Resilient Communities the Case for Early Response Capacity Building Following Natural Disasters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Gippsland Floodplain Management Strategy 2018

WEST GIPPSLAND CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY West Gippsland Floodplain Management Strategy 2018 - 2027 Disclaimer Acknowledgements This publication may be of assistance to you but The development of this West Gippsland the West Gippsland Catchment Management Floodplain Management Strategy has involved Authority (WGCMA) and its employees do not the collective effort of a number of individuals guarantee that the publication is without flaw and organisations. of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your Primary author – Linda Tubnor (WGCMA) particular purpose. It therefore disclaims all Support and technical input – WGCMA liability for any error, loss or other consequence Board (Jane Hildebrant, Ian Gibson, Courtney which may arise from you relying on any Mraz), Martin Fuller (WGCMA), Adam Dunn information in this publication. (WGCMA), Catherine Couling (WGCMA), Copyright and representatives from VICSES, Bass Coast Shire Council, Baw Baw Shire Council, Latrobe © West Gippsland Catchment Management City Council, South Gippsland Shire Council, Authority Wellington Shire Council, East Gippsland First published 2017. This publication is Shire Council, East Gippsland Catchment copyright. No part may be reproduced by any Management Authority, DELWP, Bunurong process except in accordance with the provisions Land Council, Gunaikurnai Land and Waters of the Copyright Act 1968. Aboriginal Corporation and Boon Wurrung Foundation. Accessibility Acknowledgement of Country This document is available in alternative formats upon request. We would like to acknowledge and pay our respects to the Traditional Land Owners and other indigenous people within the catchment area: the Gunaikurnai, The Bunurong and Boon Wurrung, and the Wurundjeri people. We also recognise the contribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and organisations in Land and Natural Resource Management. -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Suburb 2008 Stateabbr Postcode Aberfeldy Vic 3825

SUBURB 2008 STATEABBR POSTCODE ABERFELDY VIC 3825 ADA VIC 3833 AGNES VIC 3962 AIRLY VIC 3851 ALBERTON VIC 3971 ALBERTON WEST VIC 3971 ALLAMBEE VIC 3823 ALLAMBEE RESERVE VIC 3871 ALLAMBEE SOUTH VIC 3871 AMOR VIC 3825 ARAWATA VIC 3951 ATHLONE VIC 3818 BAIRNSDALE VIC 3875 BALOOK VIC 3971 BAROMI VIC 3871 BAW BAW VIC 3833 BAW BAW VIC 3833 BAW BAW VILLAGE VIC 3833 BELLBIRD CREEK VIC 3889 BELLBIRD CREEK VIC 3889 BEMM RIVER VIC 3889 BENA VIC 3946 BENGWORDEN VIC 3875 BENNISON VIC 3960 BENNISON VIC 3960 BERRYS CREEK VIC 3953 BINGINWARRI VIC 3966 BINGINWARRI VIC 3966 BLACKWARRY VIC 3844 BOISDALE VIC 3860 BOISDALE VIC 3860 BONA VISTA VIC 3820 BOOLA VIC 3825 BOOLARONG VIC 3960 BOOLARRA VIC 3870 BOOLARRA SOUTH VIC 3870 BOOLE POOLE VIC 3880 BOOROOL VIC 3953 BRANDY CREEK VIC 3821 BRAVINGTON VIC 3821 BRIAGOLONG VIC 3860 BRIAGOLONG VIC 3860 BROADLANDS VIC 3875 BRUTHEN VIC 3885 BUCHAN VIC 3885 BUCHAN SOUTH VIC 3885 BUDGEREE VIC 3870 BUDGERUM EAST VIC 3579 BUFFALO VIC 3958 BUFFALO VIC 3958 BUFFALO RIVER VIC 3737 BUFFALO RIVER VIC 3737 BULDAH VIC 3890 BULLUMWAAL VIC 3875 BULN BULN VIC 3821 BULN BULN EAST VIC 3821 BUMBERRAH VIC 3902 BUNDALAGUAH VIC 3851 BUNYIP VIC 3815 BUNYIP NORTH VIC 3815 BUSHY PARK VIC 3860 BUTCHERS RIDGE VIC 3885 CABBAGE TREE CREEK VIC 3889 CABBAGE TREE CREEK VIC 3889 CALLIGNEE VIC 3844 CALLIGNEE NORTH VIC 3844 CALLIGNEE SOUTH VIC 3844 CALROSSIE VIC 3971 CALULU VIC 3875 CANN RIVER VIC 3890 CARINGAL VIC 3825 CARINGAL VIC 3825 CARRAJUNG VIC 3844 CARRAJUNG LOWER VIC 3844 CARRAJUNG SOUTH VIC 3844 CHANDLERS CREEK VIC 3890 CHILDERS VIC 3824 -

2012 Gippsland Flood Event - Review of Flood Warnings and Information Systems

2012 Gippsland Flood Event - Review of Flood Warnings and Information Systems TRIM ID: CD/12/522803 Date: 21 November 2012 Version: Final OFFICE of the EMERGENCY SERVICES COMMISSIONER Page i MINISTERIAL FOREWORD In early June this year, heavy rain and widespread flooding affected tens of thousands of Victorians across the central and eastern Gippsland region. The damage to towns and communities was widespread – particularly in the Latrobe City, Wellington and East Gippsland municipalities. Homes, properties and businesses were damaged, roads and bridges were closed, and more than 1500 farmers were impacted by the rains. A number of people were rescued after being trapped or stranded by the rising waters. Following the floods, some communities had a perception that telephone-based community warnings and information had failed them. As the Minister for Police and Emergency Services, I requested Victoria’s Emergency Services Commissioner to review the effectiveness, timeliness and relevance of the community information and warnings. This report has met my expectations and has identified the consequences and causes for the public’s perception. I welcome the review’s findings. I am confident these will, in time, lead to better and more effective arrangements for community information and warnings and contribute to a safer and more resilient Victoria. PETER RYAN Minister for Police and Emergency Services Page ii Contents Glossary ......................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 1 1. June 2012 Gippsland flood.................................................................................3 1.1 Key physical aspects of the 2012 Gippsland flood event 3 1.2 Key aspects of information and warnings in the incident response 6 1.2.1 Key information and warnings from Bureau of Meteorology 6 1.2.2 Key information and warnings through incident management 7 2. -

Port Information Handbook Gippsland Lakes

Gippsland Ports Port Information Handbook Part 2 Port of Gippsland Lakes Effective 27th July 2017 The Narrows at Lakes Entrance CONTENTS SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PREAMBLE .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Disclaimer ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 Datum ..................................................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Definitions .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.5.1 Agent ............................................................................................................................... 2 1.5.2 Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) ................................................................ 2 1.5.3 Berthed Vessel ................................................................................................................. 2 1.5.4 Bunkering Operations ...................................................................................................... 2 1.5.5 Cargo............................................................................................................................... -

Assessment of Victoria's Coastal Reserves Draft Report

Assessment of Victoria’s Coastal Reserves Draft Report For Public Comment October 2019 Victorian Environmental Assessment Council The Victorian Environmental Assessment Council (VEAC) was established in 2001 under the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council Act 2001. It provides the State Government of Victoria with independent advice on protection and management of the environment and natural resources of public land. The five Council members are: Ms Janine Haddow (Chairperson) Ms Joanne Duncan Ms Anna Kilborn Dr Charles Meredith Dr Geoffrey Wescott Acknowledgement of Aboriginal Victorians The Victorian Environmental Assessment Council pays its respects to Victoria’s Aboriginal peoples, Native Title Holders and Traditional Owners and acknowledges their rich cultural and intrinsic connections to Country. Council recognises that the land and sea is of spiritual, cultural, environmental and economic importance to Aboriginal people and values their contribution and interest in the management of land and sea. Written submissions are invited on this draft report. The closing date for submissions is Monday 11 November 2019. You may make an online submission via VEAC’s website at www. veac.vic.gov.au or send your written submission by post or by email (see contact details). There is no required format for submissions, except that you must provide your name, address and your contact details, including an email address if you have one. All submissions will be treated as public documents and will be published on VEAC’s website. Please contact VEAC if you do not wish your submission to be published. The name of each submitter will be identified as part of each published submission, but personal contact details will be removed before publishing. -

STFC Delivery Postcodes & Suburbs

STFC Delivery Postcodes ID Name Suburb Postcode 1 SYD METRO ABBOTSBURY 2176 1 SYD METRO ABBOTSFORD 2046 1 SYD METRO ACACIA GARDENS 2763 1 SYD METRO ALEXANDRIA 2015 1 SYD METRO ALEXANDRIA 2020 1 SYD METRO ALFORDS POINT 2234 1 SYD METRO ALLAMBIE HEIGHTS 2100 1 SYD METRO ALLAWAH 2218 1 SYD METRO ANNANDALE 2038 1 SYD METRO ARNCLIFFE 2205 1 SYD METRO ARNDELL PARK 2148 1 SYD METRO ARTARMON 2064 1 SYD METRO ASHBURY 2193 1 SYD METRO ASHCROFT 2168 1 SYD METRO ASHFIELD 2131 1 SYD METRO AUBURN 2144 1 SYD METRO AVALON BEACH 2107 1 SYD METRO BALGOWLAH 2093 1 SYD METRO BALGOWLAH HEIGHTS 2093 1 SYD METRO BALMAIN 2041 1 SYD METRO BALMAIN EAST 2041 1 SYD METRO BANGOR 2234 1 SYD METRO BANKSIA 2216 1 SYD METRO BANKSMEADOW 2019 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN 2200 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN AERODROME 2200 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN NORTH 2200 1 SYD METRO BANKSTOWN SQUARE 2200 1 SYD METRO BARANGAROO 2000 1 SYD METRO BARDEN RIDGE 2234 1 SYD METRO BARDWELL PARK 2207 1 SYD METRO BARDWELL VALLEY 2207 1 1 SYD METRO BASS HILL 2197 1 SYD METRO BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 1 SYD METRO BAYVIEW 2104 1 SYD METRO BEACON HILL 2100 1 SYD METRO BEACONSFIELD 2015 1 SYD METRO BEAUMONT HILLS 2155 1 SYD METRO BEECROFT 2119 1 SYD METRO BELFIELD 2191 1 SYD METRO BELLA VISTA 2153 1 SYD METRO BELLEVUE HILL 2023 1 SYD METRO BELMORE 2192 1 SYD METRO BELROSE 2085 1 SYD METRO BELROSE WEST 2085 1 SYD METRO BERALA 2141 1 SYD METRO BEVERLEY PARK 2217 1 SYD METRO BEVERLY HILLS 2209 1 SYD METRO BEXLEY 2207 1 SYD METRO BEXLEY NORTH 2207 1 SYD METRO BEXLEY SOUTH 2207 1 SYD METRO BIDWILL 2770 1 SYD METRO BILGOLA BEACH -

Victoria Government Gazette by Authority of Victorian Government Printer

Victoria Government Gazette By Authority of Victorian Government Printer No. G 30 Thursday 30 July 2020 www.gazette.vic.gov.au GENERAL 1454 G 30 30 July 2020 Victoria Government Gazette TABLE OF PROVISIONS Private Advertisements Still & Co. Lawyers 1461 State Aid to Religion Abolition Act 1871 – T. J. Mulvany & Co. 1461 The Presbyterian Church of Victoria 1455 TR Legal 1461 Dissolution of Partnership Tragear & Harris Lawyers 1461 Piazza Hairdressing for Men & Women 1456 Proclamations 1462 Estates of Deceased Persons Argent Law 1456 Government and Outer Budget Sector Agencies Notices 1463 Arthur J. Dines & Co. 1456 Aughtersons 1456 Orders in Council 1492 Beck Legal 1457 Crown Land (Reserves); Cornwalls 1457 Development Victoria; Education and Training Reform; Featherbys Lawyers 1457 Land; Hicks Oakley Chessell Williams 1457 Major Transport Projects Facilitation; Irlicht & Broberg Lawyers 1458 Public Health and Wellbeing Joliman Lawyers 1458 Obtainables 1502 KHQ Lawyers 1458 Kirby & Co. 1458 Lawson Hughes Peter Walsh 1458 Lobb & Kerr Lawyers 1458 Lorraine Jones & Associates 1459 Martin J. Hull Lawyer 1459 Maurice Blackburn Lawyers 1459 Michael Best 1460 Mills Oakley 1460 Moores 1460 Perpetual Legal Services Pty Ltd 1460 Ralph James Smith 1460 Advertisers Please Note As from 30 July 2020 The last Special Gazette was No. 378 dated 29 July 2020. The last Periodical Gazette was No. 1 dated 3 June 2020. How To Submit Copy • See our webpage www.gazette.vic.gov.au • or contact our office on 8523 4601 between 8.30 am and 5.30 pm Monday to Friday -

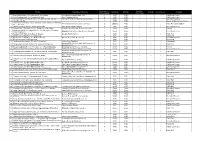

Facility Committee/Club/Group Hierarchy Level (Where Applied)

Hierarchy level Committee Facility Committee/Club/Group Ownership Manager Subsidy Lease/Licence Category (where applied) Club/Group 1 Community Garden, 17 Central Avenue, Loch Sport Loch Sport Community Garden Inc 4 WSC WSC √ √ Club/Group/Tenant 2 Airly-Clydebank Hall, 556 Clydebank Rd, Airly Airly-Clydebank Hall Inc. 4 WSC WSC √ √ Club/Group/Tenant 3 Alberton West Recreation Reserve, 331-333 Lanes Rd, Alberton Alberton West Recreation Reserve Committee 3 Crown Crown √ √ Recreation Reserve 4 Aqua Energy, Sale 1 WSC WSC Aquatic facility & Leisure Centre Avon Indoor Recreation Centre, Stratford Primary School, 12 Wellsford 5 Avon Indoor Recreation Centre Committee 2 DEECD WSC √ √ Indoor Recreation Stadium Street, Stratford 6 Baldwin Reserve, 305-321 Raglan Street, Sale Sale United Football Club Inc. 2 WSC WSC √ √ Recreation Reserve 7 Bellbird Corner Riverside Reserve, Sandy Creek Rd, Maffra Bellbird Corner Riverside Reserve Committee 4 Crown Crown √ √ Reserve Binginwarri Hall & Recreation Reserve, 675 Albert River-Welshpool 8 Binginwarri Hall & Recreation Reserve Committee 4 Crown Crown √ √ Recreation Reserve Road, Binginwarri 9 Boisdale Public Hall, 42-44 Main St, Boisdale Boisdale Public Hall Inc. 4 WSC WSC √ √ √ Public Hall 10 Boisdale Recreation Reserve Playground 4 WSC WSC Playground 11 Boisdale Recreation Reserve, Main St, Boisdale Boisdale Recreation Reserve Inc. 4 WSC WSC √ √ √ Recreation Reserve 12 Briagolong Anzac Park Playground 4 WSC WSC Playground 13 Briagolong Kindergarten, 28 Cahill St, Briagolong Uniting Care Gippsland 4 -

Growth Strategy

Growth Strategy Bairnsdale Volume 2 Background Analysis Building a Better Bairnsdale Prepared by CPG Australia Pty Ltd November 2009 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 The Regional Role and Context of Bairnsdale 2 3 Key Planning Policy Framework 7 3.1 The Bairnsdale Strategy Plan (1991) 7 3.2 Local Planning Policy Framework (LPPF) 8 4 Bairnsdale’s Demographic Profile 9 4.1 Population 9 4.2 Age structure 9 4.3 Dwelling type and structure 11 4.4 Employment 11 4.5 Summary 13 5 Bairnsdale’s Land Supply Profile 14 5.1 Settlement patterns 14 5.2 Overall land supply (rural and urban zoned land) 15 5.3 Current development activity 18 5.4 Residential development potential 18 5.4.1 Standard residential density 19 5.4.2 Low density residential 20 5.4.3 Rural living 21 5.5 Industrial / commercial development potential 24 5.5.1 Industrial land supply 24 5.5.2 Business land supply 24 5.6 Opportunities and constraints 25 6 Economic Development 28 6.1 Employment profile 28 6.1.1 Key findings 28 6.1.2 Unemployment trends 29 6.1.3 Threats to the economy 29 6.1.4 Retail catchment 32 6.2 Opportunities and constraints 37 7 Bairnsdale Activity Centre 39 7.1 Existing conditions 39 7.2 Land use, structure and boundaries 39 CPG Australia Pty Ltd (Formerly Coomes Consulting Group) ABN 55 050 029 635 A subsidiary of Downer EDI Limited 24 Albert Road PO Box 305 South Melbourne Victoria 3205 Australia T 03 9993 7888 F 03 9993 7999 cpg-global.com 7.2.1 Overview 39 7.2.2 Challenges to the structure and role of the CBD 40 7.2.3 Recreation and entertainment 41 7.2.4 Housing -

The Gippsland Lakes Important Bird and Biodiversity Area Monitoring Project: a Report on the First Five Years 2011 - 2015

THE GIPPSLAND LAKES IMPORTANT BIRD AND BIODIVERSITY AREA MONITORING PROJECT: A REPORT ON THE FIRST FIVE YEARS 2011 - 2015 Photos: Top, Gippsland Lakes, Brian Martin Above left, Black Swan, Ken Sherring Above, Chestnut Teal, Chris Healey Left, Musk Duck, (C) Ian Wilson 2016 birdlifephotography.org.au 1 Prepared by Chris Healey on behalf of BirdLife East Gippsland Published by BirdLife East Gippsland PO Box 825 Bairnsdale Victoria 3875 April 2017 Acknowledgements The contribution of many members of BirdLife East Gippsland to the ongoing survey effort on which this report is based is gratefully acknowledged. Special thanks are due to members of the GLIBA review panel for their participation in the review process, and especially to Dr Lucas Bluff, Senior Biodiversity Office, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Bairnsdale for advice on project design, evaluation and interpretation of data. Thanks are also due to landholders who allowed members of survey teams to access their properties to undertake surveys. BirdLife East Gippsland is a regional branch of BirdLife Australia, promoting the appreciation, understanding and conservation of birds and their habitats. The BirdLife East Gippsland region covers the East Gippsland and Wellington Shires in Victoria’s east, and includes some of the state’s most magnificent wilderness areas. It encompasses the extensive waterways of the Gippsland Lakes, 90 Mile Beach, the iconic Snowy River region, extensive old-growth forests, alpine meadows and the last free-flowing wild rivers of southeast Australia. 2 THE GIPPSLAND LAKES IMPORTANT BIRD AND BIODIVERSITY AREA MONITORING PROJECT: A REPORT ON THE FIRST FIVE YEARS 2011 - 2015 INTRODUCTION: The BirdLife East Gippsland ‘Gippsland Lakes Important Bird and Biodiversity Area Monitoring Project’ (GLIBA Project) commenced in the latter part of 2011 in response to a call by the then Bird Observation and Conservation Australia for regional branches to ‘adopt’ a local IBA (Important Bird and Biodiversity Area). -

2. Marine & Coastal Ecosystems

2. Marine & Coastal Ecosystems 26 MARINE AND COASTAL ECOSYSTEMS Guide to chapter 2 This chapter focuses on marine and coastal environments in recognition of their tight ecological links and the need for integrated management. The area of focus is waters under the jurisdiction of the Victorian government, which extend 5.5 kilometres seaward from the high water mark, and land within 500 metres of the shoreline. Some issues relevant to the coast are covered in chapters 3 and 4 on terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems. Section 2.1 describes the high natural, social and economic values of Victoria’s marine and coastal ecosystems and the major habitat types. Section 2.2 outlines the status of biodiversity and protected areas, and the condition of bays, inlets and estuaries. Major threats to marine and coastal nature – particularly climate change, coastal development, invasive species and fishing – are described in section 2.3. Section 2.4 is a summary of a gap analysis of Victoria’s marine protected areas, which identifies bioregional priorities for new and expanded marine national parks and sanctuaries. Similarly, for coastal subregions, section 2.5 summarises an analysis of values, threats and priorities for upgrading the national park and conservation system. Finally, in sections 2.6 and 2.7, policy gaps and high priority reforms are identified in three major areas: improving knowledge, creating a comprehensive, adequate and representative national park and conservation system, and integrating and strengthening management of marine and coastal