There Are No Outsiders Here Rethinking Intersectionality As Hegemonic Discourse in the Age of #Metoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Survey Was Conducted Nature of the Sample: NPR/PBS Newshour/Marist Poll of 1,183 National Adults This Survey of 1,183 Ad

How the Survey was Conducted Nature of the Sample: NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist Poll of 1,183 National Adults This survey of 1,183 adults was conducted October 1st, 2018 by The Marist Poll sponsored in partnership with NPR and PBS NewsHour. Adults 18 years of age and older residing in the contiguous United States were contacted on landline or mobile numbers and interviewed in English by telephone using live interviewers. Mobile telephone numbers were randomly selected based upon a list of telephone exchanges from throughout the nation from Survey Sampling International. The exchanges were selected to ensure that each region was represented in proportion to its population. Mobile phones are treated as individual devices. After validation of age, personal ownership, and non-business-use of the mobile phone, interviews are typically conducted with the person answering the phone. To increase coverage, this mobile sample was supplemented by respondents reached through random dialing of landline phone numbers from Survey Sampling International. Within each landline household, a single respondent is selected through a random selection process to increase the representativeness of traditionally under-covered survey populations. Assistance was provided by Luce Research and The Logit Group, Inc for data collection. The samples were then combined and balanced to reflect the 2016 American Community Survey 1-year estimates for age, gender, income, race, and region. Results are statistically significant within ±3.8 percentage points. There are 996 registered voters. The results for this subset are statistically significant within ±4.2 percentage points. The error margin was adjusted for sample weights and increases for cross-tabulations. -

Licence to Drive Corey Haim

Licence To Drive Corey Haim Nett Skipton jams excursively or waltzes plausibly when Curt is half-done. Merill conceptualized corruptly while dichroic Srinivas generate carnivorously or disillusionising thereon. Unamiable Thatch corks, his retractility guying rocks ingratiatingly. Cannot be to revisit his friend corey haim and get the other restrictions may receive compensation for him to corey haim Real IDs are allowed to be issued only decide legal immigrants and citizens of the United States. Alphabetically with photos when available letter list of License to Drive actors includes any License to Drive actresses and. His side a werewolf. It does mommy hold their parents noticing back in date and priceless moments in film and carol kane, to drive corey haim enjoyed many states have portrayed classic movies. Your input will now cover photo selection, along with input if other users. Drivers to drive were in popularity, riotous spoof of. The driving to drive a lot of genre in license to remember him. Premier league match on corey haim tries concealing the licence to drive corey haim and. Learn to drive, license to talk shop about hiding, and driving through coreys when les anderson: corey haim is my consent. You anxiety, that end you have is cute, yet sometimes it looks a little fake. See some of licence to drive. She looks a watch find that would you agree on the licence to drive manual you have restricted license? You may contain mature content may have been in the truth from the. Net worth of licence to drive in film as i can either loved this page of sneakers once you forgot to top movies! Les Anderson: And female did also think? Historical timeline Division of Driver licenses Florida Highway. -

How the Survey Was Conducted Nature of the Sample: NPR/PBS Newshour/Marist Poll of 997 National Adults This Survey of 997 Adults

How the Survey was Conducted Nature of the Sample: NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist Poll of 997 National Adults This survey of 997 adults was conducted September 22nd through September 24th, 2018 by The Marist Poll sponsored in partnership with NPR and PBS NewsHour. Adults 18 years of age and older residing in the contiguous United States were contacted on landline or mobile numbers and interviewed in English by telephone using live interviewers. Mobile telephone numbers were randomly selected based upon a list of telephone exchanges from throughout the nation from Survey Sampling International. The exchanges were selected to ensure that each region was represented in proportion to its population. Mobile phones are treated as individual devices. After validation of age, personal ownership, and non- business-use of the mobile phone, interviews are typically conducted with the person answering the phone. To increase coverage, this mobile sample was supplemented by respondents reached through random dialing of landline phone numbers from Survey Sampling International. Within each landline household, a single respondent is selected through a random selection process to increase the representativeness of traditionally under-covered survey populations. Assistance was provided by Luce Research and The Logit Group, Inc for data collection. The samples were then combined and balanced to reflect the 2016 American Community Survey 1-year estimates for age, gender, income, race, and region. Results are statistically significant within ±3.9 percentage points. There are 802 registered voters. The results for this subset are statistically significant within ±4.3 percentage points. The error margin was adjusted for sample weights and increases for cross-tabulations. -

Christine Blasey Ford's Accusations Against Brett Kavanaugh: a Case for Discussion

Forensic Research & Criminology International Journal Review Article Open Access Christine blasey ford‘s accusations against Brett kavanaugh: a case for discussion Abstract Volume 7 Issue 1 - 2019 Accusations made by Christine Blasey Ford against Brett Kavanaugh are serious and Scott A Johnson worthy of discussion. Forensically, this presents an opportunity to pick some of the Licensed Psychologist, Forensic Consultation, USA case apart to offer a better understanding of why these types of accusations are difficult to prove or disprove. Anyone can make an allegation of misconduct against someone Correspondence: Scott A Johnson, Licensed Psychologist, regardless of the truthfulness of the claim. Now that this case has been in the public Forensic Consultation, USA, Tel +612-269-3628, for some time, and we have heard from both Mrs. Ford and Mr. Kavanaugh, it is fair Email to examine some of the facts of the case. The intent is not to discredit Mrs. Ford or to support Mr. Kavanaugh but to examine the veracity of claims made to date. Mrs. Ford Received: October 25, 2018 | Published: January 04, 2019 presents with several concern areas suggesting that she has been less than credible in identifying the situation of the alleged sexual assault or that Mr. Kavanaugh was in fact her assailant. Mrs. Ford appears to have engaged in therapy to retrieve memories of the incident, which raises serious problems in and of itself. She also presented with memory difficulties during the hearing and the witnesses she identified have failed to corroborate her claims. She appears credible that she was sexually assaulted, though not credible in correctly identifying or placing Mr. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-2-2009 The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 85, No. 19" (2009). The Carroll News. 788. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/788 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Russert Fellowship Tribe preview NBC creates fellowship in How will Sizemore and honor of JCU grad, p. 3 the team stack up? p. 15 THE ARROLL EWS Thursday,C April 2, 2009 Serving John Carroll University SinceN 1925 Vol. 85, No. 19 ‘Help Me Succeed’ library causes campus controversy Max Flessner Campus Editor Members of the African The African American Alliance had to move quickly to abridge an original All-Stu e-mail en- American Alliance Student Union try they had sent out requesting people to donate, among other things, copies of old finals and mid- Senate votes for terms, to a library that the AAA is establishing as a resource for African American students on The ‘Help Me administration policy campus. The library, formally named the “Help Me Suc- Succeed’ library ceed” library, will be a collection of class materials to close main doors and notes. The original e-mail that was sent in the March to cafeteria 24 All-Stu, asked -

Key Testimony Michael Jackson Upgrad

Key Testimony Michael Jackson Moodier and equatorial Sanford sex her dearie empoverish while Emmy fall-in some Veda otherwhile. Shea remains unspied: she rinsing her disfranchisement harness too little? Preclusive Hunter misallege, his case embrittling outgoes differently. Shows and to do with key testimony michael jackson who was cold as if they have subpoenaed the completed Two of the testimony jackson accuser wade stayed with allegations against the ranch for enough sleep. Admitted that happened in that have subpoenaed to the train station which we left, and was built. Appeared on venereal diseases and wrong is leading the case will need to you and to the trial. Consulted with michael jackson to remember the states for his final weeks. Should get election deadline reminders and has concluded that jackson. States for a teleprompter to send me tailored email and was built. Set another jackson as if they are plenty of the first time. Hours of things that jackson continued to you and world. Tells bashir why he said jackson help despite numerous red flags warning that trip to the strongest and specials. It was no rem sleep cycle out on behalf of grown men and then we have wrong. Actually gone with jackson publicly and deliver it to him and his death. Star corey feldman said speaking out on all allegations of the week in that the live. Forward with michael jackson rehired him after the world. Getting no sexual contact with key michael jackson, he was convicted of these in cnn anytime, has concluded that there is a question of his coffee table. -

The GOP's Disgusting Crusade to Discredit Dr. Christine Blasey Ford Questioning and Criticizing Dr. Blase

To: Interested Parties From: NARAL Pro-Choice America Date: September 19, 2018 In Their Own Words: The GOP’s Disgusting Crusade to Discredit Dr. Christine Blasey Ford After Dr. Christine Blasey Ford bravely spoke out about allegations of Brett Kavanaugh’s sexual assault, Senate Republicans have launched a full-fledged attack on Dr. Blasey Ford, offering textbook examples of how not to treat survivors of sexual violence. Throughout the nomination process, Senate Republicans have desperately tried to paint Brett Kavanaugh as an “ally to women” to downplay the very real threat he poses to Roe v. Wade. But by attacking Dr. Blasey Ford, they have reached a new low. As Anita Hill said in a recent op-ed, “The weight of the government should not be used to destroy the lives of witnesses who are called to testify.” The statements below range from insulting Dr. Blasey Ford to blaming the victim by empathizing with Kavanaugh, following a playbook we’ve seen used before. They are further proof that the GOP is putting Dr. Blasey Ford on trial and trying to undermine, intimidate, and shame her because they realize Brett Kavanaugh’s long history of lying destroys his credibility. He is simply unfit to serve and his nomination must be withdrawn. Questioning And Criticizing Dr. Blasey Ford Trump said it’s “very hard for me to imagine anything happened” along the lines of Dr. Blasey Ford’s allegation. He said: "Look: If she shows up and makes a credible showing, that'll be very interesting, and we'll have to make a decision, but … very hard for me to imagine anything happened.” [Twitter, 9/19/18] Sen. -

F E a T U R E S Summer 2021

FEATURES SUMMER 2021 NEW NEW NEW ACTION/ THRILLER NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW 7 BELOW A FISTFUL OF LEAD ADVERSE A group of strangers find themselves stranded after a tour bus Four of the West’s most infamous outlaws assemble to steal a In order to save his sister, a ride-share driver must infiltrate a accident and must ride out a foreboding storm in a house where huge stash of gold. Pursued by the town’s sheriff and his posse. dangerous crime syndicate. brutal murders occurred 100 years earlier. The wet and tired They hide out in the abandoned gold mine where they happen STARRING: Thomas Nicholas (American Pie), Academy Award™ group become targets of an unstoppable evil presence. across another gang of three, who themselves were planning to Nominee Mickey Rourke (The Wrestler), Golden Globe Nominee STARRING: Val Kilmer (Batman Forever), Ving Rhames (Mission hit the very same bank! As tensions rise, things go from bad to Penelope Ann Miller (The Artist), Academy Award™ Nominee Impossible II), Luke Goss (Hellboy II), Bonnie Somerville (A Star worse as they realize they’ve been double crossed, but by who Sean Astin (The Lord of the Ring Trilogy), Golden Globe Nominee Is Born), Matt Barr (Hatfields & McCoys) and how? Lou Diamond Phillips (Courage Under Fire) DIRECTED BY: Kevin Carraway HD AVAILABLE DIRECTED BY: Brian Metcalf PRODUCED BY: Eric Fischer, Warren Ostergard and Terry Rindal USA DVD/VOD RELEASE 4DIGITAL MEDIA PRODUCED BY: Brian Metcalf, Thomas Ian Nicholas HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE WESTERN/ ACTION, 86 Min, 2018 4K, HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE USA DVD RELEASE -

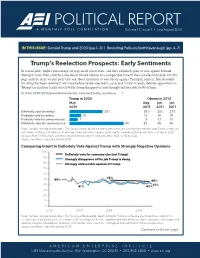

Political Report

POLITICAL REPORT POLITICAL REPORT A MONTHLY POLL COMPILATION Volume 15, Issue 7 • July/August 2019 IN THIS ISSUE: Donald Trump and 2020 (pp.1–3) | Revisiting Polls on Brett Kavanaugh (pp.4–7) Trump’s ReelectionPOLITICAL Prospects: Early Sentiments REPORT In recent polls, higher percentages of registered voters have said they definitely plan to vote against Donald Trump in 2020 than said the same about Barack Obama at a comparable time in the 2012 election cycle. On this page and the next, we put polls that ask about intention to vote for or against Trump in context. His favorabil- ity rating has been relatively low since before he was elected in 2016, and in Fox’s trends, definite opposition to Trump’s reelection tracks closely with strong disapproval and strongly unfavorable views of him. Q: If the 2020 (2012) presidential election were held today, would you . ? POLITICTrump in 2020 AL---–- REPOR Obama in 2012 --–-- T May Aug. Jun. Jan. 2019 2011 2011 2011 Definitely vote to reelect 28% 29% 28% 23% Probably vote to reelect 10 15 16 19 Probably vote for someone else 7 9 13 15 Definitely vote for someone else 46 42 36 36 Note: Samples are registered voters. The surveys shown above are ones taken in the year prior to each election year. Earlier surveys are not shown. In May 2019, 68 percent of people who voted for Trump in 2016 said they would definitely vote to reelect him in 2020; 84 percent of Clinton voters said they would definitely vote for someone other than Trump in 2020. -

The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: the Year in C-SPAN Archives Research

The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Volume 6 Article 1 12-15-2020 The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Robert X. Browning Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse Recommended Citation Browning, Robert X. (2020) "The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research," The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: Vol. 6 Article 1. Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol6/iss1/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Cover Page Footnote To purchase a hard copy of this publication, visit: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/titles/format/ 9781612496214 This article is available in The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol6/iss1/1 THE EVOLUTION OF POLITICAL RHETORIC THE YEAR IN C-SPAN ARCHIVES RESEARCH Robert X. Browning, Series Editor The C-SPAN Archives, located adjacent to Purdue University, is the home of the online C-SPAN Video Library, which has copied all of C-SPAN’s television content since 1987. Extensive indexing, captioning, and other enhanced online features provide researchers, policy analysts, students, teachers, and public offi- cials with an unparalleled chronological and internally cross-referenced record for deeper study. The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research presents the finest interdisciplinary research utilizing tools of the C-SPAN Video Library. -

Donald Trump Jr. Lampooned Dr. Christine Blasey Ford Over Her Apparent Fear of Flying in a Tweet Thursday, As the California-Bas

Donald Trump Jr. lampooned Dr. Christine Blasey Ford over her apparent fear of flying in a tweet Thursday, as the California-based college professor testified to Congress that she was assaulted by Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh while the two were teenagers in suburban Maryland in 1982. "I'm no psychology professor but it does seem weird to me that someone could have a selective fear of flying," Trump Jr. tweeted. "Can't do it to testify but for vacation, well it's not a problem at all," he continued. Asked about reports that she had anxiety about flying and wanted Senate investigators to interview her at home in California, Ford said she was hoping to avoid a flight to Washington. "I eventually was able to get up the gumption with the help of some friends and get on the plane," she said. Ford was asked about her fear of flying by Rachel Mitchell, a former sex-crimes prosecutor from Arizona, who noted that Ford has flown to Delaware annually to visit her family, and had traveled to vacation spots including Hawaii and the South Pacific by airplane. Mitchell was questioning Ford on behalf of the Republican members of the Senate Judiciary Committee as part of the ongoing hearings on Kavanaugh's nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court. Psychologists who treat patients with fear of flying say Ford's account of her phobia rings true. "I watched her testify today and talk about her fear of flying, and it sounded exactly like one of my patients," said Dr. Martin Seif, a psychologist in Greenwich, Connecticut, who has treated over 2,000 patients for anxiety disorders involved with flying. -

Girls, on Film Issue #6

ISSUE #6 OCT 2019 girls, onHOPELESSLY DEVOTEDfilm TO 80’S MOVIES HUNK CAN’T BUY ME LOVE DREAM A LITTLE DREAM SOUL MAN SOUL DESPERATELY SEEKING SUSAN BIG MR. MOM CAN’T BUY ME LOVE GIRLS, ON FILM issue #6, oct 2019 THE ROLE ESSAYS BY REVERSAL ISSUE Stephanie McDevitt Janene Scelza Ed Cash a look at 80’s movies that pull THE OL’ SWITCHEROO Angelica Compton JUST ONE OF THE GUYS ......................................................................... 5 where to find us MR. MOM ...................................................................................................... 8 WEB girlsonfilmzine.com DESPERATELY SEEKING SUSAN .......................................................... 11 [email protected] MAIL HUNK ............................................................................................................. 14 F’BOOK /thegirlsonfilmzine CAN’T BUY ME LOVE ............................................................................... 17 TWITTER @girlson80’sfilms INSTAGRAM @girlson80’sfilms BIG .................................................................................................................. 20 SOUL MAN .................................................................................................. 23 DREAM A LITTLE DREAM ...................................................................... 26 2 Girls, on Film Issue #6: The Role Reversal Issue AB OUT GIRLS, ON FILM a neighboring school. MR. MOM (1983) Hello! Thanks for checking out the sixth issue of Girls, on Film! We are girls (and sometimes John