Taluru Doddabilaha Avaredalu Lakkenahalle Siraha Hulukadu Kitturu Harohalli Toyahalli Managali Madare Bageri Dandhalli Hosahalli Bettadahalli Dundalli Mudaravalli Kujageri Kerehalli Hosapura Yedehalli Bellarhalli Kallahalli Sanivarsante Chikanahalli Huluse Gudugalale Sirangala Doddakolaturu Choudenahalli Hemmane Sidagalale Settiganahalli Doddahalli Appasethalli Gangavara Vaderapura Kyatanahalli Gopalpura Kysarahalli Bettadahalli Hittalkeri Nidta Menasa Modagadu Sigemarur Hunsekayihosahalli Mulur Ramenahalli Forest Quarters Mailatapura Mallalli Honnekopal Kurudavalli Nagur Amballi Hattihalli Badabanahalli Nandigunda Kodhalli Nagarahalli Kuti Kundahalli Heggula Bachalli Kanave Basavanahalli Harohalli Bidahalli Kumarhalli Santveri Heggademane Singanhalli Koralalhalli Basavanakoppa Hosagutti Kundahalli Inkalli Dinnehesahalli Tolur Shetthalli Hasahalli Jakhanalli Mangalur Nadenahalli Gaudahalli Malambi Sunti Ajjalli Bettadahalli Doddatolur Kugur Chikkara Santhalli Kogekodi Kantebasavanahalli Gejjihanakodu Chennapuri Alur Honnahalli Siddapura Kudigana Hirikara HitiagaddeKallahalli Sulimolate -

Kodagu District, Karnataka

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET KODAGU DISTRICT, KARNATAKA SOMVARPET KODAGU VIRAJPET SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE AUGUST 2007 FOREWORD Ground water contributes to about eighty percent of the drinking water requirements in the rural areas, fifty percent of the urban water requirements and more than fifty percent of the irrigation requirements of the nation. Central Ground Water Board has decided to bring out district level ground water information booklets highlighting the ground water scenario, its resource potential, quality aspects, recharge – discharge relationship, etc., for all the districts of the country. As part of this, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore, is preparing such booklets for all the 27 districts of Karnataka state, of which six of the districts fall under farmers’ distress category. The Kodagu district Ground Water Information Booklet has been prepared based on the information available and data collected from various state and central government organisations by several hydro-scientists of Central Ground Water Board with utmost care and dedication. This booklet has been prepared by Shri M.A.Farooqi, Assistant Hydrogeologist, under the guidance of Dr. K.Md. Najeeb, Superintending Hydrogeologist, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore. I take this opportunity to congratulate them for the diligent and careful compilation and observation in the form of this booklet, which will certainly serve as a guiding document for further work and help the planners, administrators, hydrogeologists and engineers to plan the water resources management in a better way in the district. Sd/- (T.M.HUNSE) Regional Director KODAGU DISTRICT AT A GLANCE Sl.No. -

Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-03-06 Document version: 2.6 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1. General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Kannada LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document: proposal-kannada-lgr-06mar19-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document: kannada-test-labels-06mar19-en.txt 2. Script for which the LGR is Proposed ISO 15924 Code: Knda ISO 15924 N°: 345 ISO 15924 English Name: Kannada Latin transliteration of the native script name: Native name of the script: ಕನ#ಡ Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-4 Some languages using the script and their ISO 639-3 codes: Kannada (kan), Tulu (tcy), Beary, Konkani (kok), Havyaka, Kodava (kfa) 1 Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) 3. Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It 3.1 Kannada language Kannada is one of the scheduled languages of India. It is spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka State of India. It is one of the major languages among the Dravidian languages. Kannada is also spoken by significant linguistic minorities in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, Goa and abroad. -

Thinking the Future: Coffee, Forests and People

Thinking the Future: Coffee, Forests and People Conservation and development in Kodagu Advanced Master « Forêt Nature Société » - 2011 Maya Leroy, Claude Garcia, Pierre-Marie Aubert, Vendé Jérémy Claire Bernard, Joëlle Brams, Charlène Caron, Claire Junker, Guillaume Payet, Clément Rigal, Samuel Thevenet AgroParisTech -ENGREF Environmental evaluation training course TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................5 I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 15 II. METHODS ................................................................................................................ 19 II.1. TERRITORIAL PROSPECTIVE: GOALS AND OBJECTIVES .......................................................19 II.2. UNDERSTANDING THE TERRITORY: A STRATEGIC DIAGNOSIS ............................................21 II.3. INTERVIEWING TO UNDERSTAND PRESENT STRATEGIES AND IMAGINE FUTURE CHANGES 21 II.4. IMPLEMENTING OUR METHODOLOGY: A FOUR STEP APPROACH.........................................24 III. LANDSCAPE MODEL ......................................................................................... 27 III.1. HEURISTIC MODEL: REPRESENTING THE LANDSCAPE ...................................................28 III.2. COUNTERBALANCING EVOLUTION FACTORS: CONFLICTS AND LAND TENURE SYSTEM -

Franchisees in the State of Karnataka (Other Than Bangalore)

Franchisees in the State of Karnataka (other than Bangalore) Sl. Place Location Franchisee Name Address Tel. No. No. Renuka Travel Agency, Opp 1 Arsikere KEB Office K Sriram Prasad 9844174172 KEB, NH 206, Arsikere Shabari Tours & Travels, Shop Attavara 2 K.M.C M S Shabareesh No. 05, Zephyr Heights, Attavar, 9964379628 (Mangaluru) Mangaluru-01 No 17, Ramesh Complex, Near Near Municipal 3 Bagepalli S B Sathish Municipal Office, Ward No 23, 9902655022 Office Bagepalli-561207 New Nataraj Studio, Near Private Near Private Bus 9448657259, 4 Balehonnur B S Nataraj Bus Stand, Iliyas Comlex, Stand 9448940215 Balehonnur S/O U.N.Ganiga, Barkur 5 Barkur Srikanth Ganiga Somanatheshwara Bakery, Main 9845185789 (Coondapur) Road, Barkur LIC policy holders service center, Satyanarayana complex 6 Bantwal Vamanapadavu Ramesh B 9448151073 Main Road,Vamanapadavu, Bantwal Taluk Cell fix Gayathri Complex, 7 Bellare (Sulya) Kelaginapete Haneef K M 9844840707 Kelaginapete, Bellare, Sulya Tq. Udayavani News Agent, 8 Belthangady Belthangady P.S. Ashok Shop.No. 2, Belthangady Bus 08256-232030 Stand, Belthangady S/O G.G. Bhat, Prabhath 9 Belthangady Belthangady Arun Kumar 9844666663 Compound, Belthangady 08282 262277, Stall No.9, KSRTC Bus Stand, 10 Bhadravathi KSRTC Bus Stand B. Sharadamma 9900165668, Bhadravathi 9449163653 Sai Charan Enterprises, Paper 08282-262936, 11 Bhadravathi Paper Town B S Shivakumar Town, Bhadravathi 9880262682 0820-2562805, Patil Tours & Travels, Sridevi 2562505, 12 Bramhavara Bhramavara Mohandas Patil Sabha bhavan Building, N.H. 17, 9845132769, Bramhavara, Udupi Dist 9845406621 Ideal Enterprises, Shop No 4, Sheik Mohammed 57A, Afsari Compound, NH 66, 8762264779, 13 Bramhavara Dhramavara Sheraj Opposite Dharmavara 9945924779 Auditorium Brahmavara-576213 M/S G.R Tours & Travels, 14 Byndur Byndoor Prashanth Pawskar Building, N.H-17, 9448334726 Byndoor Sl. -

Mgl-Int-1-2013-Unpaid Shareholders List As on 31

DEMAT ID_FOLIO NAME WARRANT NO MICR DIVIDEND AMOUNT ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY PINCODE JH1 JH2 000404 MOHAMMED SHAFEEQ 27 508 30000.00 PUTHIYAVEETIL HOUSE CHENTHRAPPINNI TRICHUR DIST. KERALA DR. ABDUL HAMEED P.A. 002679 NARAYANAN P S 51 532 12000.00 PANAT HOUSE P O KARAYAVATTOM, VALAPAD THRISSUR KERALA 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 89 570 36000.00 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 IN30066910088862 K PHANISRI 116 597 15900.00 Q NO 197A SECTOR I UKKUNAGARAM VISAKHAPATNAM 530032 IN30047640586716 P C MURALEEDHARAN NAIR 120 601 15000.00 DOOR NO 92 U P STAIRS DEVIKALAYA 8TH MAIN RD 9TH CROSS SARASWATHIPURAM MYSORE 570009 001424 BALARAMAN S N 126 607 60000.00 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 002473 GUNASEKARAN V 128 609 30000.00 NO.5/1324,18TH MAIN ROAD ANNA NAGAR WEST CHENNAI 600040 000697 AMALA S. 143 624 12000.00 36 CAR STREET SOWRIPALAYAM COIMBATORE TAMILNADU 641028 000953 SELVAN P. 150 631 18000.00 18, DHANALAKSHMI NAGAR AVARAMPALAYAM ROAD, COIMBATORE TAMILNADU 641044 001209 PANCHIKKAL NARAYANAN 153 634 60000.00 NANU BHAVAN KACHERIPARA KANNUR KERALA 670009 002985 BABY MATHEW 173 654 12000.00 PUTHRUSSERY HOUSE PULIKKAYAM KODANCHERY CALICUT 673580 001680 RAVI P 182 663 30000.00 SUDARSAN CHEMBAKKASSERY TATTAMANGALAM KERALA 678102 001440 RAJI GOPALAN 198 679 60000.00 ANASWARA KUTTIPURAM THIROOR ROAD KUTTYPURAM KERALA 679571 001756 UNNIKRISHNAN P 222 703 30000.00 'SREE SAILAM' PUDUKULAM ROAD PUTHURKKARA, AYYANTHOLE POST THRISSUR 680003 AMBIKA C P 1201090001296071 REBIN SUNNY 227 708 18750.00 21/14 BEETHEL P O AYYANTHOLE THRISSUR 680003 IN30163741039292 NEENAMMA VINCENT 260 741 18000.00 PLOT NO103 NEHRUNAGAR KURIACHIRA THRISSUR 680006 002191 PRESANNA BABU M V 310 791 30000.00 MURIYANKATTIL HOUSE EDAKULAM IRINJALAKUDA, THRISSUR KERALA 680121 SHAILA BABU 001567 ABUBAKER P B 375 856 15000.00 PUITHIYAVEETIL HOUSE P O KURUMPILAVU THRISSUR KERALA 680564 IN30163741303442 REKHA M P 419 900 20250.00 FLAT NO 571 LUCKY HOME PLAZA NEAR TRIPRAYAR TEMPLE NATTIKA P O THRISSUR 680566 1201090004031286 KUMARAN K K . -

Karnataka, India

Natural Perception by Kodagu communities Georgina Zamora - Karnataka, India- UNIVERSITAT AUTÒNOMA DE BARCELONA Tutor Victoria Reyes-García, ICREA Ethnoecology Laboratory Georgina Zamora Quílez Degree on Environmental Sciences 1 Natural Perception by Kodagu communities Georgina Zamora Detailed Index Advertisement ............................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................... 6 I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 7 II. LITERATURE REVISION .......................................................................................... 8 1. Natural Capital Origins ............................................................................................. 8 2. Natural Goods and services....................................................................................... 9 2.1 Natural resources............................................................................................... 9 2.2 Ecosystem services ............................................................................................ 9 2.3 NNRR/Ecosystem services and sustainable development ..................................... 10 3 Natural Capital........................................................................................................ 11 3.1 Concept..........................................................................................................