Via Issuelab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

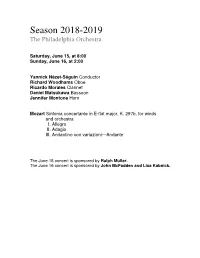

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

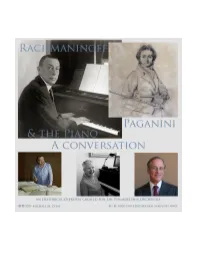

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation Tracks and clips 1. Rachmaninoff in Paris 16:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, Michael Rabin, EMI 724356799820, recorded 9/5/1958. b. Sergey Rachmaninoff (SR), Rapsodie sur un theme de Paganini, Op. 43, SR, Leopold Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (PO), BMG Classics 09026-61658, recorded 12/24/1934 (PR). c. Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (FC), Twelve Études, Op. 25, Alfred Cortot, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) 456751, recorded 7/1935. d. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, SR, Eugene Ormandy (EO), PO, Naxos 8.110601, recorded 12/4/1939.* e. Carl Maria von Weber, Rondo Brillante in E♭, J. 252, Julian Jabobson, Meridian CDE 84251, released 1993.† f. FC, Twelve Études, Op. 25, Ruth Slenczynska (RS), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3798, released 1978. g. SR, Preludes, Op. 32, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. h. Georges Enesco, Cello & Piano Sonata, Op. 26 No. 2, Alexandre Dmitriev, Alexandre Paley, Saphir Productions LVC1170, released 10/29/2012.† i. Claude Deubssy, Children’s Corner Suite, L. 113, Walter Gieseking, Dante 167, recorded 1937. j. Ibid., but SR, Victor B-24193, recorded 4/2/1921, TvJ35-zZa-I. ‡ k. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, Walter Gieseking, John Barbirolli, Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Music & Arts MACD 1095, recorded 2/1939.† l. SR, Preludes, Op. 23, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. 2. Rachmaninoff & Paganini 6:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, op. cit. b. PR. c. Arcangelo Corelli, Violin Sonata in d, Op. 5 No. 12, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Linn CKD 412, recorded 1/11/2012.♢ d. -

Program Notes | Yannick and Manny

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, November 29, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, November 30, at 8:00 Saturday, December 1, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Emanuel Ax Piano Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 83 I. Allegro non troppo II. Allegro appassionato III. Andante—Più adagio—Tempo I IV. Allegretto grazioso—Un poco più presto Intermission Brown Perspectives United States premiere Dvořák Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 I. Allegro maestoso II. Poco adagio III. Scherzo: Vivace IV. Finale: Allegro This program runs approximately 2 hours, 5 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Elia D. Buck and Caroline B. Rogers. The November 29 concert is also sponsored by the Louis N. Cassett Foundation. The November 30 concert is sponsored by Alexandra Edsall and Robert Victor. The December 1 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us following the November 30 and December 1 concerts for a free Organ Postlude featuring Peter Richard Conte. Brahms Prelude, from Prelude and Fugue in G minor Brahms Fugue in A-flat minor Dvořák/transcr. Conte Humoresque, Op. 101, No. 7 Widor Toccata, from Organ Symphony No. 5 in F minor, Op. 42, No. 1 The Organ Postludes are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

Season 2019-2020

23 Season 2019-2020 Thursday, September 19, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, September 20, at 2:00 Saturday, September 21, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Sunday, September 22, Hélène Grimaud Piano at 2:00 Coleman Umoja, Anthem for Unity, for orchestra World premiere—Philadelphia Orchestra commission Bartók Piano Concerto No. 3 I. Allegretto II. Adagio religioso—Poco più mosso—Tempo I— III. Allegro vivace—Presto—Tempo I Intermission Dvořák Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 (“From the New World”) I. Adagio—Allegro molto II. Largo III. Scherzo: Molto vivace IV. Allegro con fuoco—Meno mosso e maestoso— Un poco meno mosso—Allegro con fuoco This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. LiveNote® 2.0, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. These concerts are sponsored by Leslie A. Miller and Richard B. Worley. These concerts are part of The Philadelphia Orchestra’s WomenNOW celebration. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 ® Getting Started with LiveNote 2.0 » Please silence your phone ringer. » Make sure you are connected to the internet via a Wi-Fi or cellular connection. » Download the Philadelphia Orchestra app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. » Once downloaded open the Philadelphia Orchestra app. » Tap “OPEN” on the Philadelphia Orchestra concert you are attending. » Tap the “LIVE” red circle. -

2019 Tour of China News Release | the Philadelphia Orchestra

N E W S R E L E A S E FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 29, 2019 Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin to Lead The Philadelphia Orchestra on 2019 Tour of China Marking 40 Years of U.S.-China Diplomatic Relations May 16-28, 2019 Tour highlights include official 40th anniversary concerts in Beijing and Shanghai, weeklong residency in Beijing, Orchestra debut in Nanjing, and a performance at the first-ever China International Music Competition Concerts and residency activities will foster people-to-people exchange (Philadelphia, January 29, 2019)—In a time of uncertainty in United States and China relations, The Philadelphia Orchestra will serve as a cultural bridge, fostering meaningful people-to-people exchange through music during its 2019 Tour of China, May 16-28, 2019. Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin will lead the tour, bringing the “Philadelphia Sound” to Beijing, Tianjin, Hangzhou, Nanjing, and Shanghai, with Shanghai-born pianist Haochen Zhang as soloist. The 2019 visit will mark the Orchestra’s 12th tour of China—the most of any American orchestra—and will coincide with 40 years of official U.S.-China diplomatic relations. Since becoming the first American orchestra to perform in China in 1973, The Philadelphia Orchestra has developed deep, impactful connections throughout the country as a result of concerts and residencies that serve as a bridge for people-to-people exchange in culture and education. The 2019 Tour of China will begin and end with 40th anniversary concerts and residency activities in Beijing and Shanghai, the two Chinese cities that are home to the Orchestra’s longstanding partners: the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing, the Shanghai Oriental Art Center, and the Shanghai Media Group Performing Arts Division. -

Mahler's Song of the Earth

SEASON 2020-2021 Mahler’s Song of the Earth May 27, 2021 Jessica GriffinJessica SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, May 27, at 8:00 On the Digital Stage Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michelle DeYoung Mezzo-soprano Russell Thomas Tenor Mahler/arr. Schoenberg and Riehn Das Lied von der Erde I. Das Trinklied von Jammer der Erde II. Der Einsame im Herbst III. Von der Jugend IV. Von der Schönheit V. Der Trunkene im Frühling VI. Der Abschied First Philadelphia Orchestra performance of this version This program runs approximately 1 hour and will be performed without an intermission. This concert is part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. Our World Lead support for the Digital Stage is provided by: Claudia and Richard Balderston Elaine W. Camarda and A. Morris Williams, Jr. The CHG Charitable Trust Innisfree Foundation Gretchen and M. Roy Jackson Neal W. Krouse John H. McFadden and Lisa D. Kabnick The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Leslie A. Miller and Richard B. Worley Ralph W. Muller and Beth B. Johnston Neubauer Family Foundation William Penn Foundation Peter and Mari Shaw Dr. and Mrs. Joseph B. Townsend Waterman Trust Constance and Sankey Williams Wyncote Foundation SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair Nathalie Stutzmann Principal Guest Conductor Designate Gabriela Lena Frank Composer-in-Residence Erina Yashima Assistant Conductor Lina Gonzalez-Granados Conducting Fellow Frederick R. -

May Festival

1960 Eighty-seco nd Season 1961 UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor Third Concert Complete Series 332 1 Sixty-eighth Annual MAY FESTIVAL THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA WILLIAM SMITH, Assistant Conductor AARON COPLAND, Guest Conductor SOLOISTS ANSHEL BRUSILOW, Violinist LORNE MUNROE, Violoncellist SATURDAY AFTERNOON, MAY 6, 1961, AT 2 :30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Overture to Colas Bl'eugnon KABALEVSKY Orchestral Variations COPLAND Conducted by the composer Concerto in A minor, for Violin and Violoncello, Op. 102 BRAHMS Allegro Andante Vivace non tl'OPPO ANSHEL BRUSILOW and LORNE MUNROE IN TERMISSION Suite from The Tendel' Land COPLAND Introduction and Love Music Party Scene Finale: The Promise of Living Conducted by the composer *Suite No.2 from the Ballet, Daphnis and Chloe RAVEL Daybreak Pantomime General Dance *C 011l1nbia Records The Stein way is the official piano 0/ the University Mllsical Society. The Baldwin. Piano is the officia l piano of the Philadelphia Orchestra. A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS 1961 - UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY CONCERTS - 1962 Choral Union Series GEORGE LONDON, Bass Wednesday, October 4 THE ROGER WAGNER CHORALE Thursday, October 19 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 2:30, Sunday, October 22 CHARLES MUNCH, Conductor BERLIN PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Friday, November 3 HERBERT VON KARAJAN, Conductor *BAYANIHAN (Philippine Songs and Dances) Monday, November 6 YEHUDI MENUHIN, Violinist 2:30, Sunday, November 12 GALIN A VISHNEVSICAYA, Soprano . Tuesday, November 21 EMIL GILELS, Pianist . Tuesday, February 13 MINNEAPOLIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 2:30, Sunday, March 4 STANISLAW SKROWACZEWSKI, Conductor *AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE Saturday, March 24 Season Tickets: $20.00-$17.00-$15.00-$12.00-$10.00 Extra Series *MAZOWSZE (Polish Songs and Dances) Tuesday, October 24 THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA Thursday, November 16 GEORGE SZELL, Conductor RUDOLF SERICIN, Pianist . -

Season 2015-2016 the Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, February 18, At

Season 2015-2016 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, February 18, at 8:00 Friday, February 19, at 2:00 Saturday, February 20, at 8:00 Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Ives “Decoration Day,” from A Symphony: New England Holidays Brahms Serenade No. 2 in A major, Op. 16 I. Allegro moderato II. Scherzo: Vivace III. Adagio non troppo IV. Quasi menuetto V. Rondo: Allegro Intermission Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17 (“Little Russian”) I. Andante sostenuto—Allegro vivo II. Andantino marziale, quasi moderato III. Scherzo and Trio: Allegro molto vivace IV. Finale: Moderato assai—Allegro—Presto This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. The February 18 concert is sponsored by Daniel K. Meyer, M.D. The February 19 concert is sponsored by Peter A. Benoliel and Willo Carey. The February 20 concert is sponsored by Judy and Peter Leone. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. Michael Tilson Thomas is music director of the San Francisco Symphony, founder and artistic director of the New World Symphony, and principal guest conductor of the London Symphony. He made his Philadelphia Orchestra debut in 1971 and returns to lead the ensemble in March 2017. Born in Los Angeles, he is the third generation of his family to follow an artistic career. He began his formal studies at USC where he studied piano and conducting and composition. At 19 he was named music director of the Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra. During this same period he was pianist and conductor for Gregor Piatigorsky and Jascha Heifetz. -

N E W S R E L E a S E

N E W S R E L E A S E FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DATE: July 19, 2016 Kensho Watanabe Appointed Assistant Conductor of The Philadelphia Orchestra Aram Demirjian to lead select Family and School Concerts in 2016-17 Season (Philadelphia, July 19, 2016)—Kensho Watanabe has been named assistant conductor of The Philadelphia Orchestra, beginning in the 2016-17 season, succeeding Lio Kuokman, whose term ends at the end of the 2015-16 season. The two-year appointment includes conducting select concerts, participating in residency, touring, and educational activities, and serving as a cover conductor. The assistant conductor position also provides assistance to Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin on artistic matters in preparation for and during rehearsals, as well as assisting visiting guest conductors. Watanabe joins the distinguished conducting roster of The Philadelphia Orchestra, including Principal Guest Conductor Stéphane Denève and Conductor-in-Residence Cristian Măcelaru. “The Philadelphia Orchestra is proud to support and develop the best conducting talent, providing a broad array of artistic experiences and community engagement opportunities,” said Orchestra President and CEO Allison Vulgamore. “We have full confidence that Kensho will flourish in this role and contribute meaningfully to the music and culture of Philadelphia.” “Kensho Watanabe's appointment is the result of a highly involved audition process both on and off the podium with the musicians of The Philadelphia Orchestra, and we are delighted to work with him in his role as assistant conductor,” said Yumi Kendall, Orchestra assistant principal cello and the chair of the Musicians’ Artistic Committee. “His sincere sense of personal and musical growth aligns with how we identify as a group of artists, and we look forward to our collaborations ahead. -

The Philadelphia Orchestra

The Philadelphia Orchestra 2019–20 Season The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the world’s preeminent orchestras. It strives to share the transformative power of music with the widest possible audience, and to create joy, connection, and excitement through music in the Philadelphia region, across the country, and around the world. Through innovative programming, robust educational initiatives, and commitment to the community, the ensemble is on a path to create an expansive future for classical music, and to further the place of the arts in an open and democratic society. Artistic Leadership Yannick Nézet-Séguin is now in his eighth season as the eighth music director of The Philadelphia Orchestra. He joins a remarkable list of music directors spanning the Orchestra’s 119 seasons: Fritz Scheel, Carl Pohlig, Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy, Riccardo Muti, Wolfgang Sawallisch, and Christoph Eschenbach. Under this superb guidance The Philadelphia Orchestra has represented an unwavering standard of excellence in the world of classical music—and it continues to do so today. Yannick’s connection to the musicians of the Orchestra has been praised by both concertgoers and critics, and he is embraced by the musicians of the Orchestra, audiences, and the community. Your Philadelphia Orchestra Your Philadelphia Orchestra takes great pride in its hometown, performing for the people of Philadelphia year-round, from Verizon Hall to community centers, classrooms to hospitals, and over the airwaves and online. The Orchestra continues to discover new and inventive ways to nurture its relationship with loyal patrons. The Kimmel Center, for which the Orchestra serves as the founding resident company, has been the ensemble’s home since 2001. -

Program Notes | Michael Tilson Thomas Conducts

27 Season 2017-2018 Thursday, March 1, at 7:30 Friday, March 2, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, March 3, at 8:00 Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Measha Brueggergosman Soprano Tilson Thomas Four Preludes on Playthings of the Wind First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Mikaela Bennett, vocalist Kara Dugan, vocalist Intermission Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 (“Pathétique”) I. Adagio—Allegro non troppo II. Allegro con grazia III. Allegro molto vivace IV. Adagio lamentoso This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. The March 1 concert is sponsored by the Hassel Foundation. The March 1 concert is also sponsored by Constance Smukler. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 28 Please join us following the March 2 and 3 concerts for a free Organ Postlude with Peter Richard Conte. Rachmaninoff/ Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3, No. 2 transcr. Lemare Widor from Symphonie gothique, Op. 70: II. Andante sostenuto Karg-Elert Chorale Improvisation on “Nearer My God, to Thee” The Organ Postludes are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. 29 ®™ Getting Started with LiveNote » Please silence your phone ringer. » Download the app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store by searching for LiveNote. » Join the LiveNote Wi-Fi network from your phone. The wireless network LiveNote should appear in the list available to you.