Britain and Europe: Where America’S Interests Really Lie Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tory Modernisation 2.0 Tory Modernisation

Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg Guy and Shorthouse Ryan by Edited TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 MODERNISATION TORY edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 THE FUTURE OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 The future of the Conservative Party Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a re- trieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Bright Blue is an independent, not-for-profit organisation which cam- paigns for the Conservative Party to implement liberal and progressive policies that draw on Conservative traditions of community, entre- preneurialism, responsibility, liberty and fairness. First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Bright Blue Campaign www.brightblue.org.uk ISBN: 978-1-911128-00-7 Copyright © Bright Blue Campaign, 2013 Printed and bound by DG3 Designed by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Contents Acknowledgements 1 Foreword 2 Rt Hon Francis Maude MP Introduction 5 Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg 1 Last chance saloon 12 The history and future of Tory modernisation Matthew d’Ancona 2 Beyond bare-earth Conservatism 25 The future of the British economy Rt Hon David Willetts MP 3 What’s wrong with the Tory party? 36 And why hasn’t -

Issues for the United States

The United Kingdom: Issues for the United States Derek E. Mix Analyst in European Affairs May 14, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33105 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The United Kingdom: Issues for the United States Summary Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress view the United Kingdom (UK) as the United States’ closest and most reliable ally. This perception stems from a combination of factors, including a sense of shared history, values, and culture; extensive and long-established bilateral cooperation on a wide range of foreign policy and security issues; and the UK’s strong role in Iraq and Afghanistan. The United States and the UK also cooperate closely on counterterrorism efforts. The two countries share an extensive and mutually beneficial trade and economic relationship, and each is the other’s largest foreign investor. The term “special relationship” is often used to describe the deep level of U.S.-UK cooperation on diplomatic and political issues, as well as on security and defense matters such as intelligence- sharing and nuclear weapons. British officials enjoy a unique level of access to U.S. decision- makers, and British input is often cited as an element in shaping U.S. foreign policy debates. Few question that the two countries will remain close allies that choose to cooperate on many important global issues such as counterterrorism, the NATO mission in Afghanistan, and efforts to curb Iran’s nuclear activities. At the same time, some observers have called for a reassessment of the “special relationship” concept. -

National Theatre

WITH EMMA BEATTIE OLIVER BOOT CRYSTAL CONDIE EMMA-JANE GOODWIN JULIE HALE JOSHUA JENKINS BRUCE MCGREGOR DAVID MICHAELS DEBRA MICHAELS SAM NEWTON AMANDA POSENER JOE RISING KIERAN GARLAND MATT WILMAN DANIELLE YOUNG 11 JAN – 25 FEB 2018 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE Presented by Melbourne Theatre Company and Arts Centre Melbourne This production runs for approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes, including a 20 minute interval. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is presented with kind permission of Warner Bros. Entertainment. World premiere: The National Theatre’s Cottesloe Theatre, 2 August 2012; at the Apollo Theatre from 1 March 2013; at the Gielgud Theatre from 24 June 2014; UK tour from 21 January 2017; international tour from 20 September 2017 Melbourne Theatre Company and Arts Centre Melbourne acknowledge the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the Traditional Owners of the land on which this performance takes place, and we pay our respects to Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors past and present, and to our shared future. DIRECTOR MARIANNE ELLIOTT DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER VIDEO DESIGNER BUNNY CHRISTIE PAULE CONSTABLE FINN ROSS MOVEMENT DIRECTORS MUSIC SOUND DESIGNER SCOTT GRAHAM AND ADRIAN SUTTON IAN DICKINSON STEVEN HOGGETT FOR AUTOGRAPH FOR FRANTIC ASSEMBLY ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR RESIDENT DIRECTOR ELLE WHILE KIM PEARCE COMPANY VOICE WORK DIALECT COACH CASTING CHARMIAN HOARE JEANNETTE NELSON JILL GREEN CDG The Cast Christopher Boone JOSHUA JENKINS SAM NEWTON* Siobhan JULIE HALE Ed DAVID MICHAELS Judy -

City Research Online

Keeble, R. (1996). The Gulf War myth: a study of the press coverage of the 1991 Gulf conflict. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) City Research Online Original citation: Keeble, R. (1996). The Gulf War myth: a study of the press coverage of the 1991 Gulf conflict. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/7932/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. The Gulf war myth A study of the press coverage of the 1991 Gulf conflict by Richard Keeble PhD in Journalism May 1996; Department of Journalism, City University, London CONTENTS Abstract ix Acknowledgements x Introduction xi-iii A.1 The war problematic xi -

January 2017 Newsletter

January 2017 Newsletter QUICK LINKS Letter from the Chair Letter from Chair As we anticipate the 2017 Spring OLLI Op: James Joyce's Semester, I wish all of you a happy Birthday and healthy new year. The Spring OLLI Interview Semester promises to be a great one, Kenwood Country Club with 91 diverse study groups. We are Member? very grateful to our wonderful volunteer SGLs and OLLI Calendar Curriculum Committee who work so hard to bring these courses to the OLLI membership. And we are once again amazed at the artistry of Mary Fran Kenwood Country Miklitsch, who designed the wonderfully attractive catalog. We also thank our past Chair Gloria Club Member? Kreisman, dedicated editor of the catalog. Spring Are you a member of the registration ends Feb. 9. Choosing six courses and Kenwood Country Club? listing them in priority order greatly increases your If so, would you contact chance of being assigned three courses. the office at 202-895- 4860. You also should have received the Shorts catalog, which like the Spring catalog is online. Many thanks to Bob Coe for organizing the record number, OLLI Op: James amazing 17 Shorts. Registration for the Shorts ends Joyce's Birthday very shortly — January 18 — so register now. Our OLLI birthday party for James Joyce will take Once again, Denise Liebowitz and her lecture place on Thursday, Feb. committee are presenting first-rate lectures this 2, in Classroom A on the January. You can register for a week’s lectures on the 1st Floor. The schedule: Friday before the lectures at 9:00 am. -

The United Kingdom: Issues for the United States

Order Code RL33105 The United Kingdom: Issues for the United States Updated July 16, 2007 Kristin Archick Specialist in European Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division The United Kingdom: Issues for the United States Summary Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress view the United Kingdom as Washington’s staunchest and most reliable ally. This perception stems from a combination of factors: a shared sense of history and culture; the extensive bilateral cooperation on a wide range of foreign policy, defense, and intelligence issues that has developed over the course of many decades; and more recently, from the UK’s strong support in countering terrorism and confronting Iraq. The United States and Britain also share a mutually beneficial trade and economic relationship, and are each other’s biggest foreign direct investors. Nevertheless, some policymakers and analysts on both sides of the Atlantic question how “special” the “special relationship” is between Washington and London. Former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair — who stepped down on June 27, 2007 — sought to build a good rapport with the Bush Administration to both maximize British influence on the global stage, and to strengthen the UK as the indispensable “bridge” between the United States and Europe. But many British critics charged that Blair received little in return for his strong support of controversial U.S. policies. Some suggest that new British Prime Minister Gordon Brown may be less likely to allow the United States to influence UK foreign policy to the same degree as did Blair, given the ongoing UK public unease with the war in Iraq and the Bush-Blair alliance. -

Problems in British Foreign Policy

Heritage Special Report SR-xx SR-95 Published by The Heritage Foundation JuneMarch 6, XX, 2011 2011 Problems in British Foreign Policy By Dr. Robin Harris The Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom The Heritage Foundation is a research and educational institution—a think tank—whose mission is to formulate and promote conservative public policies based on the principles of free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional American values, and a strong national defense. Our vision is to build an America where freedom, opportunity, prosperity, and civil society flourish. As conservatives, we believe the values and ideas that motivated our Founding Fathers are worth conserving. As policy entrepreneurs, we believe the most effective solutions are consistent with those ideas and values. This paper is part of the American Leadership Initiative, one of 10 Transformational Initiatives making up The Heritage Foundation’s Leadership for America campaign. For more products and information related to these Initiatives or to learn more about the Leadership for American campaign, please visit heritage.org. Problems in British Foreign Policy By Dr. Robin Harris About the Author Dr. Robin Harris served during the 1980s as an adviser at the United Kingdom Treasury and Home Office, as Director of the Conservative Party Research Department, and as a member of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s Downing Street Policy Unit. He continued to advise Lady Thatcher after she left office and has edited the definitive volume of her Collected Speeches. Dr. Harris is now an author and journalist. His books include Dubrovnik: A History (Saqi Books, 2003); Beyond Friendship: The Future of Anglo–American Relations (The Heritage Foundation, 2006); and Talleyrand: Betrayer and Saviour of France (John Murray, 2007). -

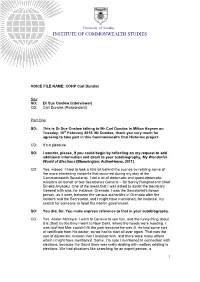

Institute of Commonwealth Studies

University of London INSTITUTE OF COMMONWEALTH STUDIES VOICE FILE NAME: COHP Carl Dundas Key: SO: Dr Sue Onslow (Interviewer) CD: Carl Dundas (Respondent) Part One: SO: This is Dr Sue Onslow talking to Mr Carl Dundas in Milton Keynes on Tuesday, 10th February 2015. Mr Dundas, thank you very much for agreeing to take part in this Commonwealth Oral Histories project. CD: It’s a pleasure. SO: I wonder, please, if you could begin by reflecting on my request to add additional information and detail to your autobiography, My Wonderful World of Elections [Bloomington: AuthorHouse, 2011]. CD: Yes, indeed. I tried to look a little bit behind the scenes by relating some of the more interesting incidents that occurred during my stay at the Commonwealth Secretariat. I did a lot of diplomatic and quasi-diplomatic missions on behalf of two Secretaries General – Sir Sonny Ramphal and Chief Emeka Anyaoku. One of the areas that I was asked to assist the Secretary General with was, for instance, Grenada. I was the Secretariat’s liaison person, as it were, between the various authorities in Grenada after the incident and the Secretariat, and I might have mentioned, for instance, my search for someone to head the interim government. SO: You did, Sir. You make express reference to that in your autobiography. CD: Yes. Alister McIntyre: I went to Geneva to see him, and the funny thing about it is [that] by the time I went to New Delhi, where the heads were meeting, I was told that Mac couldn’t fill the post because he was ill. -

In Theatre, Fiction Is Being Underrated (By Lyn Gardner, the Guardian, 26/05/2014)

In theatre, fiction is being underrated (by Lyn Gardner, The Guardian, 26/05/2014) Verbatim plays are lauded, but they are no more true as theatre than fiction, or even a combination of both: it's story that matters. One of the errors that verbatim theatre often makes is to conclude that because something is true, it is more interesting. Or rather, more interesting than something that has been made up. It's like those Hollywood movie openings that tell you the film you are about to see is "based on a true story". Why should that give it any more currency than a story that has been entirely made up and yet feels as if it's real – or more real than real? After all, imagination is the currency of all writers and theatre-makers. The interest in London Road – revived next week by Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, in what is a very brave choice – is not merely in the fact that it is based on interviews with people living in Ipswich in the wake of the murders of several young women, but in its musical form. The Nature Theatre of Oklahoma's Life and Times is fascinating as a theatre experience, not because it is based on 16 hours of phone conversations with a young woman called Kristen Worrell, but because of the way it shapes and presents that lived experience in multiple formats from country house murder mystery to illuminated manuscript. Both shows recognise that even when based on somebody else's words, the truth exists not inherently in the words themselves but in the way they are offered up to us, in what is unspoken or lies beneath them. -

Legacy of Margaret Thatcher: Not for Turning by Robin Harris

LECTURE DELIVERED SEPTEMBER 24, 2013 No. 1237 | DECEMBER 11, 2013 Not for Turning: The Life of Margaret Thatcher Dr. Robin Harris Abstract Margaret Thatcher is one of the most significant political figures of the Key Points 20th century, a Prime Minister whose impact on modern British histo- ry is comparable only to Winston Churchill’s and whose legacy remains ■■ Margaret Thatcher was a con- servative radical: Unlike the a massive political force even today. Robin Harris provides a definitive old-fashioned Tories, who want look at this indomitable woman: her hard-fought political battles, the to be something, she wanted tribulations of the miners’ strike and the Falklands War, her relation- to do something, to make a ship with Ronald Reagan and their shared opposition to Communism, difference. and the reality behind the scenes at Ten Downing Street, as well as one ■■ She was direct and honest. of the darkest hours of her premiership when she refused to alter course, She believed in character. She summing up for admirers and detractors alike the determination and believed in the virtues and in consistency of her approach with the words, “You turn if you want to. many ways represented in her The Lady’s Not for Turning.” whole life and her style of poli- tics the “vigorous virtues.” hank you all for coming. Thank you very much to the Heritage ■■ Endowed with great moral and TFoundation for hosting and organizing this event. A particular political courage, she reversed thank you to Ed Feulner and Heritage for tolerating me for the last Britain’s economic decline, five years or so—an occasionally visiting Brit who loves America and worked with American Presi- loves Heritage. -

Thesis Final

Historicising Neoliberal Britain: Remembering the End of History A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Christopher R Vardy School of Arts, Languages and Cultures List of Contents Abstract 4 Declaration and Copyright Statement 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction – Remembering the End of History Historicising neoliberal Britain 8 ‘Maggie’, periodisation and collective memory of the 1980s 15 Thatcherism and Neoliberalism 23 The End of History 28 Historical fictions, historicisation and historicity 34 Thesis structure 37 Chapter One – The End of History Introduction: Origin Myth 40 Histories 44 Fictions 52 Historicising the End of History 59 Struggle and inevitability 66 A War of Ghosts / History from Below 72 Conclusion: Historicity without futurity 83 Chapter Two – No Future Introduction: ‘Our little systems have their day; They have their day and cease to be’ 86 Bodily permeabilities 94 The financialised imaginary 97 Shaping the 1980s: reprise and the ‘light of the moment’ 104 Cocaine economics 110 Embodied crises of futurity 115 Conclusion: Dissonance 121 Chapter Three – Thatcher’s Children: Neoliberal Adolescence Introduction: Genesis or Preface? 123 2 Retro-memory 126 ‘You’ve obviously forgotten what it’s like’ 132 The nuclear 1980s 137 A brutal childhood 142 Adolescence and critique 147 Conclusion: Perpetual Adolescence 156 Chapter Four – Thatcher’s Children: Abusive Historicity Introduction: ‘Lost Boys’ and the arrested bildungsroman 158 The historical child: uses and abuses 162 Precarious Futures: Death of a Murderer 171 Re-writing the James Bulger murder: ‘faultline narratives’ and The Field of Blood 175 Cycles of abuse: Nineteen Eighty Three 183 Conclusion: Abusive historicity 188 Conclusion – Dissonance and Critique 189 Works cited 195 Word count: 72,506 3 Abstract This thesis argues that a range of twenty-first-century British historical fictions historicise contemporary neoliberal politics, economics and subject-formation through a return to the Thatcherite past. -

The Border Learning Resource Pack (2019) by Joseph Raynor

Learning Resource Pack Contents: Introduction to Theatre Centre, p2 The Creative Team (Who’s Who), p2 The Cast (Who’s Who), p5 The Border- What’s it about?, p6 Page-to-Stage, p7 Inside Rehearsals, p9 Design Process, p10 Design Scrapbook, p12 Set Design Storyboard, p14 Lesson Plans, p17 - p28 - Lesson 1: Exploring Characters, p17 Character Workshop Profile, p19 - Lesson 2: Exploring Themes, p20 - Lesson 3: Brecht & Epic Theatre Devices, p22 Extract 1, p24 Extract 2, p25 - Lesson 4: Devising Our Own Stories, p26 Extract 3, p28 Brecht the practitioner, p29 - p30 - Introduction to Brecht, p29 - Key facts, p30 Borders, p31 - Borders across world / history - Class discussion points The Border Learning Resource Pack (2019) by Joseph Raynor 1 www.theatre-centre.co.uk Introduction to Theatre Centre Theatre Centre brings world class theatre straight into the heart of schools. We make productions with big heart that empower children and young people to think, act, and speak for themselves. We design practical encounters with students and teachers which educate them on theatre practice, creative skills and activism. We are experts in touring, going everywhere, so all children and young people can see excellent live theatre. The Creative Team These are the people who have been working behind the scenes to create our production. Although you won’t see them on stage, without their work and creativity we wouldn’t have a production to perform. Afsaneh Gray | Playwright Afsaneh is a playwright and screenwriter. She is currently under commission by the Unicorn Theatre and the BBC. Her 2017 production Octopus transferred to London’s prestigious Theatre503 after a hugely successful run at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.