Stoke Field 1487

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aviation Classics Magazine

Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 taxies towards the camera in impressive style with a haze of hot exhaust fumes trailing behind it. Luigino Caliaro Contents 6 Delta delight! 8 Vulcan – the Roman god of fire and destruction! 10 Delta Design 12 Delta Aerodynamics 20 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan 62 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.6 Nos.1 and 2 64 RAF Scampton – The Vulcan Years 22 The ‘Baby Vulcans’ 70 Delta over the Ocean 26 The True Delta Ladies 72 Rolling! 32 Fifty years of ’558 74 Inside the Vulcan 40 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.3 78 XM594 delivery diary 42 Vulcan display 86 National Cold War Exhibition 49 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.4 88 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.7 52 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.5 90 The Council Skip! 53 Skybolt 94 Vulcan Furnace 54 From wood and fabric to the V-bomber 98 Virtues of the Avro Vulcan No.8 4 aviationclassics.co.uk Left: Avro Vulcan B2 XH558 caught in some atmospheric lighting. Cover: XH558 banked to starboard above the clouds. Both John M Dibbs/Plane Picture Company Editor: Jarrod Cotter [email protected] Publisher: Dan Savage Contributors: Gary R Brown, Rick Coney, Luigino Caliaro, Martyn Chorlton, Juanita Franzi, Howard Heeley, Robert Owen, François Prins, JA ‘Robby’ Robinson, Clive Rowley. Designers: Charlotte Pearson, Justin Blackamore Reprographics: Michael Baumber Production manager: Craig Lamb [email protected] Divisional advertising manager: Tracey Glover-Brown [email protected] Advertising sales executive: Jamie Moulson [email protected] 01507 529465 Magazine sales manager: -

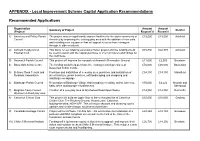

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations Recommended Applications Organisation Amount Amount Summary of Project District (Project) Request’d Recom’d 1) Annesley and Felley Parish The project aims to significantly improve facilities for the wider community of £19,500 £19,500 Ashfield Council Annesley by improving the existing play area with the addition of new units and installing new equipment that will appeal to users from teenagers through to older residents. 2) Ashfield Rugby Union This bid is for our 'Making Larwood a Home' project and the funding would £45,830 £22,915 Ashfield Football Club be used to assist with the capital purchase of internal fixtures and fittings for the clubhouse. 3) Awsworth Parish Council This project will improve the car park at Awsworth Recreation Ground. £11,000 £2,000 Broxtowe 4) Bassetlaw Action Centre The funding would help purchase the existing (rented) premises at £50,000 £20,000 Bassetlaw Bassetlaw Action Centre. 5) Bellamy Road Tenant and Provision and installation of new play area, purchase and installation of £34,150 £34,150 Mansfield Resident Association street furniture, picnic benches, soft landscaping and designing and installing new signage 6) Bilsthorpe Parish Council Restoration of Bilsthorpe Village Hall including re-roofing, toilets, kitchens, £50,000 £2,222 Newark and halls, office and storage refurbishment. Sherwood 7) Bingham Town Council Creation of a new play area at Wychwood Road Open Space. £14,950 £14,950 Rushcliffe Wychwood Road play area 8) Calverton Cricket Club This project will build an upper floor to the cricket pavilion at Calverton £35,000 £10,000 Gedling Cricket Club, The Rookery Ground, Woods Lane, Calverton, Nottinghamshire, NG14 6FF. -

Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England

ABSTRACT “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided by Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England Laura Christine Oliver, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D. This thesis argues that while patriarchy was certainly present in England during the late medieval period, women of the middle and upper classes were able to exercise agency to a certain degree through using both the patriarchal bargain and an economy of makeshifts. While the methods used by women differed due to the resources available to them, the agency afforded women by the patriarchal bargain and economy of makeshifts was not limited to the aristocracy. Using Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe as cases studies, this thesis examines how these women exercised at least a limited form of agency. Additionally, this thesis examines whether ordinary women have access to the same agency as elite women. Although both were exceptional women during this period, they still serve as ideal case studies because of the sources available about them and their status as role models among their contemporaries. “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided By Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England by Laura Christine Oliver, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Julie A. -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire Further electoral review December 2005 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Submissions received 23 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 25 Electorate figures 26 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 28 a Clipstone, Edwinstowe and Ollerton wards 29 b Bilsthorpe, Blidworth, Farnsfield and Rainworth wards 30 c Boughton, Caunton and Sutton-on-Trent wards 32 d Collingham & Meering, Muskham and Winthorpe wards 32 e Newark-on-Trent (five wards) 33 f Southwell town (three wards) 35 g Balderton North, Balderton West and Farndon wards 36 h Lowdham and Trent wards 38 Conclusions 39 Parish electoral arrangements 39 5 What happens next? 43 6 Mapping 45 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 47 B Code of practice on written consultation 51 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

Issues and Options Rushcliffe Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning

Rushcliffe Local Plan Rushcliffe Borough Council Rushcliffe Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies Issues and Options January 2016 Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Housing Development 6 3. Green Belt 31 4. Employment Provision and Economic Development 36 5. Regeneration 47 6. Retail Centres 49 7. Design and Landscape Character 55 8. Historic Environment 57 9. Climate Change, Flood Risk and Water Use 59 10. Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity 63 11. Culture, Tourism and Sports Facilities 69 12. Contamination and Pollution 72 13. Transport 75 14. Telecommunications Infrastructure 77 15. General 78 Appendices 79 Appendix A: Alterations to existing Green Belt ‘inset’ boundaries 80 Appendix B: Creation of new Green Belt ‘inset’ boundaries 89 Appendix C: District and Local Centres 97 Appendix D: Potential Centres of Neighbourhood Importance 105 i Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies Appendix E: Difference between Building Regulation and 110 Planning Systems Appendix F: Glossary 111 ii Local Plan Part 2: Land and Planning Policies 1. Introduction Rushcliffe Local Plan The Rushcliffe Local Plan will form the statutory development plan for the Borough. The Local Plan is being developed in two parts, the Part 1 – Core Strategy and the Part 2 – Land and Planning Policies (LAPP). The Council's aim is to produce a comprehensive planning framework to achieve sustainable development in the Borough. The Rushcliffe Local Plan is a ‘folder’ of planning documents. Its contents are illustrated by the diagram below, which also indicates the relationship between the various documents that make up the Local Plan. -

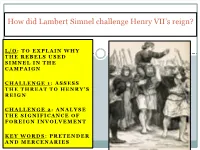

How Did Lambert Simnel Challenge Henry VII's Reign?

How did Lambert Simnel challenge Henry VII’s reign? L/O : TO EXPLAIN WHY THE REBELS USED SIMNEL IN THE CAMPAIGN CHALLENGE 1 : A S S E S S THE THREAT TO HENRY’S REIGN CHALLENGE 2 : A N A L Y S E THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT K E Y W O R D S : PRETENDER AND MERCENARIES First task-catch up on the background reading… https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/tudor- england/the-lambert-simnel-rebellion/ When you find someone you have not heard of, please take 5 minutes to Google them and jot down a few notes. Starting point… Helpful tip: Before you start to race through this slide, make sure that you know something about the Battle of Bosworth, the differences between Yorkists and Lancastrians and the story behind the Princes in the Tower. In the meantime - were the ‘Princes in the Tower’ still alive? Richard III and Henry VII both had the problem of these princely ‘threats’ but if they were dead who would be the next threat? Possibly, Edward, Earl of Warwick who had a claim to the throne What is a ‘pretender’ ? Royal descendant those throne is claimed and occupied by a rival, or has been abolished entirely. OR …an individual who impersonates an heir to the throne. The Role of Oxford priest Symonds was Lambert Simnel’s tutor Richard Symonds Yorkist Symonds thought Simnel looked like one of the Princes in the Tower Plotted to use him as a focus for rebellion – tutored him in ‘princely skills’ Instead, he changed his mind and decided to use him as an Earl of Warwick look-a-like Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy Sister of Edward IV and Richard -

Reservoirs of Hope Full Report

FULL PRACTITIONER ENQUIRY REPORT SPRING 2003 Reservoirs of Hope: Spiritual and moral leadership in headteachers How headteachers sustain their schools and themselves through spiritual and moral leadership based on hope. Alan Flintham, Headteacher, Quarrydale School, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire Contents Introduction 3 Summary of findings 6 Main findings: 8 1. The foundations of the reservoir: spiritual and moral bases of headship 8 2. Reservoirs of hope: towards a metaphor for spiritual and moral leadership 11 3. Replenishing the reservoirs: sustainability strategies in headship 15 4. Testing the reservoirs: the response to critical incidents 21 5. Developing the reservoirs: the growth of capacity 25 6. Building new reservoirs: the transference of capacity 29 Methodology 36 Acknowledgements 39 Bibliography 40 National College for School Leadership 2 Introduction The research concept “The starting point is not policy, it’s hope. Because from hope comes change” (Tony Blair, 2002) This research study seeks to test this statement against the leadership stories of 25 serving headteachers drawn from a cross-section of school contexts, phases and geographical locations within England. It is based on the premise that a school cannot move forward without a clear vision of where its leaders want it to reach. Without such a vision, clearly articulated, it remains static at best or at worst regresses, for ‘without vision the people perish’. ‘Hope’ is what drives the institution forward towards achieving its vision, whilst allowing it to remain true to its values whatever the external pressures. The successful headteacher, through acting as the wellspring of values and vision for the school thus acts as the external ‘reservoir of hope’ for the institution. -

Landowner Declaration Register

Landowner Declaration Register This is maintained under Section 31A of the Highways Act 1980 and Section 15B(1) of the Commons Act 2006. It comprises: Landowner deposit under S.15A(1) of the Commons Act 2006 By depositing a statement, landowners can prevent their land being registered as a Town or Village Green, provided they make the deposit before there has been 20 years recreational use of the land as of right. A new statement must be deposited within 20 years. Landowner deposit under S.31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 Highway statements and highway declarations allow landowners to prevent their land being recorded as a highway on the definitive map on the basis of presumed dedication (usually 20 years uninterrupted use). A highway statement or declaration must be followed by a further declaration within 20 years (or 10 years if lodged prior to 1 October 2013). Last Updated: September 2015 Ref Parish Landowner Details of land Highways Act 1980 CA1 Documents No. Section 31(6) 6 Date of Expiry date initial deposit A1 Alverton M P Langley The Belvedere, Alverton 17/07/2008 17/07/2018 A2 Annesley Multi owners Annesley Estate 30/03/1998 30/03/2004 expired A3 Annesley Notts Wildlife Trust Annesley Woodhouse Quarry 11/07/1997 13/01/2013 expired A4 Annesley Taylor Wimpey UK Little Oak Plantation 11/04/2012 11/04/2022 Ltd A5 Arnold Langridge Homes Ltd Lodge Farm, off Georgia Avenue 05/01/2009 05/01/2019 A6 Arnold Langridge Homes Ltd Land off Kenneth Road 05/01/2009 05/01/2019 A7 Arnold Langridge Homes Ltd Land off Calverton Road 05/11/2008 05/11/2018 -

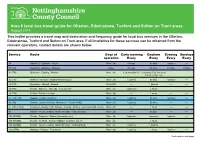

Area 6 Local Bus Travel Guide for Ollerton, Edwinstowe, Tuxford And

Area 6 local bus travel guide for Ollerton, Edwinstowe, Tuxford and Sutton on Trent areas August 2014 This leaflet provides a travel map and destination and frequency guide for local bus services in the Ollerton, Edwinstowe, Tuxford and Sutton on Trent area. Full timetables for these services can be obtained from the relevant operators, contact details are shown below. Service Route Days of Early morning Daytime Evening Sundays operation Every Every Every Every 14 Mansfield - Clipstone - Kirton Mon - Sat 60 mins 60 mins 1 journey ---- 15, 15A Mansfield - Clipstone - Walesby Daily 60 mins 60 mins 60 mins 60 mins 31 (TW) Bilsthorpe - Eakring - Ollerton Mon - Sat 1 journey (Mon-Fri) 3 journeys (Tue, Thur & Sat) ---- ---- 1 journey (Mon - Sat) 32 (TW) Ollerton - Kneesall - Newark (Phone a bus*) Mon - Sat 1 journey 60 mins 1 journey ---- 33 (TW) Egmanton - Norwell - Newark Wed & Fri ---- 1 journey ---- ---- 35 (TW) Retford - Elkesley - Walesby - New Ollerton Mon - Sat 2 journeys 2 hours ---- ---- 36 (TW) Retford - Tuxford - Laxton Mon - Sat ---- 2 hours ---- ---- 37, 37A, 37B Newark - Tuxford - Retford Mon - Sat 1 journey 60 mins 1 journey ---- 39, 39B Newark - Sutton-on-Trent - Normanton - (Tuxford 39B) Mon - Sat 1 journey 60 mins ---- ---- 41, 41B (CCVS) Fernwood - Barnby in the Willows - Newark - Bathley - (Cromwell 41B Sat only) Mon - Sat ---- 2 hours ---- ---- 95 Retford - South Leverton - North Wheatley - Gainsborough Mon - Sat ---- 60 mins ---- ---- 190 (GMMN) Retford - Rampton - Darlton (Commuter Link) Mon - Sat 2 journeys 2 journeys -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

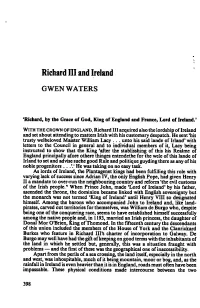

Richard III and Ireland GWEN WATERS ‘Richard, by the Grace of God, King of England and France, Lord of Ireland.’ WITH THE CROWN OF ENGLAND,Richard III acquired also the lordship of Ireland and set about attending to matters Irish with his customary despatch. He sent ‘his trusty welbeloved Maister William Lacy . unto his said lande of Irland’ with letters to the Council in general and to individual members of it, Lacy being instructed to show that the King ‘after the stablisshing of this his Realme of England principally afore othere thinges entendethe for the wele of this lands of Irland to set and advise suche good Rule and politique guyding there as any of his noble progenitors . .’.' He was taking on no easy task. As lords of Ireland, the Plantagenet kings had been fulfilling this role with varying lack of success since Adrian IV, the only English Pope, had given Henry II a mandate to over-run the neighbouring country and reform ‘the evil customs of the Irish people.” When Prince John, made ‘Lord of Ireland' by his father, ascended the throne, the dominion became linked with English sovereignty but the monarch was not termed ‘King of Ireland’ until Henry VIII so designated himself. Among the barons who accompanied John to Ireland and, like land- pirates, carved out territories for themselves, was William de Burgo who, despite being one of the conquering race, seems to have established himself successfully among the native people and, in 1193, married an Irish princess, the daughter of Donal Mor O'Brien, King of Thomond. -

5 Tudor Textbook for GCSE to a Level Transition

Introduction to this book The political context in 1485 England had experienced much political instability in the fifteenth century. The successful short reign of Henry V (1413-22) was followed by the disastrous rule of Henry VI. The shortcomings of his rule culminated in the s outbreak of the so-called Wars of the Roses in 1455 between the royal houses of Lancaster and York. England was then subjected to intermittent civil war for over thirty years and five violent changes of monarch. Table 1 Changes of monarch, 1422-85 Monarch* Reign The ending of the reign •S®^^^^^3^^!6y^':: -; Defeated in battle and overthrown by Edward, Earl of Henry VI(L] 1422-61 March who took the throne. s Overthrown by Warwick 'the Kingmaker' and forced 1461-70 Edward IV [Y] into exile. Murdered after the defeat of his forces in the Battle of Henry VI [L] 1470-?! Tewkesbury. His son and heir, Edward Prince of Wales, was also killed. Died suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving as his heir 1471-83 Edward IV [Y] the 13-year-old Edward V. Disappeared in the Tower of London and probably murdered, along with his brother Richard, on the orders of Edward V(Y] 1483 his uncle and protector, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who succeeded him on the throne. Defeated and killed at the Battle of Bosworth. Richard III [Y] 1483-85 Succeeded on the throne by his successful adversary Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. •t *(L]= Lancaster [Y)= York / Sence Brook RICHARD King Dick's Hole ao^_ 00/ g •%°^ '"^. 6'^ Atterton '°»•„>••0' 4<^ Bloody.