Land at Ty Mawt Holyhead Anglesey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Archaeology Wales

Archaeology Wales Proposed Hotel at Parc Cybi Enterprise Zone, Holyhead, Anglesey Heritage Impact Assessment: Trefignath Burial Chamber (SAM AN011) & Ty-Mawr Standing Stone (SAM AN012) Trefignath Burial Chamber Ty-Mawr Standing Stone Adrian Hadley Report No. 1589 Archaeology Wales Limited The Reading Room, Town Hall Great Oak Street, Llanidloes, Powys, SY18 6BN Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440319 Email: [email protected] Archaeology Wales Proposed Hotel at Parc Cybi Enterprise Zone, Holyhead, Anglesey Heritage Impact Assessment: Trefignath Burial Chamber (SAM AN011) & Ty-Mawr Standing Stone (SAM AN012) Prepared for Axis Planning Services Edited by: Adrian Hadley Authorised by: Mark Houliston Signed: Signed: Position: Heritage Consultants Position: Managing Director Date: 12/06/2017 Date: 12/06/2017 Adrian Hadley BA (Hons) MA Report No. 1589 May 2017 Archaeology Wales Limited The Reading Room, Town Hall Great Oak Street, Llanidloes, Powys, SY18 6BN Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440319 Email: [email protected] Contents Heritage Impact Statement Page 1 1. Introduction Page 3 2. Topography and Geology Page 3 3. Archaeological Background Page 4 4. Legislative Policy and Guidance Page 5 5. Methodology for a Heritage Impact Assessment Page 5 6. Methodology for Analysis of Setting Page 6 7. Development Proposals Page 11 8. Significance of Ty-Mawr Standing Stone Page 11 9. Significance of Trefignath Burial Chamber Page 12 10. Assessment of Potential Impacts Page 14 11. Measures to Offset Potential Adverse Impacts Page 16 12. Summary of Residual Impacts Page -

Parc Cybi, Holyhead

1512 Parc Cybi, Holyhead Final Report on Excavations Volume 1: Text and plates Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Parc Cybi, Holyhead Final Report on Excavations Volume 1: Text and Plates Project No. G1701 Report No. 1512 Event PRN 45467 Prepared for: Welsh Government January 2020 (corrections December 2020) Written by: Jane Kenney, Neil McGuinness, Richard Cooke, Cat Rees, and Andrew Davidson with contributions by David Jenkins, Frances Lynch, Elaine L. Morris, Peter Webster, Hilary Cool, Jon Goodwin, George Smith, Penelope Walton Rogers, Alison Sheridan, Adam Gwilt, Mary Davis, Tim Young and Derek Hamilton Cover photographs: Topsoil stripping starts at Parc Cybi Cyhoeddwyd gan Ymddiriedolaeth Achaeolegol Gwynedd Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd Craig Beuno, Ffordd y Garth, Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2RT Published by Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Craig Beuno, Garth Road, Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2RT Cadeiryddes/Chair - David Elis-Williams, MSc., CIPFA. Prif Archaeolegydd/Chief Archaeologist - Andrew Davidson, B.A., M.I.F.A. Mae Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd yn Gwmni Cyfyngedig (Ref Cof. 1180515) ac yn Elusen (Rhif Cof. 508849) Gwynedd Archaeological Trust is both a Limited Company (Reg No. 1180515) and a Charity (reg No. 508849) PARC CYBI, HOLYHEAD (G1701) FINAL REPORT ON EXCAVATIONS Event PRN 45467 Contents List of Tables ........................................................................................................................i List of Figures.......................................................................................................................i -

Plas Penmynydd, Llangefni, Anglesey, LL77 7SH

Plas Penmynydd, Llangefni, Anglesey, LL77 7SH Researched and written by Richard Cuthbertson, Gill. Jones & Ann Morgan 2019 revised 2020 HOUSE HISTORY RESEARCH Written in the language chosen by the volunteers and researchers & including information so far discovered PLEASE NOTE ALL THE HOUSES IN THIS PROJECT ARE PRIVATE AND THERE IS NO ADMISSION TO ANY OF THE PROPERTIES ©Discovering Old Welsh Houses Group Rhif Elusen Gofrestredig: Registered charity No: 1131782 Contents page 1. Building Description 2 2. Early Background History 9 3. 16 th Century 21 4. 17 th Century 24 5. 18 th Century 30 6. 19 th Century 37 7. 20 th Century 50 8. Bibliography 53 Appendices 1. The Royal House of Cunedda 54 2. The Tudors of Penmynydd 56 3. The Ancestors of Ednyfed Fychan 59 4. An Alternative Pedigree of Maredudd ap Tudor 61 5. The Will of Richard Owen Theodor IV 1645 62 6. The Will of Mary Owen 1666 63 7. The Will of Elizabeth Owen 1681 64 8. The Bulkeley Family 65 9. The Edmunds Family 68 10. The Will of Henry Hughes 1794 69 11. The Paget Family 71 Acknowledgement – With thanks for the financial support from the Anglesey Charitable Trust and Friends of Discovering Old Welsh Houses. 1 Building Description Plas Penmynydd Grade II*: listed 5/2/1952 - last amended 29/1/2002 OS Grid: SH49597520 CADW ID: 5447 NPRN: 15829 Penmynydd & Tudor Spelling variants. Benmynydd, Penmynyth, Penmynythe, Penmynydd; Tudur, Tudor, Tydder. It is very likely that the earliest houses on the site were all wooden and as yet no trace of them has been found, but the Hall House of Owain Tudur's time (1400s) can be clearly seen in the neat and regular stonework up to the first 4 feet on the North Front (the side with the big oak front door). -

Download Date 30/09/2021 08:59:09

Reframing the Neolithic Item Type Thesis Authors Spicer, Nigel Christopher Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 30/09/2021 08:59:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/13481 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Reframing the Neolithic Nigel Christopher SPICER Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Archaeological Sciences School of Life Sciences University of Bradford 2013 Nigel Christopher SPICER – Reframing the Neolithic Abstract Keywords: post-processualism, Neolithic, metanarrative, individual, postmodernism, reflexivity, epistemology, Enlightenment, modernity, holistic. In advancing a critical examination of post-processualism, the thesis has – as its central aim – the repositioning of the Neolithic within contemporary archaeological theory. Whilst acknowledging the insights it brings to an understanding of the period, it is argued that the knowledge it produces is necessarily constrained by the emphasis it accords to the cultural. Thus, in terms of the transition, the symbolic reading of agriculture to construct a metanarrative of Mesolithic continuity is challenged through a consideration of the evidential base and the indications it gives for a corresponding movement at the level of the economy; whilst the limiting effects generated by an interpretative reading of its monuments for an understanding of the social are considered. -

Chapter 9: Landscape and Visual

Penrhos Leisure Village Chapter 9: Landscape and Visual CHAPTER 9: LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL Introduction 9.1 This chapter assesses the landscape and visual impacts of the proposed development at Penrhos, Cae Glas and Kingsland. In particular, it considers the potential effects of the proposed development on the landscape character of the sites and the surrounding area, and assesses the visual impact of the proposals through the identification of sensitive visual receptors and key viewpoint locations. Refer to Figure 1 for site locations (Appendix 9.2) 9.2 The chapter describes the methods used to assess the impacts, the baseline conditions currently existing at the three sites and in the surrounding area, the potential impacts of the development, the mitigation measures required to prevent, reduce, or offset the impacts, and finally, the residual impacts. 9.3 This chapter has been written by Planit-IE Ltd, a registered practice of the Landscape Institute with considerable experience in all areas of landscape design and visual assessment. Planning Policy Context National Planning Policy Planning Policy Wales (PPW), Edition 4, (February 2011) 9.4 PPW contains current land use planning policy for Wales. It provides the policy framework for the effective preparation of local planning authorities’ development plans. PPW 4 reaffirms the need for local authorities to conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the landscape designations (AONBs and National Parks) in Wales. Paragraph 5.5.5 of PPW confirms that statutory designation does not necessarily prohibit development, but proposals for development must be carefully assessed for their effect on those natural heritage interests which the designation is intended to protect. -

Bibliography Updated 2016

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Select Bibliography Northwest Wales 2016 Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age Select Bibliography Northwest Wales - Neolithic Baynes, E. N., 1909, The Excavation of Lligwy Cromlech, in the County of Anglesey, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. IX, Pt.2, 217-231 Bowen, E.G. and Gresham, C.A. 1967. History of Merioneth, Vol. 1, Merioneth Historical and Record Society, Dolgellau, 17-19 Burrow, S., 2010. ‘Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, Anglesey: alignment, construction, date and ritual’, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, Vol. 76, 249-70 Burrow, S., 2011. ‘The Mynydd Rhiw quarry site: Recent work and its implications’, in Davis, V. & Edmonds, M. 2011, Stone Axe Studies III, 247-260 Caseldine, A., Roberts, J.G. and Smith, G., 2007. Prehistoric funerary and ritual monuments survey 2006-7: Burial, ceremony and settlement near the Graig Lwyd axe factory; palaeo-environmental study at Waun Llanfair, Llanfairfechan, Conwy. Unpublished GAT report no. 662 Davidson, A., Jones, M., Kenney, J., Rees, C., and Roberts, J., 2010. Gwalchmai Booster to Bodffordd link water main and Llangefni to Penmynydd replacement main: Archaeological Mitigation Report. Unpublished GAT report no 885 Hemp, W. J., 1927, The Capel Garmon Chambered Long Cairn, Archaeologia Cambrensis Vol. 82, 1-43, series 7 Hemp, W. J., 1931, ‘The Chambered Cairn of Bryn Celli Ddu’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 216-258 Hemp, W. J., 1935, ‘The Chambered Cairn Known As Bryn yr Hen Bobl near Plas Newydd, Anglesey’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. 85, 253-292 Houlder, C. H., 1961. The Excavation of a Neolithic Stone Implement Factory on Mynydd Rhiw, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 27, 108-43 Kenney, J., 2008a. -

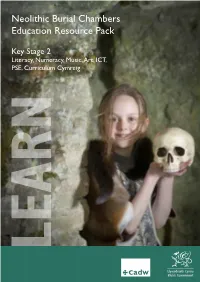

Neolithic Resource

Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource Pack Key Stage 2 Literacy, Numeracy, Music, Art, ICT, PSE, Curriculum Cymreig LEARN Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource Neolithic burial chambers in Cadw’s care: Curriculum links: Barclodiad-y-Gawres passage tomb, Anglesey Literacy — oracy, developing & presenting Bodowyr burial chamber, Anglesey information & ideas Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, Anglesey Numeracy — measuring and data skills Capel Garmon burial chamber, Conwy Music — composing, performing Carreg Coetan Arthur burial chamber, Pembrokeshire Din Dryfol burial chamber, Anglesey Art — skills & range Duffryn Ardudwy burial chamber, Gwynedd Information Communication Technology — Lligwy burial chamber, Anglesey find and analyse information; create & Parc le Breos chambered tomb, Gower communicate information Pentre Ifan burial chamber, Pembrokeshire Personal Social Education — moral & spiritual Presaddfed burial chamber, Anglesey development St Lythans burial chamber, Vale of Glamorgan Curriculum Cymreig — visiting historical Tinkinswood burial chamber, Vale of Glamorgan sites, using artefacts, making comparisons Trefignath burial chamber, Anglesey between past and present, and developing Ty Newydd burial chamber, Anglesey an understanding of how these have changed over time All the Neolithic burial chambers in Cadw’s care are open sites, and visits do not need to be booked in advance. We would recommend that teachers undertake a planning visit prior to taking groups to a burial chamber, as parking and access are not always straightforward. Young people re-creating their own Neolithic ritual at Tinkinswood chambered tomb, Vale of Glamorgan, South Wales cadw.gov.wales/learning 2 Neolithic Burial Chambers Education Resource The Neolithic period • In west Wales, portal dolmens and cromlechs The Neolithic period is a time when farming was dominate, which have large stone chambers possibly introduced and when people learned how to grow covered by earth or stone mounds. -

Land at Ty Mawr Holyhead: Archaeological Assessment And

Land at Ty Mawr Holyhead Archaeological assessment and field evaluation GAT Project G 170 I Report no. 459 June 2002 Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd Gwynedd Archaeological Trust l 'ralll 111-nno Pfordd y Garth, Bangor. Gwynedd Ll.57 2RT Contents Page nos. Introduction 1 Specification and project design 1 Methods and techniques 2 Archaeological findings and recommendations 7 Site gazetteer 11 Assessment of impact and proposals for mitigatory measures 19 Bibliography 22 Fig 1. Location of sites in proximity to study area Fig 2. Location of sites within study area Fig 3. Location of geophysical survey and trial excavation Fig 4. Penrhos 772 Estate Survey (1769): Ty Mawr farm Fig 5. Penrhos 772 Estate Survey (1769): Tyddyn Pioden Fig 6. Extract from OS 6” map 1926. Fig 7. Scheduled Area around Ty Mawr Standing stone Fig 8. Scheduled and guardianship area around Trefignath Burial Chamber Plate 1. A typical wall Plate 2. Gatepost near Trefignath Plate 3. Site 7: Well Plate 4. Site 8: Standing stone Plate 5. Site 9: Horizontal stone Plate 6. Site 14: Trefignath burial chamber Appendix 1: Project design for archaeological assessment 26 Appendix 2: Project design for archaeological evaluation 30 Appendix 3: Details of Geophysical survey 35 Fig 9. Location of Geophysical survey plots Details of geophysical survey plots (18 figures) Appendix 4: Details of Trial excavations 38 Fig 10. Location of trial excavation trenches Fig 11. Details of trenches 16 34 and 36 Fig 12. Details of Trenches 24 and 26 Fig 13. Details of trenches 51 54 and 57 Plate 7. Trench 1: wall foundation Plate 8. -

Adroddiad Yr Arolygwr (Rhan 2)

Pennod 14 – Amgylchedd 241 Pennod 14 : Amgylchedd Y Bennod Gyfan Gwrthwynebiad 80/1251 – Y Cyng Robert Llewelyn Jones 1.0 Crynodeb o’r Gwrthwynebiad 1.1 Mae angen polisi ar barciau a gerddi am nad ymddengys fod planhigion i’w gweld o amgylch trefi ac atyniadau ymwelwyr. 2.0 Ymateb y Cyngor 2.1 Nid oes a wnelo’r mater hwn â defnydd tir y gellir mynd i’r afael ag ef yn y cynllun. 3.0 Casgliad yr Arolygydd 3.1 Nid yw darparu gwaith planhigion amwynder yn fater i’r cynllun. 4.0 Argymhelliad 4.1 Na ddylid diwygio Pennod 14 y cynllun a adneuwyd mewn ymateb i’r gwrthwynebiad hwn. Nodyn: Ystyrir gwrthwynebiadau 35/1312 a 36/321 ar Dudalennau 55 i 57 yr adroddiad hwn. Y Bennod Gyfan Gwrthwynebiadau 36/327 – Asiantaeth yr Amgylchedd Cymru 14/730 – Y Gymdeithas Frenhinol er Gwarchod Adar 35/1314 ac 1315 – Cyngor Cefn Gwlad Cymru 1.0 Crynodeb o’r Gwrthwynebiadau 1.1 Mae 36/327 yn gofyn am bolisi Cadwraeth Ynni a Dðr ym Mhennod 14. Dylai cynigion datblygu, hyd y gellir, ymgorffori mesurau i gadw ynni a dðr trwy: i. lleoli a chynllunio adeiladau unigol sy’n cynnwys nodweddion arbed dðr a chynlluniau safleoedd; ii. lleihau’r angen am deithiau gan gerbydau modur preifat a; iii. defnyddio trafnidiaeth gyhoeddus. 1.2 Yn lle paragraffau 14.1 i 14.5, mae 14/730 yn mynnu y dylid gosod cyflwyniad sy’n darparu fframwaith ar gyfer y Bennod trwy nodi cynefinoedd nodedig, prin neu ddiamddiffyn Ynys Môn, yn ogystal â’r adnoddau a’r systemau naturiol allweddol. -

Exploring Geological Language in the Welsh Landscape

5 December 2016 An occasional supplement to Earth Heritage , the geological and landscape conservation publication, www.earthheritage.org.uk Exploring geological language in the Welsh landscape Elinor Gwynn, Language Heritage Officer, National Trust Cymru Following Earth Heritage items by Mick Stanley and Colin MacFadyen on Namescapes ( issue 39 ), this article tracks the way geology and geomorphology have influenced place names in Wales. Elinor was crowned at the National Eisteddfod in August 2016 for her collection of poems themed on Llwybrau (paths). How do you begin to explore the geological landscape lexis of Wales? The scope of the topic is vast, the journey complex. If place names themselves ARE our history, as Anthony Lias states in his book Place Names of the Welsh Borderlands , then surely geology has provided the backdrop against, and the stage on which centuries of history have been played out. It is the defining force that has shaped our nation, its history, language and culture. Wales has several layers of linguistic contact, as explained in the Dictionary of Place Names of Wales . Successive and overlapping periods in our history – Celtic and Brittonic, the Roman occupation, Anglo-Saxon settlement, Scandinavian invasions, Anglo-Norman conquests and English immigration, have all left their toponymic footprints. It’s worth bearing these influences in mind when attempting to interpret place names in the landscape. The language of our landscape illustrates both continuity and change in our history and culture. Names can be read in different ways; at their simplest they provide a descriptive, and often poetic portrait of the country. But those words, printed on maps and etched into memories, have shadows behind them – of past lives and livelihoods, of changing settlement patterns and shifting cultures, of socio-political struggles, and of economic fortunes and failures. -

Anglesey Beaches

Anglesey Beaches Anglesey Beaches Postcode is for sat-nav purposes only and may not represent the actual address of the beach Beach name Where Post Code Description One of Anglesey's largest and most beautiful beaches. Plenty of room for everyone to enjoy themselves Aberffraw Beach Aberffraw LL63 5EX without being on top of each other. There is a small shop in the village. Aberffraw boasts beautiful white sands and panoramic views of Snowdonia. Certainly one of Anglesey's most beautiful beaches. Winner of the European Blue Flag award since Benllech Beach Benllech LL74 8QE 2004. That should say it all. Lots of space, clean sand and ice cream parlours, a seaside shop and food available right beside the beach. Parking is available but can get very busy. Sandy rural and undeveloped beach backed by dunes, attracting windsurfers, surfers and canoeists in Cable Bay LLanfaelog LL64 5JR particular. Llanfaelog village has a selection of shops and restaurants for day trippers and families. Cemaes is a small town overlooking a picturesque sheltered bay on the far north coast of Anglesey. Cemaes Beach Cemaes LL67 0ND Within the bay and next to the town, Traeth Mawr is a sandy beach with rock pools and a promenade. There is a slipway giving access to disabled visitors. A great place for nature and bird watching, shore and kayak fishing, kayaking and rock pooling. A large Cemlyn Bay Cemaes LL67 0DU shingle ridge separates the sea from the salt and fresh water lagoon which becomes a hive of activity in the summer months when terns arrive to nest here.