Ghanaian Methodist Spirituality in Relation with Neo- Pentecostalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pentecost Event in Acts 2: Significance for Contemporary Christian Missions Paul Kang-Ewala Diboro1

June 2019 Issue Volume 1 Number 2 ISSN 2458 – 7338 Article 10 pp 100 – 111 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32051/06241910 © 2019 Copyright held by ERATS. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ THE PENTECOST EVENT IN ACTS 2: SIGNIFICANCE FOR CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MISSIONS PAUL KANG-EWALA DIBORO1 ABSTRACT The Pentecost Event in the Acts of the Apostles has been interpreted from many perspectives within the context of the Pentecost text. Accordingly, the issues raised from the interpretations focused on the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, empowerment for missions, the emphasis on the vernacular language for the apprehension and comprehension of the Christian faith among others. These issues are based on the interpretation of the happenings on the day of Pentecost in Acts. This article attempts to draw attention to the significance of Pentecost Event in the light of contemporary Christian missions particularly in Africa. The article engages the Pentecost narrative or text (Acts 2:1-13) critically and exegetically to unearth its contemporary significance. It argues that, the happenings on the day of Pentecost is the root of Pentecostalism. Some theological and linguistic, missiological and ecclesiological significance are noted and discussed. INTRODUCTION The interpretations and analyses of the Pentecost narrative in Acts chapter two has gained a lot of scholarly attention recently. Accordingly, the issues raised from the interpretations and analyses focused on the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, empowerment for missions, the emphasis on the vernacular language for the apprehension and comprehension of the Christian faith2 among others. This article attempts to examine the Pentecost event in Acts of the Apostles and its significance for contemporary missions particularly in Africa. -

Ghana Gazette

GHANA GAZETTE Published by Authority CONTENTS PAGE Facility with Long Term Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 1236 Facility with Provisional Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 201 Page | 1 HEALTH FACILITIES WITH LONG TERM LICENCE AS AT 12/01/2021 (ACCORDING TO THE HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND FACILITIES ACT 829, 2011) TYPE OF PRACTITIONER DATE OF DATE NO NAME OF FACILITY TYPE OF FACILITY LICENCE REGION TOWN DISTRICT IN-CHARGE ISSUE EXPIRY DR. THOMAS PRIMUS 1 A1 HOSPITAL PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI KUMASI KUMASI METROPOLITAN KPADENOU 19 June 2019 18 June 2022 PROF. JOSEPH WOAHEN 2 ACADEMY CLINIC LIMITED CLINIC LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE MAMPONG KUMASI METROPOLITAN ACHEAMPONG 05 October 2018 04 October 2021 MADAM PAULINA 3 ADAB SAB MATERNITY HOME MATERNITY HOME LONG TERM ASHANTI BOHYEN KUMASI METRO NTOW SAKYIBEA 04 April 2018 03 April 2021 DR. BEN BLAY OFOSU- 4 ADIEBEBA HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG-TERM ASHANTI ADIEBEBA KUMASI METROPOLITAN BARKO 07 August 2019 06 August 2022 5 ADOM MMROSO MATERNITY HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI BROFOYEDU-KENYASI KWABRE MR. FELIX ATANGA 23 August 2018 22 August 2021 DR. EMMANUEL 6 AFARI COMMUNITY HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI AFARI ATWIMA NWABIAGYA MENSAH OSEI 04 January 2019 03 January 2022 AFRICAN DIASPORA CLINIC & MATERNITY MADAM PATRICIA 7 HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI ABIREM NEWTOWN KWABRE DISTRICT IJEOMA OGU 08 March 2019 07 March 2022 DR. JAMES K. BARNIE- 8 AGA HEALTH FOUNDATION PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI OBUASI OBUASI MUNICIPAL ASENSO 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 DR. JOSEPH YAW 9 AGAPE MEDICAL CENTRE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI EJISU EJISU JUABEN MUNICIPAL MANU 15 March 2019 14 March 2022 10 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION -ASOKORE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE KUMASI METROPOLITAN 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION HOSPITAL- DR. -

5 Starter Facts About Pentecostal Christianity

5 Starter Facts About Pentecostal Christianity 1. Pentecostalism is was born out of the evangelical revival movements of the late 19th century. There are ~13 million adherents in the United States and ~279 million worldwide. 2. There is no central governing body for Pentecostalism, but many churches belong to the Pentecostal World Fellowship. Most Pentecostals believe they practice a pure and simple form of Christianity, like the earliest stages of the Christian Church. They believe the Bible is the word of God and completely without error. 3. Speaking/interpreting tongues, prophecy, and healing are believed to be gifts from the divine. During worship, Pentecostals allow and even encourage dancing, shouting, and praying aloud. Many believe in lively worship because of the influence of the Holy Spirit. There is praying aloud, clapping and shouting, and sometimes oil anointments. 4. There is a great amount of variety within Pentecostalism due to questions over the trinity vs oneness of deity and whether upholding divine healing means modern medicine should be rejected or embraced. 5. The day of Pentecost, the namesake of the denomination, is the baptism of the twelve disciples by the Holy Spirit. It is celebrated as a joyous festival on the Sunday 50 days after Easter. Learn more at: http://pentecostalworldfellowship.org/about-us http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/subdivisions/pentecostal_1.shtml These five points are not meant to be comprehensive or authoritative. We hope they encourage you to explore this spirituality more deeply and seek out members of this community to learn about their beliefs in action. -

Notes Weekly Bible Lessons

Weekly Bible Lessons Notes Scripture, unless otherwise indicated, is taken from THE HOLY BIBLE NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Bible Publishers. All rights reserved. All comments, enquiries and suggestions may be directed to: The Head, Educational Resource Development Department Freeman Centre for Missions and Leadership Development, P. O. Box 413, Kumasi, Ghana. Telephone: (051) 23014, 20968 Email: [email protected] Copyright © The Methodist Church Ghana January - June 2010 1 148 The Weekly Bible Lessons is produced biannually by the Educational Resource Development Department of the Freeman Centre for Missions and Leadership Development of The Methodist Church Ghana, under the supervision and over- sight of the Board of Ministries of the Church. This booklet is designed to facili- tate and enhance organised group Bible studies, within group (class) meetings Notes and personal devotion. Review Editor Our Writers The following writers made significant contributions to this edition of Weekly Bible Lessons, January-June 2010. Right Reverend Professor O. Safo-Kantanka, BSc., MSc., PhD. , Diocesan Bishop, Kumasi Diocese Very Reverend Dr. Paul Kwabena Boafo, BA. , Chaplain, KNUST, Kumasi. Very Reverend G. K. Abeyie Sarpong, BA., Superintendent Minister, Tutuka Circuit, Obuasi Diocese. Very Reverend (Mrs). Comfort Ruth Quartey-Papafio, MTS., ThM., Kasoa Circuit, Winneba Diocese. Very Reverend James K. Walton, BSc., MDiv., Headmaster, Methodist Day Senior High School, Tema. Rev. Daniel Kwasi Tannor, BA., MPhil., Lecturer, Christian Service University College, Kumasi. Rev. Richard E. Amissah, Evangelism Coordinator, Kumasi Diocese. Rev. Kwame Amoah Mensah., B.Ed., Diocesan Youth Organizer, Kumasi Diocese. Rev. Mark S. Aidoo, BD., MTh., Student, Princeton Theological Seminary, USA. -

Roman Catholicism Versus Pentecostalism: the Nexus of Fundamentalism and Religious Freedom in Africa

Verbum et Ecclesia ISSN: (Online) 2074-7705, (Print) 1609-9982 Page 1 of 7 Original Research Roman Catholicism versus Pentecostalism: The nexus of fundamentalism and religious freedom in Africa Author: Today’s Christians in the age of secularism and other kinds of ideologies struggle to make 1 Felix E. Enegho their impacts felt as they assiduously labour to plant the gospel in the hearts and minds of Affiliation: many. Amid their struggles and worries, they are often confronted with other challenges 1Department of Christian both from within and outside. The aim of this research was to assess the Roman Catholic Spirituality, Church History Church and her struggle in the midst of other Churches often tagged ‘Pentecostals’ in the and Missiology, Faculty of areas of fundamentalism and religious freedom in Africa and most especially in Nigeria. Human Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, Pentecostal theology was aligned with Evangelism in their emphasis on the reliability of the South Africa Bible and the great need for the spiritual transformation of the individual’s life with faith in Jesus Christ. They emphasise personal experience and work of the Holy Spirit and therefore Corresponding author: see themselves as a selected few, who are holy, spiritual and better than others. Some of them Felix Enegho, [email protected] even claim to have the monopoly of the Holy Spirit. This researcher was one scholar who holds the view that there was no church more Pentecostal than the Catholic Church which Dates: has survived for more than 2000 years under the influence and direction of the Holy Spirit. -

Changes in the Music of the Liturgy of the Methodist Church Ghana: Influences on the Youth

American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2019 American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-02, Issue-04, pp-30-35 April-2019 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access Changes In The Music Of The Liturgy Of The Methodist Church Ghana: Influences On The Youth Daniel S. Ocran Methodist University College Dansoman Accra Ghana *Corresponding Author: Daniel S. Ocran ABSTRACT: This paper examines the current liturgy of the Methodist Church to ascertain how the youth of today have been influenced by the musical content. Musical traditions of the Methodist Church such as ebibindwom, hymns and canticles, anthems, danceable tunes from the singing band and other liturgical musical elements present in the Methodist ChurchGhana, will critically be reviewed to realise the response of the youths. The methodology of the research will include visits to selected churches in selected dioceses, interviews of choirmasters and singing band masters selected members from the congregation as well as local preachers and Reverend, Ministers to find out about how they perceive the youths response to the variants of musical styles on the liturgy. The findings will go a long way to enlighten, reform and educate various Methodist youth to adjust to the new Order of Service. I. PREAMBLE This work has four sections: the first two sections discuss the ministration and involvement of the youth in the Methodist Church Ghana. The last but one section, the bedrock in which the whole topic is based emphatically contributes to the effects of change in the music of liturgy on the youth, while the writer concludes the last section of the article by discussing in detail the negative impact of the liturgical change in the music of the Methodist Church Ghana on the youth of today. -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

Anglican Church and the Development of Pentecostalism in Igboland

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 3 No. 10 ISSN 2240-0524 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2013 Anglican Church and the Development of Pentecostalism in Igboland Benjamin C.D. Diara Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka- Nigeria Nche George Christian Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka- Nigeria Doi:10.5901/jesr.2013.v3n10p43 Abstract The Anglican mission came into Igboland in the last half of the nineteenth century being the first Christian mission to come into Igboland, precisely in 1857, with Onitsha as the first spot of missionary propagation. From Onitsha the mission spread to other parts of Igboland. The process of the spread was no doubt, marked with the demonstration of the power of the Holy Spirit; hence the early CMS missionaries saw the task of evangelizing Igboland as something that could not have been possible without the victory of the Holy Spirit over the demonic forces that occupied Igboland by then. The objective of this paper is to historically investigate the claim that the presence of the Anglican Church in Igboland marked the origin of Pentecostalism among the Igbo. The method employed in this investigation was both analytical and descriptive. It was discovered that the Anglican mission introduced Pentecostalism into Igboland through their charismatic activities long before the churches that claim exclusive Pentecostalism came, about a century later. The only difference is that the original Anglican Pentecostalism was imbued in their Evangelical tradition as opposed to the modern Pentecostalism which is characterized by seemingly excessive emotional and ecstatic tendencies without much biblical anchorage. -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

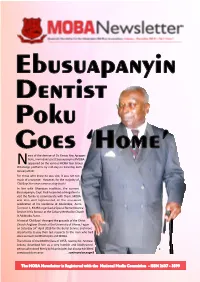

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc. -

SELECTION of HYMNS for SUNDAY CHURCH SERVICE in the METHODIST CHURCH GHANA: an EVALUATION Daniel S

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.3, No.11, pp.40-47, November 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) SELECTION OF HYMNS FOR SUNDAY CHURCH SERVICE IN THE METHODIST CHURCH GHANA: AN EVALUATION Daniel S. Ocran Department of Music Methodist University College Ghana, Dansoman Accra ABSTRACT: Methodism was born in song is an opening statement in the preface of the Methodist Hymn Book. Indeed the Methodists have not ceased to sing hymns in their worship since its establishment. Hymns that are sung for Sunday divine services have carefully been selected for several reasons. The paper evaluates the factors that motivate the selection of hymns in the Methodist Church, particularly for Sunday divine services. Through interviews of dedicated choirmasters and choristers as well as Reverend Ministers and local preachers, the authors present an assessment of the justifications behind selection of suitable hymns for church services. The authors argue that the paper will provide local preachers, pastors and reverend ministers an insight to selecting appropriate hymns for church services. KEYWORDS: Selection, Hymns, Methodist Church, Sunday divine services INTRODUCTION The Development of Christian Hymnody The Methodist Church Ghana is one of the early orthodox churches that were established by the European missionaries. In the early Christian church, the liturgy centred on a ritual commemorating the Last Supper of Jesus and his disciples as recounted in the New Testament (Matt.26: 30). The instituted pattern of worship at the time included singing of translated Western hymns, which favoured only the few educated elite. -

Mining Community Benefits in Ghana: a Case of Unrealized Potential

Mining Community Benefits in Ghana: A Case of Unrealized Potential Andy Hira and James Busumtwi-Sam, Simon Fraser University [email protected], [email protected], A project funded by the Canadian International Resources and Development Institute1 December 18, 2018 1 All opinions are those of the authors alone TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements List of Abbreviations Map of Ghana showing location of Mining Communities Map of Ghana showing major Gold Belts Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 1 Introduction ……………………………………………………………….... 4 1.1 Overview of the Study………………………………………………………… 4 1.2 Research Methods and Data Collection Activities …………………………… 5 Part 1 Political Economy of Mining in Ghana …………………………... 7 Chapter 2 Ghana’s Political Economy………………………………………………... 7 2.1 Society & Economy …………………………………………………………… 7 2.2 Modern History & Governance ……………………………………………….. 8 2.3 Governance in the Fourth Republic (1993-2018) ……………………………... 9 Chapter 3 Mining in Ghana ……………………………………………………………12 3.1 Overview of Mining in Ghana ……………………….……………………...... 13 3.2 Mining Governance…………………………………………………………… 13 3.3 The Mining Fiscal Regime …………………………………………………… 17 3.4 Distribution of Mining Revenues …………………………………………….. 18 Part 2 Literature Review: Issues in Mining Governance ……………... 21 Chapter 4 Monitoring and Evaluation of Community Benefit Agreements …… 21 4.1 Community Benefit Agreements (CBA) ……………………………………… 20 4.2 How Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) Can Help to Improve CBAs ……….. 29 Chapter 5 Key Governance Issues in Ghana’s Mining Sector ……………………. 34 5.1 Coherence in Mining Policies & Laws/Regulations …………………………... 34 5.2 Mining Revenue Collection …………………………………………………… 35 5.3 Distribution & Use of Mining Revenues ………………………………………. 36 5.4 Mining Governance Capacity ………………………………………………….. 37 5.5 Mining and Human Rights ……………………………………………………... 38 5.6 Artisanal & Small Scale Mining and Youth Employment ……………………...39 5.7 Other Key Issues: Women in Mining, Privatization of Public Services, Land Resettlement, Environmental Degradation …………………………………….