Quebec and the Charter of Values Sherry Simon In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

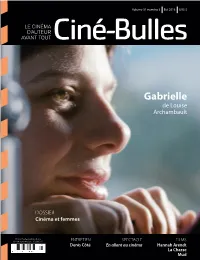

Gabrielle De Louise Archambault

Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 5,95 $ ÉTÉ 2013 Gabrielle de Louise Archambault DOSSIER Cinéma et femmes REVUE DE CINÉMA PUBLIÉE PAR L’ASSOCIATION DES CINÉMAS PARALLÈLES DU QUÉBEC VOLUME 31 NUMÉRO 3 VOLUME DU QUÉBEC PARALLÈLES DES CINÉMAS L’ASSOCIATION PUBLIÉE PAR REVUE DE CINÉMA Envoi Poste-publications No de convention : 40069242 ENTRETIEN SPECTACLE FILMS Denis Côté En allant au cinéma Hannah Arendt La Chasse Mud C0 M49 Y66 K0 Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 2 EN COUVERTURE Gabrielle 2 Entretien avec Louise Archambault SOMMAIRE 8 Commentaire critique ENTRETIEN 12 Denis Côté Scénariste et réalisateur de Vic et Flo ont vu un ours 20 Commentaire critique SPECTACLE 12 59 56 En allant au cinéma FILMS 10 Hannah Arendt de Margarethe von Trotta 58 Au-delà des collines de Cristian Mungiu 59 La Chasse de Thomas Vinterberg 60 The Great Gatsby de Baz Luhrmann 61 Mud de Je Nichols 62 Sarah préfère la course de Chloé Robichaud 10 63 This Must Be the Place de Paolo Sorrentino 23 Introduction au dossier 24 Les pionnières québécoises 28 Au Québec en 2013 38 L’horreur au féminin 42 Le combat émancipateur 46 Du masculin au féminin 50 Les lms les plus populaires 54 Coret 20 Courts et grand talent Volume 31 numéro 3 Été 2013 RÉDACTION ÉDITION ABONNEMENT ANNUEL PAYABLE À L’ACPQ (4 NUMÉROS) Éric Perron, rédacteur en chef Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec (ACPQ) Individuel : 23 $ – Institutionnel : 45,99 $ (taxes comprises) [email protected] Martine Mauroy, directrice générale Étranger : 60 $ (non taxable) 514.252.3021 poste 3413 4545, av. -

Speech by Carolle Brabant, Quebec MBA

QUEBEC MBA ASSOCIATION APRIL 25, 2012 The Canadian audiovisual industry: We mean business Speech delivered by Carolle Brabant, C.P.A., C.A., MBA Executive Director, Telefilm Canada I’d like to thank you for being here today as well as thank the Quebec MBA Association for making culture a part of these lunch-time talks. As an MBA graduate myself, I’m delighted to be able to use this forum to speak to you about a passionate and important industry for the economic and cultural future of Canada: the audiovisual industry. I decided to join this industry over 21 years ago and I’ve never regretted it. It has let me combine my passion for business with my passion for the arts. Every day, I get to work with inspirational, dynamic people who motivate me. 1/24 There’s been much talk of culture in the media these past few weeks as a result of the federal government’s recent budget cuts. But there’s also been much talk about the success garnered by Canadian productions. One need only think of the tremendous box office success enjoyed by Starbuck. It was announced this week that DreamWorks has acquired the remake rights and that Ken Scott would be the director. Then, of course, there’s Monsieur Lazhar, which made it all the way to the Oscars! The Canadian audiovisual industry is a vibrant, active industry that touches us every day through our television screens, at the movies, and increasingly on our computers and phones. It is an industry deserving of our attention, notably because of its contribution to the culture and economy of our country. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

2017 New York

CANADA NOW BEST NEW FILMS FROM CANADA 2017 APRIL 6 – 9 AT THE IFC CENTER, NEW YORK From the recent numerous international successes of Canadian directors such as Xavier Dolan (Mommy, It’s Only the End of the World), Denis Villeneuve (Arrival, and the forthcoming Blade Runner sequel), Philippe Falardeau (The Bleeder, The Good Lie) and Jean-Marc Vallée (Dallas Buyers Club, Wild, Demolition), you might be thinking that there must be something special in that clean, cool drinking water north of the 49th parallel. As this year’s selection of impressive new Canadian films reveals, you would not be wrong. With works from new talents as well as from Canada’s accomplished veteran directors, this series will transport you from the Arctic Circle to western Asia, from downtown Montreal to small town Nova Scotia. And yes, there will be hockey. Get ready to travel across the daring and dramatic contemporary Canadian cinematic landscape. Have a look at what’s now and what’s next in those cinematic lights in the northern North American skies. Thursday, April 6, 7:00PM RUMBLE: THE INDIANS WHO ROCKED THE WORLD CANADA 2017 | 97 MINUTES DIRECTOR: CATHERINE BAINBRIDGE, CO-DIRECTOR: ALFONSO MAIORANA Artfully weaving North American musicology and the devastating historical experiences of Native Americans, Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked The World reveals the deep connections between Native American and African American peoples and their musical forms. A Sundance 2017 sensation, Bainbridge’s and co-director Maiorana’s documentary charts the rhythms and notes we now know as rock, blues, and jazz, and unveils their surprising origins in Native American culture. -

ZOOM- Press Kit.Docx

PRESENTS ZOOM PRODUCTION NOTES A film by Pedro Morelli Starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley Theatrical Release Date: September 2, 2016 Run Time: 96 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Official Website: www.zoomthefilm.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: @screenmediafilm Instagram: @screenmediafilms Theater List: http://screenmediafilms.net/productions/details/1782/Zoom Trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=M80fAF0IU3o Publicity Contact: Prodigy PR, 310-857-2020 Alex Klenert, [email protected] Rob Fleming, [email protected] Screen Media Films, Elevation Pictures, Paris Filmes,and WTFilms present a Rhombus Media and O2 Filmes production, directed by Pedro Morelli and starring Gael García Bernal, Alison Pill, Mariana Ximenes, Don McKellar, Tyler Labine, Jennifer Irwin and Jason Priestley in the feature film ZOOM. ZOOM is a fast-paced, pop-art inspired, multi-plot contemporary comedy. The film consists of three seemingly separate but ultimately interlinked storylines about a comic book artist, a novelist, and a film director. Each character lives in a separate world but authors a story about the life of another. The comic book artist, Emma, works by day at an artificial love doll factory, and is hoping to undergo a secret cosmetic procedure. Emma’s comic tells the story of Edward, a cocky film director with a debilitating secret about his anatomy. The director, Edward, creates a film that features Michelle, an aspiring novelist who escapes to Brazil and abandons her former life as a model. Michelle, pens a novel that tells the tale of Emma, who works at an artificial love doll factory… And so it goes.. -

Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research

University of Alberta The Performance of Identity in Wajdi Mouawad’s Incendies by Nicole Renault A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Drama ©Nicole Renault Fall 2009 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54187-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-54187-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special Programs 215 345 6789

County Theater 79 PreviewsMARCH – MAY 2012 DAMSELS IN DISTRESS DAMSELS INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTY T HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. How can you support ADMISSION COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER General ..............................................................$9.75 Be a member. Members ...........................................................$5.00 Become a member of the nonprofit County Theater and Seniors (62+) show your support for good Students (w/ID) & Children (<18). ..................$7.25 films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a member- Matinees ship form or join on-line. Your financial support is tax-deductible. Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 Make a gift. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .......................................$7.25 Your additional gifts and support make us even better. Your Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ..........................$5.00 donations are fully tax-deductible. And you can even put your Affiliated Theaters Members* .............................$6.00 name on a bronze star in the sidewalk! You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. Contact our Business Office at (215) 348-1878 x117 or at The above ticket prices are subject to change. [email protected]. Be a sponsor. *Affiliated Theaters Members Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange The County Theater, the Ambler Theater, and the Bryn Mawr Film for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety Institute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your membership will of ways – on our movie screens, in our brochures, and on our allow you $6.00 admission at the other theaters. -

Press Kit Directed by Written and Uawad Wajdi Mou

Press Kit written and directed by Wajdi Mouawad 5 — 30 December 2018 Contact details Dorothée Duplan, Flore Guiraud, Camille Pierrepont assisted by Louise Dubreil 01 48 06 52 27 | [email protected] Downloadable Press kit and photos: www.colline.fr > professionnels > bureau de presse 2 Tous des oiseaux 5 – 30 December 2018 at La Colline – théâtre national Show in German, English, Arabic, and Hebrew surtitled in French duration: 4h interval included Cast and Creative Text and stage direction Wajdi Mouawad with Jalal Altawil Wazzan Jérémie Galiana or Daniel Séjourné Eitan Victor de Oliveira the waiter, the Rabbi, the doctor Leora Rivlin Leah Judith Rosmair or Helene Grass Norah Darya Sheizaf Eden, the nurse Rafael Tabor Etgar Raphael Weinstock David Souheila Yacoub or Nelly Lawson Wahida Assistant director Valérie Nègre Dramaturgy Charlotte Farcet Artistic collaboration François Ismert Historical advisor Natalie Zemon Davis Original music Eleni Karaindrou Set design Emmanuel Clolus Lighting design Éric Champoux Sound design Michel Maurer Costume design Emmanuelle Thomas assisted by Isabelle Flosi Make-up and hair design Cécile Kretschmar Hebrew translation Eli Bijaoui English translation Linda Gaboriau English translation Uli Menke Arabic translation Jalal Altawil 2018 Production La Colline – théâtre national The show was created on Novembre 17th in the Main venue at La Colline and has received the Great Prize 2018 of the Professional Review Association. The text has been published by Léméac/Actes Sud-Papiers in January 2018. 3 On tour -

MY INTERNSHIP in CANADA (Guibord S’En Va-T-En Guerre)

MY INTERNSHIP IN CANADA (Guibord s’en va-t-en guerre) Press Kit A political satire by Philippe Falardeau with Patrick Huard Irdens Exantus Clémence Dufresne-Deslières and Suzanne Clément INTERNATIONAL SALES CANADIAN DISTRIBUTION PUBLICITY Sébastien Beffa Sébastien Létourneau Judith Dubeau Films Distribution Les Films Christal IXION Communications +33 1 53 10 33 99 Tél : +1 514 336 9696 +1 514 495 8176 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] My Internship in Canada synopsis Guibord is an independent Member of Parliament who represents Prescott-Makadewà- Rapides-aux Outardes, a vast county in Northern Quebec. As the entire country watches, Guibord unwillingly finds himself in the awkward position of holding the decisive vote to determine whether Canada will go to war. Accompanied by his wife, his daughter and an idealistic intern from Haiti named Souverain (Sovereign) Pascal, Guibord travels across his district in order to consult his constituents. While groups of lobbyists get involved in a debate that spins out of control, the MP will have to face his own conscience. My Internship in Canada (Guibord s’en va-t-en guerre) is a biting political satire in which politicians, citizens and lobbyists go head-to-head tearing democracy to shreds. My Internship in Canada | September 2015 1 My Internship in Canada cast Steve Guibord Patrick HUARD Suzanne Suzanne CLÉMENT Souverain (Sovereign) Pascal Irdens EXANTUS Lune Clémence DUFRESNE-DESLIÈRES Stéphanie Caron-Lavallée Sonia CORDEAU Prime Minister -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

YANA MEERZON This Essay Examines the Forms of History and Memory Representation in Incendies, the 2004 Play by Wajdi Mouawad, An

YANA MEERZON STAGING MEMORY IN WAJDI MOUAWAD ’S INCENDIES : ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE OR POETIC VENUE ? This essay examines the forms of history and memory representation in Incendies , the 2004 play by Wajdi Mouawad, and its 2010 film version, directed by Denis Villeneuve. Incendies tells the story of a twin brother and sister on the quest to uncover the mystery of their mother’s past and the silence of her last years. A contemporary re-telling of the Oedipus myth, the play examines what kind of cultural, collective, and individual memo - ries inform the journeys of its characters, who are exilic children. The play serves Mouawad as a public platform to stage the testimony of his child - hood trauma: the trauma of war, the trauma of exilic adaptation, and the challenges of return. As this essay argues, when moved from one medium to another, Mouawad’s work forces the directors to seek its historical and geographical contextualization. If in its original staging, Incendies allows Mouawad to elevate the story of his personal suffering to the universals of abandoned childhood, to reach in its language the realms of poetic expres - sion, and to make memory a separate, almost tangible entity on stage, then the 2010 film version by Villeneuve turns this play into an archaeological site to excavate the recent history of a single war-torn Middle East country (supposedly Lebanon), an objective at odds with Mouawad’s own view of theatre as a venue where poetry meets politics. Naturally the transposition from a play to a film presupposes a significant mutation of the original and raises questions of textual fidelity. -

Wajdi Mouawad

Wajdi Mouawad Born in 1968, author, actor, and director Wajdi Mouawad spends his early childhood in Lebanon, his adolescence in France, and his young adult years in Quebec before settling in France, where he now lives. He studied in Montreal at École nationale de théâtre du Canada, and is awarded a diploma in performance in 1991. Upon graduation he begins codirecting his first company, Théâtre Ô Parleur, with actor Isabelle Leblanc. In 2005, he establishes two companies, Abé Carré Cé Carré, in Quebec, with Emmanuel Schwarts, and Au Carré de l’Hypoténuse in France. During this time, in 2000, he assumes the role of artistic director for the Théâtre de Quat’Sous in Montreal, a position he will hold for four seasons. He and his French company, Au Carré de l’Hypoténuse were associate artists at l'Espace Malraux, scène nationale de Chambéry et de la Savoie, from 2008 to 2010. In 2009 he is artist in residence of the 63rd edition of the Festival d’Avignon, where he stages the quartet Le Sang des Promesses. He serves as artistic director for the Théâtre français du Centre national des Arts d’Ottawa from 2007 to 2012. Since September 2011, he has been associated artist at the Grand T- Nantes. In April 2016, he is nominated to assume the role of director for the National Theater in Paris, La Colline. His career as stage director began with the Théâtre Ô Parleur, as he contributed his own works to be performed: Partie de cache-cache entre deux Tchécoslovaques au début du siècle (1991), Journée de noces chez les Cromagnons (1994) et Willy Protagoras enfermé dans les toilettes (1998), puis Ce n’est pas la manière qu’on se l’imagine que Claude et Jacqueline se sont rencontrés coécrit avec Estelle Clareton (2000).