15 Archaeological Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stjosephsclonsilla.Ie

stjosephsclonsilla.ie A NEW STANDARD OF LIVING WELCOME TO Following on a long tradition of establishing marquee developments WELCOME TO in the Dublin 15 area, Castlethorn are proud to bring their latest creation St Josephs Clonsilla to the market. Comprising a varying mix of 2, 3 and 4 bed homes and featuring a mixture of elegant red brick and render exteriors, the homes provide a variety of internal designs, all of which are built with requirements necessary for todays modern living in mind. Designed by DDA Architects, all homes at St Josephs have thoughtfully laid out interiors, including spacious living rooms, fully fitted kitchens with integrated appliances, while upstairs well proportioned bedrooms with all 3 and 4 bedroom houses benefiting from ensuites. In addition, all homes will have an A3 BER energy rating ensuring that the houses will benefit from reduced energy bills and increased comfort. Superbly located in Clonsilla, St Josephs is within easy reach of many schools, parks, shops and transport infrastructure including Clonsilla train station that adjoins the development. EXCELLENT AMENITIES RIGHT ON YOUR DOORSTEP Clonsilla is a thriving village that of- fers an array of amenities including shops, restaurants, schools and sports clubs making it an attractive Dublin suburb with excellent transport links. The Blanchardstown Centre provides a large retail, food and beverage offering as well as a cinema and numerous leisure facilities. Retailers include Penneys, Marks & Spencer and Debenhams. Local primary schools include Scoil Choilm, St. Mochtas and Hansfield Educate Together. At secondary level there is Coolmine Community School, Castleknock Community College, Mount Sackville and Castleknock College. -

PDF (Ballyfermot Drug Task Force

BBaallllyyffeerrmmoott DDrruugg TTaasskk FFoorrccee SSttrraatteeggiicc PPllaann 22000011 -- 22000022 CONTENTS Part I Introduction 3 Situation 1997 - 2000 4 Performance summary 6 Lessons Learned Task Force 10 Interagency collaboration 11 Projects 12 Networks and Links 15 Profile of Services 17 Young Peoples Services and Facilities Fund 17 Youth Services 18 City of Dublin Youth Service Board 18 Relevant Voluntary Sector Services 21 Community and Resource Centres 24 Addiction Services South Western Area Health Board 26 Dublin Corporation 29 FÁS 30 Garda Síochana 32 Probation and Welfare 33 Ballyfermot Partnership 34 Collaborative Areas 36 Part II Public Consultation Overview 40 Objectives, Expected Outcomes 41 Workshops content 42 Emerging Themes 46 Drug use trends 54 Drug treatment statistics 64 Area demographics 68 Part III Stakeholder analysis 71 Environmental scanning 72 SWOT 73 Health promotion model 74 Quality model 75 1 Strategy 2001 -2002 77 Summary Budget 83 Bidding Process 84 Strategy Implementation 86 Part IV Delivery and Monitoring of Plan 102 Performance Indicators 103 Appendix 114 Details of outcomes by strategy and NDST code Detailed demographic profile Submission to URBAN Figures and tables as they appear in the document Figure 1 Networks of key services in Ballyfermot linked to the Task Force 15 Figure 2 Networks of Drug Task Force Treatment & Rehabilitation 16 Projects Figure 3 Drug searches and charges 5 Figure 4 Ballyfermot Residents in Drug Treatment by DED 1996 - 1999 64 Table 1 Residents of Ballyfermot presenting to Drug Treatment Services 65 1996 - 1999 Table 2 Clients receiving treatment in local centres by DED numbers and 66 percentages Table 3 Residents of ERHA attending Drug Treatment Services 67 Demographic Profile Table 4 Residents of Ballyfermot are attending Drug Treatment Services 67 Demographic Profile Figure 5 Live Register Figures 69 2 PART I Overview, Performance, Lessons 3 Introduction In developing a revised strategic plan for the Ballyfermot area, we are required to review progress to date. -

PL29S.246098 Developmen

An Bord Pleanála Inspector’s Report Appeal Reference No: PL29S.246098 Development: The dismantling and deconstruction of the existing Telephone Exchange Building for its storage at the Inchicore Stores Building (within the curtilage of a Protected Structure) at Inchicore Rail Works, Inchicore. Planning Application Planning Authority: Dublin City Council Planning Authority Reg. Ref.: 3929/15 Applicant: Iarnród Éireann Planning Authority Decision: Refuse Permission Planning Appeal Appellant(s): Iarnród Éireann Type of Appeal: First Party Observers: None Date of Site Inspection: 4th of May 2016 Inspector: Angela Brereton PL29S.246098 An Bord Pleanála Page 1 of 12 1.0 SITE LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION The property is located and accessed in the Irish Rail yard at Inchicore. This is to the west of the residential area of Inchicore Terrace South and accessed via Inchicore Parade at the end of St. Patrick’s Terrace. The railway line runs to the north of the site. The Plans submitted show the small area of the building in the context of the other buildings within the Inchicore Works Compound and as shown on the land ownership map. While there are many older more historic buildings within the landholding, there are also some more recently built. The Iarnród Éireann site is fully operational and has a security gated entrance and on-site parking. This is a detached stone/timber/slate building and there are two main rooms with connecting hallway. This small building is now cordoned off with security barriers and does not appear to be operational. It is adjacent to a pond area which also provides a water supply in case of fire. -

Negotiating Ireland – Some Notes for Interns

Welcome to Ireland – General Notes for Interns (2015 – will be updated for 2016 in January 2016) Fergus Ryan These notes are designed to introduce you to Ireland and to address any questions you might have concerning practical aspects about your visit to Ireland. About Ireland Ireland is an island on the north- financial services. The official west coast of Europe, with a languages are English and Irish. population of approximately 6.3 While English is the main language million inhabitants. It is of communication, Irish is spoken on approximately 32,600 square miles, a daily basis in some parts of the 300 miles from the northern most west, while over half a million tip to the most southern, and inhabitants speak a language other approximately 175 miles across, than English or Irish at home. making it just a little under half the (Sources: CSO Census 2011, size of Oklahoma State. www.cso.ie) Politically, the island comprises two Northern Ireland comprises six legal entities. The Republic of counties in the northeast corner of Ireland, with 4.6 million the island. A jurisdiction within the inhabitants, makes up the bulk of the United Kingdom, it has just over 1.8 island. The State attained million people. It has its own power- independence from the UK in 1922, sharing parliament and government and became a Republic in 1949. The with significant devolved powers Republic of Ireland is a sovereign, and functions. Its capital and largest democratic republic, with its current city is Belfast. Northern Ireland is Constitution dating back to 1937. It politically divided along religious is a member of the European Union lines: 48% of those in Northern and the Council of Europe, but is Ireland are Protestant or were militarily non-aligned. -

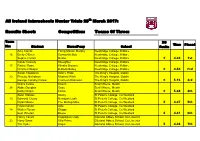

Teams of Three

All Ireland Interschools Hunter Trials 25th March 2017: Results Sheet: Competition: Teams Of Three: Team XC Time Placed No: Student Horse/Pony School Faults Amy Carroll Farrig Master Murphy Newbridge College, Kildare 16 Emily O'Brien Garnavilla Bob Newbridge College, Kildare Sophie Carroll Dexter Newbridge College, Kildare 0 4.34 1st Conor Cassidy Kiloughter Newbridge College, Kildare 17 Rachel Ross Kilnatic Brownie Newbridge College, Kildare Charlie O'Dwyer B-Boda Bailey Newbridge College, Kildare 0 4.54 2nd Sarah Fitzpatrick Odin's Pride The King's Hospital, Dublin 23 Phoebe Nicholson Mystical Wish The King's Hospital, Dublin George Conolly-Carew Coolteen Diamond The King's Hospital, Dublin 0 5.16 3rd Grace Evans Cooch Scoil Mhuire, Meath 36 Abbie Douglas Ozzie Scoil Mhuire, Meath Kathy Rispin Flicka Scoil Mhuire, Meath 0 5.38 4th Sean Stables Rocky St Peter's College, Co Wexford 13 Edmond Cleary Newtown Lash St Peter's College, Co Wexford Dylan Moore The Bishop Mike St Peter's College, Co Wexford 5 4.37 5th Frank Ronan Alfie St Peter's College, Co Wexford 14 Walter Ronan Skippy St Peter's College, Co Wexford Eoin Whelan Bosco St Peter's College, Co Wexford 5 4.41 6th Henry Farrell Cappaquin Lady Glenstal Abbey School, Co Limerick 33 Harry Swan Villa Prince Glenstal Abbey School, Co Limerick Tim Hyde Angel Glenstal Abbey School, Co Limerick 5 4.46 7th All Ireland Interschools Hunter Trials 25th March 2017: Results Sheet: Competition: Teams Of Three: Team XC Time Placed No: Student Horse/Pony School Faults Sarah Dunne Watson Gorey Community -

Inspector's Report ABP-306814-20

Inspector’s Report ABP-306814-20 Development Demolition of the existing single storey building (1,100 sq.m) last used as a motor business and its replacement with the construction of a 6 storey over basement hotel Location 30 Old Kilmainham, Kearns Place, Kilmainham, Dublin 8 Planning Authority Dublin City Council South Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 4623/19 Applicant(s) Ladas Property Company Unlimited Company (as part of Comer Group) Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Refuse Type of Appeal First Party Appellant(s) Ladas Property Company Unlimited Company (as part of Comer Group) Observer(s) 1. Adrian Muldoon 2. E. Lawlor 3. P. Lawlor ABP-306814-20 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 22 4. W & M Kinsella Date of Site Inspection 25th May 2020 Inspector Irené McCormack ABP-306814-20 Inspector’s Report Page 2 of 22 1.0 Site Location and Description The site is a corner site situated on the north side of Old Kilmainham Road. The site comprises a single storey industrial/warehouse building with a single storey reception/office to the front. There is surface car parking to the front and west of the site. The site was previously used as a garage and car sales but is now vacant. The area is characterised by a mixed form of urban development. The site is bound to the west by Kearns Place, which comprises two-storey terraced artisan type dwellings along its west side with a three storey Georgian type building on its western corner (with Old Kilmainham Road) opposite the site. Opposite the site on the south side of Old Kilmainham Road is an existing three-storey building office and warehouse. -

Central Statistics Office, Information Section, Skehard Road, Cork

Published by the Stationery Office, Dublin, Ireland. To be purchased from the: Central Statistics Office, Information Section, Skehard Road, Cork. Government Publications Sales Office, Sun Alliance House, Molesworth Street, Dublin 2, or through any bookseller. Prn 443. Price 15.00. July 2003. © Government of Ireland 2003 Material compiled and presented by Central Statistics Office. Reproduction is authorised, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. ISBN 0-7557-1507-1 3 Table of Contents General Details Page Introduction 5 Coverage of the Census 5 Conduct of the Census 5 Production of Results 5 Publication of Results 6 Maps Percentage change in the population of Electoral Divisions, 1996-2002 8 Population density of Electoral Divisions, 2002 9 Tables Table No. 1 Population of each Province, County and City and actual and percentage change, 1996-2002 13 2 Population of each Province and County as constituted at each census since 1841 14 3 Persons, males and females in the Aggregate Town and Aggregate Rural Areas of each Province, County and City and percentage of population in the Aggregate Town Area, 2002 19 4 Persons, males and females in each Regional Authority Area, showing those in the Aggregate Town and Aggregate Rural Areas and percentage of total population in towns of various sizes, 2002 20 5 Population of Towns ordered by County and size, 1996 and 2002 21 6 Population and area of each Province, County, City, urban area, rural area and Electoral Division, 1996 and 2002 58 7 Persons in each town of 1,500 population and over, distinguishing those within legally defined boundaries and in suburbs or environs, 1996 and 2002 119 8 Persons, males and females in each Constituency, as defined in the Electoral (Amendment) (No. -

Fingal CYPSC Children and Young People's Plan 2019-2021

Fingal Children and Young People’s Services Committee Fingal Children and Young People’s Plan 2019–2021 Contact Fingal Children and Young People’s Services Committee welcomes comments, views and opinions about our Children and Young People’s Plan. Copies of this plan are available at http://www.cypsc.ie. For further information or to comment on the plan, contact: Úna Caffrey Co-ordinator of FCYPSC Mail: [email protected] Tel: 01 870 8000 2 Map 1: Fingal County 3 Contents Contact .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Foreword ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Section 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 8 Background to Children and Young People’s Services Committees .................................................................... 9 Who we are ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Sub-group structure ........................................................................................................................................ -

Youth and Sport Development Services

Youth and Sport Development Services Socio-economic profile of area and an analysis of current provision 2018 A socio economic analysis of the six areas serviced by the DDLETB Youth Service and a detailed breakdown of the current provision. Contents Section 3: Socio-demographic Profile OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................... 7 General Health ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 Crime ......................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Deprivation Index ...................................................................................................................................................... 33 Educational attainment/Profile ................................................................................................................................. 38 Key findings from Socio Demographic Profile ........................................................................................................... 42 Socio-demographic Profile DDLETB by Areas an Overview ........................................................................................... 44 Demographic profile of young people ....................................................................................................................... 44 Pobal -

Download Brochure

These particulars are for guidance purposes only and do not form part of any contract or part thereafter. All descriptions, dimensions, references to condition and necessary permissions for use and occupation are given in good faith and should not be relied on as statement of fact. Any intending purchaser shall satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of them. No omissions, accidental error or misdescription shall be ground for a claim for compensation, nor for the recession of contract by either vendor or purchaser. The Staff at Brock Delappe are not authorised to make or give any representation or warranty in respect of this property. FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Oatlands, Castleknock, Dublin 15 €POA 21 Tyrconnell Road t: +353 (0)1 633 4446 Inchicore, Dublin 8 e: [email protected] Licence # 002179 w: www.brockdelappe.ie SuperValu SC, Main t: +353 (0)1 803 0750 St., Blanchardstown e: [email protected] Licence # 003199 w: www.allianceauctioneers.ie Oatlands is a superb new development comprising the restored 1790’s Oatlands House and 12 distinctively unique, modern homes. Oatlands is a superb new development comprising the internally with private gardens, communal courtyards and restored 1790’s Oatlands House and 12 distinctively unique meandering walkways through mature fruit gardens. houses in the adjoining restored stables and outbuildings to the north west of the main house. Oatlands is situated on and accessed directly from the Porterstown Road immediately adjacent to Castleknock Each house is completed to a high standard, which offers GAA grounds and approx. 400m from Castleknock Golf Club. -

IPA Journal Ireland December 2020

,3$ 6 ( 2 5 & 9 ( 2 ,. 0 3(5$ I RELAND WINTER 2020 www.ipaireland.org Issue 47 WORKING THROUGH LOCKDOWNNEC MEMBERS ADAPTING TO PANDEMIC ONLINE SHOPPING STAYING SAFE IN THE VIRTUAL RETAIL WORLD COLLECT THE TOYS TREASURED REMINDERS OF OUR CHILDHOOD THAT ARE IMPOSSIBLE TO GIVE AWAY THE LIFESTYLE & LEISURE MAGAZINE FOR IPA MEMBERS OF AN GARDA SÍOCHÁNA ST PAULS GCU A Christmas Message from St. Paul’s Garda Credit Union IJOURNAL PA IRELAND © IPA1974 28 Dear Members, e hope you are staying safe and well on the lead up to ECCU Health Insurance Form online with e-signature. Ensure you what will be a different Christmas for many of us. As upload all supporting documentation at the time of application Wyou make your preparations we would like to remind to avoid delays. you that St. Paul’s can offer you a Christmas Loan to help you meet any extra expense you may have at this time of year. You can of course call and speak to one of our friendly staff contentsWinter 2020 who can tailor a loan to suit your requirements and take your This may be the time for you to consider amalgamating any loan application over the phone at 021-4313355. other existing loans or credit card balances you may have APPRECIATION 6 President’s Diary into one St. Paul’s loan with a repayment schedule to suit your St. Paul’s free Online Account access has proved to be 13 Remembering IPA Member National and International budget. invaluable for our members during this pandemic and we John Munnelly, RIP meetings via Zoom recommend that, if you have not already registered, you do so 14 Darren Martin Christmas is a time for families and the ideal opportunity today via our website www.stpaulscu.ie for you to remind your family members that they too can COMPETITIONS Time to collect the toys benefit from all our loan rates and services. -

A History of the County Dublin; the People, Parishes and Antiquities from the Earliest Times to the Close of the Eighteenth Cent

A^ THE LIBRARY k OF ^ THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^ ^- "Cw, . ^ i^^^ft^-i' •-. > / • COUNTY ,r~7'H- O F XILDA Ji£ CO 17 N T r F W I C K L O \^ 1 c A HISTORY OF THE COUNTY DUBLIN THE PEOPLE, PARISHES AND ANTIQUITIES FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE CLOSE OF THE FIGIITKFXTH CENTURY. PART THIRD Beinsj- a History of that portion of the County comprised within the Parishes of TALLAGHT, CRUAGH, WHITEGHURCH, KILGOBBIN, KILTIERNAN, RATHMIGHAEL, OLD GONNAUGHT, SAGGART, RATHCOOLE. AND NEWGASTLE. BY FRANXIS ELRINGTON BALL. DUBLIN: Printed and Published hv Alex. Thom & Co. (Limited), Abbuv-st. 1905. :0 /> 3 PREFACE TO THE THIRD PART. To the readers who ha\c sliowii so ;^fiitifyiii^' an interest in flio progress of my history there is (hie an apolo^^y Tor the tinu; whieli has e]a|)se(l since, in the preface to the seroml pai't, a ho[)e was ex[)rcsse(l that a further Jiistalnient wouhl scjoii ap])eai-. l^lie postpononient of its pvil)lication has l)een caused hy the exceptional dil'licuhy of ohtaiiiin;^' inl'orniat ion of liis- torical interest as to tlie district of which it was j^roposed to treat, and even now it is not witliout hesitation that tliis [)art has heen sent to jiress. Its pages will he found to deal with a poidion of the metro- politan county in whitdi the population has heen at no time great, and in whi(di resid( ncc^s of ini])ortanc(> have always heen few\ Su(di annals of the district as exist relate in most cases to some of the saddest passages in Irish history, and tell of fire and sw^ord and of destruction and desolation.