New Evidence for a First Century Roman Fort at Longtown Castle, Herefordshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gateway Monmouth January 2014

GATEWAY MONMOUTH JANUARY 2014 design + access statement design+access statement : introduction Gateway Monmouth Contents introduction 8.10 Archaeology Desktop Review 15.0 Final Design Proposals 1.0 Executive Summary 8.11 Land Ownership & Maintenance 15.1 Overall Plan 2.0 Purpose of Study 15.2 Long Sections 3.0 Design Team collaboration 15.3 Montage Views 9.0 Community & Stakeholder Engagement 16.0 Character policy context 10.0 Statutory Authorities 16.1 Hard Landscape 4.0 Planning Policy Context 10.1 Planning 16.2 Soft Landscape 4.1 National 10.2 Highways 16.3 The Square 4.2 Local 10.3 Environment Agency 16.4 The Riverside 10.4 CADW 16.5 Blestium Street vision 16.6 Amenity Hub Building 16.7 Street Furniture 5.0 Objectives assessing design issues 11.0 Opportunities & Constraints 16.8 Public Art Strategy 17.0 Community Safety appraisal 11.1 Opportunities 17.1 Lighting Strategy 6.0 Site Context 11.2 Constraints 17.2 Integrated Flood Defence 6.1 Regional Context 12.0 Key Design Issues & Drainage Strategy 6.2 Local Context 12.1 Allotment Access 18.0 Environmental Sustainability 7.0 Historic Context 12.2 Flood Defence 18.1 Landscape Design 7.1 Monmouth 12.3 Access to the River Edge 18.2 Building Design 7.2 Site History 12.4 Building Location 19.0 Access & Movement 8.0 Site Appraisal 12.5 Coach Drop-Off 19.1 Movement Strategy 8.1 Local Character 12.6 Blestium Street 19.2 Allotments Access & 8.2 Current Use 13.0 Conservation Response Canoe Platform 8.3 Key Views & Landmarks 19.3 Car Parking 8.4 The Riverside detailed design 19.4 Landscape Access 8.5 Access 14.0 Design Development Statement 8.6 Movement 14.1 Design Principles 8.7 Microclimate 14.2 Design Evolution appendices 8.8 Geotechnical Desktop Study 14.3 Design Options i. -

July Gorffennaf

EventS PROGRAMME RHAGLEN July Monmouth CarNival and 22-30 Gorffennaf Fringe Events Programme 9 days of free festival • Gŵyl Rad am 9 ddiwrnod Included www.monmouthfestival.co.uk STONE & MORE — Since — SUMMER MANDARIN STONE SALE JUNE JULY now on Order online at: mandarinstone.com or visit your local showroom: Unit , Wonastow Industrial Estate East, Monmouth, NP JB Excludes Classic and Discontinued lines. Cannot be used in conjunction with any other o er. 2 STONE & MORE — Since — WELCOME TO MONMOUTH FESTIVAL 2016 What started as a seed of an idea by a group of Monmouth friends is still going strong 35 years later. In 2016 the annual Monmouth Festival, one of the largest free festivals in Europe, is taking place a week earlier than SUMMER normal so that it doesn’t clash with the National Eisteddfod. rganised totally by a committee of volunteers, plans This is a free festival and to ensure that it continues, we rely for this year’s event started in September 2015 on our audience to support local shops, on-site traders and culminating in a full programme of entertainment above all, to give generously to the bucket collections. Oto hopefully cover all tastes. Last year the festival We are always ready to welcome new members to our festival became a glass free zone and your response to our request family. If you would like to help the festival in the future, either was fantastic. Please can we ask for your support again. on the committee or as a volunteer, please contact us via our A requirement of our licence is that only plastic bottles and website www.monmouthfestival.co.uk or email us at cans are welcome. -

T Hls Is a Maritime Eounty, Bounded on Tle South-East by the River

• • THlS is a maritime eounty, bounded on tLe south-east by the river Severn, on the south by the Bristol Channel, on tlw west by the counties of Glamorgan and Brecknock (in South Wales), on the north by part of the latter county and Herefordshire, and on the east by Gloucestershire, from which it is separated by the river \Vye. Its greatest length, from north to south, is thirty miles; its breadth, from east to west, twenty-six square miles; and its cil'cumferenco about one hnndred and ten miles, comprising an area of -±96 miles, or 317,4,10 statute acres. In size it ranks as tho thir~y sixth English county. NaME AND EaRLY HISTORY. By the Saxons this county was denomimated Tf/entsel and TVentdand; but by the Britons it was cttllod Gwent, from an ancient city of thrrt name. The modern ape.t.ation is taken from 1\Ionmo'Ith, the county town, which Leland derives from its situation between the river Monnow (or l\llmnow) and the \Vye; Ua'ntlen also says it was originally ca11ed Jllon_qwy (Mwny). 'l'he ancient inllabitants of this and tlle neigltbonri1•g county of Hereford W• re the Silu1·es ; and the early history of 1Ionmouthshire partahs of the events which took place iu tlle former county, and Jf those which occurred in Iluntin;;donshire. The Romans occnpieJ the country of the SiluTes, as a con quered province, from their complete establishment in the reign of Vesp1.sian to the period of their final depwture from Britain, when the colossal empire of Rome was tottering to its centre. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 2 PROGRAMME – WINTER – JULY TO DECEMBER 1978 .................................................... 3 FIELD MEETING AT LONGTOWN AND CRASSWALL, 19TH MARCH, 1978 ....................... 4 THE GRANDMONTINE PRIORY OF ST MARY AT CRASWALL.......................................... 5 LONGTOWN CASTLE ........................................................................................................ 10 IN SEARCH OF ST ETHELBERT’S WELL, HEREFORD .................................................... 14 NOTES ON MILLS FROM ESTATE LEDGERS .................................................................. 16 EXCAVATIONS AT THE COUNTY HOSPITAL, BURIAL GROUND OF ST GUTHLAC’S MONASTERY – MAY 1978 ................................................................................................. 16 EWYAS HAROLD ............................................................................................................... 17 FORGE GARAGE, WORMBRIDGE .................................................................................... 20 MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE ELECTED FOR 1978 ................................................... 23 ACTIVITIES OF OTHER SOCIETIES ................................................................................. 23 HAN 35 Page 1 HEREFORDSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL NEWS WOOLHOPE CLUB ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SECTION No. 35 June 1978 EDITORIAL Many members will probably have seen photographs of -

Annual Report 2017-18

Monmouth Town Council Cyngor Tref Trefynwy Annual Report 2017/2018 Shire Hall Tel: 01600 715665 Agincourt Square Monmouth Email: [email protected] NP25 3DY www.monmouth.gov.uk 1 Final Version 09/08/18 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................... 3 The Council Team .............................................................................................. 4 Councillors ...................................................................................................... 4 Officers of the Town Council ........................................................................... 5 Committee Meetings of the Council .................................................................. 6 Working Groups of the Town Council ................................................................ 7 Finances ............................................................................................................. 8 Allocation of expenditure 2017/18 ................................................................. 8 Monmouth Town Council’s Mission: The Values and Objectives ....................... 9 The Well-Being Goals ....................................................................................... 10 Representation on Outside Bodies 2017/18 .................................................... 11 Core Working Groups of the Town Council 2017/18 ........................................ 12 The Planning Committee ............................................................................. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Abergavennyvisit the Mayor’S Welcome

AbergavennyVISIT The Mayor’s Welcome I am very proud of my town. As a gentleman visitor For the more active we have the mountains of the said to me a few weeks ago “ Abergavenny is the best Blorenge, Sugar Loaf, Rholben and Skirrid and the town of its size, not only in Wales, but throughout Great Brecon and Monmouth Canal, where one can either hire Britain”. a boat or enjoy leisurely walks along the towpath. Many people tell me how friendly it is and how they Further afield there are many places of interest to visit, enjoy the interesting aspects of the town. several castles and Llanthony Abbey. Various activities such as pony trekking, hang gliding and fishing. The Castle and Museum, St Mary’s Church, Priory and Tithe barn with their wealth of history. We are so lucky to live here and we hope to encourage many visitors to share our bounty. The Market Hall and Brewery Yard with their different markets throughout the week. Cllr. Maureen Powell Mayor of Abergavenny Those wishing for a stroll can enjoy Bailey Park, Linda Vista gardens and the beautiful Castle Meadows with the river Usk flowing by. The Abergavenny Tourist Information Centre The Tithe Barn, Monk Street, Abergavenny NP7 5ND Tel: 01873 853254 Email: [email protected] As a fully networked ‘Visit Wales’ Centre, the centre offers a full range of services including the Bed Booking service both locally and nationally and a wide range of free literature about Wales, adjoining areas of England and the National Park. Friendly helpful staff are on hand to help with public transport enquiries, detailed walking advice and local attractions. -

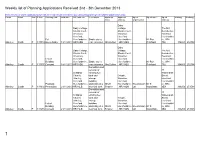

Planning Applications Received 2 to 8 December 2013

Weekly list of Planning Applications Received 2nd - 8th December 2013 Direct Access to search application page click here http://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/housing/planning/searchplanningapplications.aspx Parish Ward Unit Ref no Planning code Valid date Site address Description Applicant Applicant Agent Agent name Agent Easting Northing name address Organisation address Dairy Dairy Cottage, Cottage, The Mill, Stocks Court, Stocks Court, Kenchester, Woonton, Woonton, Hereford, Hereford, Hereford, Herefordshi Full Herefordshire, Single storey Herefordshire Mr Ron re, HR4 Almeley Castle P 133054 Householder 18/11/2013 HR3 6QU rear extension. Mrs Bufton , HR3 6QU Pritchard 7QJ 334653 252794 Dairy Dairy Cottage, Cottage, The Mill, Stocks Court, Stocks Court, Kenchester, Woonton, Woonton, Hereford, Listed Hereford, Hereford, Herefordshi Building Herefordshire, Single storey Herefordshire Mr Ron re, HR4 Almeley Castle P 133055 Consent 18/11/2013 HR3 6QU rear extension. Mrs Bufton , HR3 6QU Pritchard 7QJ 334653 252794 Demolition and removal of 41 St Marys existing fuel Widemarsh Church, tank and Crispin, Street, Almeley, storage Woonton, Hereford, Hereford, building Hereford, Herefordshi Planning Herefordshire, and;siting of a Mrs E Herefordshire Hook Mason Mr S re, HR4 Almeley Castle P 133032 Permission 21/11/2013 HR3 6LB new fuel tank. Shayler , HR3 6QN Ltd Napolitano 9EA 333256 251508 Demolition and removal of 41 St Marys existing fuel Widemarsh Church, tank and Crispin, Street, Almeley, storage Woonton, Hereford, Listed Hereford, building Hereford, -

Newsletter Articles Index

Abergavennny Local History Society Newsletters 1985 to date Issue Year Page no Title Author 1 1985 1 Introduction to Newsletter 1 Abergavenny Street Survey 2 Plaques 2 Summer visits 1986 2 Floodlighting 3 British Association for Local history Award 3 Members Photographic Comprtition 1985 3 Lecture Programme 1985-1986 3 Officers 2 1986 2 Forward 2 Lecture Programme 1986-1987 2 Officers 3 Summer visits 1986 3 A Question Answered ? (Manorbier Church) Arthur Fleet 4 Life in the Workhouse to Life in the Big House 5 News from Abergavenny Museum 5 Castle Floodlighting Sponsors 5 Members Photographic Comprtition 1986 3 1987 2 Mediaeval Bits and Pieces Committee member 2 - Heraldry Committee member 2 - Castle assault Committee member 2 - Chemical Warfare Committee member 2 - Salt Committee member 2 - The Old and New Testaments Committee member 2 - Chantry Committee member 2 - Animals Committee member 3 - Emblems and Evangelists Committee member 3 Summer visits 1987 Alan Spink 3 St Johns Church and Grammar School Committee member 4 Inconsequential Musings Gwyn Smith 4 Eisteddfodau Committee member 5 Members Photographic Comprtition 1987 6 Lecture Programme 1987-1988 6 Officers 4 1988 2 The Gunter House - Cross Street 2 Demolishing The Volunteers Hall Arthur Fleet 3 The Plaque Subcommitee 4 Summer visits 1987 Alan Spink 4 Was St Patrick born in Abergavenny Beryl Jones 5 Castle Floodlighting 5 Study Groups 5 Activities 6 Members Photographic Competition 1988 6 Lecture Programme 1988-1989 5 1989 1 Freda Key - A Tribute Gwyn Jones 1 Freda Ken Key 1 -

The Roman and the Post-Roman South

Chapter 2 The Mabinogi of Pwyll The Roman and the Post-Roman South The complex of the Indigenous Underworld, and its association with South Wales, was overlayed by the interaction of geography and history throughout the Roman and Post-Roman periods. Unlike the kingdoms of the North, Dyfed, Ystrad Twyi, Gwent, Brycheiniog, Glywissing and the other Southern Welsh kingdoms did not fall under the sway of the warrior dynasties of Coel Hen and the Votadinii (which are further discussed in Chapter 3) during the fifth and sixth century sub-Roman period. Instead, this part of Wales retained its traditional connections with Ireland on one hand, and the plains of England on the other. These are links which, as we have seen, had deep prehistoric roots, even as far back as the Early Stone Age (see p. 26, n. 34, p. 157 n. 218 above). But even into the historic period, the respective experiences of North and South Wales tended to reinforce rather than submerge their cultural differences, as we will now consider. In the first century AD, following a brief but intense period of resistance during the Claudian conquest, the Silures of what is now the south-eastern corner of Wales submitted wholeheartedly to the Roman yoke. The rich, lowland landscape of this area made it conducive to the Roman way of life. The civitas or tribal district of the Silurian people supported a thriving villa economy – as well as a number of fully-developed urban centres at Nidum (Neath), Isca (Caerleon), Gobannium (Abergevenny) and Venta Silurum (Caerwent). It was this latter location, literally meaning ‘Marketplace (venta) of the Silures’ which was to bequeath its name to the later sub-Roman kingdom of Gwent. -

Recorder-Issue 87

Worcestershire Recorder Spring 2013, Edition 87 ISSN 1474-2691 Newsletter of the WORCESTERSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Charity No 517092 Free to Members Membership Secretary Tel: 01684 578142 CONTENTS Page Chairman’s Letter … … … … … … … … … … … 3 Constitutional Changes … … … … … … … … … … … 3 WAS Committee Structure 2013-14 … … … … … … … … … 4 Welcome to new Committee members … … … … … … … … … 5 Brian Ferris, Honorary Member … … … … … … … … … … 5 News from the County: New evidence for the production of floor tile inWorcester … … 5 From Museums Worcestershire: Bredon Hill Roman Coin Hoard: a thank you … … 8 Secret Egypt: Unravelling Truth from Myth … … … 9 News from the City … … … … … … … … … … … 9 Surveying buildings at risk in Worcester … … … … … … … … 10 History West Midlands … … … … … … … … … … … 10 David Whitehouse 1941-2013 … … … … … … … … … … 10 Recent Publications: The Battle of Worcester 1651 … … … … … … … 11 Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture. X. The Western Midlands 15 Monastic Charity & the office of Almoner at Worcester … … … 18 Ariconium, Herefordshire … … … … … … … 20 Wellington Quarry, Herefordshire … … … … … … 20 The Medieval Monastery … … … … … … … 20 Malvern Women of Note … … … … … … … … 20 The Pubs of Malvern, Upton and neighbouring villages … … … 21 Having a Drink round Feckenham, Inkberrow and Astwood Bank … 21 Mystery Corner: Worcester Cathedral Altar Rails … … … … … … … 21 Postscript to Chartist notes in Recorder 86 … … … … … … … … 21 Hellens, Much Marcle … … … … … … … … … … … 21 The Feckenham Forester … … … -

Map 8 Britannia Superior Compiled by A.S

Map 8 Britannia Superior Compiled by A.S. Esmonde-Cleary, 1996 with the assistance of R. Warner (Ireland) Introduction Britain has a long tradition of antiquarian and archaeological investigation and recording of its Roman past, reaching back to figures such as Leland in the sixteenth century. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the classically-educated aristocracy and gentry of a major imperial and military power naturally felt an affinity with the evidence for Rome’s presence in Britain. In the twentieth century, the development of archaeology as a discipline in its own right reinforced this interest in the Roman period, resulting in intense survey and excavation on Roman sites and commensurate work on artifacts and other remains. The cartographer is therefore spoiled for choice, and must determine the objectives of a map with care so as to know what to include and what to omit, and on what grounds. British archaeology already has a long tradition of systematization, sometimes based on regions as in the work of the Royal Commissions on (Ancient and) Historic Monuments for England (Scotland and Wales), but also on types of site or monument. Consequently, there are available compendia by Rivet (1979) on the ancient evidence for geography and toponymy; Wacher (1995) on the major towns; Burnham (1990) on the “small towns”; Margary (1973) on the roads that linked them; and Scott (1993) on villas. These works give a series of internally consistent catalogs of the major types of site. Maps of Roman Britain conventionally show the island with its modern coastline, but it is clear that there have been extensive changes since antiquity, and that the conventional approach risks understating the differences between the ancient and the modern.