The Islamic Movement in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andy Kim Touted Himself As President Obama's “Point Man”

HIT: Andy Kim touted himself as President Obama’s “point man” on Iraq issues at the White House. While working for the Obama administration, he attended meetings with terrorists including one of the leaders responsible for an attack at the US Embassy in Baghdad, and a senior member of the Muslim Brotherhood. BACKUP: Kim joined the State Department in 2009 as an Iraq expert: • Kim joined the State Department in 2009 as an Iraq expert. “Kim joined the Obama administration in September 2009 as an Iraq expert at the State Department. In 2011, he spent five months in Kabul in a civilian role advising two commanders of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, first Gen. David H. Petraeus and then Gen. John Allen.” (Salvador Rizzo, “Obama adviser running for Congress claims he also worked for Bush,” Washington Post, 9/10/18) Kim was the Iraq Director on Obama’s National Security Council from 2013 until leaving the administration in August 2015: • Kim was the Iraq Director on Obama’s National Security Council from 2013 until leaving the administration in August 2015. “Kim was director for Iraq issues at the Pentagon for five months in 2013 and then was Iraq director on Obama’s National Security Council for two years until leaving the administration in August 2015.” (Salvador Rizzo, “Obama adviser running for Congress claims he also worked for Bush,” Washington Post, 9/10/18) Kim was Obama’s “point man” on Iraq issues while serving in the National Security Council, a credential he has boasted about on the campaign trail: • The Flat Hat: “Kim served at the White House between 2013 and 2015 as Director of Iraq, where he was responsible for managing the crisis response across the Administration and developing strategy.” (Emily Martell, “Andrew Kim Discusses ISIS, Future Of Conflict In Iraq,” The Flat Hat, 11/10/16) • Kim noted he was the Obama Administration’s point man in 2014 as ISIS was gaining ground in Iraq. -

Draft Minutes

EU-TURKEY JOINT PARLAMENTARY COMMITTEE 74th Meeting 10-11 April 2014 European Parliament Brussels DRAFT MINUTES Thursday, 10 April 09.00 -12.30 Ms Hélène FLAUTRE, Co-Chair of the EU-Turkey Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) in the Chair Opening remarks The meeting opened on Thursday, 10 April 2014 at 9.00, with Ms Hélène FLAUTRE, Co-Chair of the European Union-Turkey Joint Parliamentary Committee (EU- Turkey JPC) in the Chair. Ms FLAUTRE welcomed the participants of the meeting and made a short introduction on the latest developments in the EU-Turkey relations, drawing particular attention to widespread concerns in the European Parliament (EP) about the directions the Turkish Government was taking and its attitude towards the European norms in the democratisation process. Following this short introduction Ms FLAUTRE gave the floor to Mr Afif DEMIRKIRAN, Co-Chair of the EU-Turkey Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) who made his opening remarks and expressed his optimism that relations between the two parliaments will be no less constructive and could be even strengthened in the next legislature. 1. Adoption of the draft agenda. It was agreed to start with the first working session and to discuss the draft agenda after the presentations on the EU-Turkey relations. 2. EU-Turkey relations and the state of play of the accession negotiations Mr Stefan FÜLE, European Commissioner for Enlargement started his intervention by emphasising that the timing was perfect for an exchange of views on this subject. The Commissioner noted a renewed momentum in the EU-Turkey relations (opening of Chapter 22, signing of the readmission agreement and developments in the dialogue on visa liberalisation, enhanced energy cooperation, trade relations and the strategic dialogue and cooperation in foreign policy), which lasted until the end of 2013. -

Erdogan's Islamist Foreign Policy at the Crossroads Kushal Agrawal

MP-IDSA Issue Brief Erdogan's Islamist Foreign Policy at the Crossroads Kushal Agrawal March 17, 2021 Summary Even as he continues to work towards reviving the Ottoman glory and 'Ittihad-I Islam' ('Unity of Islam'), there are significant limitations and vulnerabilities in Erdogan pursuing his Islamist approach to statecraft abroad. The Turkish President will have to choose between a pragmatic and an Islamist foreign policy. If the Turkish economy returns to high growth rates, Erdogan's domestic position will be strengthened and he might still return to his pet Islamist adventures overseas. ERDOGAN’S ISLAMIST FOREIGN POLICY AT THE CROSSROADS In his quest to become the leader of the Muslim world, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has in the recent past vehemently opposed the European Union (EU) governments as well as West Asian and North African countries for their policy positions on Islamic issues. Erdogan, for instance, went on an offensive against French President Emmanuel Macron for the latter’s perceived Islamophobic stance in the aftermath of beheading of Samuel Paty on October 16, 2020 in Paris. On October 24, 2020, Erdogan spoke against German authorities for raiding the Mevlana mosque in Berlin, closely associated with the Turkish Milli Gorus movement. Turkey’s relations with key Muslim countries like Saudi Arabia and Egypt have also been fraught, given Erdogan’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood. Since December 2020, however, Erdogan has been trying to reach out to the European Union and the West, in a possible effort to transform his pan-Islamist foreign policy outlook to a pro-Western Kemalist worldview. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

'Political Islam', and the Muslim Brotherhood Review

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee ‘Political Islam’, and the Muslim Brotherhood Review Sixth Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 1 November 2016 HC 118 Published on 7 November 2016 by authority of the House of Commons The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Crispin Blunt MP (Conservative, Reigate) (Chair) Mr John Baron MP (Conservative, Basildon and Billericay) Ann Clwyd MP (Labour, Cynon Valley) Mike Gapes MP (Labour (Co-op), Ilford South) Stephen Gethins MP (Scottish National Party, North East Fife) Mr Mark Hendrick MP (Labour (Co-op), Preston) Adam Holloway MP (Conservative, Gravesham) Daniel Kawczynski MP (Conservative, Shrewsbury and Atcham) Ian Murray MP (Labour, Edinburgh South) Andrew Rosindell MP (Conservative, Romford) Nadhim Zahawi MP (Conservative, Stratford-on-Avon) The following member was also a member of the Committee during this inquiry: Yasmin Qureshi MP (Labour, Bolton South East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/facom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry page of the Committee’s website. -

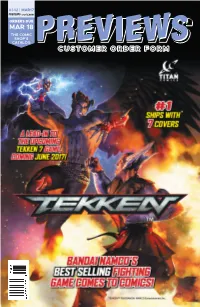

MAR17 World.Com PREVIEWS

#342 | MAR17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE MAR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Mar17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 1:36:31 PM Mar17 C2 DH - Buffy.indd 1 2/8/2017 4:27:55 PM REGRESSION #1 PREDATOR: IMAGE COMICS HUNTERS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUG! THE ADVENTURES OF FORAGER #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT/ YOUNG ANIMAL JOE GOLEM: YOUNGBLOOD #1 OCCULT DETECTIVE— IMAGE COMICS THE OUTER DARK #1 DARK HORSE IDW’S FUNKO UNIVERSE MONTH EVENT IDW ENTERTAINMENT ALL-NEW GUARDIANS TITANS #11 OF THE GALAXY #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Mar17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/9/2017 9:13:17 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Hero Cats: Midnight Over Steller City Volume 2 #1 G ACTION LAB ENTERTAINMENT Stargate Universe: Back To Destiny #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Casper the Friendly Ghost #1 G AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Providence Act 2 Limited HC G AVATAR PRESS INC Victor LaValle’s Destroyer #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS Misfi t City #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Swordquest #0 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT James Bond: Service Special G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Spill Zone Volume 1 HC G :01 FIRST SECOND Catalyst Prime: Noble #1 G LION FORGE The Damned #1 G ONI PRESS INC. 1 Keyser Soze: Scorched Earth #1 G RED 5 COMICS Tekken #1 G TITAN COMICS Little Nightmares #1 G TITAN COMICS Disney Descendants Manga Volume 1 GN G TOKYOPOP Dragon Ball Super Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Line of Beauty: The Art of Wendy Pini HC G ART BOOKS Planet of the Apes: The Original Topps Trading Cards HC G COLLECTING AND COLLECTIBLES -

Saudi Arabia's Curriculum of Intolerance

2008 Update Saudi Arabia’s Curriculum of Intolerance With Excerpts from Saudi Ministry of Education Textbooks for Islamic Studies Center for Religious Freedom of the Hudson Institute 2008 WITH THE INSTITUTE FOR GULF AFFAIRS 2008 Update: Saudi Arabia’s Curriculum of Intolerance Center for Religious Freedom of Hudson Institute With the Institute for Gulf Affairs 2 Copyright © 2008 by Center for Religious Freedom Published by the Center for Religious Freedom Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the Center for Religious Freedom, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Center for Religious Freedom Hudson Institute 1015 15th Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20005 Phone: 202-974-2400 Fax: 202-974-2410 Website: http://crf.hudson.org 3 About the Center for Religious Freedom The Center for Religious Freedom promotes religious freedom as a component of U.S. foreign policy by working with a worldwide network of religious freedom experts to provide defenses against religious persecution and oppression. Since its inception in 1986, the Center has sponsored investigative field missions, reported on the religious persecution of individuals and groups abroad, and undertaken advocacy on their behalf in the media, Congress, State Department and White House. Religious freedom faces difficult new challenges. Recent decades have seen the rise of extreme interpretations of Islamist rule that are virulently intolerant of dissenting voices and other traditions within Islam, as well as other faiths. Many in the policy world still find religious freedom too "sensitive" to raise. -

The Terrorism Trap: the Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror John Akins University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Akins, John, "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by John Akins entitled "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Krista Wiegand, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Brandon Prins, Gary Uzonyi, Candace White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America’s War on Terror A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville John Harrison Akins August 2019 Copyright © 2019 by John Harrison Akins All rights reserved. -

Open PDF 260KB

Education Committee Oral evidence: Accountability hearings, HC 262 Tuesday 10 November 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 10 November 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Robert Halfon (Chair); Apsana Begum; Dawn Butler; Jonathan Gullis; Tom Hunt; Dr Caroline Johnson; Kim Johnson; David Johnston; Ian Mearns; David Simmonds; Christian Wakeford. Questions 417 - 515 Witnesses I: Amanda Spielman, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector, Ofsted; and Yvette Stanley, National Director, Regulation and Social Care, Ofsted. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Amanda Spielman and Yvette Stanley. Q417 Chair: Good morning, everyone. We are very pleased to have Ofsted here today addressing our Committee. For the benefit of the tape and those who are watching on the internet, could you kindly give your names and your position, and also if you are happy for us to address you with first names or whether you would like your full address. Amanda Spielman: I am very happy to be addressed by my first name. I am Amanda Spielman, and I am the Ofsted Chief Inspector. Yvette Stanley: Yvette Stanley, happy to be “Yvette”. I am the National Director for Regulation and Social Care at Ofsted. Q418 Chair: Thank you. Amanda, you published a report today. For the benefit of those watching, can you set out the key conclusions, as we have only heard what has been in the media? Amanda Spielman: We published a set of reports on early years, schools, further education, and children with special educational needs and disabilities. -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

The Allied Occupation of Germany Began 58

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Abdullah, A.D. (2011). The Iraqi Media Under the American Occupation: 2003 - 2008. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/11890/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CITY UNIVERSITY Department of Journalism D Journalism The Iraqi Media Under the American Occupation: 2003 - 2008 By Abdulrahman Dheyab Abdullah Submitted 2011 Contents Acknowledgments 7 Abstract 8 Scope of Study 10 Aims and Objectives 13 The Rationale 14 Research Questions 15 Methodology 15 Field Work 21 1. Chapter One: The American Psychological War on Iraq. 23 1.1. The Alliance’s Representation of Saddam as an 24 International Threat. 1.2. The Technique of Embedding Journalists. 26 1.3. The Use of Media as an Instrument of War.