Life's a Peach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engaging, Enriching, and Inspiring Community

Engaging, Enriching, 2017 - 2018 and Inspiring Community ANNUAL REPORT MISSION Dear Friends, STATEMENT It’s been quite a year for SBIFF – filled with enormous SUCCESS and TRANSFORMATION! Our mission is to engage, enrich, Alongside our many successes has been immense tragedy. The natural and inspire people through the disasters that swept through our community made it some of the most power of film. We celebrate Board of Directors tumultuous times for us. the art of cinema and provide Lynda Weinman During this time, we realized that the 33rd SBIFF was needed more than impactful educational President ever. For each of the 11 days of the Festival, we gathered, reflected, and processed while leaning on one another for strength. This message experiences for our local, Jeffrey Barbakow continues to echo in the feedback we receive – the Festival was a Chairman national and lifeline that unified our fragmented community. We feel very honored to global communities. Linda Armstrong have played this critical role. This experience has crystallized our mission Vice President Treasurer to serve through the power of film. Mimi deGruy As you read this report, you’ll learn about our successes and the impact Vice President Education we make on a year-round basis. Renovating Lynda & Bruce’s Riviera Theatre has been a thrill. Since the grand re-opening on September 13, Susan Eng-Denbaars 2017, we’ve been screening incredible films, including the documentary Vice President Secretary RBG, Academy Award winner Call Me By Your Name, Palme d’Or winner Tammy Hughes The Square, and a 4K restoration of Belle de Jour. -

In Production Preview 8 X 1 Hour Commissioned by &

In production preview LUCA GUADAGNINO’S WE ARE WHO WE ARE 8 x 1 hour Commissioned by & Could be nice to include the Walt Whitman poem that Caitlin reads out to the class, and that is repeated as a refrain throughout the show I am he that aches with amorous love Does the earth gravitate? Does not all matter, aching, attract all matter? A brand new exploration into the So the body of me, to all I meet, “True and Real. complex world of adolescence, friendship and first loves - a story about teenagers, or know Forever and ever” outsiders and embracing difference. I Am He That Aches with Love, Walt Whitman Sometimes, when she kisses me, I feel like she doesn’t know it’s me. She does’t acknowledge me FROM DIRECTOR and she’s kissing a mirror. MAGGIE LUCA GUADAGNINO Call Me By Your Name, I Am Love, Suspiria FRASER: Americans can only be happy in America MAGGIE: This is America STARRING “I’m always looking for stuff that means something” FRASER CHLOE SEVIGNY Queen & Slim, The Act, Kids, Boys “Have you ever really been in love with anyone? Do you know what it feels like?” BRITNEY Don’t Cry, Big Love “It’s exhausting to have to be his mother and father at the same time. To be everything all the JACK DYLAN GRAZER time.” SARAH IT, IT Chapter 2, Me Myself and I, Shazam “I’ve been a lot of things. And I stopped being a lot of things. Truth is sometimes I no longer know JORDAN KRISTINE SEAMON who I am.” JENNY KID CUDI FRASER: “Just because my moms are lesbians doesn’t mean I’m gay.” Westworld, How to Make it in America CAITLIN: “You don’t have to not-be-gay either.” ALICE BRAGA I Am Legend, Queen of the South CAITLIN: “Since you got here everything’s mixed up” FRANCESCA SCORSESE FRASER: “Mixed up good or mixed up bad?” The Departed, The Aviator CAITLIN: “Mixed up full of life” “True and Real. -

Maria Djurkovic Production Designer

MARIA DJURKOVIC PRODUCTION DESIGNER FILM & TELEVISION THE LITTLE DRUMMER GIRL Director: Park Chan-Wook Production Company: AMC Networks & BBC Nominated, Best Production Design, BAFTA Awards (2019) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2018) RED SPARROW Director: Francis Lawrence Production Company: Chernin Entertainment THE SNOWMAN Director: Tomas Alfredson Production Company: Working Title GOLD Director: Stephen Gaghan Production Company: Black Bear Pictures NEW WORLD (Pilot) Director: Gus Van Sant Production Company: HBO A BIGGER SPLASH Director: Luca Guadagnino Production Company: Frenesy Film Official Selection, Venice Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2015) LUX ARTISTS | 1 THE IMITATION GAME Director: Morten Tyldum Production Company: The Weinstein Co. Nominated, Best Production Design, Director & Picture, Academy Awards (2015) Nominated, Best Production Design & Film, BAFTA Awards (2015) Winner, Peoples Choice Award, Toronto Film Festival (2014) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2014) THE INVISIBLE WOMAN Director: Ralph Fiennes Production Company: BBC Films Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2013) TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY Director: Tomas Alfredson Production Company: Working Title & Studio Canal Winner, Best Production Design, British Independent Film Awards (2014) Winner, Best Production Design, London Critics Circle Film Awards (2012) Winner, Best Production Design, European Film Awards (2012) Winner, Best Adapted Screenplay & British Film, BAFTA Awards (2012) Nominated, Best Production -

2017 Producers Book Finalists

PRODUCERS BOOK & PRINT SOURCE LIST Pre-Festival Edition THE 2017 PRODUCERS BOOK A LETTER FROM THE SCREENPLAY & FILM COMPETITION DIRECTORS Hello! Each year, we prepare our annual Producers Book which contains loglines and contact information for the year’s top scripts in our various Script Competitions. Please feel free to reach out to any of the writers listed here to request a copy of their scripts. Also included is our Print Source List containing information for all films selected for the 2017 Festival. This year’s Semifinalists and Finalists were chosen from a field of 9,487 scripts entered in our Screenplay, Digital Series, Playwriting, and Fiction Podcast Competitions. Each year we are amazed by the professional quality and talent that we receive and this year wasn’t any different. The Competition is open to feature-length scripts in the genres of drama, comedy, sci-fi, and horror; teleplay pilots and specs, short scripts, stage plays, fiction podcast scripts, and digital series scripts. Year after year, our strive in programming the Austin Film Festival film slate is to discover and champion the writers and those who can translate amazing stories to the screen. We received over 5,000 film submissions this year and had the task of whittling it down to 182 films that embody our mission and passion for storytelling. It was a harrowing task, but it led to our strongest year of film yet. We’re so proud of this year’s diverse group of filmmakers and unique voices and can’t wait for these works to be seen, shared, and loved. -

Friday 14 February 2020, London. BFI Southbank's TILDA SWINTON

Friday 14 February 2020, London. BFI Southbank’s TILDA SWINTON season, programmed in partnership with the performer and filmmaker herself, will run from 1 – 18 March 2020, celebrating the extraordinary, convention-defying career of one of cinema’s finest and most deft chameleons. The BFI today announce that a number of Swinton’s closest collaborators will join her on stage during the season to speak about their work together including Wes Anderson (Isle of Dogs, The French Dispatch, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Moonrise Kingdom), Bong Joon-ho (Snowpiercer, Okja), Sally Potter (Orlando) and Joanna Hogg (The Souvenir, Caprice). Also announced today is Tilda Swinton’s Film Equipment (28 February – 26 April) a free exhibit to accompany the season which has been curated in close collaboration with BFI and Swinton’s personal archive. Alongside a programme of feature film screenings, shorts and personal favourites, the season will include Tilda Swinton in Conversation with host Mark Kermode on 3 March, during which Swinton will look back on her wide- reaching career as a performer across independent and Hollywood cinema, as well as producer, director and general ally of maverick free spirits everywhere. On the same evening will be Tilda Swinton and Wes Anderson on stage: A Magical Tour of Cinema – a unique chance to hear from two of the most fervent disciples of the church of make believe, as Swinton and Anderson take to the BFI stage to discuss their many collaborations and their film passions. The event will offer a glimpse into their intimate partnership as the two long-time co-conspirators and voracious cinephiles select and explore personal favourite gems from throughout cinema’s history. -

The Importance and Achievements of Luca Guadagnino's Call Me By

To Speak or to Die: The Importance and Achievements of Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name (2017) Treball de Fi de Grau/ BA dissertation Author: Alex Dalmau Barreal Supervisor: Dr. Sara Martín Alegre Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística Grau d‘Estudis Anglesos June 2020 CONTENTS 0. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 0.1 Luca Guadagnino‘s Life and Work ........................................................................ 1 0.2 Guadagnino‘s Call Me by Your Name .................................................................... 2 1. Adapting a Novel: A Work of Respect ......................................................................... 6 1.1 Differences and similarities .................................................................................... 6 1.2 Controversies while Adapting .............................................................................. 12 2. A Film with a Legacy ................................................................................................. 17 2.1 Importance within the LGBT community ............................................................ 17 2.2 Impact within the film industry ............................................................................ 21 3. Conclusions and further research ............................................................................... 27 Works Cited ................................................................................................................... -

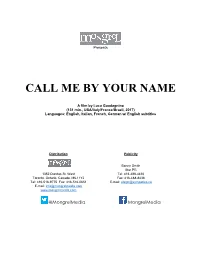

Call Me by Your Name

Presents CALL ME BY YOUR NAME A film by Luca Guadagnino (131 min., USA/Italy/France/Brazil, 2017) Languages: English, Italian, French, German w/ English subtitles Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia CALL ME BY YOUR NAME The Cast Oliver ARMIE HAMMER Elio TIMOTHÉE CHALAMET Mr. Perlman MICHAEL STUHLBARG Annella AMIRA CASAR Marzia ESTHER GARREL Chiara VICTOIRE DU BOIS Mafalda VANDA CAPRIOLO Anchise ANTONIO RIMOLDI Art Historian 1 ELENA BUCCI Art Historian 2 MARCO SGROSSO Mounir ANDRÉ ACIMAN Isaac PETER SPEARS 2 CALL ME BY YOUR NAME The Filmmakers Director LUCA GUADAGNINO Screenplay JAMES IVORY Based on the Novel Call Me By Your Name by ANDRÉ ACIMAN Producers PETER SPEARS LUCA GUADAGNINO EMILIE GEORGES RODRIGO TEIXERA MARCO MORABITO JAMES IVORY HOWARD ROSENMAN Executive Producers DEREK SIMONDS TOM DOLBY MARGARETHE BAILLOU FRANCESCO MELZI D’ERIL NAIMA ABED NICHOLAS KAISER SOPHIE MAS LOURENÇO SANT’ANNA Director of Photography SAYOMBHU MUKDEEPROM Editor WALTER FASANO Production Designer SAMUEL DESHORS Costume Designer GIULIA PIERSANTI Songs “Mystery of Love” and “Visions of Gideon” Written and Performed by SUFJAN STEVENS Production Sound Mixer YVES-MARIE OMNES Re-Recording Mixer JEAN-PIERRE LAFORCE Music Supervisor ROBIN URDANG Music Consultant GERRY GERSHMAN Casting / Line Producer STELLA SAVINO Main Titles -

Luca Guadagnino S New HBO/SKY Drama Series WE ARE

Luca Guadagnino’s new HBO/SKY drama series WE ARE WHO WE ARE debuts September 14 on HBO MIAMI, FL., 27 de julio de 2020 – Academy Award-nominated Luca Guadagnino brings his unique cinematic style to television for the first time with the eight-episode series WE ARE WHO WE ARE, debuting September 14, exclusively on HBO and HBO GO. A story about two American kids who live on a U.S. military base in Italy, the series explores friendship, first-love, identity, and immerses the audience in all the messy exhilaration and anguish of being a teenager – a story which could happen anywhere in the world, but in this case, happens in this little slice of America in Italy. The series was an official selection of the 2020 Cannes Film Festival Directors’ Fortnight. The cast of WE ARE WHO WE ARE includes: Chloë Sevigny, Jack Dylan Grazer, Alice Braga, Jordan Kristine Seamón, Spence Moore II, Kid Cudi, Faith Alabi, Francesca Scorsese, Ben Taylor, Corey Knight, Tom Mercier and Sebastiano Pigazzi. Jack Dylan Grazer stars as shy and introverted fourteen-year-old Fraser, who moves from New York to a military base in Veneto with his mothers, Sarah (Chloë Sevigny) and Maggie (Alice Braga), who are both in the U.S. Army. Tom Mercier (Jonathan) plays Sarah’s assistant. Jordan Kristine Seamón stars as the seemingly bold and confident Caitlin, who has lived with her family on the base for several years and speaks Italian. Compared to her older brother Danny (Spence Moore II), Caitlin has the closer relationship with their father, Richard (Kid Cudi), and does not communicate well with her mother Jenny (Faith Alabi). -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

Music and History in Italian Film Melodrama, 1940-2010

Between Soundtrack and Performance: Music and History in Italian Film Melodrama, 1940-2010 By Marina Romani A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Barbara Spackman, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Linda Williams Professor Mia Fuller Summer 2015 Abstract Between Soundtrack and Performance: Music and History in Italian Film Melodrama, 1940-2010 by Marina Romani Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Barbara Spackman, Chair Melodrama manifests itself in a variety of forms – as a film and theatre practice, as a discursive category, as a mode of imagination. This dissertation discusses film melodrama in its visual, gestural, and aural manifestations. My focus is on the persistence of melodrama and the traces it leaves on post-World War II Italian cinema: from the Neorealist canon of the 1940s to works that engage with the psychological and physical, private, and collective traumas after the experience of a totalitarian regime (Cavani’s Il portiere di notte, 1974), to postmodern Viscontian experiments set in a 21st-century capitalist society (Guadagnino’s Io sono l’amore, 2009). The aural dimension is fundamental as an opening to the epistemology of each film. I pay particular attention to the presence of operatic music – as evoked directly or through semiotic displacement involving the film’s aesthetic and expressive figures – and I acknowledge the existence of a long legacy of practical and imaginative influences, infiltrations and borrowings between the screen and the operatic stage in the Italian cinematographic tradition. -

66Th Miff Announces Full Program

66TH MIFF ANNOUNCES FULL PROGRAM GURRUMUL WORLD PREMIERE AT CLOSING NIGHT JANE CAMPION, MELISSA GEORGE AND LUCA GUADAGNINO LEAD GUEST LINE-UP SALLY POTTER AND PIONEERING WOMEN RETROSPECTIVES UNVEILED MELBOURNE, 12 JULY 2017 – Celebrating its 66th year, the Melbourne International FIlm Festival (MIFF) unleashes its full program with a mammoth line-up of more than 358 films representing 68 countries, including 251 features, 88 shorts, 17 Virtual Reality experiences, 12 MIFF Talks events, 31 world premieres and 135 Australian premieres. It all happens over 18 days, spanning 13 venues across Melbourne, from 3 to 20 August 2017. “What a pleasure it is to launch this year’s Melbourne International Film Festival,” said Artistic Director Michelle Carey. “This year’s program offers audiences an amazing opportunity to explore new worlds through film – from our Pioneering Women and Sally Potter retrospectives to the return of our Virtual Reality program as well as a particularly strong line-up of special events, we can’t wait to open the doors to MIFF 2017.” After kicking-off the festival with the Opening Night Gala screening of Greg McLean’s MIFF Premiere Fund-supported JUNGLE, presented by Grey Goose Vodka, the festival will wind up with the world premiere CLOSING NIGHT screening of Paul Williams’ GURRUMUL. A profound exploration of the life and music of revered Australian artist Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu, the film uses the tools of the artist’s music – chord, melody, song – and the sounds of the land to craft an audio-first cinematic experience, offering a rare insight into a reclusive master. After the film, the audience will enjoy MIFF’s famous Closing Night party at the Festival Lounge. -

Luca Guadagnino, Carice Van Houten and Viktoriya Isakova Join the Guests of the 26Th Geneva International Film Festival

Press release October 28, 2020 Luca Guadagnino, Carice van Houten and Viktoriya Isakova join the guests of the 26th Geneva International Film Festival The GIFF is pleased to announce the arrival of three renowned talents, who will present exclusive series in Geneva from 6 to 15 November. Three big names join the already generous line-up of the 26th edition of the Geneva International Film Festival (GIFF). After Mads Mikkelsen, Woodkid, Abel Ferrara, Sara Forestier and André Dussollier, the event is pleased to announce that Italian filmmaker Luca Guadagnino (Call Me By Your Name, A Bigger Splash, ...), Dutch producer, actress and creator Carice van Houten (The Black Book by Paul Verhoeven, Game of Thrones, ...) and Russian actress Viktoriya Isakova (The Island by Pavel Lungin, The Student by Kirill Serebrennikov, ...) will all be in Geneva to present their latest works and collaborations. Academy Award Nominated director and producer Luca Guadagnino, a rare filmmaker who is one of the great names in contemporary cinema, will personally present the complete HBO-SKY series We Are Who We Are, produced By The Apartment And Wildside, Both Fremantle Companies, with Small Forward, which he directed and co-created, and which the Festival is showing in association with the Director’s Fortnight. On this occasion, Les Cinémas du Grütli will give the public the opportunity to rediscover more widely the work of this fascinating director, capable like no other of bringing out the beauty, the turmoil and the mystery in the course of a shot or a sequence. We Are Who We Are will be available in Switzerland on Starzplay in 2021.