Duncan2013.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2216Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150023 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘AN ENDLESS VARIETY OF FORMS AND PROPORTIONS’: INDIAN INFLUENCE ON BRITISH GARDENS AND GARDEN BUILDINGS, c.1760-c.1865 Two Volumes: Volume I Text Diane Evelyn Trenchard James A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of History of Art September, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… vi Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. viii . Glossary of Indian Terms ……………………………………………………....... ix List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………... xvii Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 1 1. Chapter 1: Country Estates and the Politics of the Nabob ………................ 30 Case Study 1: The Indian and British Mansions and Experimental Gardens of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal …………………………………… 48 Case Study 2: Innovations and improvements established by Sir Hector Munro, Royal, Bengal, and Madras Armies, on the Novar Estate, Inverness, Scotland …… 74 Case Study 3: Sir William Paxton’s Garden Houses in Calcutta, and his Pleasure Garden at Middleton Hall, Llanarthne, South Wales ……………………………… 91 2. Chapter 2: The Indian Experience: Engagement with Indian Art and Religion ……………………………………………………………………….. 117 Case Study 4: A Fairy Palace in Devon: Redcliffe Towers built by Colonel Robert Smith, Bengal Engineers ……………………………………………………..…. -

The Newhailes Armchairs England, Circa 1750

The Newhailes Armchairs England, circa 1750 General the Hon. James St. Clair General the Hon. James St. Clair (1688-1762) married Janet Dalrymple (1698-1766), the youngest daughter of Sir David Dalrymple, 1st Baronet, in 1745. Before his marriage, in 1735, he purchased Rosslyn Castle, in Midlothian, Scotland. He was sent on a special envoy to Vienna and Turin in 1748 and brought along his aides David Hume, the famous historian, and his nephew, Sir Harry Erskine. St. Clair died in 1762 and was outlived by his wife Janet, who moved to 60 Greek Street after her husband’s passing. Newhailes Sir David Dalrymple, 3rd Baronet, Lord Hailes (1726-1792) acquired the set of four chairs at the auction of the collection of Janet St. Clair, his aunt, in 1766. The set of four chairs was described as ‘4 French elbow chairs with tapestry seats & cases.’ Lord Hailes was the younger son of the 1st Viscount of Stair, President of the Court of Session and lived at Newhailes, near Edinburgh. Newhailes, now owned by the National Trust of Scotland, is an incredible survival of the Scottish Enlightenment. It was originally built by the architect James Smith (1645-1731) for his own residence, and was known as Broughton House. In 1709, Sir David Dalrymple, 1st Baronet (Janet’s father) acquired the house and renamed it Newhailes in recognition of Hailes Castle, the family estate in East Linton. The chairs were photographed in situ in the library of Newhailes in Country Life. The library was one of the most impressive spaces in the house. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 Academic Curriculum Vitae Dr. Sharon-Ruth Alker Current Position 2020 to date Chair of Division II: Humanities and Arts 2018 to date Mary A. Denny Professor of English and General Studies 2017 to date Professor of English and General Studies 2017 to 2019 Chair of the English Department, Whitman College 2010 to 2017 Associate Professor of English and General Studies Whitman College 2004 to 2010 Assistant Professor of English and General Studies Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA. Education *University of Toronto – 2003-2004 Postdoctoral Fellowship * University of British Columbia - 1998 to 2003 - PhD. English, awarded 2003 Gendering the Nation: Anglo-Scottish relations in British Letters 1707-1830 * Simon Fraser University - 1998 MA English * Simon Fraser University - 1996 BA English and Humanities Awards 2020 Aid to Scholarly Publications Award, Federation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Canadian). This is a peer-reviewed grant. For Besieged: The Post War Siege Trope, 1660-1730. 2019 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Alasdair Padman on a John Galt edition. 2018 Whitman Abshire Grant to work with student Nick Maahs on a James Hogg 2 website 2017 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Esther Ra on James Hogg’s Uncollected Works and an edition of John Galt’s Sir Andrew Wylie of that Ilk 2017 Whitman Abshire Grant to work with student Esther Ra on James Hogg’s Manuscripts 2016 Co-organized a conference that received a SSHRC Connection Grant to organize the Second World Congress of Scottish Literatures. Conference was in June 2017. 2015 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Nicole Hodgkinson on chapters of the military siege monograph. -

Drake Plays 1927-2021.Xls

Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls TITLE OF PLAY 1927-8 Dulcy SEASON You and I Tragedy of Nan Twelfth Night 1928-9 The Patsy SEASON The Passing of the Third Floor Back The Circle A Midsummer Night's Dream 1929-30 The Swan SEASON John Ferguson Tartuffe Emperor Jones 1930-1 He Who Gets Slapped SEASON Miss Lulu Bett The Magistrate Hedda Gabler 1931-2 The Royal Family SEASON Children of the Moon Berkeley Square Antigone 1932-3 The Perfect Alibi SEASON Death Takes a Holiday No More Frontier Arms and the Man Twelfth Night Dulcy 1933-4 Our Children SEASON The Bohemian Girl The Black Flamingo The Importance of Being Earnest Much Ado About Nothing The Three Cornered Moon 1934-5 You Never Can Tell SEASON The Patriarch Another Language The Criminal Code 1935-6 The Tavern SEASON Cradle Song Journey's End Good Hope Elizabeth the Queen 1936-7 Squaring the Circle SEASON The Joyous Season Drake Plays 1927-2021.xls Moor Born Noah Richard of Bordeaux 1937-8 Dracula SEASON Winterset Daugthers of Atreus Ladies of the Jury As You Like It 1938-9 The Bishop Misbehaves SEASON Enter Madame Spring Dance Mrs. Moonlight Caponsacchi 1939-40 Laburnam Grove SEASON The Ghost of Yankee Doodle Wuthering Heights Shadow and Substance Saint Joan 1940-1 The Return of the Vagabond SEASON Pride and Prejudice Wingless Victory Brief Music A Winter's Tale Alison's House 1941-2 Petrified Forest SEASON Journey to Jerusalem Stage Door My Heart's in the Highlands Thunder Rock 1942-3 The Eve of St. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

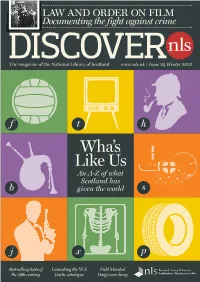

DISCOVER NLS Answer to That Question Is ‘Plenty’! Our Nation’S Issue 24 WINTER 2013 Contribution to the Rest of Mankind Is Substantial CONTACT US and Diverse

LAW AND ORDER ON FILM Documenting the fight against crime The magazine of the National Library of Scotland www.nls.uk | Issue 24 Winter 2013 f t h Wha’s Like Us An A-Z of what Scotland has b given the world s j x p Best-selling Scots of Launching the NLS Field Marshal the 19th century Gaelic catalogue Haig’s war diary WELCOME Celebrating Scotland’s global contribution What has Scotland given to the world? The quick DISCOVER NLS answer to that question is ‘plenty’! Our nation’s ISSUE 24 WINTER 2013 contribution to the rest of mankind is substantial CONTACT US and diverse. We welcome all comments, For a small country we have more than pulled our questions, submissions and subscription enquiries. weight, contributing significantly to science, economics, Please write to us at the politics, the arts, design, food and philosophy. And there National Library of Scotland address below or email are countless other examples. Our latest exhibition, [email protected] Wha’s Like Us? A Nation of Dreams and Ideas, which is covered in detail in these pages, seeks to construct FOR NLS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF an alphabetical examination of Scotland’s role in Alexandra Miller shaping the world. It’s a sometimes surprising collection EDITORIAL ADVISER Willis Pickard of exhibits and ideas, ranging from cloning to canals, from gold to Grand Theft Auto. Diversity is also at the heart of Willis Pickard’s special CONTRIBUTORS Bryan Christie, Martin article in this issue. Willis is a valued member of the Conaghan, Jackie Cromarty, Library’s Board, but will soon be standing down from that Gavin Francis, Alec Mackenzie, Nicola Marr, Alison Metcalfe, position. -

Medical Advance and Female Fame: Inoculation and Its After-Effects Isobel Grundy

Document generated on 10/02/2021 5:32 p.m. Lumen Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle Medical Advance and Female Fame: Inoculation and its After-Effects Isobel Grundy Volume 13, 1994 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1012519ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1012519ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle ISSN 1209-3696 (print) 1927-8284 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Grundy, I. (1994). Medical Advance and Female Fame: Inoculation and its After-Effects. Lumen, 13, 13–42. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012519ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle, 1994 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 2. Medical Advance and Female Fame: Inoculation and its After-Effects I intend here to examine the multiple significances whereby history is constructed.1 Argument, however, will be repeatedly hijacked by narra• tive — by, that is, a loosely linked series of epic tales which might be horribly called The Matter of Smallpox/ in whose finale the human race defeats the variola virus. -

Clarissa Campbell-Orr, in a Study Of

‘If your daughters are inclined to love reading, do not check their Inclination' Clarissa Campbell-Orr, in a study of 'womanhood in England and France 1780-1920 called Wollstonecraft's Daughters, noted the lack of research on British aristocratic women, and especially of work on 'the role of aristocratic women in advancing their children's education' (13). The themes of this conference present me with the opportunity to make a modest step towards addressing this gap, in relation to the experience of some elite Scottish women. Familial letters and memoirs are my main sources. Studies have established the importance of letters, of female epistolary networks, for understanding how women circulated ideas and disseminated their knowledge; they often reveal female views on education, and women's reading practices and experience of reading in their circle. These accounts of personal, 'lived experience' are particularly valuable. Karen Glover, in her recent excellent study, Elite Women and Polite Society in Eighteenth-Century Scotland (2011), remarks that 'when it comes to lived experience, the historiography of women's education in eighteenth-century Britain is surprisingly thin (‘a virtual desert', to quote one recent commentator), and the Scottish situation was worse.' (Glover, p. 26). In letters, Scottish women record their experiences and disseminate knowledge based on that experience in the form of advice to younger women, often family members and daughters of friends. More attention is now being paid to women's memoirs too. Karen Glover has argued that it 'was in family memoirs that women seem to have felt most at liberty to move from reading to writing' so I will draw some evidence from several family memoirs too. -

Humor, Characterization, Plot: the Role of Secondary Characters in Late Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Marriage Novels

Humor, Characterization, Plot: The Role of Secondary Characters in Late Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Marriage Novels Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Katrina M. Peterson, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Clare Simmons, Adviser Leslie Tannenbaum Jill Galvan ABSTRACT Many late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British novels utilize laughter as a social corrective, but this same laughter hides other messages about women‘s roles. As the genre‘s popularity widened, writers used novels to express opinions that would be eschewed in other, more established and serious genres. My dissertation argues that humor contributes to narrative meaning; as readers laugh at ―minor‖ characters, their laughter discourages specific behaviors, yet it also masks characters‘ important functions within narrative structure. Each chapter examines one type of humor—irony, parody, satire, and wit—along with a secondary female archetype: the matriarch, the old maid, the monster, and the mentor. Traditionally, the importance of laughter has been minimized, and the role of minor characters understudied. My project seeks to redress this imbalance through focusing on humor, secondary characterization, and plot. Chapter One, ―Irony and The Role of the Matriarch,‖ explores the humorous characterizations of Lady Maclaughlan and Miss Jenkyns within Susan Ferrier‘s Marriage (1818) and Elizabeth Gaskell‘s Cranford (1853). These novels share the following remarkable similarities: 1) they use characterization to unify unusually- structured novels; 2) they focus on humorous figures whose contributions to plot are masked by irony; 3) their matriarchal characters are absent for large portions of the stories; and 4) despite their absences, these figures‘ matriarchal power carries strong feminist implications. -

Download This PDF: 24042020 Extant Applications

East Lothian Council LIST OF EXTANT APPLICATIONS RECEIVED SINCE 3RD AUGUST 2009 WITH THE PLANNING AUTHORITY AS OF 24th April 2020 VIEWING THE APPLICATION The application, plans and other documents can be viewed electronically through the Council’s planning portal at www.eastlothian.gov.uk. Section 1 Proposal of Application Notices Section 2 Applications for Planning Permission, Planning Permission in Principle, Approval of Matters Specified in Conditions attached to a Planning Permission in Principle and Applications for such permission made to Scottish Ministers under Section 242A of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 App No.09/00660/LBC Applicant Mr Ronald Jamieson Agent J S Lyell Architectural Services Applicant Address 8 Shillinghill Agents Address Castleview Humbie 21 Croft Street East Lothian Penicuik EH36 5PX EH26 9DH Proposal Replacement of windows and doors (retrospective) - as changes to the scheme of development which is the subject of Listed Building Consent 02/00470/LBC Location 8 Shillinghill Humbie East Lothian EH36 5PX Date by which representations are 30th October 2009 due App No.09/00660/P Applicant Mr Ronald Jamieson Agent J S Lyell Architectural Services Applicant Address 8 Shillinghill Agents Address Castleview Humbie 21 Croft Street East Lothian Penicuik EH36 5PX EH26 9DH Proposal Replacement of windows and doors (retrospective) - as changes to the scheme of development which is the subject of Planning Permission 02/00470/FUL Location 8 Shillinghill Humbie East Lothian EH36 5PX Date by which representations are 27th November 2009 due App No.09/00661/ADV Applicant Scottish Seabird Agent H.Lightoller Centre Applicant Address Per Mr Charles Agents Address Redholm Marshall Greenheads Road The Harbour North Berwick Victoria Road EH39 4RA North Berwick EH39 4SS Proposal Display of advertisements (Retrospective) Location The Scottish Seabird Centre Victoria Road North Berwick East Lothian EH39 4SS Date by which representations are due 13th July 2010 App No.09/00001/SGC Applicant Community Agent Windpower Ltd. -

Making Scenes: Social Theatre and Modes of Survival in Burney’S

MAKING SCENES: SOCIAL THEATRE AND MODES OF SURVIVAL IN BURNEY’S PERFORMATIVE ‘WORLD’ B. SCHAFFNER MA BY RESEARCH THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE OCTOBER 2011 MLA TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements iii Declaration iii Abstract iv INTRODUCTION The Masquerade 01 i Cecilia’s Masquerade 01 ii Burney and the ‘World’ 08 iii The ‘World’ and Its Participants 10 CHAPTER 1 The Rumoured Audience 13 CHAPTER 2 The Authority of Language 28 CHAPTER 3 ‘Private’ Ambition 45 CHAPTER 4 The Death of Performance 61 CHAPTER 5 Heroines Imperiled and Heroes Impotent 76 CONCLUSION 90 WORKS CITED 93 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Sincerest thanks for academic and personal support on this project go to my supervisor Harriet Guest and to Jane Moody. Thanks also to Clare Bond for her perennial competence and generosity, to my fellow CECS students, and to the residents of Constantine House—also known as the best of all possible worlds. DECLARATION All written material and figures, and the ideas therein, are originally conceived and executed by Rebecca E. Schaffner, the author of this dissertation. iii ABSTRACT This study explores the use and representation of social theatrics in Frances Burney’s early works (Evelina, The Witlings, and Cecilia), as a social force, a tool, and a threat stemming from and contributing to an essentially theatrical ‘World.’ Characters are analyzed through two functional pairs of characteristics: the imaginative/nonimaginative and the natural/performative. Chapter 1 discusses gossips as the audience for social performance in Burney’s works. Chapter 2 studies the affective language of two imaginative social performers, Sir Clement Willoughby and Mr.