I Write This in the Month When We Mark the Fiftieth Anniversary of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lnt'l Protest Hits Ban on French Left by Joseph Hansen but It Waited Until After the First Round of June 21

THE INSIDE THIS ISSUE Discussion of French election p. 2 MILITANT SMC exclusionists duck •1ssues p. 6 Published in the Interests of the Working People Vol. 32- No. 27 Friday, July 5, 1968 Price JOe MARCH TO FRENCH CONSULATE. New York demonstration against re gathered at Columbus Circle and marched to French Consulate at 72nd Street pression of left in France by de Gaulle government, June 22. Demonstrators and Fifth Ave., and held rally (see page 3). lnt'l protest hits ban on French left By Joseph Hansen but it waited until after the first round of June 21. On Sunday, Dorey and Schroedt BRUSSELS- Pierre Frank, the leader the current election before releasing Pierre were released. Argentin and Frank are of the banned Internationalist Communist Frank and Argentin of the Federation of continuing their hunger strike. Pierre Next week: analysis Party, French Section of the Fourth Inter Revolutionary Students. Frank, who is more than 60 years old, national, was released from jail by de When it was learned that the prisoners has a circulatory condition that required of French election Gaulle's political police on June 24. He had started a hunger strike, the Commit him to call for a doctor." had been held incommunicado since June tee for Freedom and Against Repression, According to the committee, the prisoners 14. When the government failed to file headed by Laurent Schwartz, the well decided to go on a hunger strike as soon The banned organizations are fighting any charges by June 21, Frank and three known mathematician, and such figures as they learned that the police intended to back. -

English Translations) Miners to Get Another Master in in the Labor Movement, Has Given and a Cross Petition Has Been 17 Uprising

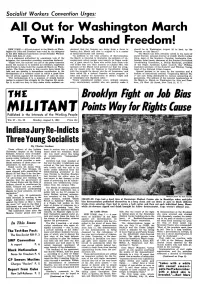

Socialist Workers Convention Urges: All Out for Washington March To Win Jobs and Freedom! NEW YORK — All-out support to the March on Wash derstand that the Negroes are doing them a favor in should be in Washington August 28 to back up the ington for Jobs and Freedom was voted by the delegates leading this March and that to support it is a matter Negroes on this March.” to the 20th National Convention of the Socialist Workers of bread-and-butter self interest. The March has been officially called in the name Of Party held here in July. “In addition to the vital problem of discrimination, James Farmer, national director of CORE; Martin Luther In a statement authorized by unanimous vote of the the March is intended to dramatize the problem of un King, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Con delegates, the convention presiding committee declared: employment which weighs most heavily on Negro work ference; John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent “Right now, the number one job of the party branches ers. A giant march by those who suffer from these evils Coordinating Committee; A. Phillip Randolph, president across the country is to mobilize all members, supporters w ill strike fear into their enemies on Capitol Hill. The of the Negro American Labor Council; Roy Wilkins, and friends to help build the August 28 March on Wash sponsors of the March have pointed out that the strug executive secretary of the NAACP; and Whitney Young, ington. The Negro people in this country have taken the gle for decent jobs for Negroes is ‘inextricably linked head of the National Urban League. -

Justice for Andrew Brown Jr

Espíritu del Primero de Mayo 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 63, No. 18 May 6, 2021 $1 Another police murder in North Carolina Justice for Andrew Brown Jr. By Peter Gilbert Elizabeth City, N.C. May 1— Seven deputies from the Pasquotank County Sheriff’s Department killed unarmed Andrew Brown Jr. in his car next to his home here April 21. The dep- uties jumped out of a pickup truck with weapons drawn and rushed forward. Fearing for his life, Brown tried to drive forward out of his driveway and away. Deputy sher- iffs fired into his car from behind, killing him. An autopsy commissioned by Brown’s family confirms he was killed by a bullet to the back of the Protests against police violence continue night and day in Elizabeth City, May 2. WW PHOTOS: PETER GILBERT head. At least three of the depu- ties fired their weapons; none of them have been charged. Four have been a kind man who provided for his family been a violent person in his life. He’s declined in prosperity. returned to active duty. despite the lack of jobs or opportunities in never had a gun, never carried a gun, and The swamp was once a haven for Protests have continued each night Elizabeth City. He lived in a quiet neigh- he’s just not violent." enslaved people who had liberated them- for ten nights since the police execution borhood south of downtown, across the selves from surrounding plantations. The of Andrew Brown Jr., as the community Charles Creek where he had been raised Enslavement, forced labor, militarism swamp played an important role as cover mourns. -

Désintégration Dans La « Période Post-Soviétique » La Spartacist League Soutient Les Troupes Américaines À Haïti !

No. 1 Second Quarter 2010 Contents On Optimism & Pessimism (1901) – by Leon Trotsky Resignation from the International Bolshevik Tendency The Road Out of Rileyville Introduction to Marxist Polemic Series League for the Revolutionary Party’s “Revisions of Basic Theory” Disintegration in the “Post-Soviet Period” Spartacist League Supports US Troops in Haiti! League for the Revolutionary Party/ Internationalist Socialist League on the Revolution in Palestine/ Israel Worshipers of the Accomplished Fact On Feminism & “Feminism” James P. Cannon’s “Swivel Chair Revelation” (1959) Désintégration dans la « période post-soviétique » La Spartacist League soutient les troupes américaines à Haïti ! Downloaded from www.regroupment.org Labor Donated Leon Trotsky on Optimism & Pessimism (1901) The following short excerpt by a young Leon Trotsky is being reprinted as the introduction for this journal’s first issue. It is symbolic of the journal’s determination to succeed in its endeavor and its underlying confidence in the capacity of the working class to break the chains of oppression and inaugurate a new chapter in human history. Samuel Trachtenberg May 1, 2010 Dum spiro spero! [While there is life, there‘s hope!] ... If I were one of the celestial bodies, I would look with complete detachment upon this miserable ball of dust and dirt ... I would shine upon the good and the evil alike ... But I am a man. World history which to you, dispassionate gobbler of science, to you, book-keeper of eternity, seems only a negligible moment in the balance of time, is to me everything! As long as I breathe, I shall fight for the future, that radiant future in which man, strong and beautiful, will become master of the drifting stream of his history and will direct it towards the boundless horizon of beauty, joy, and happiness! .. -

E!A!! by Barry Sheppard Later Scaled Down to 10,000

N. Y.Pro-War Marth TH£ A ResoundingFiasto Md~~~e!A!! By Barry Sheppard later scaled down to 10,000. The from the department of highways, police said 6,840. One reporter for Vol. 31 - No. 19 Monday, May 8, 1967 Price 10¢ NEW YORK - A march down etc. the New York Times counted Fifth Avenue in support of the A handful of despondent-looking 3,380, and another Times reporter, war in Vietnam on April 29, billed some blocks away, 3,717. marchers walked behind the "Wa by its sponsors as the "answer" ter Department" banner - no to the massive April 15 marches In a similar "Loyalty" march in against the war, was a dismal Brooklyn, police put the figure at doubt city employes dependent for flop. The fiasco clearly demon 4,500, just about the same figure their jobs on patronage, dragooned the Times reporter there gave. PeruvianGuards strated the lack of popular support out for the occasion. There were for this war. Even if one accepts .the police a few other such groups from The pro-war march, organized estimates - which were designed other city government depart by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, to minimize the massive antiwar took the form of the annual march and maximize the pitiful ments. pro-war march, the antiwar fight Besides VFW units, there were BeatUp Blanco "Loyalty Day" parade. "Loyalty Day" itself was set up in 1947 ers outdid the war fanatics by contingents from some military (World Outlook) - The Paris rid of Hugo Blanco. In view of the as the "answer" to May Day, the about 9 to 1! The real figures high schools, military reserve office of World Outlook learned worldwide publicity in the case, international workers' holiday. -

A Spartacist Pamphlet 75¢

A Spartacist Pamphlet 75¢ On the ivil Rights Movement ·~~i~;~~·X523 Spartacist Publishing Co., Box 1377 GPO, New York, N.Y. 10116 ---------,.,," ._-- 2 Table of Introduction Contents When on I December 1955 Rosa open the road to freedom for black Parks of Montgomery, Alabama re people. With this understanding the fused to give up her seat on a bus to a early Spartacist tendency fought to Introduction ................ 2 white man, she sparked a new and break the civil rights militants from the convulsive period in modern American Democratic/ Dixiecratic Party and to history. For over a decade black forge a Freedom/Labor Party, linking -Reprinted from Workers Vanguard struggle for equality and democratic the mass movement for black equality No. 207, 26 May 1978 rights dominated political life in this with the working-class struggle against country. From the lunch counter sit-ins Ten Years After Assassination capital. and "freedom rides" in the Jim Crow The reformist "left" groups, particu Bourgeoisie Celebrates South to the ghetto explosions in the larly the Communist Party and Socialist King's Liberal Pacifism .... 4 North, black anger shook white racist Party, sought actively to keep the America. explosive civil rights activism "respect Amid the present anti-Soviet war able" and firmly in the death-grip of the -Reprinted from Young Spartacus Nos. 115 hysteria of the Reagan years, it is white liberals and black preachers. For and 116, February and March 1984 important to recall an aspect of the civil example the SP was hand in glove with The Man That rights movement which is now easily the establishment black leaders in Liberals Feared and Hated forgotten. -

FEDERAL ELECTIONS 2018: Election Results for the U.S. Senate and The

FEDERAL ELECTIONS 2018 Election Results for the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives Federal Election Commission Washington, D.C. October 2019 Commissioners Ellen L. Weintraub, Chair Caroline C. Hunter, Vice Chair Steven T. Walther (Vacant) (Vacant) (Vacant) Statutory Officers Alec Palmer, Staff Director Lisa J. Stevenson, Acting General Counsel Christopher Skinner, Inspector General Compiled by: Federal Election Commission Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Office of Communications 1050 First Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20463 800/424-9530 202/694-1120 Editors: Eileen J. Leamon, Deputy Assistant Staff Director for Disclosure Jason Bucelato, Senior Public Affairs Specialist Map Design: James Landon Jones, Multimedia Specialist TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface 1 Explanatory Notes 2 I. 2018 Election Results: Tables and Maps A. Summary Tables Table: 2018 General Election Votes Cast for U.S. Senate and House 5 Table: 2018 General Election Votes Cast by Party 6 Table: 2018 Primary and General Election Votes Cast for U.S. Congress 7 Table: 2018 Votes Cast for the U.S. Senate by Party 8 Table: 2018 Votes Cast for the U.S. House of Representatives by Party 9 B. Maps United States Congress Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Campaigns 11 Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Victors by Party 12 Map: 2018 U.S. Senate Victors by Popular Vote 13 Map: U.S. Senate Breakdown by Party after the 2018 General Election 14 Map: U.S. House Delegations by Party after the 2018 General Election 15 Map: U.S. House Delegations: States in Which All 2018 Incumbents Sought and Won Re-Election 16 II. -

1 Revolutionary Communist Party

·1 REVOLUTIONARY COMMUNIST PARTY (RCP) (RU) 02 STUDENTS FOR A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY 03 WHITE PANTHER PARTY 04 UNEMPLOYED WORKERS ORGANIZING COMMITTE (UWOC) 05 BORNSON AND DAVIS DEFENSE COMMITTE 06 BLACK PANTHER PARTY 07 SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY 08 YOUNG SOCIALIST ALLIANCE 09 POSSE COMITATUS 10 AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT 11 FRED HAMPTION FREE CLINIC 12 PORTLAND COMMITTE TO FREE GARY TYLER 13 UNITED MINORITY WORKERS 4 COALITION OF LABOR UNION WOMEN 15 ORGANIZATION OF ARAB STUDENTS 16 UNITED FARM WORKERS (UFW) 17 U.S. LABOR PARTY 18 TRADE UNION ALLIANCE FOR A LABOR PARTY 19 COALITION FOR A FREE CHILE 20 REED PACIFIST ACTION UNION 21 NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN (NOW) 22 CITIZENS POSSE COMITATUS 23 PEOPLE'S BICENTENNIAL COMMISSION 24 EUGENE COALITION 25 NEW WORLD LIBERATION FRONT 26 ARMED FORCES OF PUERTO RICAN LIBERATION (FALN) 1 7 WEATHER UNDERGROUND 28 GEORGE JACKSON BRIGADE 29 EMILIANO ZAPATA UNIT 30 RED GUERILLA FAMILY 31 CONTINENTAL REVOLUTIONARY ARMY 32 BLACK LIBERATION ARMY 33 YOUTH INTERNATIONAL PARTY (YIPPY) 34 COMMUNIST PARTY USA 35 AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE 36 COALITION FOR SAFE POWER 37 IRANIAN STUDENTS ASSOCIATION 38 BLACK JUSTICE COMMITTEE 39 PEOPLE'S PARTY 40 THIRD WORLD STUDENT COALITION 41 LIBERATION SUPPORT MOVEMENT 42 PORTLAND DEFENSE COMMITTEE 43 ALPHA CIRCLE 44 US - CHINA PEOPLE'S FRIENDSHIP ASSOCIATION 45 WHITE STUDENT ALLIANCE 46 PACIFIC LIFE COMMUNITY 47 STAND TALL 48 PORTLAND COMMITTEE FOR THE LIBERATION OF SOUTHERN AFRICA 49 SYMBIONESE LIBERATION ARMY 50 SEATTLE WORKERS BRIGADE 51 MANTEL CLUB 52 ......., CLERGY AND LAITY CONCERNED 53 COALITION FOR DEMOCRATIC RADICAL MOVEMENT 54 POOR PEOPLE'S NETWORK 55 VENCEREMOS BRIGADE 56 INTERNATIONAL WORKERS PARTY 57 WAR RESISTERS LEAGUE 58 WOMEN'S INTERNATIONAL LEAGUE FOR PEACE & FREEDOM 59 SERVE THE PEOPLE INC. -

Psychological and Personality Profiles of Political Extremists

Psychological and Personality Profiles of Political Extremists Meysam Alizadeh1,2, Ingmar Weber3, Claudio Cioffi-Revilla2, Santo Fortunato1, Michael Macy4 1 Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA 2 Computational Social Science Program, Department of Computational and Data Sciences, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA 3 Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar 4 Social Dynamics Laboratory, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Abstract Global recruitment into radical Islamic movements has spurred renewed interest in the appeal of political extremism. Is the appeal a rational response to material conditions or is it the expression of psychological and personality disorders associated with aggressive behavior, intolerance, conspiratorial imagination, and paranoia? Empirical answers using surveys have been limited by lack of access to extremist groups, while field studies have lacked psychological measures and failed to compare extremists with contrast groups. We revisit the debate over the appeal of extremism in the U.S. context by comparing publicly available Twitter messages written by over 355,000 political extremist followers with messages written by non-extremist U.S. users. Analysis of text-based psychological indicators supports the moral foundation theory which identifies emotion as a critical factor in determining political orientation of individuals. Extremist followers also differ from others in four of the Big -

Marxist Politics Or Unprincipled Combinationism?

Prometheus Research Series 5 Marxist Politics or Unprincipled Combinationism? Internal Problems of the Workers Party by Max Shachtman Reprinted from Internal Bulletin No. 3, February 1936, of the Workers Party of the United States With Introduction and Appendices , ^3$ Prometheus Research Library September*^ Marxist Politics or Unprincipled Combinationism? Internal Problems of the Workers Party by Max Shachtman Reprinted from Internal Bulletin No. 3, February 1936, of the Workers Party of the United States With Introduction and Appendices Prometheus Research Library New York, New York September 2000 Prometheus graphic from a woodcut by Fritz Brosius ISBN 0-9633828-6-1 Prometheus Research Series is published by Spartacist Publishing Co., Box 1377 GPO, New York, NY 10116 Table of Contents Editorial Note 3 Introduction by the Prometheus Research Library 4 Marxist Politics or Unprincipled Combinationism? Internal Problems of the Workers Party, by Max Shachtman 19 Introduction 19 Two Lines in the Fusion 20 The "French" Turn and Organic Unity 32 Blocs and Blocs: What Happened at the CLA Convention 36 The Workers Party Up To the June Plenum 42 The Origin of the Weber Group 57 A Final Note: The Muste Group 63 Conclusion 67 Appendix I Resolution on the Organizational Report of the National Committee, 30 November 1934 69 Appendix II Letter by Cannon to International Secretariat, 1 5 August 1935 72 Letter by Glotzer to International Secretariat, 20 November 1935 76 Appendix III National Committee of the Workers Party U.S., December 1934 80 Glossary 81 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/marxistpoliticsoOOshac Editorial Note The documents in this bulletin have in large part been edited for stylistic consistency, particularly in punctuation, capitalization and emphasis, and to read smoothly for the modern reader. -

The Government Doesn't Work

World capital and Thelma and Louise Stalinism slew the "R" Us, writes Soviet economy Clara Fraser Page 6 Page 9 ~ Freedom Socialist Wile 1? /?evpf"'fl1t4~ 1iMiN;M. May-July 1992 Volume 13, Number 3 (51.00 outside U.S.) 75c Let's tool up for a new system! . The government doesn't work BY MATT NAGLE ing-class white men are under at n the good 01' USA, the sun is shin tack in the streets, ing, the birds are singing, the flow courts, and legis ers are blooming - but the govern latures. Unions are Iment is sputtering, hacking and besieged, radicals wheezing in the throes of terminal do are persecuted. nothingness. The cities are poi We should all be delighted! soned war zones The fact that this inhuman, infernal, and the earth is be damned system is rapidly killing itself ing destroyed. means our chance to bust out of these So the politi dark days is tantalizingly close. cians talk about The U.S. government has developed meeting our needs, into a tiresome, petty passel of squab but they can't and .=============="":"'"=~ bling, spoiled rich kids and everybody won't do anything. ~.MFoi~tr.RK_flMI!JiN;.IbaI~iMH!Hl··~_IJIbo~iIoU;.,"'""'-l.&.lu~~~~ ~~ to' a halt '\'fet'clU'se' th~'~pita\ls't'S)'.nem ,.~ problem~rwtthc that the government administers is out changing the cracking up. system - and they The Democrats and Republicans are are the system. feudin' like the Hatfields and McCoys. Leaders don't The Dems don't have the guts or a emerge from cess reason to stand up to the Republicans, pools. -

Freedom Socialist Party Review of International Conference

London antifascist conference sabotaged by sectarian politics of its organizers Luma Nichol January 1998 Along with other questions, the registration form for the International Militant Anti-Fascism Conference in London in October asked if participants wanted to play football. Once I arrived, therefore, I wasn't surprised when the convening group, Anti-Fascist Action (AFA), turned out to be almost entirely male (not that women can't be gridiron contenders!) But I was delighted to see women introducing delegations from Scandinavia, Germany, Spain, and the U.S. Contingents also attended from Scotland, Ireland, England, the Netherlands, France, and Canada, and I represented United Front Against Fascism, a Seattle-based education and direct action organization. Our goal was to discuss forming an international anti-fascist network. But unfortunately, AFA turned out to be vehemently sexist and anti-communist. Its political deficiencies sabotaged the conference - which, due to AFA's outreach, was overwhelmingly white and did not include groups representing immigrants, sexual minorities, Romanis (Gypsies) or Jews, all main targets of fascist violence. AFA's leaders blame the current resurgence of fascism on the "old Left," which they believe is dead and discredited. They focus AFA's energy on trying to keep communists out of "their" movement rather than on uniting anti-fascists against the ultraright. Ironically, they are following the tragically wrong path of the German Communist Party in the 1930s; the CP saw reformist socialists as worse than the Nazis and refused to join with them to stop Hitler. The good news: AFA's views were not held by the majority.