European Red List of Reptiles Compiled by Neil A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Miocene Fossils of Lacerta Cf. Trilineata (Squamata, Lacertidae) with A

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/612572; this version posted April 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. The first Miocene fossils of Lacerta cf. trilineata (Squamata, Lacertidae) with a comparative study of the main cranial osteological differences in green lizards and their relatives Andrej Čerňanský1,* and Elena V. Syromyatnikova2, 3 1Department of Ecology, Laboratory of Evolutionary Biology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University in Bratislava, Mlynská dolina, 84215, Bratislava, Slovakia 2Borissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya 123, 117997 Moscow, Russia 3Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab., 1, St. Petersburg, 199034 Russia * Email: [email protected] Running Head: Green lizard from the Miocene of Russia Abstract We here describe the first fossil remains of a green lizardof the Lacerta group from the late Miocene (MN 13) of the Solnechnodolsk locality in southern European Russia. This region of Europe is crucial for our understanding of the paleobiogeography and evolution of these middle-sized lizards. Although this clade has a broad geographical distribution across the continent today, its presence in the fossil record has only rarely been reported. In contrast to that, the material described here is abundant, consists of a premaxilla, maxillae, frontals, bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/612572; this version posted April 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Acanthodactylus Harranensis

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T164562A5908003 Acanthodactylus harranensis Assessment by: Yakup Kaska, Yusuf Kumlutaş, Aziz Avci, Nazan Üzüm, Can Yeniyurt, Ferdi Akarsu, Roberto Sindaco View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Yakup Kaska, Yusuf Kumlutaş, Aziz Avci, Nazan Üzüm, Can Yeniyurt, Ferdi Akarsu, Roberto Sindaco. 2009. Acanthodactylus harranensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009: e.T164562A5908003. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T164562A5908003.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, -

Ship Rats and Island Reptiles: Patterns of Co-Existence in the Mediterranean

Ship rats and island reptiles: patterns of co-existence in the Mediterranean Daniel Escoriza GRECO, University of Girona, Girona, Girona, Spain ABSTRACT Background. The western Mediterranean archipelagos have a rich endemic fauna, which includes five species of reptiles. Most of these archipelagos were colonized since early historic times by anthropochoric fauna, such as ship rats (Rattus rattus). Here, I evaluated the influence of ship rats on the occurrence of island reptiles, including non-endemic species. Methodology. I analysed a presence-absence database encompassing 159 islands (Balearic Islands, Provence Islands, Corso-Sardinian Islands, Tuscan Archipelago, and Galite) using Bayesian-regularized logistic regression. Results. The analysis indicated that ship rats do not influence the occurrence of endemic island reptiles, even on small islands. Moreover, Rattus rattus co-occurred positively with two species of non-endemic reptiles, including a nocturnal gecko, a guild considered particularly vulnerable to predation by rats. Overall, the analyses showed a very different pattern than that documented in other regions of the globe, possibly attributable to a long history of coexistence. Subjects Biodiversity, Biogeography, Conservation Biology, Ecology, Zoology Keywords Alien species, Co-occurrences, Extinction, Island endemic, Lizard INTRODUCTION The Mediterranean basin is a hotspot of biodiversity, but it is also one of the regions Submitted 19 November 2019 Accepted 28 February 2020 in which biodiversity is most threatened, specifically by the massive transformation of Published 19 March 2020 landscapes and the spread of alien species (Médail & Quézel, 1999). The loss of biodiversity Corresponding author in the region began in ancient times, shortly after human colonization of the islands (Vigne, Daniel Escoriza, 1992). -

Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Herpetology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1993 Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A. Somma Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Somma, Louis A., "Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska?" (1993). Papers in Herpetology. 11. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Herpetology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. @ o /' number , ,... :S:' .' ,. '. 1'1'13 Do Mono Li ••rel,. Occur ill 1!I! ..br .... l< .. ? by Louis A. Somma Department of- Zoology University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Amphisbaenids, or worm lizards, are a small enigmatic suborder of reptiles (containing 4 families; ca. 140 species) within the order Squamata, which include~ the more speciose lizards and snakes (Gans 1986). The name amphisbaenia is derived from the mythical Amphisbaena (Topsell 1608; Aldrovandi 1640), a two-headed beast (one head at each end), whose fantastical description may have been based, in part, upon actual observations of living worm lizards (Druce 1910). While most are limbless and worm-like in appearance, members of the family Bipedidae (containing the single genus Sipes) have two forelimbs located close to the head. This trait, and the lack of well-developed eyes, makes them look like two-legged worms. -

Environmental, Socioeconomic and Cultural Heritage Baseline Page 2 of 382 Area Comp

ESIA Albania Section 6 – Environmental, Socioeconomic and Cultural Heritage Baseline Page 2 of 382 Area Comp. System Disc. Doc.- Ser. Code Code Code Code Type No. Project Title: Trans Adriatic Pipeline – TAP AAL00-ERM-641-Y-TAE-1008 ESIA Albania Section 6 - Environmental, Document Title: Rev.: 03 Socioeconomic and Cultural Heritage Baseline TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIOECONOMIC AND CULTURAL HERITAGE BASELINE 11 6.1 Introduction 11 6.2 Offshore Biological and Physical Environment 11 6.2.1 Introduction 11 6.2.2 Geographical Scope of the Baseline 13 6.2.3 Methodology and Sources of Information 13 6.2.3.1 Video Methodology 13 6.2.3.2 Environmental Survey Methodology 13 6.2.4 Legislation 15 6.2.4.1 Designated Sites 15 6.2.4.2 Sensitive and Protected Habitats / Biocenoses 16 6.2.5 Regional Overview 16 6.2.5.1 Introduction 16 6.2.5.2 Physical Environment 16 6.2.5.3 Biological Baseline 33 6.2.6 Albanian Nearshore Study Area 56 6.2.6.1 Physical Baseline 56 6.2.6.2 Biological Baseline 69 6.3 Offshore Socioeconomic Environment 73 6.3.1 Introduction 73 6.3.2 Harbours 75 6.3.2.1 Durrës Harbour 75 6.3.2.2 Vlorë Port 76 6.3.3 Marine Traffic 76 6.3.3.1 Ferry Traffic 79 6.3.4 Fishing 80 6.3.4.1 National Overview 80 6.3.5 Cultural Heritage 87 6.3.6 Marine Ammunition / Unexploded Ordnances (UXO) 88 6.4 Onshore Physical Environment 89 6.4.1 Climate and Ambient Air Quality 89 6.4.1.1 Overview 89 6.4.1.2 Climate 89 6.4.1.3 Wind 99 6.4.1.4 Ambient Air Quality 103 6.4.1.5 Key Findings and Conclusions 107 6.4.1.6 Limitations 108 6.4.2 Acoustic Environment 108 6.4.2.1 Acoustic Environment along the Pipeline Route 108 6.4.2.2 Acoustic Environment at CS03 112 6.4.2.3 Acoustic Environment at CS02 116 6.4.2.4 Limitations 120 6.4.3 Surface Water 120 6.4.3.1 Introduction 120 6.4.3.2 River Hydro-Morphology 121 6.4.3.3 Water Quality 127 6.4.3.4 Sediment Quality 137 6.4.3.5 Key Findings and Conclusions 141 Page 3 of 382 Area Comp. -

The Red List of Italian Animals

Home / Life/ Special Reports The Red List of Italian animals Biodiversity in Italy Italy has a rich biodiversity due to its distinctive geographic, climatic and historical characteristics. In particular, there is an enormous variety of endemic species, i.e. those plant and animal species that can be found exclusively in a given territory. In Italy, we can find approximately one third of the European animals and one half of the plants, even though its surface area is not so vast, when compared to the whole of Europe. The Italian sea has an even more rich biodiversity, because most of the species that are typical of the Mediterranean Sea live in its waters. All this makes Italy a “hot spot” for biodiversity, which is recognized all over the world. The Red List The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization that is concerned with the conservation of biodiversity and has introduced the Red Lists. The Red Lists, therefore, are able to assess the risk of extinction of the species, and can, consequently carry out the correct actions to contrast the factors that threaten the loss of biodiversity. 672 species of vertebrates (576 terrestrial and 96 marine) have been assessed, out of which 6 species have become extinct in recent times. It has been assessed that 28% of the species are threatened with extinction, 138 terrestrial species and 23 marine species). Instead 50% of the species of Italian vertebrates are not in imminent risk of extinction. According to recent studies it appears that the marine species are declining more rapidly than the terrestrial species. -

Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians

Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians Compiled by Terbish, Kh., Munkhbayar, Kh., Clark, E.L., Munkhbat, J. and Monks, E.M. Edited by Munkhbaatar, M., Baillie, J.E.M., Borkin, L., Batsaikhan, N., Samiya, R. and Semenov, D.V. ERSITY O IV F N E U D U E T C A A T T S I O E N H T M ONGOLIA THE WORLD BANK i ii This publication has been funded by the World Bank’s Netherlands-Mongolia Trust Fund for Environmental Reform. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colours, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The World Conservation Union (IUCN) have contributed to the production of the Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians, providing technical support, staff time, and data. IUCN supports the production of the Summary Conservation Action Plans for Mongolian Reptiles and Amphibians, but the information contained in this document does not necessarily represent the views of IUCN. Published by: Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY Copyright: © Zoological Society of London and contributors 2006. -

Origin of Tropical American Burrowing Reptiles by Transatlantic Rafting

Biol. Lett. in conjunction with head movements to widen their doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0531 burrows (Gans 1978). Published online Amphisbaenians (approx. 165 species) provide an Phylogeny ideal subject for biogeographic analysis because they are limbless (small front limbs are present in three species) and fossorial, presumably limiting dispersal, Origin of tropical American yet they are widely distributed on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean (Kearney 2003). Three of the five burrowing reptiles by extant families have restricted geographical ranges and contain only a single genus: the Rhineuridae (genus transatlantic rafting Rhineura, one species, Florida); the Bipedidae (genus Nicolas Vidal1,2,*, Anna Azvolinsky2, Bipes, three species, Baja California and mainland Corinne Cruaud3 and S. Blair Hedges2 Mexico); and the Blanidae (genus Blanus, four species, Mediterranean region; Kearney & Stuart 2004). 1De´partement Syste´matique et Evolution, UMR 7138, Syste´matique, Evolution, Adaptation, Case Postale 26, Muse´um National d’Histoire Species in the Trogonophidae (four genera and six Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France species) are sand specialists found in the Middle East, 2Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State North Africa and the island of Socotra, while the University, University Park, PA 16802-5301, USA largest and most diverse family, the Amphisbaenidae 3Centre national de se´quenc¸age, Genoscope, 2 rue Gaston-Cre´mieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France (approx. 150 species), is found on both sides of the *Author and address for correspondence: De´partment Syste´matique et Atlantic, in sub-Saharan Africa, South America and Evolution, UMR 7138, Syste´matique, Evolution, Adoptation, Case the Caribbean (Kearney & Stuart 2004). -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Evolution of Limblessness

Evolution of Limblessness Evolution of Limblessness Early on in life, many people learn that lizards have four limbs whereas snakes have none. This dichotomy not only is inaccurate but also hides an exciting story of repeated evolution that is only now beginning to be understood. In fact, snakes represent only one of many natural evolutionary experiments in lizard limblessness. A similar story is also played out, though to a much smaller extent, in amphibians. The repeated evolution of snakelike tetrapods is one of the most striking examples of parallel evolution in animals. This entry discusses the evolution of limblessness in both reptiles and amphibians, with an emphasis on the living reptiles. Reptiles Based on current evidence (Wiens, Brandley, and Reeder 2006), an elongate, limb-reduced, snakelike morphology has evolved at least twenty-five times in squamates (the group containing lizards and snakes), with snakes representing only one such origin. These origins are scattered across the evolutionary tree of squamates, but they seem especially frequent in certain families. In particular, the skinks (Scincidae) contain at least half of all known origins of snakelike squamates. But many more origins within the skink family will likely be revealed as the branches of their evolutionary tree are fully resolved, given that many genera contain a range of body forms (from fully limbed to limbless) and may include multiple origins of snakelike morphology as yet unknown. These multiple origins of snakelike morphology are superficially similar in having reduced limbs and an elongate body form, but many are surprisingly different in their ecology and morphology. This multitude of snakelike lineages can be divided into two ecomorphs (a are surprisingly different in their ecology and morphology. -

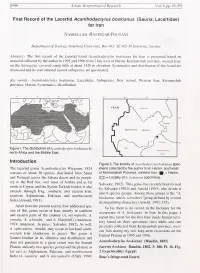

Sauria: Lacertidae) for Iran

1999 Asiatic Herpetological Research Vol. 8, pp. 85-89 First Record of the Lacertid Acanthodactylus boskianus (Sauria: Lacertidae) for Iran Nasrullah Rastegar-Pouyani Department of Zoology, Goteborg University. Box 463, SE 405 30 Goteborg, Sweden Abstract.- The first record of the lacertid li/.ard Acanthodactylus boskianus for Iran is presented based on material collected by the author in 1995 and 1996 from 2 km west of Harsin, Kermanshah province, western Iran, on the Astragalus -covered sandy hills at about 1420 m elevation. Systematics and distribution of this lizard are discussed and its conventional known subspecies are questioned. Key words.- Acanthodactylus boskianus, Lacertidae, Subspecies, New record. Western Iran, Kermanshah province, Harsin, Systematics, Distribution. Figurel . The distribution of Acanthodactylus boskianus in north Africa and the Middle East. Introduction Figure 2. The locality of Acanthodactylus boskianus spec- The lacertid genus Acanthodactylus Wiegman, 1834 imens collected by the author from Harsin, southeast of Kermanshah western Iran. = consists of about 30 species, distributed from Spain Province, (|) Harsin, = and Portugal across the Sahara desert and its periph- () Locality of A. boskianus specimens. ery to the Red Sea, over most of Arabia and as far Salvador. 1982). This genus has recently been revised north as Cyprus and the Syrian-Turkish border; it also by Salvador (1982) and Arnold (1983) who divide it extends through Iraq, southern, and eastern Iran, into 9 species groups. Among these groups is the "A. southern Afghanistan. Pakistan and northwestern boskianus and A. schreiberi "group defined by several India (Arnold, 1983). distinguishing characters (Arnold, 1983: 315). Apart from the present record, four additional spe- So far, there is no record in the literature for the cies of this genus occur in Iran, mainly in southern occurrence of A. -

A Brief History of Greek Herpetology

Bonn zoological Bulletin Volume 57 Issue 2 pp. 329–345 Bonn, November 2010 A brief history of Greek herpetology Panayiotis Pafilis 1,2 1Section of Zoology and Marine Biology, Department of Biology, University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, Ilissia 157–84, Athens, Greece 2School of Natural Resources & Environment, Dana Building, 430 E. University, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI – 48109, USA; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract. The development of Herpetology in Greece is examined in this paper. After a brief look at the first reports on amphibians and reptiles from antiquity, a short presentation of their deep impact on classical Greek civilization but also on present day traditions is attempted. The main part of the study is dedicated to the presentation of the major herpetol- ogists that studied Greek herpetofauna during the last two centuries through a division into Schools according to researchers’ origin. Trends in herpetological research and changes in the anthropogeography of herpetologists are also discussed. Last- ly the future tasks of Greek herpetology are presented. Climate, geological history, geographic position and the long human presence in the area are responsible for shaping the particular features of Greek herpetofauna. Around 15% of the Greek herpetofauna comprises endemic species while 16% represent the only European populations in their range. THE STUDY OF REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS IN ANTIQUITY Greeks from quite early started to describe the natural en- Therein one could find citations to the Greek herpetofauna vironment. At the time biological sciences were consid- such as the Seriphian frogs or the tortoises of Arcadia. ered part of philosophical studies hence it was perfectly natural for a philosopher such as Democritus to contem- plate “on the Nature of Man” or to write books like the REPTILES AND AMPHIBIANS IN GREEK “Causes concerned with Animals” (for a presentation of CULTURE Democritus’ work on nature see Guthrie 1996).