Antennae Issue 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Green Biography

STEPHEN GREEN BIOGRAPHY With over fifteen years in music Stephen Green has had experience in many different facets of the industry. From syndicated music columnist, marketing manager, radio reporter, inflight entertainment producer, street press journalist, vocalist, music retailer, voice-over artist and event manager, Stephen had a huge range of experiences before starting PR and marketing company Australian Music Biz in 1999. The business was formed to focus on allowing independent artists and labels to have media representation that could compete with more established record labels. He developed the company over seven years growing to support four staff. Clients included SonyBMG, EMI, Warner, Roadrunner, Rajon, Modern Music and many more. Over the years, the company has worked with the likes of The Butterfly Effect, Tom Jones, Kate Miller-Heidke, Hanson, Screaming Jets, Small Mercies, Epicure, The Red Paintings, The Boat People, Bodyjar and many more. In 2007, Stephen started his second company, Outbreak Marketing which dealt with internet and street marketing. Later that year, he sold his interests in both Australian Music Biz and Outbreak Marketing. Over the last two years he has split his time between two jobs, working as Program Director at Q Music (Queensland's music industry peak body) and radio project manager at digital media servicing company D-Star. His role at D-Star has seen him responsible for the rollout of Play MPE, a web-based tool for servicing tracks from record companies to radio stations in Australia, while his work with Q Music saw him programming and co-ordinating BIG SOUND in 2007 and 2008, which has quickly become Australia's most respected music business conference in Brisbane. -

Gagosian Gallery

Artforum January, 2000 GAGOSIAN 1999 Carnegie International Carnegie Museum of Art Katy Siegel When you walk into the lobby of the Carnegie Museum, the program of this year’s International announces itself in microcosm. There in front of you is atmospheric video projection (Diana Thater), a deadpan disquisition on the nature of representation (Gregor Schneider’s replication of his home), a labor-intensive, intricate installation (Suchan Kinoshita), a bluntly phenomenological sculpture (Olafur Eliasson), and flat, icy painting (Alex Katz). Undoubtedly the best part of the show, the lobby is also an archi-tectural site of hesitation, a threshold. Here the installation encapsulates the exhi-bition’s sense of historical suspen-sion, another kind of hesitation. Ours is a time not of endings but of pause. My favorite work, viewed through the museum’s huge glass wall, was the Eliasson, a fountain of steam wafting vertically from an expanse of water on a platform through which trees also rise up. It’s a heart-throbbing romantic landscape. Romantic, but not naive: The work plays on the tradition of the courtyard fountain, and the steam is piped from the museum’s heating system. Combining the natural and the industrial in a way peculiarly appro-priate to Pittsburgh on a quiet Sunday morning in early autumn, it echoed two billows of steam (or, more queasily, smoke?) off in the distance. When blunt physical fact achieves this kind of lyricism, it is something to see. Upstairs in the galleries, Ernesto Neto’s Nude Plasmic, 1999, relies as well on the phenomenology of simple form, but the Brazilian artist avoids Eliasson’s picturesque imagery. -

International Delegates International Delegates

15th – 17th October 2015 International delegates International delegates 3 Brandon Young Sync ACTIVISION BLIZZARD DIRECTOR, MUSIC AFFAIRS Andrea von Foerster USA FIRESTARTER MUSIC MUSIC SUPERVISOR Activision Publishing, Inc. is a leading worldwide developer, USA publisher and distributor of interactive entertainment and leisure products. Andrea von Foerster is a music supervisor for film, television and As the head of music for Activision Publishing, Inc., Brandon Young online projects based in Los Angeles. Throughout her extended has been an integral part of each brands music direction and inte- time in the industry, her credits include independent films such as gration for the company for over 10 years, and has spent a great (500) Days Of Summer, From Prada To Nada, Bellflower, and Begin deal of time managing relationships and partnerships with top in- Again; studio films such as Journey 2: The Mysterious Island, Chron- dustry artists ranging from Aerosmith, Van Halen, and Metallica, to icle, Chasing Mavericks, Devil’s Due, and Fantastic Four; music doc- pop-country superstar Taylor Swift, to Jay-Z and Eminem among umentaries such as The White Stripes Under Great White Northern many others. In addition to this he and his team have been Lights and Butch Walker: Out Of Focus. Her television work includes responsible for licensing over 3,000 songs on more than 130 titles Dollhouse, Stargate Universe, Don’t Trust the B in Apt. 23 and nu- in his tenure with the company. Activision Publishing, Inc. is one merous MTV shows such as Run’s House -

Gagosian Gallery

Hyperallergic February 13, 2019 GAGOSIAN Portraits that Feel Like Chance Encounters and Hazy Recollections Nathaniel Quinn’s first museum solo show features work which suggests that reality might best be recognized by its disjunctions rather than by single-point perspective. Debra Brehmer Nathaniel Mary Quinn, “Bring Yo’ Big Teeth Ass Here!” (2017) (all images courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman gallery) Nathaniel Mary Quinn is one of the best portrait painters working today and the competition is steep. Think of Amy Sherald, Elizabeth Peyton, Kehinde Wiley, Nicole Eisenman, Allison Schulnik, Mickalene Thomas, Jeff Sonhouse, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Chris Ofili, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Lynette Yiadom- Boakye to name a few. It could be argued that these artists are not exclusively portrait artists but artists who work with the figure. The line blurs. If identity, memory, and personality enter the pictorial conversation, however, then the work tips toward portraiture — meaning it addresses notions of likeness in relation to a real or metaphorical being. No longer bound by functionality or finesse, contemporary artists are revisiting and revitalizing the portrait as a signifier of presence via a reservoir of constructed, culturally influenced identities. The outsize number of black artists now working in the portrait genre awakens the art world with vital new means of representation. It makes sense that artists who have been kept on the margins of the mainstream art world for centuries might emerge with the idea of visibility front and center. Without a definitive canonical art history of Black self-representation, there are fewer conventions for the work to adhere to. -

Download PDF Title Sheet

New title information Dimensions Variable Product Details New Works for the British Council Collection £15 Artist(s) Fiona Banner, Don Brown, Angela Bulloch, Mat Collishaw, Martin Creed, artists: Fiona Banner, Don Brown & Stephen Murphy, Angela Bulloch, Willie Doherty, Angus Fairhurst, Ceal Floyer, Douglas Gordon, Graham Mat Collishaw, Martin Creed, Willie Doherty, Angus Fairhurst, Ceal Gussin, Mona Hatoum, Damien Hirst, Floyer, Douglas Gordon, Graham Gussin, Mona Hatoum, Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Michael Landy, Stephen Gary Hume, Michael Landy, Chris Ofili, Simon Patterson, Vong Murphy, Chris Ofili, Simon Patterson, Phaophanit, Georgina Starr, Sam Taylor-Wood, Mark Wallinger, Gillian Vong Phaophanit, Georgina Starr, Wearing, Rachel Whiteread, Catherine Yass Sam Taylor-Wood, Mark Wallinger, Gillian Wearing, Rachel Whiteread, Catherine Yass The title of this book and the choice of George Stubbs’s painting of a zebra on its cover points to one of the underlying preoccupations of the Publisher British Council artists selected: the constantly shifting perspectives that new ISBN 9780863553769 information, new technologies and new circumstances make evident. Format softback Dimensions Variable features recent purchases for the British Council Pages 112 Collection of works by a generation of artists who have come to Illustrations over 100 colour and 9 b&w prominence in the last decade. The works, each illustrated in full colour, illustrations represent a variety of approaches, concerns and means of realisation. Dimensions 295mm x 230mm Weight 700 The influence of past movements in 20th Century art – particularly Conceptualism, but also Minimalism, Performance and Pop Art – are readily discerned in much of the work. Young British artists have received a great deal of attention in the past few years and have often been perceived as a coherent national grouping. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture PLANTAE, ANIMALIA, FUNGI: TRANSFORMATIONS OF NATURAL HISTORY IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN ART A Dissertation in Art History by Alissa Walls Mazow © 2009 Alissa Walls Mazow Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 The Dissertation of Alissa Walls Mazow was reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Brian A. Curran Associate Professor of Art History Richard M. Doyle Professor of English, Science, Technology and Society, and Information Science and Technology Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation examines the ways that five contemporary artists—Mark Dion (b. 1961), Fred Tomaselli (b. 1956), Walton Ford (b. 1960), Roxy Paine (b. 1966) and Cy Twombly (b. 1928)—have adopted the visual traditions and theoretical formulations of historical natural history to explore longstanding relationships between “nature” and “culture” and begin new dialogues about emerging paradigms, wherein plants, animals and fungi engage in ecologically-conscious dialogues. Using motifs such as curiosity cabinets and systems of taxonomy, these artists demonstrate a growing interest in the paradigms of natural history. For these practitioners natural history operates within the realm of history, memory and mythology, inspiring them to make works that examine a scientific paradigm long thought to be obsolete. This study, which itself takes on the form of a curiosity cabinet, identifies three points of consonance among these artists. -

Wolverhampton Arts & Culture

WOLVERHAMPTON ARTS & CULTURE STELLAR: STARS OF OUR CONTEMPORARY COLLECTION LEARNING PACK Allen Jones, Dream T-Shirt, 1964. © the artist TAKE LEARNING OUT OF THE CLASSROOM Wolverhampton Arts and Culture venues are special places where everyone can enjoy learning and develop a range of skills. Learning outside the classroom in museums, galleries and archives gives young people the confidence to explore their surroundings and broadens their understanding of people and the world around them. Contents Page 2 What is Contemporary Art - Page 14 Viewing and Reading or ‘When’? Page 15 Bibliography Page 4 Modern or Contemporary? Page 15 How to get in touch Page 12 Form or Idea? Stellar: Stars of our Contemporary Collection Stellar presents an overview of recent, or are by artists nominated for the Turner current and ongoing developments in Prize, which from 1984 has been awarded British art, as viewed through the lens of annually to the artist who has achieved an Wolverhampton Art Gallery’s collection. outstanding exhibition or presentation of Many of the works included in this their work. Accordingly, Stellar charts the exhibition also featured in past iterations changing face and shifting landscape of of the prestigious British Art Show – contemporary art practice in the United a touring exhibition that celebrates the Kingdom. Stellar is presented ahead of country’s most exciting contemporary art – British Art Show 9, which opens in Wolverhampton in March 2021. Unlike other art forms, contemporary practice can be an elusive topic to describe; there is no readymade definition and a walk through Stellar clearly reveals a wide variety of styles and techniques. -

A Journal of the Radical Gothic

issue #1 gracelessa journal of the radical gothic And the ground we walk is sacred And every object lives And every word we speak Will punish or forgive And the light inside your body Will shine through history Set fire to every prison Set every dead man free “The Sound Of Freedom” Swans cover photograph by Holger Karas GRACELESS Issue one, published in February 2011 Contributors and Editors: Libby Bulloff (www.exoskeletoncabaret. com), Kathleen Chausse, Jenly, Enola Dismay, Johann Elser, Holger Karas (www. seventh-sin.de), Margaret Killjoy (www. birdsbeforethestorm.net). Graceless can be contacted at: www.graceless.info [email protected] This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to: Creative Commons 171 Second Street, Suite 300 San Francisco, California, 94105 USA What this license means is that you are free (and encouraged) to take any content from Graceless and re-use it in part or whole, or make your own work that incorporates ours, as long as you: attribute the creator of the work, share the work with the same license, and are using the product non-commercially. Note that there is a photograph that is marked as copyright to its creator, which was used with permission and may not be included in derivative works. We have chosen a Creative Commons licensing because we believe in free cultural exchange but intend to limit the power of capitalism to co-opt our work for its twisted ends. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Rave Magazine - Brisbane Street Press - the FALL – Ersatz GB

Rave Magazine - Brisbane Street Press - THE FALL – Ersatz GB http://www.ravemagazine.com.au/content/view/30478/180/ Welcome to ravemagazine.com.au the search... on-line home of Brisbane's leading street magazine - now with daily site updates to keep you in touch with all the latest music news, tour and gig information. HOME NEWS & REVIEWS GIGS CLASSIFIEDS WIN STUFF ADVERTISING CONTACT US LOGIN / OUT Publish your press releases, gig listings, classified ads and more.... all for FREE! Click here for details. THE FALL – Ersatz GB MONDAY, 05 DECEMBER 2011 (Cherry Red/Fuse) Manc legends’ 29th LP offers more of the same On this side of the globe, The Fall remain the band music fans “in the know” tend to admire, but few others seem to care about. Long one of England’s most acerbic lyricists and a markedly singular vocalist, Mark E Smith has sneered, grumbled and snarled his way through nearly three-and-a-half decades, and on Ersatz GB – the Mancunians’ album number 29 – he resembles a disgruntled pensioner with a cold. Recorded between London and Berlin, the LP features the same established line-up that provided the instrumentation for 2008’s Imperial Wax Solvent and 2010’s Your Future Our Clutter. Sonically, it’s probably The Fall’s heaviest-sounding record to date, with rockers like Greenway and sinister, eight-minute Monocard respectively driven by cod-alt-metal and cod-drone-rock guitar riffs. As expected, Smith’s Get Rave delivered FREE to your non-voice and semi-intelligible diatribes are still very much an acquired inbox every Tuesday. -

Cinematic Visions Painting at the Edge of Reality

Victoria Miro Cinematic Visions Painting at the Edge of Reality An exhibition in support of the Bottletop Foundation, curated by James Franco, Isaac Julien and Glenn Scott Wright Njideka Akunyili, Jules de Balincourt, Ali Banisadr, Hernan Bas, Joe Bradley, Cecily Brown, Peter Doig, Inka Essenhigh, Eric Fischl, Barnaby Furnas, David Harrison, Secundino Hernández, Nicholas Hlobo, Chantal Joffe, Sandro Kopp, Harmony Korine, Yayoi Kusama, Glenn Ligon, Wangechi Mutu, Alice Neel, Chris Ofili, Celia Paul, Philip Pearlstein, Elaine Reichek, Luc Tuymans, Adriana Varejão, Suling Wang, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Exhibition continues until 3 August 2013 Walking List The exhibition extends across both Victoria Miro gallery spaces, which are adjacent to one another. Victoria Miro No. 14 is accessed via the garden terrace of No. 16. Victoria Miro No. 16 Downstairs gallery. Clockwise from entrance. Chris Ofili Peter Doig Ovid-Windfall, 2011-2012 Two Students, 2008 Oil and charcoal on linen Oil on Paper 310 x 200 x 4 cm, 122 1/8 x 78 3/4 x 1 5/8 in 73 x 57.5 cms, 28.76 x 22.66 in Eric Fischl Alice Neel Victoria Falls, 2013 Ian and Mary, 1971 Oil on linen Oil on canvas 208.3 x 172.7 cm, 82 x 68 in 116.8 x 127 cm, 46 x 50 in Chantal Joffe Peter Doig Jessica, 2012 Trinidad & Tobago Film Festival, 2008 Oil on board Oil on paper 305 x 150 cm, 120 x 48 1/8 in 76 x 105.5 cm, 29 7/8 x 41 1/2 in Lynette Yiadom Boakye David Harrison Alive To Be Glad, 2013 Midnight Meet, 2011 Oil on canvas Oil on paper on board 200 x 160 cm, 78 3/4 x 63 in 50.7 x 40.5 x 42.5 cm, 20 x 16 x 16 3/4 in Celia Paul Painter and Model, 2012 Oil on canvas 137.2 x 76.2 cm, 54 x 30 in Victoria Miro No. -

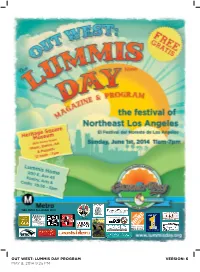

Lummis Day Program May 8, 2014 9:25 PM VERSION

take metro to Lummis Day! OUT WEST: LUmmiS Day PrOgram version: 6 May 8, 2014 9:25 PM Festival schedule Who’s On and When LUMMis hOMe aNd GaRdeN STagE Two famiLy acTiviTiES SPacE 200 East avenue 43 1:30 PM Arya Movement Project: Various Times gates open at 10:00am Sambasalsa! Urban Science Corps “EcoVoices” 10:30 AM Musical interlude by 2:45 PM Lineage Dance Company Navjot Sandhu 4:00 PM Danza Teocalt and Neel agrawal STagE fOUr 5:30 PM Chester Whitmore 11:00 AM Introduction and poem by 1:30 PM Michelle Rodriguez Suzanne Lummis STagE THrEE 2:15 PM Dead End Poets: Christopher Buckley, 1:00 PM Sweet DizPosition 3:00 PM BMC liz gonzaléz, and Mary Fitzpatrick 2:00 PM Banna Baeg Mall 4:00 PM The Slightlys Noon-5:00 PM Crafts and art exhibits 3:15 PM Smithfield Bargain 5:00 PM The Dead Sea Crows 4:30 PM Alarma heRITAGe sQUARe MuseuM 5:30 PM Somos Mysteriosos OtheR FaMily activities 3800 Homer Street (various locations at Heritage Square) gates open at noon OtheR PeRFORMaNce aReas Tongva Clapper Sticks staGe ONe LincOLn avEnUE cHUrcH 12:45 PM Ted Garcia, PErfOrmancE SPacE Home Depot/Color Spot Native america Blessing Transplanting Booth 2:40 PM, 4:00 PM Teatro arroyo’s 1:00 PM Timur and The Dime Museum “Dr. Madcap’s Theatricum” audubon Display and activity (plus 2:00 PM Blue Rhythm Jazz Orchestra andasol Elementary School Display) 3:20 PM Little Faith Puppets & PLayErS STagE Highland Park Heritage Trust 4:30 PM Orquesta Mar De ashe 1:20 PM, 3:00: PM, 4:30PM with La Sirena Puppets & Players: Living Museum Tour 6:00 PM La Chamba Scooter’s Circus