Judicial Review Before Marbury 58 Stan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emerging Genre of the Constitution: Kent Newmyer and the Heroic Age

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2021 The Emerging Genre of The Constitution: Kent Newmyer and the Heroic Age Mary Sarah Bilder Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Bilder, Mary Sarah, "The Emerging Genre of The Constitution: Kent Newmyer and the Heroic Age" (2021). Connecticut Law Review. 459. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/459 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 52 FEBRUARY 2021 NUMBER 4 Essay The Emerging Genre of The Constitution: Kent Newmyer and the Heroic Age MARY SARAH BILDER In written celebration of Kent Newmyer’s intellectual and collegial influence, this Essay argues that the written constitution was an emerging genre in 1787-1789. Discussions of the Constitution and constitutional interpretation often rest on a set of assumptions about the Constitution that arose in the years and decades after the Constitutional Convention. The most significant one involves the belief that a fixed written document was drafted in 1787 intended in our modern sense as A Constitution. This fundamental assumption is historically inaccurate. The following reflections of a constitutionalist first lay out the argument for considering the Constitution as an emerging genre and then turn to Kent Newmyer’s important influence. The Essay argues that the constitution as a system or frame of government and the instrument were not quite one and the same. This distinction helps to make sense of ten puzzling aspects of the framing era. 1263 The Emerging Genre of The Constitution: Kent Newmyer and the Heroic Age MARY SARAH BILDER * In written celebration of Kent Newmyer’s intellectual and collegial influence, this Essay argues that the written constitution was an emerging genre in 1787-1789. -

The Shape of the Electoral College

No. 20-366 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., Appellants, v. STATE OF NEW YORK, ET AL., Appellees. On Appeal From the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE MICHAEL L. ROSIN IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES PETER K. STRIS MICHAEL N. DONOFRIO Counsel of Record BRIDGET C. ASAY ELIZABETH R. BRANNEN STRIS & MAHER LLP 777 S. Figueroa St., Ste. 3850 Los Angeles, CA 90017 (213) 995-6800 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................... i INTEREST OF AMICUS .................................................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .......................................... 2 ARGUMENT ....................................................................... 4 I. Congress Intended The Apportionment Basis To Include All Persons In Each State, Including Undocumented Persons. ..................... 4 A. The Historical Context: Congress Began to Grapple with Post-Abolition Apportionment. ............................................... 5 B. The Thirty-Ninth Congress Considered—And Rejected—Language That Would Have Limited The Basis of Apportionment To Voters or Citizens. ......... 9 1. Competing Approaches Emerged Early In The Thirty-Ninth Congress. .................................................. 9 2. The Joint Committee On Reconstruction Proposed A Penalty-Based Approach. ..................... 12 3. The House Approved The Joint Committee’s Penalty-Based -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

Keep Reading Wilson As a Justice

Wilson as a Justice MAEVA MARCUS* ABSTRACT James Wilson, a founding father of great intellect and promise, never ful®lled his potential as a Justice. This paper explores his experience on the Supreme Court and the reasons that led to his failure to achieve the distinction that was expected of him. James Wilson very much wanted to be the ®rst Chief Justice.1 But when George Washington denied him that honor and nominated him to be an Associate Justice, he accepted and threw himself into the work with characteristic industry.2 Other than a title and $500 more in annual salary3 (Wilson probably wanted this more than anything else), Wilson lost little. Life as an Associate Justice would be no different from life as the Chief. A Justice occupied one of the most exalted positions in the new government and was paid more than any other federal em- ployee, except the President and the Vice-President.4 Nominations were the sub- ject of ®erce competition.5 But in 1789 no one knew exactly what that job would entail. This paper gives the reader some idea of what a Justice, and speci®cally James Wilson, did in the 1790s.6 Wilson spent more of his time on the bench of circuit courts than he did on the Supreme Court bench; thus, this paper will focus signi®- cantly on his circuit court activities.7 And Wilson performed his circuit court * Currently Director of the Institute for Constitutional History at the New-York Historical Society and Research Professor at the George Washington University Law School and General Editor of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States, Maeva Marcus previously edited The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800, an eight-volume series completed in 2006. -

1 Different Models for Protection of Constitutionality, Legality And

Prof. Tanja Karakamisheva-Jovanovska, Ph.D 1 Different Models for Protection of Constitutionality, Legality and Independence of Constitutional Court of the Republic of Macedonia 1. About the different models of protection of constitutionality and legality The Constitutional Court is a separate body that serves as a watchdog of the constitution in a given country, and as a protector of the constitutionality, legality, and the citizens' freedoms and rights within the national legal system. From an organisational point of view, there are several models of constitutionality that can be determined, as follows: 1. American model based on the Marbery vs. Madison case (Marbery vs. Madison, 1803) , and, in accordance with the John Marshal doctrine, according to whom the constitutional issues are subject of interest and resolution of all courts that are under the scope of the regular judiciary (in an environment of decentralised, widespread of dispersed control procedure), and based on organisational procedure that is typical for the regular judiciary (incidenter). And while the American model with widespread system of protection of constitutionality gives the authority to all courts to assess the constitutionality of the laws, the European model concentrates all the power for the assessment of the constitutionality on one body. In Europe, there are number of countries that have accepted the American model, such as Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, and in North America, besides the U.S., this model is also applied in Canada, as well as, on the African continent, in Botswana, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya and other countries. 2 1 Associate Professor for Constitutional Law and Political System at the University "Sc. -

The Constitutionality of Statutes of Repose: Federalism Reigns

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 38 Issue 3 Issue 3 - April 1985 Article 8 4-1985 The Constitutionality of Statutes of Repose: Federalism Reigns Josephine H. Hicks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Josephine H. Hicks, The Constitutionality of Statutes of Repose: Federalism Reigns, 38 Vanderbilt Law Review 627 (1985) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol38/iss3/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Constitutionality of Statutes of Repose: Federalism Reigns I. INTRODUCTION ...................................... 627 II. STATUTES OF REPOSE ............................. 628 A. Defining "Statute of Repose" ............... 628 B. Arguments For and Against Statutes of Re- p ose ...................................... 632 III. CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUES .............................. 635 A. Equal Protection .......................... 635 B. Due Process ............................... 642 C. Open Courts, Access to Courts, and Remedy. 644 IV. ANALYSIS .......................................... 648 A. Effect of State Constitutional Law .......... 648 B. Future Direction .......................... 652 C. Arguments For and Against National Legisla- tion ..................................... -

John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: a Reappraisal.”

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal.” Author: Arthur Scherr Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 1, Winter 2018, pp. 114-159. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 114 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2018 John Adams Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1815 115 John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal ARTHUR SCHERR Editor's Introduction: The history of religious freedom in Massachusetts is long and contentious. In 1833, Massachusetts was the last state in the nation to “disestablish” taxation and state support for churches.1 What, if any, impact did John Adams have on this process of liberalization? What were Adams’ views on religious freedom and how did they change over time? In this intriguing article Dr. Arthur Scherr traces the evolution, or lack thereof, in Adams’ views on religious freedom from the writing of the original 1780 Massachusetts Constitution to its revision in 1820. He carefully examines contradictory primary and secondary sources and seeks to set the record straight, arguing that there are many unsupported myths and misconceptions about Adams’ role at the 1820 convention. -

The Federal Constitution and Massachusetts Ratification : A

, 11l""t,... \e ,--.· ', Ir \" ,:> � c.'�. ,., Go'.l[f"r•r•r-,,y 'i!i • h,. I. ,...,,"'P�r"'T'" ""J> \S'o ·� � C ..., ,' l v'I THE FEDERAL CONSTlTUTlON \\j\'\ .. '-1',. ANV /JASSACHUSETTS RATlFlCATlON \\r,-,\\5v -------------------------------------- . > .i . JUN 9 � 1988 V) \'\..J•, ''"'•• . ,-· �. J ,,.._..)i.�v\,\ ·::- (;J)''J -�·. '-,;I\ . � '" - V'-'� -- - V) A TEACHING KIT PREPAREV BY � -r THE COIJMOMVEALTH M,(SEUM ANV THE /JASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES AT COLUM.BIA POINf ]') � ' I � Re6outee Matetial6 6ot Edueatot6 and {I · -f\ 066ieial& 6ot the Bieentennial 06 the v-1 U.S. Con&titution, with an empha6i& on Ma&&aehu&ett6 Rati6ieation, eontaining: -- *Ma66aehu6ett& Timeline *Atehival Voeument6 on Ma&&aehu&ett& Rati6ieation Convention 1. Govetnot Haneoek'6 Me&6age. �����4Y:t4���� 2. Genetal Coutt Re6olve& te C.U-- · .....1. *. Choo6ing Velegate& 6ot I\) Rati6ieation Convention. 0- 0) 3. Town6 &end Velegate Name&. 0) C 4. Li6t 06 Velegate& by County. CJ) 0 CJ> c.u-- l> S. Haneoek Eleeted Pte6ident. --..J s:: 6. Lettet 6tom Elbtidge Getty. � _:r 7. Chatge6 06 Velegate Btibety. --..J C/)::0 . ' & & • o- 8 Hane oe k Pt op o 6e d Amen dme nt CX) - -j � 9. Final Vote on Con&titution --- and Ptopo6ed Amenwnent6. Published by the --..J-=--- * *Clue6 to Loeal Hi&toty Officeof the Massachusetts Secretary of State *Teaehing Matetial6 Michaelj, Connolly, Secretary 9/17/87 < COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS !f1Rl!j OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE CONSTITUTtON Michael J. Connolly, Secretary The Commonwealth Museum and the Massachusetts Columbia Point RATIFICATION OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION MASSACHUSETTS TIME LINE 1778 Constitution establishing the "State of �assachusetts Bay" is overwhelmingly rejected by the voters, in part because it lacks a bill of rights. -

Badges of Slavery : the Struggle Between Civil Rights and Federalism During Reconstruction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction. Vanessa Hahn Lierley 1981- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lierley, Vanessa Hahn 1981-, "Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 831. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/831 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Liedey B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2013 BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Lierley B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Approved on April 19, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Benjamin Harrison Jasmine Farrier ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband Pete Lierley who always showed me support throughout the pursuit of my Master's degree. -

Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: a Context-Specific Analysis

Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design Volume 5 Article 1 4-13-2020 Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: A Context-Specific Analysis Samantha Lalisan Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijcd Part of the Common Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Conflict of Laws Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Lalisan, Samantha (2020) "Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: A Context-Specific Analysis," Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design: Vol. 5 , Article 1. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijcd/vol5/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Constitutional Design by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classifying Systems of Constitutional Review: A Context-Specific Analysis SAMANTHA LALISAN* “Access to the court is perhaps the most important ingredient in judicial power, because a party seeking to utilize judicial review as political insurance will only be able to do so if it can bring a case to court.”1 INTRODUCTION Europe’s experience with democratically elected fascist regimes leading to World War II is perhaps one of the most important developments for the establishment of new constitutional democracies. Post-war constitutional drafters sought to establish fundamental constitutional rights and to protect those rights through specialized constitutional courts.2 Many of these new democracies entrenched first-, second-, and third-generation rights into the constitution and included provisions to allow individuals access, direct or indirect, to the constitutional court to protect their rights through adjudication. -

Constitutional Tipping Points: Civil Rights, Social Change, and Fact-Based Adjudication

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2006 Constitutional Tipping Points: Civil Rights, Social Change, and Fact-Based Adjudication Suzanne B. Goldberg Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Suzanne B. Goldberg, Constitutional Tipping Points: Civil Rights, Social Change, and Fact-Based Adjudication, 106 COLUM. L. REV 1955 (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/65 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW VOL. 106 DECEMBER 2006 NO. 8 ARTICLES CONSTITUTIONAL TIPPING POINTS: CIVIL RIGHTS, SOCIAL CHANGE, AND FACT-BASED ADJUDICATION Suzanne B. Goldberg* This Article offers an account of how courts respond to social change, with a specific focus on the process by which courts "tip" from one under- standing of a social group and its constitutional claims to another. Adjudi- cation of equal protection and due process claims, in particular,requires courts to make normative judgments regarding the effect of traits such as race, sex, sexual orientation, or mental retardationon group members' status and capacity. Yet, Professor Goldberg argues, courts commonly approach decisionmaking by focusing only on the 'facts" about a social group, an approach that she terms 'fact-based adjudication." Professor Goldberg criti- ques this approachfor its flawed premise that restrictions on social groups can be evaluated based on facts alone and its role in obscuring judicial involvement in selecting among competing norms. -

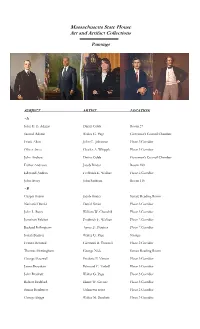

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C.