1 Introduction: Remembering and Forgetting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Diversity in Politics and Public Life

BRIEFING PAPER CBP 01156, 22 October 2020 By Elise Uberoi and Ethnic diversity in politics Rebecca Lees and public life Contents: 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 2. Parliament 3. The Government and Cabinet 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 5. Public sector organisations www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Ethnic diversity in politics and public life Contents Summary 3 1. Ethnicity in the United Kingdom 6 1.1 Categorising ethnicity 6 1.2 The population of the United Kingdom 7 2. Parliament 8 2.1 The House of Commons 8 Since the 1980s 9 Ethnic minority women in the House of Commons 13 2.2 The House of Lords 14 2.3 International comparisons 16 3. The Government and Cabinet 17 4. Other elected bodies in the UK 19 4.1 Devolved legislatures 19 4.2 Local government and the Greater London Authority 19 5. Public sector organisations 21 5.1 Armed forces 21 5.2 Civil Service 23 5.3 National Health Service 24 5.4 Police 26 5.4 Justice 27 5.5 Prison officers 28 5.6 Teachers 29 5.7 Fire and Rescue Service 30 5.8 Social workers 31 5.9 Ministerial and public appointments 33 Annex 1: Standard ethnic classifications used in the UK 34 Cover page image copyright UK Youth Parliament 2015 by UK Parliament. Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 / image cropped 3 Commons Library Briefing, 22 October 2020 Summary This report focuses on the proportion of people from ethnic minority backgrounds in a range of public positions across the UK. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ ANGLO-SAUDI CULTURAL RELATIONS CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CONTEXT OF BILATERAL TIES, 1950- 2010 Alhargan, Haya Saleh Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 1 ANGLO-SAUDI CULTURAL RELATIONS: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES IN THE CONTEXT OF BILATERAL TIES, 1950-2010 by Haya Saleh AlHargan Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Middle East and Mediterranean Studies Programme King’s College University of London 2015 2 ABSTRACT This study investigates Anglo-Saudi cultural relations from 1950 to 2010, with the aim of greater understanding the nature of those relations, analysing the factors affecting them and examining their role in enhancing cultural relations between the two countries. -

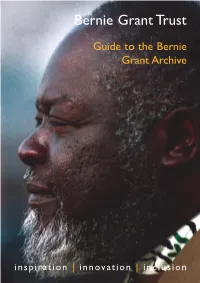

Guide to the Archive

Bernie Grant Trust Guide to the Bernie Grant Archive inspiration | innovation | inclusion Contents Compiled by Dr Lola Young OBE Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion . 4 Edited by Machel Bogues What’s in the Bernie Grant Archive? . 11 How it’s organised . 14 Index entries . 15 Tributes - 2000 . 16 What are Archives? . 17 Looking in the Archives . 17 Why Archives are Important . 18 What is the Value of the Bernie Grant Archive? . 18 How we set up the Bernie Grant Collection . 20 Thank you . 21 Related resources . 22 Useful terms . 24 About The Bernie Grant Trust . 26 Contacting the Bernie Grant Archive . 28 page | 3 Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion Born into a family of educationalists on London. The 4000 and overseas. He was 17 February 1944 in n 18 April 2000 people who attended a committed anti-racist Georgetown, Guyana, thousands of O the service at Alexandra activist who campaigned Bernie Grant was the people lined the streets Palace made this one of against apartheid South second of five children. of Haringey to follow the largest ever public Africa, against the A popular, sociable child the last journey of a tributes at a funeral of a victimisation of black at primary school, he charismatic political black person in Britain. people by the police won a scholarship to leader. Bernie Grant had in Britain and against St Stanislaus College, a been the Labour leader Bernie Grant gained racism in health services Jesuit boys’ secondary of Haringey Council a reputation for being and other public and school. Although he during the politically controversial because private institutions. -

On Parliamentary Representation)

House of Commons Speaker's Conference (on Parliamentary Representation) Session 2008–09 Volume II Written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 21 April 2009 HC 167 -II Published on 27 May 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Speaker’s Conference (on Parliamentary Representation) The Conference secretariat will be able to make individual submissions available in large print or Braille on request. The Conference secretariat can be contacted on 020 7219 0654 or [email protected] On 12 November 2008 the House of Commons agreed to establish a new committee, to be chaired by the Speaker, Rt. Hon. Michael Martin MP and known as the Speaker's Conference. The Conference has been asked to: "Consider, and make recommendations for rectifying, the disparity between the representation of women, ethnic minorities and disabled people in the House of Commons and their representation in the UK population at large". It may also agree to consider other associated matters. The Speaker's Conference has until the end of the Parliament to conduct its inquiries. Current membership Miss Anne Begg MP (Labour, Aberdeen South) (Vice-Chairman) Ms Diane Abbott MP (Labour, Hackney North & Stoke Newington) John Bercow MP (Conservative, Buckingham) Mr David Blunkett MP (Labour, Sheffield, Brightside) Angela Browning MP (Conservative, Tiverton & Honiton) Mr Ronnie Campbell MP (Labour, Blyth Valley) Mrs Ann Cryer MP (Labour, Keighley) Mr Parmjit Dhanda MP (Labour, Gloucester) Andrew George MP (Liberal Democrat, St Ives) Miss Julie Kirkbride MP (Conservative, Bromsgrove) Dr William McCrea MP (Democratic Unionist, South Antrim) David Maclean MP (Conservative, Penrith & The Border) Fiona Mactaggart MP (Labour, Slough) Mr Khalid Mahmood MP (Labour, Birmingham Perry Barr) Anne Main MP (Conservative, St Albans) Jo Swinson MP (Liberal Democrat, East Dunbartonshire) Mrs Betty Williams MP (Labour, Conwy) Publications The Reports and evidence of the Conference are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Race and Elections

Runnymede Perspectives Race and Elections Edited by Omar Khan and Kjartan Sveinsson Runnymede: Disclaimer This publication is part of the Runnymede Perspectives Intelligence for a series, the aim of which is to foment free and exploratory thinking on race, ethnicity and equality. The facts presented Multi-ethnic Britain and views expressed in this publication are, however, those of the individual authors and not necessariliy those of the Runnymede Trust. Runnymede is the UK’s leading independent thinktank on race equality ISBN: 978-1-909546-08-0 and race relations. Through high-quality research and thought leadership, we: Published by Runnymede in April 2015, this document is copyright © Runnymede 2015. Some rights reserved. • Identify barriers to race equality and good race Open access. Some rights reserved. relations; The Runnymede Trust wants to encourage the circulation of • Provide evidence to its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. support action for social The trust has an open access policy which enables anyone change; to access its content online without charge. Anyone can • Influence policy at all download, save, perform or distribute this work in any levels. format, including translation, without written permission. This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Licence Deed: Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales. Its main conditions are: • You are free to copy, distribute, display and perform the work; • You must give the original author credit; • You may not use this work for commercial purposes; • You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. You are welcome to ask Runnymede for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence. -

The Shaping of Black London

The Black London eMonograph series The Shaping of Black London By Thomas L Blair, editor and publisher The Black London eMonograph series is the first-ever continuous study of African and Caribbean peoples in the nation’s capital. Having published five eBooks, Prof Thomas L Blair is now at work delivering his research writings on Black people in London. He says: “Titles range from The Shaping of Black London to the first Black settlers in the 18th century to today’s denizens of the metropolis”. Also available Decades of research on race, city planning and policy provide a solid background for understanding issues in the public realm. Available from http://www.thomblair.org Thomas L Blair Collected Works/MONO (or search), they include: 1968 The Tiers Monde in the City: A study of the effects of Housing and Environment on Immigrant Workers and their Families in Stockwell, London, Department of Tropical Studies, the Architectural Association, School of Architecture, Bedford Square, London. 1972. http://www.thomblair.org.uk/The City Poverty Committee. To Make A Common Future. Notting Hill, London. Circa 1972 1978 PCL – Habitat Forum, Condition of England question. Papers and Proceedings. Edited by Dr Thomas L Blair, Professor of Social and Environmental Planning, Polytechnic of Central London, 1st volume in series 1978 1989. Information Base Report on Ethnic Minorities in London Docklands. Full Employ/LDDC Project. 1996. Area-based projects in districts of high immigrant concentration. By Thomas L Blair and Edward D Hulsbergen, Consultants. Community Relations, Directorate of Social and Economic Affairs, Council of Europe 1996. ISBN 92-871-3179-1. -

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020 Welcome to Memories on a Monday: Peace - sharing our heritage from Bruce Castle Museum & Archive. Following the commemorative events last week of VE Day, we turn now to looking at some of the ways we have marked peace in our communities in Haringey, alongside the strong heritage of the peace movement and activism in the borough. In July 2014, a memorial was unveiled alongside the woodland in Lordship Recreation Ground in Tottenham. Created by local sculptor Gary March, the sculpture shows two hands embracing a dove, the symbol of peace. Its design and installation followed a successful a campaign initiated by Ray Swain and the Friends of Lordship Rec to dedicate a permanent memorial to over 40 local people who tragically lost their lives in September 1940. They died following a direct hit by a high-explosive bomb falling on the Downhills public air raid shelter. It was the highest death toll in Tottenham during the Second World War. (You can see the sculpture and read more about this tragedy here and also here from the Summerhill Road website). Three years before, in Stroud Green, a Peace Garden was named and unveiled in 2011. It commemorates the 15 people who died, 35 people who were seriously injured, the destruction of 12 houses and the severe damage of Holy Trinity Church and 100 other homes in the area. The details below, can be read on the attached PDF. The Peace Garden Board can be found in the garden, at the junction where Stapleton Hall Road meets Granville Road, N4. -

Campaigning for the Labour Party but from The

Campaigning for the Labour Party but from the Outside and with Different Objectives: the Stance of the Socialist Party in the UK 2019 General Election Nicolas Sigoillot To cite this version: Nicolas Sigoillot. Campaigning for the Labour Party but from the Outside and with Different Ob- jectives: the Stance of the Socialist Party in the UK 2019 General Election. Revue française de civilisation britannique, CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d’études en civilisation britannique, 2020, XXV (3), 10.4000/rfcb.5873. hal-03250124 HAL Id: hal-03250124 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03250124 Submitted on 4 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XXV-3 | 2020 "Get Brexit Done!" The 2019 General Elections in the UK Campaigning for the Labour Party but from the Outside and with Different Objectives: the Stance of the Socialist Party in the UK 2019 General Election Faire campagne pour le parti travailliste mais depuis l’extérieur et avec des objectifs différents: -

Appendix: “Ideology, Grandstanding, and Strategic Party Disloyalty in the British Parliament”

Appendix: \Ideology, Grandstanding, and Strategic Party Disloyalty in the British Parliament" August 8, 2017 Appendix Table of Contents • Appendix A: Wordscores Estimation of Ideology • Appendix B: MP Membership in Ideological Groups • Appendix C: Rebellion on Different Types of Divisions • Appendix D: Models of Rebellion on Government Sponsored Bills Only • Appendix E: Differences in Labour Party Rebellion Following Leadership Change • Appendix F: List of Party Switchers • Appendix G: Discussion of Empirical Model Appendix A: Wordscores Estimation of Ideology This Appendix describes our method for ideologically scaling British MPs using their speeches on the welfare state, which were originally produced for a separate study on welfare reform (O'Grady, 2017). We cover (i) data collection, (ii) estimation, (iii) raw results, and (iv) validity checks. The resulting scales turn out to be highly valid, and provide an excellent guide to MPs' ideologies using data that is completely separate to the voting data that forms the bulk of the evidence in our paper. A1: Collection of Speech Data Speeches come from an original collection of every speech made about issues related to welfare in the House of Commons from 1987-2007, covering the period over which the Labour party moved 1 to the center under Tony Blair, adopted and enacted policies of welfare reform, and won office at the expense of the Conservatives. Restricting the speeches to a single issue area is useful for estimating ideologies because with multiple topics there is a danger of conflating genuine extremism (a tendency to speak in extreme ways) with a tendency or requirement to talk a lot about topics that are relatively extreme to begin with (Lauderdale and Herzog, 2016). -

Pdf, 511.2 Kb

IN THE UNDERCOVER POLICING INQUIRY OPENING SUBMISSIONS ON BEHALF OF CORE PARTICIPANTS SET OUT IN AN ANNEX REPRESENTED BY HODGE JONES & ALLEN, BHATT MURPHY AND BINDMANS SOLICITORS INTRODUCTION 1. This opening statement is made on behalf of over 100 individuals and groups, all of whom are Core Participants in this Inquiry. 2. All of them were subjected to undercover police surveillance that was inappropriate, improperly regulated, and abused their rights. They want answers from this Inquiry and ask that this Inquiry makes recommendations that prevent this experience happening to others. 3. These Core Participants come from a wide variety of backgrounds, ages, ethnicities and political views. But they all share an outrage at the experience each of them suffered. They deserve answers for the experiences they suffered through undercover policing to which none of them should have been subjected. Those officers and their supervisors, who committed that wrongdoing must be called to account, as must be the system that permitted it. 4. The experiences of these Core Participants spans more than a 40 year period from 1968 to the present date. They are people who campaigned – and still campaign – on a variety of different issues. Some have remained community activists, others have continued to seek justice for family members who were killed. Others have become senior political figures – including Members of Parliament, and a member of the House of Lords who is also a former Secretary of State. 5. A common feature that unites their experience is that the police surveillance to which they were subjected was not merely out of control, but was politicised. -

List of Haringey Dance Groups

Organisation Activity Venue Time Cost Contact Aniko's Dance Ballet, Tap, Modern Bernie Grant Tues & Thurs 4- Please check Contact: Aniko's Dance Academy Academy Theatre and Progressing Arts Centre 7pm & Sat 9am- with Email: [email protected] Ballet Technique classes 1pm organiser Tel: 020 8365 5450 Mob: 07789 605 166 Hornsey Vale Wednesdays 4- Website: www.AnikosDanceAcademy.co.uk; www.DancersHealth.com Community 6pm Centre Anita ballet Ballet Tottenham Wednesday 5pm – Please check Contact: Tottenham Community Sports Centre Community 6pm Tues & Weds centre Tel: 0208 801 6401 Afro -Caribbean Afro Caribbean Adults Sports Email: [email protected]; Centre, 701 Website: http://www.tottenhamsports.co.uk High Road, N17 7AD Bruce Grove Street Dance Bruce Grove Thursday 4pm to Please check Contact: Akin Youth Centre Youth Centre 6pm with Tel: 0802 489 5016 10 Bruce organiser Mob:07870 157 613 Grove Email:[email protected];[email protected]; Tottenham Website: www.youthspace.haringey.gov.uk N17 6RA Creative Dance Forget the idea "I can't Tottenham Wednesdays, £2:00 Contact: Elizabeth Arifien 60+ dance". This is a Green Pools 10am-11.30am Suggested Mob: 07773 683 711 movement class, with and Fitness, 1 donation Email: [email protected] Visceral Creative creative and Philip Facebook - @creativedance60 imaginative exercises Lane, N15 4JA that will allow you to Instagram - @creativedance60 explore your natural flow. Community Hub Bollywood Dance 8 Caxton Road, Tuesday 5:30 to £7.00 Contact: The Community HUB – Haringey Wood Green, 6:30 Tel - 0208 889 6938. Dance London N22 Email: [email protected] 6TB Weds 11pm to £3.00 Website: http://thecommunityhub.org.uk/ 12pm 1 Damn Fine Dance An innovative older Wednesdays Fees per Contact: Molly Wright people’s contemporary Jacksons Lane term: Tel: 07951 818 686 Rehearsals as dance company for 269A Archway £65 for a 6- Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; required. -

The Long, Slow Race Towards Greater Bame Labour Representation

THE LONG, SLOW RACE TOWARDS GREATER BAME LABOUR REPRESENTATION © Can Stock Photo / dolimac BY NADINE GRANDISON-MILLS 31/10/2017 Have you felt the shift? I certainly have. Since the rise and rise of Jeremy Corbyn, Labour’s ranks have swelled in numbers. Our party now boasts over half a million members (no small feat!) and is the largest political party in Western Europe. The sense of excitement is palpable. Active membership has increased, and even the younger generation (you know, that important group once considered as electorally unreliable) is finding their passion for politics. Overall, things seem truly wonderful! So, viewing things with my BAME Labour tinted spectacles, am I naturally filled with the same sense of elation? Err…well… Not quite. To be honest, my enthusiasm here is somewhat dented. At present there is no stunning vista to gaze at, though the optimist and activist in me still holds faith that one day there could be. Right now, rather, the view is misty and bleak with a faint ray of sunshine. Progress towards full BAME representation at all levels of the Labour Party (although always welcome!) has been at a painfully plodding pace, a bit like the tortoise from the Hare and Tortoise at the beginning of the story. Only this poor unfortunate creature is facing a daunting obstacle course. Uphill. Don’t get me wrong, the tortoise has covered quite a distance since the starting gun was fired. We have come quite a way since the historic 1987 elections, where the struggle for Black representation succeeded with Diane Abbott, Paul Boateng, Keith Vaz and the late Bernie Grant becoming the first Black Labour MPs.