Hungarian Peasant Customs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218

IACOBVS REVIST A DE ESTUDIOS JACOBEOS Y MEDIEVALES C@/llOj. ~1)OI I 1 ' I'0 ' cerrcrzo I~n esrrrotos r~i corrnrro n I santiago I ' s a t'1 Cl fJ r1 n 13-14 SAHACiVN (LEON) - 2002 CENTRO DE ESTVDIOS DEL CAMINO DE SANTIACiO The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218 Laszlo VESZPREMY Instituto Historico Militar de Hungria Resumen: Las relaciones entre los cruzados y el Reino de Hungria en el siglo XIII son tratadas en la presente investigacion desde la perspectiva de los hungaros, Igualmente se analiza la politica del rey cruzado magiar Andres Il en et contexto de los Balcanes y del Imperio de Oriente. Este parece haber pretendido al propio trono bizantino, debido a su matrimonio con la hija del Emperador latino de Constantinopla. Ello fue uno de los moviles de la Quinta Cruzada que dirigio rey Andres con el beneplacito del Papado. El trabajo ofre- ce una vision de conjunto de esta Cruzada y del itinerario del rey Andres, quien volvio desengafiado a su Reino. Summary: The main subject matter of this research is an appro- ach to Hungary, during the reign of Andrew Il, and its participation in the Fifth Crusade. To achieve such a goal a well supported study of king Andrew's ambitions in the Balkan region as in the Bizantine Empire is depicted. His marriage with a daughter of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople seems to indicate the origin of his pre- tensions. It also explains the support of the Roman Catholic Church to this Crusade, as well as it offers a detailed description of king Andrew's itinerary in Holy Land. -

Department of Human Geography & Planning, Faculty of Geosciences

Department of Human Geography & Planning, Faculty of Geosciences KLEMENTYNA GĄSIENICA – BYRCYN Student number: 3202739 THE INFLUENCE OF THE PROPERTY RESTITUTION IN THE TATRA MOUNTAINS ON THEIR CURRENT AND FUTURE NATURE PROTECTION MANAGEMENT Master thesis Human Geography and Spatial Planning Written under the supervision of Dr Hans Renes UTRECHT 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This Master thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and help of several individuals who in one way or another contributed and extended their valuable assistance in the preparation and completion of this study. First and foremost, my utmost gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Hans Renes, whose direction, assistance, and guidance enabled me to accomplish thesis research work. Furthermore, I would like to thank Dr Barbara Chovancová and Dr Milan Koreň from the State Forest of TANAP, Slovakia who despite the distance have scrupulously provided me with the information I needed. I am also indebted to my parents, Bożena and Wojciech Gąsienica-Byrcyn, without whose moral support, and steadfast encouragement to complete this study this thesis would not be made possible. Last but not the least, I offer my regards to all interviewees who supported me in any respect during the completion of the project. 2 TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 2. Terminology ........................................................................................................................ -

The Clash Between Pagans and Christians: the Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309

The Clash between Pagans and Christians: The Baltic Crusades from 1147-1309 Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Donald R. Shumaker The Ohio State University May 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Heather J. Tanner, Department of History 1 The Baltic Crusades started during the Second Crusade (1147-1149), but continued into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands, the Baltic Crusades were implemented in order to combat the pagan tribes in the Baltic. These crusades were generally conducted by German and Danish nobles (with occasional assistance from Sweden) instead of contingents from England and France. Although the Baltic Crusades occurred in many different countries and over several centuries, they occurred as a result of common root causes. For the purpose of this study, I will be focusing on the northern crusades between 1147 and 1309. In 1309 the Teutonic Order, the monastic order that led these crusades, moved their headquarters from Venice, where the Order focused on reclaiming the Holy Lands, to Marienberg, which was on the frontier of the Baltic Crusades. This signified a change in the importance of the Baltic Crusades and the motivations of the crusaders. The Baltic Crusades became the main theater of the Teutonic Order and local crusaders, and many of the causes for going on a crusade changed at this time due to this new focus. Prior to the year 1310 the Baltic Crusades occurred for several reasons. A changing knightly ethos combined with heightened religious zeal and the evolution of institutional and ideological changes in just warfare and forced conversions were crucial in the development of the Baltic Crusades. -

Maria Laskaris and Elisabeth the Cuman: Two Examples Of

Zuzana Orságová MARIA LASKARIS AND ELISABETH THE CUMAN: TWO EXAMPLES OF ÁRPÁDIAN QUEENSHIP MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2009 MARIA LASKARIS AND ELISABETH THE CUMAN: TWO EXAMPLES OF ÁRPÁDIAN QUEENSHIP by Zuzana Orságová (Slovakia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2009 MARIA LASKARIS AND ELISABETH THE CUMAN: TWO EXAMPLES OF ÁRPÁDIAN QUEENSHIP by Zuzana Orságová (Slovakia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2009 MARIA LASKARIS AND ELISABETH THE CUMAN: TWO EXAMPLES OF ÁRPÁDIAN QUEENSHIP by Zuzana Orságová (Slovakia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted -

Remarks on Andrew III of Hungary

KOSZTOLNYIK, Z. J. Remarks on Andrew III of Hungary Did his recognition of the privileges of the lesser nobility, and the dynastic marriages of the Arpdds, aid Andrew III of Hungary in retaining his throne? Et consensu uenerabilium patrum archiepiscoponim, episcopo- rum, baronum, procerum, et omnium nobilium regni nostri, apud Albam, in loco nostro catedrali, ... habita congrcgacione gene- rali, ... nobilium a sancto progenitoribus nostris data et concessa, que in articulis exprimuntur infrascripluris, ... firma fide promis- imus obseruare. Andrew III at the Diet of 1290 Dw his western upbringing, the experience his father, Prince Stephen, had gained during his sojourn at the court of his relative, James I of Aragon, or the family relations the Arpdds of Hungary had established with the ruling dynasty in Aragon during the thirteenth century, influence the domestic policies and foreign diplomacy of Andrew III of Hungary (1290—1301), determine the social constitu- ency of the diets of 1290 and 1298, and prevent realization of Angevin claims to his throne?1 The „family" data in the Hungarian2 and non-Hungarian chronicles,3 royal writs and diplomas,4 the related correspondence of the Holy See,5 and the letter Andrew III wrote after his coronation to another Aragonese relative, James II of 1 For text, cf. H. Marczali (ed), Enchiridion fontíttm históriáé Hungaronun (Budapest, 1901), cited hereafter as Marczali, Enchiridion, 186ff., and 191ff.; also, St. L. Endlicher (ed), Rerum Hungaricarum monumenta Arpadiana (Sanklgallen, 1849; repr. Leipzig, 1931), cited hereafter as RHM, 615ff., and 630ff.; Akos v. Timon, Ungarische Verfassungs- und Rechtsgeschichte, 2nd ed.. tr. Felix Schiller (Berlin, 1904), 318f.; Bálint Hóman — Gyula Szekfű, Magyar történet [Hungarian history], 5 vols., 6th ed. -

Olga Katsiardi-Hering, Ikaros Madouvalos the Tolerant Policy Of

Olga Katsiardi-Hering, Ikaros Madouvalos The Tolerant Policy of the Habsburg Authorities towards the Orthodox People from South-Eastern Europe and the Formation of National Identities (18th-early 19th Century) The modern concept of tolerance is a result of the Age of En- lightenment.1 Although the problem of how to deal with the ‘Other’ was by no means new –after all, Greeks, Jews, Christians, heretics and Muslims had found ways to coexist in antiquity, the Roman era and the Middle Ages– it was inherited by the Enlightenment as a set of critical issues specifically rooted in the tumultuous history of the early modern era. A crucial group of terms interwoven with the salient forms of collective identification, are those relating to mi- gration in the framework of multi-ethnic states (such as the Otto- man and Habsburg Empires): identity (religious, social, political, ethnic, national), naturalization, migration and diaspora. The real aim of our paper is to shed light on the developing na- tional self-consciousness of Orthodox groups established in Habs- burg territories in the Central Europe of the eighteenth century. Note that these people came from an Empire, the Ottoman, in which they were organized into a millet system according to their religion; in this system the Sultan granted them, on certain condi- tions, the right to worship.2 The core problem, however, were the 1. The first version of this article was presented at the International Congress of Europeanists in Amsterdam, June 2013. We would like to thank the NGUA of the University of Athens and the Special Account for Research Grants of the Democritus Univeristy of Thrace for supporting this research. -

Történelmi Szemle 58. Évf. 3. Sz. (2016.)

2016 3 ... A MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA ti BÖLCSÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KUTATÓKÖZPONT TÖRTÉNETTUDOMÁNYI INTÉZETÉNEK ÉRTESÍTŐJE A TARTALOMBÓL • B. SZABÓJANOS ÁRPÁD HONFOGLALÓINAK 9-l O. SZÁZADI HATALMISZERVEZETE ~ • SUDAR BALAZS A ZSARNÓCAI CSATA (!664) - TÖRÖK SZEMMEL ... • MIHALIK BÉLA VILMOS A SZENTSZÉK ÉS A MAGYAR VÁLASZTÓFEJEDELEMSÉG GONDOLATA • TÓTH FERENC EGY FELVILÁGOSULT URALKODÓ GONDOLATAI A FELVILÁGOSODÁS ELŐTT • ABLONCZY BALAZS BARÁ TH TIBOR PÁRIZSI ÉVEI ( 1930-1939) • HORVATH GERGELY KRISZTÜN SZEMPONTOK A KÉT VILÁGHÁBORÚ • KÖZÖTTI FALUKUTATÓK VIZSGÁLATÁHOZ • TÖRTÉNELMI SZEMLE A MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA BÖLCSÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KUTATÓKÖZPONT TÖRTÉNETTUDOMÁNYI INTÉZETÉNEK ÉRTESÍTŐJE LVIII. ÉVFOLYAM, 2016. 3. SZÁM Szerkesztők TRINGLI ISTVÁN (felelős szerkesztő) FÓNAGY ZOLTÁN, OBORNI TERÉZ, PÓTÓ JÁNOS, ZSOLDOS ATTILA (rovatvezetők) GLÜCK LÁSZLÓ (szerkesztőségi munkatárs) Szerkesztőbizottság FODOR PÁL (elnök), BORHI LÁSZLÓ, ERDŐDY GÁBOR, GLATZ FERENC, MOLNÁR ANTAL, ORMOS MÁRIA, OROSZ ISTVÁN, PÁLFFY GÉZA, PÓK ATTILA, SOLYMOSI LÁSZLÓ, SZAKÁLY SÁNDOR, SZÁSZ ZOLTÁN, VARGA ZSUZSANNA A szerkesztőség elektromos postája: [email protected] TARTALOMJEGYZÉK TANULMÁNYOK B. Szabó János: Árpád honfoglalóinak 9–10. századi hatalmi szervezete steppetörténeti párhuzamok tükrében 355 Mihalik Béla Vilmos: A Szentszék és a magyar választófejedelemség gondolata a 17. század végén 383 Tóth Ferenc: Egy felvilágosult uralkodó gondolatai a felvilágosodás előtt. Lotaringiai Károly herceg Politikai testamentuma, a magyar történelem elfelejtett forrása 409 Ablonczy -

King St Ladislas, Chronicles, Legends and Miracles

Saeculum Christianum t. XXV (2018), s. 140-163 LÁSZLó VESZPRÉMY Budapest KING ST LADISLAS, CHRONICLES, LEGENDS AND mIRACLES The pillars of Hungarian state authority had crystallized at the end of the twelfth century, namely, the cult of the Hungarian saint kings (Stephen, Ladislas and Prince Emeric), especially that of the apostolic king Stephen who organized the Church and state. His cult, traditions, and relics played a crucial role in the development of the Hungarian coronation ritual and rules. The cult of the three kings was canonized on the pattern of the veneration of the three magi in Cologne from the thirteenth century, and it was their legends that came to be included in the Hungarian appendix of the Legenda Aurea1. A spectacular stage in this process was the foundation of the Hungarian chapel by Louis I of Anjou in Aachen in 1367, while relics of the Hungarian royal saints were distributed to the major shrines of pilgrimage in Europe (Rome, Cologne, Bari, etc.). Together with the surviving treasures, they were supplied with liturgical books which acquainted the non-Hungarians with Hungarian history in the special and local interpretation. In Hungary, the national and political implications of the legends of kings contributed to the representation of royal authority and national pride. Various information on King Ladislas (reigned 1077–1095) is available in the chronicles, legends, liturgical lections and prayers2. In some cases, the same motifs occur in all three types of sources. For instance, as to the etymology of the saint’s name, the sources cite a rare Greek rhetorical concept (per peragogen), which was first incorporated in the Chronicle, as the context reveals, and later transferred into the Legend and the liturgical lections. -

Történelmi Szemle

TÖRTÉNELMI SZEMLE A MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA BÖLCSÉSZETTUDOMÁNYI KUTATÓKÖZPONT TÖRTÉNETTUDOMÁNYI INTÉZETÉNEK ÉRTESÍTŐJE LVIII. ÉVFOLYAM, 2016. 3. SZÁM Szerkesztők TRINGLI ISTVÁN (felelős szerkesztő) FÓNAGY ZOLTÁN, OBORNI TERÉZ, PÓTÓ JÁNOS, ZSOLDOS ATTILA (rovatvezetők) GLÜCK LÁSZLÓ (szerkesztőségi munkatárs) Szerkesztőbizottság FODOR PÁL (elnök), BORHI LÁSZLÓ, ERDŐDY GÁBOR, GLATZ FERENC, MOLNÁR ANTAL, ORMOS MÁRIA, OROSZ ISTVÁN, PÁLFFY GÉZA, PÓK ATTILA, SOLYMOSI LÁSZLÓ, SZAKÁLY SÁNDOR, SZÁSZ ZOLTÁN, VARGA ZSUZSANNA A szerkesztőség elektromos postája: [email protected] TARTALOMJEGYZÉK TANULMÁNYOK B. Szabó János: Árpád honfoglalóinak 9–10. századi hatalmi szervezete steppetörténeti párhuzamok tükrében 355 Mihalik Béla Vilmos: A Szentszék és a magyar választófejedelemség gondolata a 17. század végén 383 Tóth Ferenc: Egy felvilágosult uralkodó gondolatai a felvilágosodás előtt. Lotaringiai Károly herceg Politikai testamentuma, a magyar történelem elfelejtett forrása 409 Ablonczy Balázs: Ördögszekéren. Baráth Tibor párizsi évei (1930–1939) 429 Horváth Gergely Krisztián: Műhelyek, pályák, módszerek. Szempontok a két világháború közötti falukutatók vizsgálatához 451 MŰHELY Pósán László: A Német Lovagrend megítélése Magyarországon II. András korában 465 Sudár Balázs: A zsarnócai csata (1664) – török szemmel 475 DOKUMENTUM Jakó Zsigmond műhelyéből (Sajtó alá rendezte: Jakó Klára) 483 MÉRLEG Szigetvár, 1566. Konferenciabeszámoló (Kármán Gábor) 493 CONTENTS STUDIES János B. Szabó: The Structure of Power of the Hungarians in the 9th and 10th Centuries in the Mirror of Historical Analogies from the Steppe 355 Béla Vilmos Mihalik: The Holy See and the Idea of a Hungarian Electorate in the Late 17th Century 383 Ferenc Tóth: The Thoughts of an Enlightened Ruler before the Enlightenment. The Political Testament of Duke Charles of Lorraine, a Forgotten Source of Hungarian History 409 Balázs Ablonczy: On the Tumbleweed. -

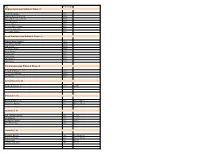

Name Generation Third Generation from William R. Wilson, Jr. Deirdre D Griffith 20-3+ Romulus Riggs Griffith VI 20-3+ Dorsey

Name Generation Third Generation from William R. Wilson, Jr. Deirdre D Griffith 20-3+ Romulus Riggs Griffith VI 20-3+ Dorsey Meriweather Griffith 20-3+ Lesley Alsentzer 20-3+ Michele Alsentzer 20-3+ Benjamin Harry Collins 20-3+ Laura Cecelia Collins 20-3+ Erin Louise Wilson 20-3+ Second Generation from William R. Wilson, Jr. Romulus Riggs Griffith V 20-2+ Sarah Wilson Griffith 20-2+ Ruth Wilson 20-2+ Eric Daniel Wilson 20-2+ Karen Quinn 20-2+ Kathy Quinn 20-2+ Cindi Quinn 20-2+ Jeffrey Quinn 20-2+ Sean Quinn 20-2+ First Generation from William R. Wilson, Jr. Evelyn Fell Wilson 20-1+ Harry Tinney Wilson 20-1+ Jane Wilson 20-1+ Starting Generation (1) William R. Wilson, Jr 19-0 TZ-338 Generation 1 (2) William R. Wilson, Sr. 19-1 TZ-338; HIJ-217 Adelaide L. Hyland 19-1 HIJ-217; TZ-338 Generation 2 (4) John Alexander Wilson 19-2 TZ-338 Sabella Baker 19-2 TZ-338 Washington Hyland 19-2 HIJ-217 Anna Eliza Ellis 19-2 HIJ-217 Generation 3 (4) Alexander Wilson 18-3 TZ-338; HIJ-211 Mary Ann Hyland 18-3 HIJ-211; TZ-338 Jacob Hyland 18-3 HIJ-217 Elizabeth Thackery 18-3 HIJ-217 Generation 4 (4) Edward Hyland 18-4 HIJ-210; A-171 Julia Arrants 18-4 A-171; HIJ-210 Stephen Hyland 18-4 HIJ-216; HIJ-50 Araminta Hamm 18-4 HIJ-50; HIJ-216 Generation 5 (8) John Hyland 18-5 HIJ-210 Mary Juliustra/Johnson 18-5 HIJ-210 Johannes Arrants 18-5 A-171; TZ-153 Elizabeth Veazey 18-5 TZ-153; A-171 John Hyland 18-5 HIJ-210; HIJ-216; TZ-35 Martha Tilden 18-5 TZ-35; HIJ-216 Thomas Hamm 18-5 HIJ-50; TZ-15 Ann Thompson 18-5 TZ-15; HIJ-50 Generation 6 (12) Nicholas Hyland, Jr. -

Twenty-Ninth Generation Those of England and of Ireland

Twenty-ninth Generation those of England and of Ireland. It became attached to him because the chronicler Fordun called him the "Lion of Justice". Due to the terms of the Treaty of Falaise, Henry II had the right to choose William's bride. As a result, William married Ermengarde de Beaumont, a granddaughter of King Henry I of England, at Woodstock Palace in 1186. Edinburgh Castle was her dowry. The marriage was not very successful, and it was many years before she bore him an heir. King William I "The Lyon" of Scotland and Ermengarde had the following children: 1. Margaret (1193–1259), married Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent. 2. Isabella (1195–1253), married Roger Bigod, 4th Earl of Norfolk. 3. Alexander II of Scotland (1198–1249). 4. Marjorie (1200–44), married Gilbert Marshal, 4th Earl of Pembroke. William died in Stirling in 1214 and lies buried in Arbroath Abbey. His son, Alexander II, succeeded him as king, reigning from 1214 to 1250. King William I "The Lion" of Scotland (Earl Henry of Huntingdon30, Saint David I of Scotland31_) was born 1143. King of Scotland (1165-1214). He succeeded his brother Malcolm IV. He attended Henry II of England in his Continental wars, and is supposed, while doing so, to have pressed for a portion at least of the long disputed districts of Northumberland, and other territories of what is now the north of England. In 1168 he made an alliance with France. This is the first recorded alliance between Scotland and that kingdom. In 1173 he conspired with the sons of Henry II against their father, and invaded Northumberland. -

Vol. 18 2013 Vol. 18 2013 KINGS IN

www.vistulana.pl 2013 www.qman.com.pl 18 vol. vol. vol. 18 2013 KINGS IN CAPTIVITY MACROECONOMY: ECONOMIC GROWTH ISBN 978-83-61033-69-1 KINGS IN CAPTIVITY MACROECONOMY: ECONOMIC GROWTH Fundacja Centrum Badań Historycznych Warszawa 2013 QUAESTIONES MEDII AEVI NOVAE Journal edited by Wojciech Fałkowski (Warsaw) – Editor in Chief Marek Derwich (Wrocław) Tomasz Jasiński (Poznań) Krzysztof Ożóg (Cracow) Andrzej Radzimiński (Toruń) Paweł Derecki (Warsaw) – Assistant Editor Editorial Board Gerd Althoff (Münster) Philippe Buc (Wien) Patrick Geary (Princeton) Andrey Karpov (Moscow) Rosamond McKit erick (Cambridge) Yves Sassier (Paris) Journal accepted in the ERIH and Index Copernicus lists. Articles, Notes and Books for Review shoud be sent to: Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae, Instytut Historyczny Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego; Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, PL 00-927 Warszawa; Tel./Fax: (0048 22) 826 19 88; [email protected] (Editor in Chief) Published and fi nanced by: • Institute of History of University of Warsaw • Nicolas Copernicus University in Toruń • Faculty of History of University of Poznań • Institute of History of Jagiellonian University of Cracow • Ministry of Science and Higher Education © Copyright by Center of Historical Research Foundation, 2013 ISSN 1427-4418 ISBN 978-83-61033-69-1 Printed in Poland Subscriptions: Published in December. The annual subscriptions rate 2013 is: in Poland 38,00 zł; in Europe 32 EUR; in overseas countries 42 EUR Subscriptions orders shoud be addressed to: Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa Naukowego “Societas Vistulana” ul. Garczyńskiego 10/2, PL 31-524 Kraków; E-mail: [email protected]; www.vistulana.pl Account: Deutsche Bank 24 SA, O/Kraków, pl. Szczepański 5 55 1910 1048 4003 0092 1121 0002 Impression 550 spec.