Physical Therapy Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1992-1995 (Pdf)

SURNAME GIVENS EV PLACE AGE/BORN SPOUSE PAPER DATE PG NOTES/INFO ABBOTT Michelle Lynn B Richmond, BC FP 24-Feb-1993 B11 Dtr/o Doug and Peggy Abbott, 9 lb 14 oz ABEL Michael David (Cpl.) D Belet Huen, age 27 FP 7-May-1993 1 Son of Diana & David Abel of Sidney, BC, see obit 12 May 1993 page Somalia B10 ABRAHAMS Clifford Sidney D Comox born 1907 Blanche Abrahams FP 28-May-1993 B11 Born Luton, Beds., England, wife died 1985, father of Judy and Jim, Coleman history given ABRAHAMS Clifford Sidney D Comox age 86 FP 2-Jun-1993 B10 Family named, lengthy biography Coleman ABRIC (boy) B Comox FP 19-Jan-1994 B7 Son of Steve and Nancy Abric, bro/o Stephanie, other family named. 9 lb 5 oz ABRIC Stephanie Patricia B Comox FP 1-Apr-1992 B9 Dtr/o Steve and Nancy Abric, gdtr/o George/Buntie, Harvey/Kathie Carnaham ADAMS Conrad D not given FP 19-Aug-1992 B9 In Memoriam ADAMSCHEK Elizabeth "Wally" D Comox born 1900 Otto RICHTER FP 19-Nov-1993 C1 Nee ADAMSCHEK, born Recklinghausen Germany dtr/o Marie & Rudolf, large family named bur. Courtenay Civic Cemetery AGAR Mary Emma D Comox age 89 Wilfred Agar FP 27-May-1992 B9 Widowed in 1969, 5 sons, 6 dtrs not named, service at Piercy FH AITKEN Alexandra Elizabeth B not given FP 29-Apr-1994 B9 Sis to Maranda and Marleah, dtr/o ? 9 lb AITKEN Evelyn D not given born 1918 FP 18-May-1994 B9 Nee AITKEN, Born at Bevan, BC, family named ALAHAIVALA Katlyn Maraija B not given FP 31-Jul-1992 B6 Dtr/o Raimo and Laurie Alahaivala, 6 lb 11 oz ALBRECHT James M Comox Edith OWNER FP 3-Aug-1994 18 50th wedding anniversary ALBRIGHT Martin Stephen D Victoria age 82 Evelyn Albright FP 10-Jun-1992 B9 Widowed in 1986, father of Reid and Nedra, service at St. -

Germanic Surname Lexikon

Germanic Surname Lexikon Most Popular German Last Names with English Meanings German for Beginners: Contents - Free online German course Introduction German Vocabulary: English-German Glossaries For each Germanic surname in this databank we have provided the English Free Online Translation To or From German meaning, which may or may not be a surname in English. This is not a list of German for Beginners: equivalent names, but rather a sampling of English translations of German names. Das Abc German for Beginners: In many cases, there may be several possible origins or translations for a Lektion 1 surname. The translation shown for a surname may not be the only possibility. Some names are derived from Old German and may have a different meaning from What's Hot that in modern German. Name research is not always an exact science. German Word of the Day - 25. August German Glossary of Abbreviations: OHG (Old High German) Words to Avoid - T German Words to Avoid - Glossary Warning German Glossary of Germanic Last Names (A-K) Words to Avoid - With English Meanings Feindbilder German Words to Avoid - Nachname Last Name English Meaning A Special Glossary Close Ad A Dictionary of German Aachen/Aix-la-Chapelle Names Aachen/Achen (German city) Hans Bahlow, Edda ... Best Price $16.95 Abend/Abendroth evening/dusk or Buy New $19.90 Abt abbott Privacy Information Ackerman(n) farmer Adler eagle Amsel blackbird B Finding Your German Ancestors Bach brook Kevan M Hansen Best Price $4.40 Bachmeier farmer by the brook or Buy New $9.13 Bader/Baader bath, spa keeper Privacy Information Baecker/Becker baker Baer/Bar bear Barth beard Bauer farmer, peasant In Search of Your German Roots. -

Ethnicity and Geriatric Assessment

Gallo_FM_i-xviii 8/1/05 5:23 PM Page i HANDBOOK OF GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT Fourth Edition Edited by Joseph J. Gallo, MD, MPH Associate Professor Department of Family Practice and Community Medicine Department of Psychiatry University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Hillary R. Bogner, MD, MSCE Assistant Professor Department of Family Practice and Community Medicine University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Terry Fulmer, PhD, RN, FAAN The Erline Perkins McGriff Professor & Head, Division of Nursing New York University New York, New York Gregory J. Paveza, MSW, PhD Interim Associate Vice President for Academic Affairs University of South Florida – Lakeland Lakeland, Florida Gallo_FM_i-xviii 8/1/05 5:23 PM Page ii World Headquarters Jones and Bartlett Publishers 40 Tall Pine Drive Sudbury, MA 01776 978-443-5000 [email protected] www.jbpub.com Jones and Bartlett Publishers Canada 6339 Ormindale Way Mississauga, ON L5V 1J2 CANADA Jones and Bartlett Publishers International Barb House, Barb Mews London W6 7PA UK Jones and Bartlett’s books and products are available through most bookstores and online booksellers. To contact Jones and Bartlett Publishers directly, call 800-832-0034, fax 978-443-8000, or visit our website at www.jbpub.com. Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Jones and Bartlett’s publications are available to corporations, professional associations, and other qualified organizations. For details and specific discount information, contact the special sales department at Jones and Bartlett via the above contact information or send an email to [email protected]. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. -

1977 Commencement Program State University of New York College at Cortland

SUNY College Cortland Digital Commons @ Cortland College Commencements Programs College Commencements 5-21-1977 1977 Commencement Program State University of New York College at Cortland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/ commencements_programs Recommended Citation State University of New York College at Cortland, "1977 Commencement Program" (1977). College Commencements Programs. 135. https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/commencements_programs/135 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the College Commencements at Digital Commons @ Cortland. It has been accepted for inclusion in College Commencements Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Cortland. For more information, please contact [email protected]. State University of New York COLLEGE AT CORTLAND Commencement, May 21, 1977 Alma Mater By lofty elm trees shaded round, Tioughnloga near, Our grand old Cortland College stands, To all of us how dear I We'll sing to thee, dear Alma Mater Of love that shall never die, We'll strive for thy glory eternal, Keep thy stainless honor high. Inspiring each son and each daughter The noblest aims to try, AII/hy fame and thy spirit, Thy might are ours As the swift years hurry by. The College's 109th Year Faculty Marshals Program David G. Miller Mace Bearer PROCESSIONAL Pomp and Circumstance .....................................•............ Edward Elgar Patricia Allen Morris R. Bogard NATIONAL ANTHEM Joseph W. Brownell Van A. Burd Carl H. Evans INVOCATION The Rev. R. Daniel Delorme G. Raymond Fisk Pastor, St. Margaret's Church, Homer Samuel L. Forcucci John A. Gustafson Karel Horak WELCOME Richard C. Jones Ellis A. Johnson Boris Leaf PreSident laRetha Leyman Carl B. -

Ancient DNA Studies of Human Evolution

Ancient DNA studies of human evolution Christina Jane Adler Australian Centre for Ancient DNA School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of Adelaide A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Adelaide January 2012 CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER ONE Introduction…………………………………………………………. 1 1.1 The aims of the thesis………………………………………………………….. 3 1.2 Neolithic Revolution…………………………………………………………... 5 1.2.1 Origins and reasons for the development of agriculture……………………………………………………………. 5 1.2.2 The introduction of the Neolithic Package to Europe and the influence of the transition to agriculture on the population structure of modern Europeans……………………………………………………………... 9 1.2.2.1 Support for the cultural diffusion hypothesis – Pleistocene settlement events …………………………………………... 13 1.2.2.2 Support for the demic diffusion hypothesis – Neolithic settlement events…………………………………………… 17 1.2.3 Dietary changes associated with the introduction of agriculture……... 24 1.2.4 Health changes associated with the introduction of agriculture………. 27 1.3 Application of ancient DNA to study human evolutionary questions…………. 30 1.3.1 Technical challenges of using ancient DNA………………………….. 31 1.3.2 Using ancient human DNA to study past demographic events……….. 34 1.3.3 Using ancient bacterial DNA to study the evolution of pathogens…… 36 1.3.3.1 Dental calculus……………………………………………... 39 1.4 Thesis structure………...………………………………………………………. 46 References……………………………………………………………………………….. 58 CHAPTER TWO Adler, C J, Haak, W, Donlon, D & Cooper, A 2011. Survival and recovery of DNA from ancient teeth and bones. Journal of Archaeological Science, 38, 956-964..………………………………………………………………………………… 62 Supplementary material………………………………………………………... 72 CHAPTER THREE Ancient DNA reveals that population dynamics during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age substantially influenced the population structure of modern Central Europeans………………………………………………………………. -

Burial List by Section

Cemetery - Burial List 1ST ADDITION Last Name First Name Middle Maiden Name Section Block Lot Grave Died Age Burial Date ADAMS NELLIE OR MILLIE 1ST ADDITION 182 5 9/13/1913 0 ADAMSON JENNIE (JANICE) 1ST ADDITION 256 2 11/8/1909 56 ADCOCK SARAH E. 1ST ADDITION 254 4 7/15/1958 0 ADCOCK DAVID F. 1ST ADDITION 254 5 11/24/1918 44 AINSWORTH EMMA 1ST ADDITION 17 2 4/30/1955 81 AINSWORTH CHARLES 1ST ADDITION 212 3 9/19/1907 0 ALEXANDER T. C. 1ST ADDITION 224 5 7/8/1907 0 ALEXANDER LAURA 1ST ADDITION 84 4 12/22/1956 81 ALLDREDGE JOHN P. 1ST ADDITION 43 5 5/11/1924 54 ALLDREDGE CHARLES NORMAN 1ST ADDITION 43 3 3/26/1938 28 ALLGIERS CLIFTON ORVILLE 1ST ADDITION 125 3 0 ALLGIERS ORVILLE CLIFTON 1ST ADDITION 125 3 5/7/1915 0 AMRINE MAHLON 1ST ADDITION 42 3 10/29/1927 78 AMRINE ALVA P. 1ST ADDITION 42 1 10/2/1918 27 AMRINE CHARLOTTE 1ST ADDITION 42 2 1/14/1927 72 AMRINE CORALIE 1ST ADDITION 42 4 3/16/1985 95 ANDERSON BABY OF ALVA 1ST ADDITION 270 2 3/25/1912 0 ANDERSON SARAH M. 1ST ADDITION 201 2 4/16/1924 64 ANDERSON GERTRUDE A. 1ST ADDITION 201 3 11/22/1982 75 Thursday, September 5, 2019 1ST ADDITION Last Name First Name Middle Maiden Name Section Block Lot Grave Died Age Burial Date ANDERSON WILLIAM 1ST ADDITION 201 1 7/1/1908 0 ANDERSON BILLY 1ST ADDITION 201 5 6/10/1926 1 ANDERSON WILLIAM C. -

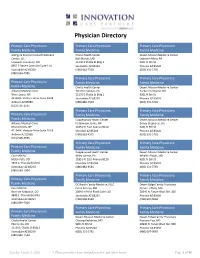

Physician Directory

Physician Directory Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Family Medicine Family Medicine Family Medicine Allergy & Environmental Treatment Cholla Health Center Desert Mission Medicine Center Center, LLC Bell Marvin, MD Ottmann Alicia, PA Liszewski Lawrence, DO 11130 E Cholla St Bldg 1 9201 N 5th St 8952 E Desert Cove Ave Suite 114 Scottsdale AZ 85259 Phoenix AZ 85020 Scottsdale AZ 85260 (480) 882-7520 (602) 331-5792 (480) 634-2985 Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Family Medicine Family Medicine Family Medicine Cholla Health Center Desert Mission Medicine Center Alliance Medical Clinic Tinocco Camilyn, PA Tucker Constance, DO Wren Diane, NP 11130 E Cholla St Bldg 1 9201 N 5th St 42104 N. Venture Drive Suite D118 Scottsdale AZ 85259 Phoenix AZ 85020 Anthem AZ 85086 (480) 882-7520 (602) 331-5792 (623) 505-6565 Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Family Medicine Family Medicine Family Medicine Copperwood Health Center Desert Mission Medicine Center Alliance Medical Clinic Hutchinson Jamie, NP Briney Stephanie, DO Moore Molly, NP 11851 N. 51st Avenue B110 9201 N 5th St 42104 N. Venture Drive Suite D118 Glendale AZ 85304 Phoenix AZ 85020 Anthem AZ 85086 (480) 882-4545 (602) 331-5792 (623) 505-6565 Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Family Medicine Family Medicine Family Medicine Copperwood Health Center Desert Mission Medicine Center Care MD PLC Wiley Larissa, PA Whallon Ralph, MD Matin Vafa, DO 11851 N. 51st Avenue B110 9201 N 5th St 4845 E. Thunderbird Rd. Glendale AZ 85304 Phoenix AZ 85020 Scottsdale AZ 85254 (480) 882-4545 (602) 331-5792 (480) 699-7004 Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Primary Care Physicians: Family Medicine Family Medicine Family Medicine DC Ranch Family Medicine, PLLC Desert Ridge Family Physicians Care MD PLC Perez Arneyo, MD Nelson Tiffany, MD Baniriah Katayoun, DO 20945 N Pima Road Suite 110 20940 N. -

PHYSICAL THERAPY PRACTICE the Publication of the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, APTA

2019 / volume 31 / number 2 ORTHOPAEDIC PHYSICAL THERAPY PRACTICE The publication of the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, APTA FEATURE: Effectiveness of a Standing Workstation on Perceived Pain & Function: A Case Series 7239_OP_Apr.indd 501 3/27/19 1:01 PM 7239_OP_Apr.indd 502 3/27/19 1:01 PM Need Help to Prepare for the OCS? Check out AOPT’s Current Concepts & Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) CURRENT CONCEPTS OF ORTHOPAEDIC PHYSICAL THERAPY, 4TH ED. ISC 26.2 Topics and Authors • Clinical Reasoning and Evidence-based Practice— Nicole Christensen, PT, PhD, MAppSc; Benjamin Boyd, PT, DPTSc, OCS; Jason Tonley, PT, DPT, OCS • The Shoulder: Physical Therapy Patient Management Using Current Evidence—Todd S. Ellenbecker, DPT, MS, SCS, OCS, CSCS; Robert C. Manske, DPT, MEd, SCS, ATC, CSCS; Marty Kelley, PT, DPT, OCS • The Elbow: Physical Therapy Patient Management Using Current Evidence—Chris A. Sebelski, PT, DPT, PhD, OCS, CSCS • The Wrist and Hand: Physical Therapy Patient Management Using Current Evidence— Mia Erickson, PT, EdD, CHT, ATC; Carol Waggy, PT, PhD, CHT; Elaine F. Barch, PT, DPT, CHT • The Temporomandibular Joint: Physical Therapy Patient Management Using Current Evidence—Sally Ho, PT, DPT, MS, OCS CURRENT CONCEPTS OF • The Cervical Spine: Physical Therapy Patient Management ORTHOPAEDIC PHYSICAL THERAPY (4th Edition) Using Current Evidence—Michael B. Miller, PT, DPT, OCS, PHYSICAL THERAPY (4th Edition) ISC 26.2, CURRENT CONCEPTS OF ORTHOPAEDIC Independent Study Course 26.2 FAAOMPT, CCI • The Thoracic Spine: Physical Therapy Patient Management Using Current Evidence— Scott Burns, PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT; William Egan, PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT • The Lumbar Spine: Physical Therapy Patient Management Using Current Evidence—Paul F. -

Spring Commencement University of Northern Iowa Cedar Falls, Iowa May 10-11, 2019

Spring Commencement University of Northern Iowa Cedar Falls, Iowa May 10-11, 2019 Dear Panther Family, The purpose of higher education is to positively impact society through the lives of our alumni, students, faculty, and staff. UNI makes a positive difference in the world by providing a high quality learning environment that empowers our students to discover where they belong. We also fulfill our purpose by advancing knowledge, promoting creativity, and solving problems in partnership with the people, schools, communities, and industries we serve. Commencement offers an opportunity to pause and celebrate the accomplishments of our students and the important work we do to prepare graduates for lives of purpose through their careers and in their homes and communities. To the graduates of the Class of 2019—Congratulations! You make us all Panther Proud. We hope you stay engaged with your Alma Mater. To the faculty and staff who prepared our graduates for success throughout their lives, thank you for your dedication to helping our students meet their educational, professional, and personal life goals. Panther Proud! Mark A. Nook President Table of Contents Board of Regents . 2 Institutional Leadership . .2 University Honors Program . 4 Legacy Graduates . .4 Military Science . 4 Merchant Scholarship. 5 Outstanding Student Leader . 5 Purple and Old Gold Awards . 6 Lux Service Award. 8 7 p.m. Program . .10 College of Business Administration. .12 College of Social and Behavioral Sciences �����������������������������������������������������������������23 10 a.m. Program . .34 Division of Continuing Education and Special Programs ��������������������������������������������36 College of Education . .38 2 p.m. Program . .52 College of Humanities, Arts and Sciences . -

University+Catalog++2020-21.Pdf

E Welcome to the A.T. Still University family! It is an exciting time to be part of this dynamic, growing University, and I am pleased you have chosen to pursue your dreams with us. There is no place like ATSU. Students, faculty, staff, Board of Trustees, and communities work together to achieve outcomes only possible through extraordinary teamwork and alliances. At ATSU you will experience the benefits of rural and urban perspectives on healthcare, a commitment to whole person and whole community health, a family approach to nurturing student learning and personal growth, interprofessional experiences, and an inclusive and collaborative environment. May your time at ATSU be filled with professional success and a great sense of accomplishment as you learn to become tomorrow's healers and healthcare leaders. Yours in service, Craig M. Phelps, DO, '84 President P.S. Do you have an idea to make ATSU a better place to learn? Email your idea to ATSU Idea Box at [email protected], and I will personally respond. ATSU 2020-21 UNIVERSITY CATALOG A.T. Still University of Health Sciences | 2020-21 University Catalog 2 Catalog Effective Date ................................................................................................................................................. 16 Academic Calendar ...................................................................................................................................................... 16 Contact Us .................................................................................................................................................................. -

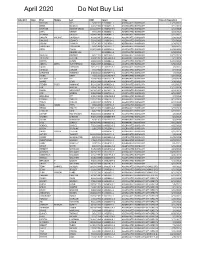

April 2020 Do Not Buy List

April 2020 Do Not Buy List State ID # State First Middle Last DOB Case # Crime Date of Disposition MICHAEL BIES 5/9/1972 B 1506041--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 11/19/2015 BRIAN BLEDSOE 4/26/1982 B 1506256--3 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 3/11/2016 STEPHAN BOOKER-CROSS 11/11/1997 B 1704706-B-1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 4/13/2018 JOHN CROSBY 7/7/1959 B 1603661--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 3/23/2017 LEVENSKI CROSSTY 12/24/1989 B 1604044--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 2/21/2017 DAKOTA MICHAEL DAVIDSON 4/10/1995 B 1804600--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 2/20/2019 DWUANE DELANEY 3/14/1983 B 1400409--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 7/24/2014 JOSEPH DEWALD 1/29/1982 B 1501858--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 9/16/2015 LANGSTAFF DICKERSON 6/6/1981 B 1502365--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 10/9/2015 GREG EVANS 11/27/1985 B 1605054--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 12/20/2016 GENESIS HILL B 9103654--3 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 9/30/2019 NAKEITH GINYARD 6/2/1997 B 1602168--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 10/19/2016 TYEWONE GOODIN 3/30/1997 B 1805684-A-3 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 8/1/2019 DARRYL GUMM 4/20/1966 B 1506042--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 12/23/2015 ADRIAN DEON HUTCHERSON 9/26/1997 B 1803682--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 9/30/2019 DAVID JOHNSON 3/31/1977 B 1702193-B-1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 7/3/2017 DANIELLE JORDAN 7/5/1984 B 1403213--1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 8/7/2014 CHRISTINE KENDRICK 2/22/2000 B 1807247-A-1 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 4/3/2019 JAMES KIRBY 7/2/1992 B 1501469-B-4 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 3/24/2016 WILLIAM D LEE 3/20/1968 B 1302162--4 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 5/14/2014 MARIO LEWIS 8/23/1988 B 1501469-A-4 AGGRAVATED BURGLARY 3/30/2016 STEVEN TYLER MANNING 8/14/1986 -

16-17+QA1+Final.Pdf

16-17 ATSU University Catalog – Quarterly Addendum ............................................................................................... 2 Effective Date ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Corrections .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 About ATSU .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 ATSU Board of Trustees ............................................................................................................................................ 2 State Licensure ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 ATSU Faculty Listing ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Arizona School of Health Sciences (ASHS) .................................................................................................................... 3 Academic Warning ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Orthopedic Physical Therapy Residency ....................................................................................................................