May 2010 Edited Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Cadre SST Posts by Directorate of Elementary and Secondary Education, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar (Screening Test)

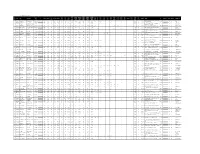

District Cadre SST Posts by Directorate of Elementary and Secondary Education, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar (Screening Test) Test held on 4th December 2016 Provisional Merit List For Interview Swat Male SST (General) SSC Sr RollNo Name NIC Gender Domicile Obt Name of school apply for 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHS SHINKOO 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHSS KALAM 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHSS MANKYAL 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GHSS SAKHRA 1 783001235 BARKAT ALI 15602-4130615-9 MALE SWAT 609.0 GMS BASHIGRAM 1 783001083 USAMA AZEEM 15601-7397921-5 MALE SWAT 579.0 GHS GAT 2 783001083 USAMA AZEEM 15601-7397921-5 MALE SWAT 579.0 GHSS SAKHRA District Cadre SST Posts by Directorate of Elementary and Secondary Education, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar (Screening Test) Test held on 4th December 2016 Provisional Merit List For Interview Swat Male SST (General) SSC HSSC Bachelor BS Hons. Master 15 Total 20% (A) Obt Total 20% (B) Obt Total 20% (C) Obt Total 35% (C) Obt Total % (D) 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 900.0 13.53 780.0 1100.0 14.18 316.0 550.0 11.49 0.0 0.0 0.0 614.0 1100.0 8.37 850.0 13.62 867.0 1400.0 12.39 2370.0 3400.0 13.94 0.0 0.0 0.0 745.0 1000.0 -

Lower Dir - Who Does What and Where Date (08 Feb 2010)

Lower Dir - Who does What and Where Date (08 Feb 2010) Tehsil Union Council Cluster Organisation Funding Organisation Tehsil Union Council Cluster Organisation Funding Organisation Adenzai Tazagram Agriculture IRC DFID Temergara Balambat Agriculture ACTED FAO/WFP Shelter and NFI WASH Shelter and NFI ACTED IOM CR MCIDP OTI Agriculture Camp Managment Nutrition IOM SIDA Health ABKT Planned IRC OFDA-DFID WV WV WASH ACTED DFID Nutrition RI UNICEF Protection UPPER DIR UPPER DIR UPPER DIR UPPER DIR UPPER DIR IRC OFDA-DFID IOM IOM Blambat Manjai CR IOM OFDA Bandagai Education MCIDP OTI T Hayaseri Hayaseri Agriculture IRC DFID Health ABKT Planned Education KK UNDP Nutrition RI UNICEF F Health ABKT Planned Protection IOM IOM Protection SPADO UNICEF SPADO UNICEF Shelter and NFI ACTED IOM Bishgram Education KK UNDP A ICRC/PRCS ICRC Food ICRC/PRCS ICRC IOM SIDA Nutrition CERD UNICEF IRC OFDA-DFID Protection IOM IOM LOWER DIR R LOWER DIR LOWER DIR WASH IRC OFDA-DFID Shelter and NFI ACTED IOM LOWER DIR LOWER DIR Jandool Darangal Nutrition CERD UNICEF ICRC/PRCS ICRC Protection IOM IOM IOM SIDA D Khazana Food ICRC/PRCS ICRC Chakdara CR ABKT Planned Nutrition RI UNICEF Nutrition CERD UNICEF Protection IOM IOM Protection IOM IOM Mayar Food ICRC/PRCS ICRC Shelter and NFI ACTED IOM Nutrition CERD UNICEF IOM SIDA SWAT SWAT SWAT SWAT SWAT Protection IOM IOM WASH ACTED DFID SPADO UNICEF Dushkhil Health ABKT Planned MOHMAND AGENCY MOHMAND AGENCY MOHMAND AGENCY MOHMAND AGENCY MOHMAND AGENCY Mian Kili Food ICRC/PRCS ICRC Gail Maidan Food ACTED WFP MALAKAND PA MALAKAND -

Annual Development Programme

ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 16 - PROGRAMME 2015 PROGRAMME DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT JUNE, 2015 www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk FINAL ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2015-16 GOVERNMENT OF KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT http://www.khyberpakhtunkhwa.gov.pk Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Table of Contents S.No. Sector/Sub Sector Page No. 1 Abstract-I i 2 Abstract-II ii 3 Abstract-III iii 4 Abstract-IV iv-vi 5 Abstract-V vii 6 Abstract-VI viii 7 Abstract-VII ix 8 Abstract-VIII x-xii 9 Agriculture 1-21 10 Auqaf, Hajj 22-25 11 Board of Revenue 26-27 12 Building 28-34 13 Districts ADP 35-35 14 DWSS 36-50 15 E&SE 51-60 16 Energy & Power 61-67 17 Environment 68-69 18 Excise, Taxation & NC 70-71 19 Finance 72-74 20 Food 75-76 21 Forestry 77-86 22 Health 87-106 23 Higher Education 107-118 24 Home 119-128 25 Housing 129-130 26 Industries 131-141 27 Information 142-143 28 Labour 144-145 29 Law & Justice 146-151 30 Local Government 152-159 31 Mines & Minerals 160-162 32 Multi Sectoral Dev. 163-171 33 Population Welfare 172-173 34 Relief and Rehab. 174-177 35 Roads 178-232 36 Social Welfare 233-238 37 Special Initiatives 239-240 38 Sports, Tourism 241-252 39 ST&IT 253-258 40 Transport 259-260 41 Water 261-289 Abstract-I Annual Development Programme 2015-16 Programme-wise summary (Million Rs.) S.# Programme # of Projects Cost Allocation %age 1 ADP 1553 589965 142000 81.2 Counterpart* 54 19097 1953 1.4 Ongoing 873 398162 74361 52.4 New 623 142431 35412 24.9 Devolved ADP 3 30274 30274 21.3 2 Foreign Aid* * 148170 32884 18.8 Grand total 1553 738135 174884 100.0 Sector-wise Throwforward (Million Rs.) S.# Sector Local Cost Exp. -

(I) Kabal BAR ABA KHEL 2 78320

Appointment of Teachers (Adhoc School Based) in Elementary & Secondary Education department, Khyber Pakhutunkhwa (Recruitment Test)) Page No.1 Test held on 20th, 26th & 27th November 2016 Final Merit List (PST-Male) Swat NTS Acad:Ma Marks SSC HSSC Bachelor BS Hons. Master M.Phill Diploma M.Ed/MA.Ed rks [out of 100] [Out of 100] Total (H=A+B+ Candidate RollN Date Of 20% 35% 15% 5% 15% Marks [Out Father Name Total 20% (A) Obt Total 20% (B) Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total 5% (G) C+D+E+ Mobile Union Address REMARKS Tehsil Sr Name School Name Obt (I) of 200] o Birth (C) (C) (D) (E) (F) F+G) Name U.C Name apply for J=H+I Council GPS 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 2 CHINDAKHW AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 ARA 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 GPS DERO AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 CHUM 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 GPS KABAL 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE -

Final Short Listed Candidates for the Post of Chowkidar BPS-03 1

Final Short Listed Candidates for the Post of Chowkidar BPS-03 1 S.No Application No. Name Father Name CNIC No. Address Remarks 1 4186 Abbas Khan Ajab Khan 16101-1106142-7 Village Bughdada Mohallah Mianz Kandi Tehsil & Dis 2 8648 Abbas khan Akbar khan 15302-7569697-7 Village kandaro payee p/o timergara tehsil balamba 3 17177 Abbas khan Muhammad Sarwar 15602-0357410-5 The City School near to wali swat palace Saidu,Sha 4 1880 ABDUL BASIR RAHMAN ULLAH 13403-0165401-5 MAHALA KHAIR ABAD CHINAR TANGAY QAMBER P/O RAHIMA 5 13949 Abdul Ghani Abdul Ghafoor 15602-8590425-5 Watershed Colony Shagai Saidu Sharif, Swat 6 459 Abdul Hakim Abdul Qayyum 15602-7736472-5 National Central Hospital near old Nadra office Sa 7 4347 Abdul hamid Muhammad Yousaf 15602-0333476-1 PHC Mingora Bench/Dar-ul-Qaza, Swat 8 19082 Abdul Haq Abdul Wahid 15602-4790389-1 Mohalla Farid Abad Vilage Gul Kada No:3 Post Offi 9 14491 Abdul Jabar Khan Abdul Sattar 17101-6547652-7 PO Mohallah Qazi Khel Jaded District Charsadda 10 5437 Abdul Jabbar Saeed Ahmed Gul 17301-2992986-1 Subhash Educational Complex G.T Road, Hashtnagri P 11 3080 Abdul Jalil Bakht Munir 21104-4193372-9 P/o and tehsil khar Bajur KPK 12 745 Abdul Kabir Muhammad ismail 15607-0358002-1 Mohallah miangan Village and p/o haji baba road ko 13 16078 Abdul Kareem Abdul Jamil 15602-9132021-3 Akhoon baba Shagai Saidu Sharif Swat kpk 14 8254 abdul nasior Abdur raziq marhom 15602-0472344-7 Spin lala Medicose Zardad market Neshat chwak min 15 12747 Abdul Qayyum Muhammad ibrahim 17301-7497146-5 Good luck tailor 2nd floor sittara -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Assistant Director

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF ASSISTANT DIRECTOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS & RURAL DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT AND SELECTED VILLAGE COUNCILS / NEIGHBORHOOD COUNCILS DISTRICT SWAT KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................... i Preface .............................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ......................................................................... vii I: Audit Work Statistics ........................................................................................... vii II: Audit observations classified by Categories ........................................................ vii III: Outcome Statistics .............................................................................................viii IV: Irregularities pointed out ..................................................................................... ix V: Cost-Benefit ........................................................................................................ ix CHAPTER-1 .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Assistant Director LGE&RDD and NCs/VCs District Swat ..................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction -

Check List Act Appeals Format

SECRETARIAT 150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland TEL: +41 22 791 6033 FAX: +41 22 791 6506 www.actalliance.org Appeal- Revision 1 Pakistan Post-conflict rehabilitation in North West Frontier Province (PAK101) Appeal Target: US$ 3,956,072 Balance Requested: US$ 3,811,072 5 May 2010 Dear colleagues, This version of the PAK101 appeal has been revised to include a proposed programme of ACT Alliance member Church World Service (CWS). This appeal was launched on March 31st 2010 to follow on from ACT appeal PAK091 supporting people displaced by conflict in 2009. The purpose of this programme is to contribute to the long-term recovery process for the 1.8 million women, men and children who were displaced. This includes both returnees and those who stayed behind during the fighting in their places of origin in the Swat and Buner Districts of the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). Church World Service (CWS) proposes recovery assistance to conflict-affected returnees and other community members in the areas of return including livelihoods rehabilitation related to food-production, education, and primary health care services in Buner and Swat districts over a 12 month project timeframe. For livelihoods work in Buner, CWS will work with local partner organization Lasoona. Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) proposes to assist 3,383 families in Swat and Buner to ensure their access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, with a particular focus on access for women and girls, the elderly and disabled. Schools’ water and sanitation needs in the identified target areas will be included wherever possible. -

FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Nutrition Presence of Partners - F.A.T.A. and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 29 November 2010 Legend CHITRAL Provincial Boundar Kalam Utror District Boundary Number of Implementing Partners KOHISTAN Balakot 1 2 SWAT Mankyal UPPER DIR Bahrain 3 Gowalairaj Madyan PESHAWAR Beshigram Beha Sakhra Bar Thana Fatehpur Gail Maidan Zaimdara Asharay Darangal Baidara Bishgram ShawarChuprial Miskana Shalpin Urban-4 Lal Qila Tall Arkot Shahpur Usterzai Samar Bagh Lijbook Jano/chamtalai Muhammad Zai Mayar Kala Kalay Alpuri Kuz Kana Urban-3 Koto Pir Kalay Munjai Shah DehraiDewlai Urban-5 Mian Kili Balambat Bara Bandai SHANGLADherai Opal Rabat Totano Bandai Kech Banda Togh Bala Munda QalaKhazanaBandagai HazaraKanaju Malik Khel Chakesar Urban-6 Kotigram Asbanr Puran Ganjiano Kalli Raisan Shah Pur Bahadar Kot 1 LOWER DIRMc Timargara Koz Abakhel Kabal BATAGRAM Khanpur Billitang Ziarat Talash Aloch HANGU Ouch Kokarai Kharmatu Bagh Dush Khel Chakdara Islampur Kotki KOHAT Khadagzai AbazaiBadwan Sori Chagharzai Gul BandaiBehlool Khail Kota Dhoda Daggar Batara MALAKAND Pandher Rega MANSEHRA BUNER Krapa Gagra Norezai KARAK MARDAN CHARSADDA Kangra Rajjar IiShakho KYBER PAKHTUNKHWA Hisar Yasinzai Dosahra Nisatta Dheri Zardad SWABI ABBOTTABAD Mohib Banda ChowkaiAman Kot M.c Pabbi HARIPUR PESHAWAR NOWSHERA Shah Kot Usterzai Urban-4 Kech Banda Urban-6Togh Bala Raisan Khan Bari Shah Pur Kotki KharmatuBillitang KOHAT HANGU Dhoda Muhammad Khawja This map illustrates the presence of organisations working in the sector of Nutrition in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA as reported by relief -

Revision of Election Electoral Rolls

Changes involved (if DISTRICT TEHSIL QH PC VILLAGE CRCODE NAME DESG PHONE ADDRESS any) i.e. Retirement, Transfer etc 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH QAMBAR PC 0070101 ANWAR ALI SST 03025740801 GHS GOGDARA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MINGORA PC 0070102 HAZRAT HUSSAIN CT 03349321527 GHS NO,4 MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH SAIDU SHARIF PC 0070103 MUZAFAR HUSSAIN SCT 03449895384 GHS BANR MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MARGHAZAR PC 0070104 SHAMROZ KHAN SST,3 03345652060 GHS CHITOR SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH JAMBIL PC 0070105 ANWAR ULLAH SST 03429209704 GHS KOKARAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH KOKARAI PC 0070106 MINHAJ PSHT 03149707774 GPS KOKARAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH MANGLAWAR PC 0070107 SAID AKRAM SHAH NULL 03459526902 GPS TOTKAI SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH BISHBANR PC 0070108 ABDUL QAYUM PSHT 03459522939 GPS WARA SAR SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH SARSARDARAY PC 0070109 M. KHALIQ PSHT 03449892194 GPS DIWAN BAT SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH ODIGRAM PC 0070110 ASGHAR KHAN PET 03469411106 GHS TINDODOG SWAT BABUZAI BABUZAI QH ODIGRAM PC 0070110 PARVANAT KHAN HM 03450384634 GHS GOGDARA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 01 0070201 SHER AFZAL KHAN SST NULL GHS NO.1 SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 02 0070202 AMIR MOHAMMAD SCT NULL GHSS HAJI BABA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 03 0070203 ZAHID KHAN SCT NULL GHSS HAJI BABA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. CHARGE NO 02 CIRCLE NO 04 0070204 MUHAMMAD RAHIM SST NULL GHS NO.1 MINGORA SWAT BABUZAI MINGORA M.C. -

FTS at Merit List Male Swat Serial No Roll No Name Father Name Date Of

FTS AT Merit list Male Swat Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor Bachelor M.Phil/ Total Serial Date of SSC HSSC HSSC HSSC (14 (16 Years) / (16 Years) / (16 Years) / B.Ed B.Ed B.Ed M.Ed M.Ed M.Ed M.Phil/ M.Phil/ PhD PhD FTS Roll No Name Father Name NIC Gender Domicile SSC Total SSC Score (14 Years) (14 Years) MS PhD Total ACAD TotalScore Address City Mobile No Religion Disability Candidate UC No Birth Obtain Obtain Total Score Years) Master Master Master Obtain Total Score Obtain Total Score MS Total MS Score Obtain Score Marks Total Score Obtain Score Obtain Obtain Total Score PLOT NO 106/07 SEC 6 E LERP HAWKS BOY SCHEME 1 40465823 HAFIZ AIJAZ ALI MUHAMMAD ALI 11/18/1986 ############## Male Swat 524 850 12.329 701 1100 12.745 662 1000 13.24 695 1000 13.9 600 900 3.333 3.4 4 4.25 304 400 3.8 0 63.597 68 131.597 KARACHI ############# Muslim No KOTA 42 MUSHARRAF COLONY 2 40465697 SAEED UR REHMAN ABDUL WAHAR 2/20/1990 ############## Male Swat 529 800 13.225 521 1100 9.473 279 550 10.145 631 1100 11.473 0 0 0 0 44.316 86 130.316 VILLAGE AND PO SAKHRA MATTA Swat ############# N/A No SAKHRA MATTA TEHSIL TAKHT BHAI P/O LUND KHWAR JAMMIA 3 40125383 DAWOOD ALI MOHAMMAD RASHAD 3/1/1990 ############## Male Swat 830 1050 15.81 794 1100 14.436 344 550 12.509 481 600 16.033 599 900 3.328 0 0 0 62.116 68 130.116 Mardan ############# Muslim No KOZ ABA KHEL ISLAMIA MOHALA HOTI KHER MUHALLA MAZID KHEL NEAR SUNEHRI MASJID 4 40465683 FARHAD KHAN HABIB ULLAH KHAN 5/25/1993 ############## Male Swat 742 1050 14.133 739 1100 13.436 640 1000 12.8 1081 -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Council And

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT COUNCIL AND MUNICIPAL COMMITTEES SWAT AUDIT YEAR 2014-2015 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................... i PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ......................................................................... vii I Audit Work Statistics .......................................................................................... vii II: Audit observations classified by Categories ..................................................... vii III: Outcome Statistics ..........................................................................................viii IV: Irregularities pointed out .................................................................................. ix V: Cost-Benefit ...................................................................................................... ix CHAPTER-1 .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Municipal Committees and District Council of District Swat .................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (variance -

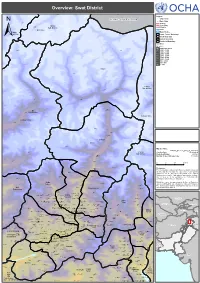

Swat District !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties.