Redesigned Wine Labels and Consumer Preferences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loire Valley

PREVIEWCOPY Introduction Previewing this guidebook? If you are previewing this guidebook in advance of purchase, please check out our enhanced preview, which will give you a deeper look at this guidebook. Wine guides for the ultra curious, Approach Guides take an in-depth look at a wine region’s grapes, appellations and vintages to help you discover wines that meet your preferences. The Loire Valley — featuring a compelling line-up of distinctive grape varieties, high quality winemaking and large production volumes — is home to some of France’s most impressive wines. Nevertheless, it remains largely overlooked by the international wine drinking public. This makes the region a treasure trove of exceptional values, just waiting to be discovered. What’s in this guidebook • Grape varieties. We describe the Loire’s primary red and white grape varieties and where they reach their highest expressions. • Vintage ratings. We offer a straightforward vintage ratings table, which affords high-level insight into the best and most challenging years for wine production. • A Loire Valley wine label. We explain what to look for on a Loire Valley wine label and what it tells you about what’s in the bottle. • Map and appellation profiles. Leveraging our map of the region, we provide detailed pro- files of appellations from all five of the Loire’s sub-regions (running from west to east): Pays Nantais, Anjou, Saumur, Touraine and Central Vineyards. For each appellation, we describe the prevailing terroir, the types of wine produced and what makes them distinctive. • A distinctive approach. This guidebook’s approach is unique: rather than tell you what specific bottle of wine to order by providing individual bottle reviews, it gives the information you need to make informed wine choices on any list. -

June 2016 Wine Club Write.Pages

HIGHLAND FINE WINE JUNE 2016 HALF CASE - RED Domaine Landron Chartier ‘Clair Mont’ – Loire Vin de Pays, France (Mixed & Red Club) $17.99 The ‘Clair Mont’ is made up of mostly Cabernet Franc with a bit of Cabernet Sauvignon in the blend. Cabernet Franc is grown all over the Loire Valley and is a parent of its more famous progeny, Cabernet Sauvignon. Cabernet Franc in the Loire Valley is much lighter and fresh. The grape is early ripening and as a result has typically lower sugar levels at harvest, which producers lower alcohol wines. This wine is perfect for Cabernet Sauvignon drinkers who want lighter wines during the summer. It has all of the flavor components of Cabernet Sauvignon without the full tannins. This wine is great for grilling burgers and hotdogs or with Flank steak. Ryan Patrick Red – Columbia Valley, Washington (Mixed & Red Club) $11.99 This red is a blend of 71% Cabernet Sauvignon, 25% Merlot, 4% Malbec, and 1% Syrah. It is a blend typical of Columbia Valley which is known more for Bordeaux varietals such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. In fact Columbia Valley and Bordeaux are on roughly the same longitude, which means they have some similar climactic traits. Like Bordeaux, Columbia Valley is known for a more rounded style of red wine compared to the sun drenched wines of Napa Valley. This blend has a smooth texture with raspberry and dark cherry flavors, and has a dry, fruity finish. I like this wine with a slight chill to bring out the fruit. Calina Carmenere Reserva – Valle del Maule, Chile (Mixed & Red Club) $10.99 Carmenere has become the varietal of choice from Chile. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

Varieties Common Grape Varieties

SPECIALTY WINES AVAILABLE AT THESE LOCATIONS NH LIQUOR COMMISSION WINE EDUCATION SERIES WINE & REGIONS OF THE WORLD Explore. Discover. Enjoy. Varieties COMMON GRAPE VARIETIES Chardonnay (shar-doe-nay´) Famous Burgundy grape; produces medium to full bodied, dry, complex wines with aromas and tastes of lemon, apple, pear, or tropical fruit. Wood aging adds a buttery component. Sauvignon Blanc (so-vin-yawn´ blawn) Very dry, crisp, light-to-medium-bodied bright tasting wine with flavors of gooseberry, citrus and herbs. Riesling (reese´-ling) This native German grape produces light to medium- bodied, floral wines with intense flavors of apples, elcome to the peaches and other stone fruits. It can range from dry world of wine. to very sweet when made into a dessert style. One of the most appeal- Gewürztraminer (ge-vurtz´-tram-mih´-nur) ing qualities of wine is Spicy, medium-bodied, fresh, off-dry grape; native to the Alsace Region of France; also grown in California. the fact that there is such an Goes well with Asian foods. enormous variety to choose Pinot Gris (pee´-no-gree) from and enjoy. That’s why Medium to full bodied depending on the region, each New Hampshire State produces notes of pear and tropical fruit, and has a full finish. Liquor and Wine Outlet Store of- Pinot Blanc (pee´-no-blawn) fers so many wines from all around Medium-bodied, honey tones, and a vanilla finish. the world. Each wine-producing region Chenin Blanc (shay´-nan-blawn) creates varieties with subtle flavors, Off-dry, fruity, light-bodied grape with a taste of melon textures, and nuances which make them and honey; grown in California and the Loire Valley. -

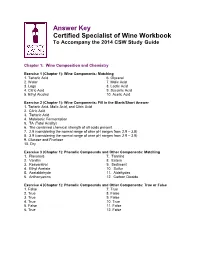

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook to Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide

Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2014 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2 (Chapter 1): Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, and Citric Acid 2. Citric Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present. 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4 (Chapter 1): Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Exercise 5: Checkpoint Quiz – Chapter 1 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1 (Chapter 2): Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. -

Wine Labels and Consumer Culture in the United States

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 7.1. | 2018 Visualizing Consumer Culture Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States Eléonore Obis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1029 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference Eléonore Obis, « Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States », InMedia [Online], 7.1. | 2018, Online since 20 December 2018, connection on 08 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/inmedia/1029 This text was automatically generated on 8 September 2020. © InMedia Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States 1 Wine labels and consumer culture in the United States Eléonore Obis Introduction Preliminary remarks 1 The wine market is a rich object of study when dealing with the commodification of visual culture. Today, it has to deal with a number of issues to promote wine, especially market segmentation, health regulations and brand image. First, it is important to find the right market segment as wine can be a luxury, collectible product that people want to invest in.1 At the other end of the spectrum, it can be affordable and designed for everyday consumption (table wine). The current trend is towards democratization and convergence in the New World, as wine and spirits consumption is increasing in countries that traditionally drink beer.2 Second, the market has to reconcile pleasure with health legislations imposed by governments and respect the health regulations of the country. The wine label is the epitome of this tension between what regulations impose and what the winemaker intends to say about the wine in order to sell it. -

Wine Label Design Preferences and Purchase Behavior Of

WINE LABEL DESIGN PREFERENCES AND PURCHASE BEHAVIOR OF MILLENNIALS A Thesis by KAYLAN MARIN MILLIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Billy R. McKim Committee Members, Tobin D. Redwine Suresh Ramanathan Head of Department, Clare Gill December 2018 Major Subject: Agricultural Leadership, Education, and Communications Copyright 2018 Kaylan Marin Millis ABSTRACT Marketers of wine companies are expanding their efforts to capture the newest generation of wine drinkers, Millennials. Further research is needed to understand this generation as wine consumers. In this study, we investigated the factors that influence Millennials’ wine purchasing behavior and what characteristics of wine labels are most desirable, unattractive, and appear valuable to Millennials. Also, virtual reality incorporated into wine labels is a new marketing phenomenon. Little or no evident research has been done to understand if this adds value to a product and encourages Millennials to recommend the wine or purchase it. The target population for this study was Millennials between the ages of 21 and 37, and the sample consisted of 68 self- selected participants. A cross-sectional, quantitative, case study design was used and data were collected using two methods: Tobii Pro X2-60 eye tracking and a questionnaire. Based on the results of this study, we concluded Millennials purchase and/or consume wine weekly or multiple times per month. Millennials reported spending between $10.00 - $14.99 per bottle of wine, and the majority of the participants purchased their wine at the grocery store. -

Wine Beverage Alcohol Manual 08-09-2018

Department of the Treasury Alcohol & Tobacco Tax & Trade Bureau THE BEVERAGE ALCOHOL MANUAL (BAM) A Practical Guide Basic Mandatory Labeling Information for WINE TTB-G-2018-7 (8/2018) TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE OF THE BEVERAGE ALCOHOL MANUAL FOR WINE, VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION, WINE BAM GOVERNING LAWS AND REGULATIONS CHAPTER 1, MANDATORY LABEL INFORMATION Brand Name ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 Class and Type Designation ........................................................................................................ 1-3 Alcohol Content ........................................................................................................................... 1-3 Percentage of Foreign Wine ....................................................................................................... 1-6 Name and Address ..................................................................................................................... 1-7 Net Contents ................................................................................................................................ 1-9 FD&C Yellow #5 Disclosure ........................................................................................................ 1-10 Cochineal Extract or Carmine ...................................................................................................... 1-11 Sulfite Declaration ...................................................................................................................... -

Checklists for International Markets

Checklists for International Markets Labelling Workshop Presenters Belinda van Eyssen & Rebecca Fox 16 July 2013 Wine Label Overview US market Legless Bubbly A delightful sparkling wine produced by the traditional method and blended at our state of the art Yarra Valley facility from a blend 84% Chardonnay and 10% Pinot Noir. GOVERNMENT WARNING: (1) According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects. (2) Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery, 2011 and may cause health problems. Sparkling Contains Sulfites Chardonnay Pinot Noir Imported by: Jo Black, San Francisco California South Eastern Australia Wine of Australia 10.5% Alc./Vol. 750mL. USA Label Checklist Checklist Item Format Checked? 1 Alcohol Statement 2 Volume Statement 3 Country of Origin 4 Brand Label 5 Sulphite Statement 6 Government Warning 7 Importer Name & Address 8 Lot Number 9 Product Designation 10 Prohibited Items 11 Vintage, Variety & Geographical Indication 12 Brand name 13 Protected Terms 14 Organic Claims Labelling Checklist Mandatory Description To comply with the label requirement the brand name, alcohol, designation (i.e. Brand Label Variety) and geographical indication must all appear on the one label Format is prescribed as ‘xx.x% alc./vol.’ or ‘alc xx.x% by vol’. The statement must Alcohol Statement be between 1-3mm in height. The volume statement must be at least 2mm for the USA. May appear on the Nominal Volume front or back label. Country of Origin Format not prescribed. May appear on any label. Mandatory if vintage(or variety) is claimed. -

NAVARRO Vineyards

NAVARRO Vineyards 2009 Navarro Brut, Anderson Valley: Act two 2010 Chardonnay, Première Reserve: What’s in a name? 2011 Gewürztraminer, Estate Bottled, (Dry): Shy bearer yields bold perfume 2011 Chardonnay Table Wine: Morning star 2011 Pinot Gris, Anderson Valley: Shady lady 2010 Pinot Noir, Méthode à l’Ancienne: Whose woods are these? 2010 Shiraz, Mendocino: Searching Down Under 2010 Zinfandel, Mendocino: The new young 2011 Riesling, Cluster Select Late Harvest: Wine of the Year 2012 Grape Juices, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Noir and Verjus: Juice stand Pennyroyal Farmstead Cheese: Where every goat has a name 2009 Navarro Brut 100% Gewürztraminer Anderson Valley, Mendocino OUR 2012 HOLIDAY RELEASES Say cheese avarro’s newsletter is a little thicker this year since the last four pages are devoted to the farmstead cheeses that our family is now producing at Pen- Nnyroyal Farm in Boonville. In addition to Pennyroyal cheese, Navarro has nine new wine releases: four dry whites, three Gewürztraminer is Navarro’s flag- vigorous reds, a luscious late harvest nectar and a sparkling ship grape. Aging Brut as a special holiday treat. We are also releasing three en tirage allows yummy varietal grape juices so all of the family can share in the intriguing the celebrations. The case specials on the 2011 Chardonnay flavor of autolyzed Table Wine and 2010 Mendocino Shiraz works out to only yeast to slowly develop in the wine. $10.50 and $13.50 per bottle respectively, which explains why they will grace the holiday tables of so many of Navarro’s long- term friends. Since we’re all counting pennies, One-Cent Act two ground freight and reduced air freight n 2009 we harvested Gewürztraminer at a perfect ripeness for sparkling for all case orders, as wine. -

Predicting Wine Prices from Wine Labels

Predicting Wine Prices from Wine Labels Jamie Ray1,*, Svetlana Lyalina2 and Ruby Lee2 1Department of Engineering Physics, Stanford University 2Department of Computer Science, Stanford University Submitted on December 14, 2012 and textual features from the wine notes, type, and origin. ABSTRACT We hope that future wine producers will be able to use such Motivation: The wine label is an icon that unites a model to inform their design decisions. powerful branding and fine design under a single image. With U.S. wine consumption predicted to increase to $23.8 billion by 2014, wine labels are used 2 METHODS & RESULTS not only to convey a given wine’s type, producer, and Data Collection. There are a number of online wine origin, but also its emotional and cultural appeal. Thus, shopping websites that have thousands of wines associated a wine label is carefully designed to convey the proper with price, origin, and producer of the bottle. These include messaging of a particular bottle, whether it is for the wine.com and winechateau.com. However, the images on casual consumer or the choosy collector. We have winechateau.com contain the entire wine bottle, while applied machine learning to the art of wine label wine.com has images of the label only. Thus, we decided to design by learning the design features which most scrape wine.com for all of its 30,000 wine labels and wine influence a bottle’s popularity and selling price. We name, price, type, varietal, appelation, region, and additional have collected over 30,000 wine labels and associated notes. -

Biodynamic Wines Or Wines Made with Biodynamic Grapes

How wineries are packaging their eco-credentials Tara Duggan, Chronicle Staff Writer Friday, November 14, 2008 Feel-good phrases like "responsible stewards of the land" and "family farmed for a sustainable world" take up a lot of real estate on the front label of Parducci's Sustainable Red. The back label features a checklist of the wine's eco-creds: locally farmed grapes, solar energy, earth-friendly packaging. A cardboard wrapping around the bottleneck seals the deal by proclaiming that it's made at the country's first carbon- neutral winery. Parducci - part of the Mendocino Wine Co. - is a dramatic example of how winemakers are choosing to communicate their sustainable practices. In the old days, wine associated with organic agriculture was left dusty on the shelf. But in this new era of eco-luxury, green is something to be proud of. Wineries are devising all kinds of ways to market their eco-practices. "In the early days, green was hippie and hemp," says Kevin George, founder of Articulate Design Inc. in San Francisco, who designed Lexus' Hybrid Living marketing program. But today, he says, "For discerning buyers there's a whole lot of choices they can make that can bring together luxury and sustainability." Organic and biodynamic vineyard certifications in California continue to grow at a steady pace, though they are eclipsed by the number of wineries involved in sustainable winegrowing programs, which more often involve self-monitoring rather than third-party certification. (See "Sustainable wine definitions," below) Whichever green path they chose, the challenge is deciding how to let the consumer in on what they're doing.