ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myra Hess Had to Wait for Her Ultimate Breakthrough in Her English Homeland; for This Reason, She Initially Had to Earn Her Living by Teaching

Hess, Myra Irene Scharrer. However, Myra Hess had to wait for her ultimate breakthrough in her English homeland; for this reason, she initially had to earn her living by teaching. Her first major success abroad was her debut in Amster- dam, where she performed Schumann's Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra un- der Willem Mengelberg in 1912. In 1922 followed her de- but in New York, where she was celebrated with equal en- thusiasm. Her career advanced rapidly from that point onwards, and she rose to the position of one of the most successful pianists in her homeland during the ensuing years. During the 1930s, she undertook extended concert tours throughout all of Europe, including the Scandinavi- an countries, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Tur- key, Yugoslavia, Germany, France and Holland. At the be- ginning of the Second World War, when all of London's concert halls were closed, she founded the legendary "Lunchtime Recitals" at the National Gallery, offering the London public a broad spectrum of high-quality pro- grammes with both young and established musicians. She herself performed at the National Gallery 146 times. The concerts were held without interruption until 10 Ap- Die Pianistin Myra Hess ril 1946. In 1941 Myra Hess was honoured with the title "Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire" Myra Hess for her special efforts on behalf of musical life in her ho- meland. After the Second World War, the meanwhile fa- * 25 February 1890 in Hampstead (im heutigen mous pianist regularly gave concerts in her native count- Londoner Stadtbezirk Camden), England ry and in the USA, where she enjoyed great popularity. -

MAHANI TEAVE Concert Pianist Educator Environmental Activist

MAHANI TEAVE concert pianist educator environmental activist ABOUT MAHANI Award-winning pianist and humanitarian Mahani Teave is a pioneering artist who bridges the creative world with education and environmental activism. The only professional classical musician on her native Easter Island, she is an important cultural ambassador to this legendary, cloistered area of Chile. Her debut album, Rapa Nui Odyssey, launched as number one on the Classical Billboard charts and received raves from critics, including BBC Music Magazine, which noted her “natural pianism” and “magnificent artistry.” Believing in the profound, healing power of music, she has performed globally, from the stages of the world’s foremost concert halls on six continents, to hospitals, schools, jails, and low-income areas. Twice distinguished as one of the 100 Women Leaders of Chile, she has performed for its five past presidents and in its Embassy, along with those in Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, China, Japan, Ecuador, Korea, Mexico, and symbolic places including Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Chile’s Palacio de La Moneda, and Chilean Congress. Her passion for classical music, her local culture, and her Island’s environment, along with an intense commitment to high-quality music education for children, inspired Mahani to set aside her burgeoning career at the age of 30 and return to her Island to found the non-profit organization Toki Rapa Nui with Enrique Icka, creating the first School of Music and the Arts of Easter Island. A self-sustaining ecological wonder, the school offers both classical and traditional Polynesian lessons in various instruments to over 100 children. Toki Rapa Nui offers not only musical, but cultural, social and ecological support for its students and the area. -

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis

MAHLER 9 16, 17 & 19 MARCH 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Aspiring to the sublime: Mahler 9 And in ceasing, we lose it all. But in letting go, we have gained everything.’ ‘Wohin ich geh'? Ich geh', ich wand're in die Berge. Ich suche Ruhe für mein einsam Herz.’ Almost at the end of MSO’s Mahler cycle (Where do I go? I go, I wander in the of Symphonies, the Ninth aspires to the mountains. I seek peace for my lonely heart.) sublime, and to what lies beyond. Mahler’s Ninth Symphony continues where Ronald Vermeulen Der Abschied, the last movement from his Director of Artistic Planning Lied von der Erde, ends. A similar feeling of farewell and resignation permeates most of this Symphony. Is it a coincidence that the first movement opens with a motif that For further listening we recommend: alludes to Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No.26 On 7–8 June, conductor Andrea Molino Les Adieux? Beethoven wrote the word will lead the MSO in a Mahler rarity: the ‘Le-be-wohl’ (Farewell) above the three tone poem Totenfeier. This work became Melbourne Symphony Orchestra descending chords that Mahler quotes the basis for the first movement of in his Symphony. Mahler’s Second Symphony. But even after Sir Andrew Davis conductor The two middle movements are an the Symphony’s premiere, Mahler kept emotional rollercoaster, with an angelic performing Totenfeier as a separate piece. trumpet melody in the Rondo Burlesque In the same concert, Mahler-baritone par pointing at the sublime serenity of the excellence, Thomas Hampson will perform Mahler Symphony No.9 Adagio that concludes the Symphony. -

The Blake Collection in Memory of Nancy M

The Blake Collection In Memory of Nancy M. Blake BELLINI’S NORMA featuring CECILIA BARTOLI This tragic opera is set in Roman-occupied, first-century Gaul, features a title character, who although a Druid priestess, is in many ways a modern woman. Norma has secretly taken the Roman proconsul Pollione as her lover and had two children with him. Political and personal crises arise when the locals turn against the occupiers and Pollione turns to a new paramour. Norma “is a role with emotions ranging from haughty and demanding, to desperately passionate, to vengeful and defiant. And the singer must convey all of this while confronting some of the most vocally challenging music ever composed. And if that weren't intimidating enough for any singer, Norma and its composer have become almost synonymous with the specific and notoriously torturous style of opera known as bel canto — literally, ‘beautiful singing’” (“Love Among the Druids: Bellini's Norma,” NPR World of Opera, May 16, 2008). And Bartoli, one of the greatest living opera divas, is up to the challenges the role brings. (New York Public Radio’s WQXR’s “OperaVore” declared that “Bartoli is Fierce and Mercurial in Bellini's Norma,” Marion Lignana Rosenberg, June 09, 2013.) If you’re already a fan of this opera, you’ve no doubt heard a recording spotlighting the great soprano Maria Callas (and we have such a recording, too), but as the notes with the Bartoli recording point out, “The role of Norma was written for Giuditta Pasta, who sang what today’s listeners would consider to be mezzo-soprano roles,” making Bartoli more appropriate than Callas as Norma. -

Metamorphosis a Pedagocial Phenomenology of Music, Ethics and Philosophy

METAMORPHOSIS A PEDAGOCIAL PHENOMENOLOGY OF MUSIC, ETHICS AND PHILOSOPHY by Catalin Ursu Masters in Music Composition, Conducting and Music Education, Bucharest Conservatory of Music, Romania, 1983 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Faculty of Education © Catalin Ursu 2009 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall, 2009 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

ARSC Journal

THE ART OF DINU LIPATTI - and a cautionary tale THE ART OF DINU LIPATTI. RECORD 1: BACH Partita No. 1 in B flat, BWV 825; Chorale Preludes: Nun Komm', der Heiden Reiland, BWV 599, Ich ruf' zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 639 (arr. Busoni); Jesu, joy of man's desiring (Cantata 147) (arr. Hess); Siciliana (Flute Sonata No. 2) (arr. Kempff) MOZART Piano Sonata No. 8 in A minor, K 310 RECORD 2: SCARLATTI Sonatas in E, KK 380, and D minor, KK 9 CHOPIN Barcorolle in F sharp, Op. 60 LISZT Sonetto del Petrarca No. 104 RAVEL Alborada del Gracioso ('Miroirs' No. 4) CHOPIN Piano Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58 RECORD 3: CHOPIN Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 (with Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra conducted by Otto Ackermann); Etudes in E minor, Op. 25 No. 5 and Op. 10 No. 5; Nocturne No. 8 in D flat, Op. 27 No. 2; Mazurka in C sharp minor, Op. 50 No. 3; Waltz in A flat, Op. 34 No. 1 RECORD 4: MOZART Piano Concerto No. 21 in C, K 467 (with Lucerne Festival Orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan) ENESCO Piano Sonata No. 3 in D, Op.24. (recorded 1943-1950) Not a note of Lipatti is unconsidered, nor yet is there one which does not sound utterly spontaneous and beautiful; not a phrase does not lift itself in a life-enhancing way yet remain precisely calculated in re lation to the next and to the whole. But, alas, almost every comment to be made about these, for the most part, well-known recordings must by now be a cliche. -

DINU LIPATTI • the Last Recital 8.111366 Time 78:39 Playing Waltz in a Flat, Op

8.111366 rr Lipatti_EU:8.111366 rr Lipatti_EU 17-12-2010 18:13 Pagina 1 NAXOS Historical NAXOS Historical NAXOS 8.111366 DINU LIPATTI Playing Time ADD The Last Recital 78:39 ൿ of this compact disc prohibited. and copying broadcasting Unauthorised public performance, texts and translations reserved. artwork, All rights in this sound recording, Besançon, 16th September 1950 & Ꭿ 1 Applause and arpeggios 0:33 It is not surprising that Lipatti achieved cult 2011 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Made in Germany 2011 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Johann Sebastian BACH: Partita No. 1 in B flat minor, BWV 825 17:20 2 Praeludium 1:51 status in the years following his death at the 3 Allemande 2:33 4 Courante 2:52 age of 33. He was an extremely sensitive 5 Sarabande 4:41 musician and a man whose approach to the 6 Menuet 1; Menuet 2 2:51 DINU LIPATTI • The Last Recital 7 Gigue 2:32 piano was one of utter fastidiousness, DINU LIPATTI • The Last Recital 8 Applause and arpeggios 0:26 Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART: Sonata No. 8 in A minor, K. 310 14:10 always striving for perfection in every 9 Allegro maestoso 5:20 0 Andante cantabile 5:56 aspect of his interpretation and ! Presto 2:54 performance. Throughout this Besançon Franz SCHUBERT: Impromptus, Op. 90, D. 899 @ No. 3 in G flat major 5:06 recital there is a clarity of sound, evenness # No. 2 in E flat major 4:10 Fryderyk CHOPIN: Waltzes of attack and scrupulous attention to $ No. 5 in A flat major, Op. -

Liszt and Russia" TABLE of CONTENTS by Dmitry Rachmanov, Host

Founded in 1964 Volume 31, Number 2 An officiAl publicAtion of the AmericAn liszt society, inc. 2016 Festival: "Liszt and Russia" TABLE OF CONTENTS by Dmitry Rachmanov, host The theme of the American Liszt Society’s 2016 festival and conference is “Liszt and Russia.” The festival is being presented by the Department of Music at California State 1 "Liszt and Russia" University, Northridge, June 2 - 5. 2016 ALS Festival/Conference, The genesis of the festival theme goes back to Liszt’s tours of Russia in the 1840s by Dmitry Rachmanov and his contacts with Russian musicians. Liszt’s influence and support of music and musicians in Russia lasted throughout his mature life. This opens a fertile ground of 2 President's Message exploration of Franz Liszt’s legacy and lasting mark on Russian musical culture and musicians. Liszt’s impact on Russian music history and its development is hard to overestimate; during his heyday as the world's preeminent piano virtuoso, he made 3 Letter from the Editor three tours of Russia (1842 - 1847), leaving an indelible and powerful impression in all circles of Russian society. Subsequently, many Russian musicians made their pilgrimage to visit Liszt in Weimar and other places where he resided. On his part, 4 2016 ALS Festival Schedule Liszt encouraged and supported many Russian composers by performing their music, making piano transcriptions of their works, and popularizing them in other ways. The festival will feature eclectic and stimulating programming. Special events 5 A Conversation with include solo recitals by the most recent Van Cliburn Gold Medalist, Vadym Dmitry Rachmanov Kholodenko, with works by Liszt and Scriabin; the Italian pianist Antonio Pompa- Baldi, one of ALS's regular featured artists, performing works by Liszt and Anton Rubinstein; and a senior professor of the Moscow Conservatory, Mikhail Voskresensky, 8 In Memoriam: Maurice Hinson, presenting music by Liszt, Borodin, Glinka-Balakirev, Tchaikovsky, Medtner, and by Wesley Roberts Prokofiev. -

A Summer of Concerts Live on WFMT

A summer of concerts live on WFMT Thomas Wilkins conducts the Grant Park Music Festival from the South Shore Cultural Center Friday, July 29, 6:30 pm Air Check Dear Member, The Guide Greetings! Summer in Chicago is a time to get out and about, and both WTTW and WFMT are out in The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT the community during these warmer months. We’re bringing PBS Kids walk-around character Nature Renée Crown Public Media Center Cat outdoors to engage with kids around the city and suburbs, encouraging them to discover the 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue natural world in their own back yards; and we recently launched a new Chicago Loop app, which you Chicago, Illinois 60625 can download to join Geoffrey Baer and explore our great city and its architectural wonders like never Main Switchboard before. And on musical front, WFMT is proud to bring you live summer (773) 583-5000 concerts from the Ravinia and Grant Park festivals; this month, in a first Member and Viewer Services for the station, we will be bringing you a special Grant Park concert from (773) 509-1111 x 6 the South Shore Cultural Center with the Grant Park Orchestra led by WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 guest conductor Thomas Wilkins. Remember that you can take all of this Chicago Production Center content with you on your phone. Go to iTunes to download the WTTW/ (773) 583-5000 PBS Video app, the new WTTW Chicago’s Loop app, and the WFMT app for Apple and Android. -

Dinu Lipatti Concerto in a Minor Op. 54 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dinu Lipatti Concerto In A Minor Op. 54 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Concerto In A Minor Op. 54 Country: Netherlands Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1123 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1494 mb WMA version RAR size: 1224 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 243 Other Formats: AIFF AUD DTS ASF RA MIDI APE Tracklist Concerto In A Minor (Schumann - Op. 54) A First Movement -- Allegro Affettuoso (First Part) B First Movement -- Allegro Affettuoso (Second Part) C First Movement -- Allegro Affettuoso (Third Part) D First Movement -- Allegro Affettuoso - Cadenza - Allegro Molto (Conclusion) E Second Movement -- Intermezzo. Andantino Grazioso F Third Movement -- Allegro Vivace (First Part) G Third Movement -- Allegro Vivace (Second Part) H Third Movement -- Allegro Vivace (Conclusion) Credits Composed By – Schumann* Conductor – Herbert von Karajan Orchestra – The Philharmonia Orchestra* Piano – Dinu Lipatti Notes Recorded 9 & 10 April 1948 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Schumann* - Dinu Schumann* - Dinu Lipatti And The Lipatti And The Philharmonia Philharmonia 33C1001, Orchestra* Conducted Columbia, 33C1001, Orchestra* UK Unknown 33 C 1001 By Herbert von Columbia 33 C 1001 Conducted By Karajan - Pianoforte Herbert von Concerto In A Minor Karajan (10") Schumann* - Pian : Dinu Lipatti / Schumann* - Pian : Orchestra Dinu Lipatti / "Philharmonia" - Orchestra ECD 67, Londra* ● Dirijor : Electrecord, ECD 67, "Philharmonia" - Romania 1958 ECD - 67 Herbert von Karajan - Electrecord ECD - -

1. 101 Strings: Panoramic Majesty of Ferde Grofe's Grand

1. 101 Strings: Panoramic Majesty Of Ferde Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite 2. 60 Years of “Music America Loves Best” (2) 3. Aaron Rosand, Rolf Reinhardt; Southwest German Radio Orchestra: Berlioz/Chausson/Ravel/Saint-Saens 4. ABC: How To Be A Zillionaire! 5. ABC Classics: The First Release Seon Series 6. Ahmad Jamal: One 7. Alban Berg Quartett: Berg String Quartets/Lyric Suite 8. Albert Schweitzer: Mendelssohn Organ Sonata No. 4 In B-Flat Major/Widor Organ Symphony No. 6 In G Minor 9. Alexander Schneider: Brahms Piano Quartets Complete (2) 10. Alexandre Lagoya & Claude Bolling: Concerto For Classic Guitar & Jazz Piano 11. Alexis Weissenberg, Georges Pretre; Chicago Symphony Orchestra: Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 3 12. Alexis Weissenberg, Herbert Von Karajan; Orchestre De Paris: Tchaikovsky Concerto #2 13. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Gregorian Chant-Easter Processions 14. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Music At Notre Dame 1200-1375 Guillaume De Machaut 15. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Songs From Taverns & Chapels 16. Alfred Deller; Deller Consort: Te Deum/Jubilate Deo 17. Alfred Newman; Brass Of The Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra: Hallelujah! 18. Alicia De Larrocha: Grieg/Mendelssohn 19. Andre Cluytens; Paris Conservatoire Orchestra: Bizet 20. Andre Kostelanetz & His Orchestra: Columbia Album Of Richard Rodgers (2) 21. Andre Kostelanetz & His Orchestra: Verdi-La Traviata 22. Andre Previn; London Symphony Orchestra: Rachmaninov/Shostakovich 23. Andres Segovia: Plays J.S. Bach//Edith Weiss-Mann Harpsichord Bach 24. Andy Williams: Academy Award Winning Call Me Irresponsible 25. Andy Williams: Columbia Records Catalog, Vol. 1 26. Andy Williams: The Shadow Of Your Smile 27. Angel Romero, Andre Previn: London Sympony Orchestra: Rodrigo-Concierto De Aranjuez 28. -

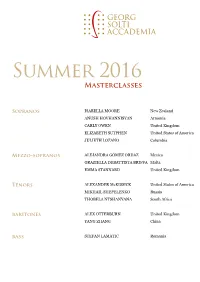

Summer 2016 Masterclasses

Summer 2016 Masterclasses Sopranos ISABELLA MOORE New Zealand ANUSH HOVHANNISYAN Armenia CARLY OWEN United Kingdom ELIZABETH SUTPHEN United States of America JULIETH LOZANO Columbia Mezzo-sopranos ALEJANDRA GÓMEZ ORDAZ Mexico GRAZIELLA DEBATTISTA BRIFFA Malta EMMA STANNARD United Kingdom Tenors ALEXANDER McKISSICK United States of America MIKHAIL SHEPELENKO Russia THOBELA NTSHANYANA South Africa baritones ALEX OTTERBURN United Kingdom YANG ZHANG China bass STEFAN LAMATIC Romania SOPRANO Isabella Moore is a soprano from Auckland, New Zealand. In 2014 she completed a Master’s degree in Advanced Vocal Studies with Distinction at the Wales International Academy of Voice, under the tutelage of Dennis O’Neill and Nuccia Focile. Prior to that, she gained a Bachelor of Music degree and a Postgraduate Diploma in Voice Perfor- mance from the New Zealand School of Music at Victoria University. Isabella’s opera work includes the lead role of Gulnara in Verdi’s II corsaro. She has ISABELLA taken part in masterclasses with artists such as Dame Kiri Te Kanawa and Montserrat MOORE Caballé. Her most recent achievements include: winning the 2015 Joan Sutherland and New Zealand | 25 Richard Bonynge Bel Canto Award in Sydney; second place in the 2015 Sydney Eistedd- fod McDonald’s Operatic Aria; winning the 2015 Sydney Eisteddfod Joan Sutherland Memorial Senior Vocal Scholarship; winning the 2014 New Zealand Aria Competition in Rotorua (NZ); winning the 2014 IFAC Australian Singing Competition (The ‘Mathy’) in Sydney and winning the prestigious 2014 New Zealand Lexus Song Quest Competi- tion in Auckland (NZ). Isabella was a finalist in the 2014 ROSL Music Competition in London where she received an International Competitor’s Award.