Multilevel Access to Justice in a World of Vanishing Trials: a Conflict Resolution Erspectivp E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durchbruch Des Fundamentalismus? Ein Neues Gesicht Der Orthodoxie Im Judentum Ungarns

Larissza Hrotkó Durchbruch des Fundamentalismus? Ein neues Gesicht der Orthodoxie im Judentum Ungarns DEUTSCH ABSTRACT Am Beispiel des gegenwärtigen ungarischen Judentums behandelt dieser Beitrag den religiösen Fundamentalismus als eine moderne gesellschaft- liche und kulturelle Erscheinung. Theologisch gesehen kann der Funda- mentalismus auch als eine patriarchale Protestbewegung betrachtet wer- den, die die religiöse Tradition im Interesse der Machterhaltung miss- braucht. Die Orthodoxie nimmt im fundamentalistischen Konzept einen besonderen Platz ein. Sie kann sich manchmal den Verhältnissen und Bedürfnissen moderner europäischer Gesellschaften anpassen und ein frauenfreund liches, ja sogar demokratisches Gesicht zeigen. Diese Form der Ortho doxie wird im Artikel als Neo-Orthodoxie bezeichnet. Die De- mokratie in einer neo-orthodoxen Gemeinschaft ist aber nur eine schein- bare, denn die wirkliche Macht konzentriert sich bei den Rabbinern, die entscheiden, wieviel Freiheit den Mitgliedern der Gemeinschaft und ins- besondere den Frauen zugestanden wird. Zurzeit scheinen der Einfluss der jüdischen Neo-Orthodoxie und somit die Gefahr des Durchbruchs des Fun- damentalismus in Ungarn zu steigen. Die nicht-orthodoxen jüdischen Ge- meinschaften sind dagegen nicht aktiv genug und beschäftigen sich wenig mit der Stärkung ihrer eigenen jüdischen Identität. ENGLISH A fundamentalist revolution? The new face of Jewish Orthodoxy in Hungary This article examines religious fundamentalism as a modern societal and cul- tural phenomenon on the subject -

LEADING the WAY Returning

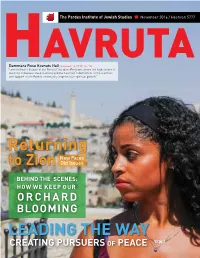

The Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies November 2016 / Heshvan 5777 AVRUTA HDammara Rose Kovnats Hall (Summer ’16, PCJE ’16-’19) “I am thrilled to be part of the Pardes Educators Program, where the high caliber of teaching stimulates deep learning and the heartfelt commitment of the teachers and support of the Pardes community inspires true spiritual growth.” Returning New Faces to Zion Old Issues BEHIND THE SCENES: HOW WE KEEP OUR ORCHARD BLOOMING LEADING THE WAY CREATING PURSUERS of PEACE Jewish learning know that these texts are rich, nuanced, Why Study and filled with thought-provoking ideas and arguments. Studying Bible, Mishna, Talmud and Jewish Thought often Torah? puts us up against the bigger questions of life. It takes us out of our routine concerns and daily decision-making, forcing us to confront questions of morality and meaning. As many of us know from our Pardes experience, it has the power to transform. Unlike superficial learning, there are any Jews see ancient no pat answers and we are often left with more questions texts as irrelevant to than answers. Yet we emerge fuller and richer for the Ma post-modern world. process. Antiquated. Misogynistic. Even immoral. And honestly, the classical texts of the Jewish tradition are very old, and The study of Torah also connects us with the genius often challenging to us, who seem to live in a very different of the Jewish people. It connects us to our ancestors, world. But is our world really so different? ancient, medieval, and modern, even if that connection is to disagree with them. -

In Landmark Ruling, El Al Ordered to End Policy of Asking Women to Move Seats | the Times of Israel 6/22/17, 1�53 PM

In landmark ruling, El Al ordered to end policy of asking women to move seats | The Times of Israel 6/22/17, 153 PM THE TIMES OF ISRAEL | www.timesofisrael.com In landmark ruling, El Al ordered to end policy of asking women to move seats Holocaust survivor Renee Rabinowitz wins suit against Israel’s national carrier over flight attendants’ request she change places after ultra- Orthodox man refused to sit beside her BY RAOUL WOOTLIFF June 22, 2017, 6:08 am srael’s national carrier, El Al, can no longer accede to the requests of ultra-Orthodox passengers not to sit next to women, a Jerusalem court said Wednesday in a landmark I ruling. “Under absolutely no circumstances can a crew member ask a passenger to move from their designated seat because the adjacent passenger doesn’t wasn’t to sit next to them due to their gender,” Jerusalem Magistrate’s Court Judge Dana Cohen-Lekah said in her ruling. “The policy is a direct transgression of the law preventing discrimination.” El Al has been known to regularly ask passengers to move seats at the request and sometimes demand of ultra-Orthodox men who refuse to sit next to women. Wednesday’s ruling ends years of uproar over the policy led by rights groups who say it is discriminatory. Cohen-Lekah agreed with the Israel Religious Action Center, which brought the suit, in ruling the practice was illegal. The chief plaintiff in the case was 81-year old Holocaust survivor Renee Rabinowitz, who sued the airline for discrimination after a flight attendant asked her to move seats on a flight in December 2015. -

O9 Donorreport

O9 DONOR REPORT PRESIDENT GEORGE CAMPBELL JR. ABOVE WITH: (l to r) State Assembly Member Deborah Glick, Vice President Robert Hawks, architect Thom Mayne, student Wallace Torres (Eng’11), President of New York City’s Economic Development Corporation Seth Pinsky, Vice President Ronni Denes, Alumni Association President MaryAnn Nichols (A’68), Professor Richard Stock, associate architects Peter Samton and Jordan Gruzen, construction manager Frank Sciame and Chair of the Board of Trustees, Ronald W. Drucker (CE’62) cutting the ribbon at 41 Cooper Square. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE THE COOPER UNION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE AND ART 2009 DONOR REPORT 1 Each year in The Cooper Union Donor Report, enthusiastic audience. Related to the Great we say thank you for the generosity and Evenings, in June we hosted Mayor Michael devotion to the college shown through Bloomberg and the leadership of the NAACP contributions by individuals, alumni, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the foundations and government. This year, on organization’s first meeting, which took place behalf of the Trustees, officers, staff, faculty in the Great Hall. and students, I would like to express an As we reflect on the past century and a especially profound and heartfelt gratitude half, we remain deeply focused on maintaining to all who supported our academic programs the absolute highest standards of academic and renewal of our facilities in the face of rigor that make our tuition-free education so extreme economic apprehension. highly coveted, exemplified by the soaring In spite of the financial uncertainties, in applications for admission. Our selectivity 2009, we began the celebration of the 150th is among the best in the nation, with an anniversary of the founding of The Cooper acceptance rate of only seven percent. -

Rabbi Bob Alper Is Coming to Temple Beth

A Monthly Publication for Temple Beth-El, Las Cruces, New Mexico AUGUST 2017 (AV-ELUL 5777) Shabbat Services (See Page 2) Rabbi Bob Alper Friday, August 4 is coming to Family Shabbat Service at 6 pm, (June, July & August Temple Beth-El! birthday blessings included) with a Potluck Dinner following Friday, August 25— Friday, August 11 ”The Spirituality of Shabbat Service at 7pm Friday, August 18 Laughter” presentation Shabbat Service for Renewal of Spirit at 7 pm during Shabbat Worship; Friday, August 25 Saturday night, August 26 at Shabbat Service at 7pm Friday, September 1-Special Schedule 7:30 pm—Stand-Up Comedy Wine (regular and non-alcoholic) and Cheese at 5:45 pm See Page 5 for Shabbat Service at 6:15 pm more information! Saturdays Talmud Study at 9:00 am, Be watching in early August Shabbat Service at 10:15 am, followed by a potluck Kiddush For High Holy Day mailings For parts for worship and the Rabbi Karol is presenting 2017/5778 Yizkor Booklet brief talks during the sum- ****************** mer on books that he hopes Religious School will begin with you will also be interested in exploring: a first morning orientation and gathering on Sunday, August 27 Tuesday, August 29 at 7:00 pm at 10:00-11:30 am. Praying the Bible: Finding Personal Parents will receive Meaning in the Siddur, Ending Boredom & Making Each Prayer Experience registration materials Unique, by Rabbi Mark H. Levin (Jewish during the first week of August! Lights Publishing). AUGUST 2017 (AV-ELUL 5777) Page 2 Worship Schedule Saturday, August 26 Please note: All 7:00 pm services will include either a Torah 9:00 am Talmud Study reading and a d’var torah, a brief discussion based on the To- 10:15 am Shabbat Morning Service & Potluck Kiddush rah portion, a compilation of prayers and/or songs on the Parashat Shoftim Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9 theme of the Torah portion, or a brief D’var Torah that offers Haftarah Isaiah 51:12-52:12 an insight based on the parashah for the week. -

Is It Permissible for Men and Women to Sit Next to Each Other on an Airplane?

Is it Permissible for Men and Women to Sit Next to Each Other on an Airplane? Byline: Rabbi Shimshon Nadel Page 1 by Rabbi Shimshon Nadel (the article first appeared in OU Israel's Torah Tidbits in hisweekly column, "Medina & Halacha."http://www.ttidbits.com/1282/1282rnadel.pdf) It was announced last week that El Al, Israel's national carrier, will remove any passenger who refuses to sit next to another passenger for any reason. The announcement comes following an incident just days prior, when a flight from New York to Israel was delayed by more than an hour after four religious men refused to sit in their assigned seats next to women. The story ‘went viral,’ and in response, a large tech company threatened to boycott the airline, prompting El Al's decision. In June 2017, just one year ago, a Jerusalem court ruled that airline employees cannot ask women to change seats after Renee Rabinowitz, a woman in her 80's, sued El Al for making her change her seat on a 2015 flight from Newark to Tel Aviv. Those of us who travel frequently are quite familiar with the following scene: Delayed departures as the cabin crew attempts to accommodate male passengers who refuse to sit next to women, claiming Jewish Law does not allow for it. But is it permissible for a man to sit next to a woman according to Jewish Law? It is prohibited for a man to touch a woman who is forbidden to him. In the context of forbidden relationships, the Torah instructs: “…Do not come close to uncovering Ervah” (Vayikra 18:6). -

Theyinnmagazine

בס׳׳ד THEYINNMagazine Rosh Hashanah 5781 שנה טובה Wishing All Congregants a Shana Tova e-mail: [email protected]. il Tel: 09-862-4824 The Choice of AACI Netanya For Excellence - Country wide B | YINN Rosh Hashanah 5781 THEYINNMagazine In This Edition Rosh Hashanah 5781 Letter from the Editor ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Yamim Noraim Message by Rabbi Boruch M. Boudilovsky ..........................................................................................................................................4 Nachas (Since Pesach 5780) ...............................................................................................................................................................................................6 Chairman’s Message by Graham Nussbaum ..................................................................................................................................................................7 Chatan Torah: Rabbi David Woolf .................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Chatan Bereshit: Ronnie Lawrence .................................................................................................................................................................................9 It’s Tradition by -

Israeli Scouts Friendship Caravan to Hold Community Performance On

June 30-July 6, 2017 Published by the Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton Volume XLVI, Number 26 BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK Israeli Scouts Friendship Caravan to hold community performance on July 27 By Lynette Errante Tzofim throughout Israel, only 100 are chosen The Israel Scouts will perform on Thurs- annually for the Tzofim Summer Delegation. day, July 27, at 7 pm, at the Jewish Com- The Tzofim Friendship Caravan travels munity Center, 500 Clubhouse Rd., Vestal. throughout North America, visiting summer Their performance will be followed by camps and cities. In representing Israel, the refreshments and a meet-and-greet with the Tzofim Friendship Caravan members use Scouts. The Scouts will spend the day with song and dance as their means of expression. the campers at Camp JCC playing traditional The Caravan features 10 teenagers and two Israeli games. The evening performance will adult leaders. be free to the community, but RSVPs will To become part of the Friendship Cara- be appreciated and can be made by calling van, the Tzofim must go through a four-tier the JCC office at 724-2417, ext. 110. elimination process. They are selected Founded in 1919, the Israel Scouts were on the basis of personal interviews, their the first Zionist youth movement in Israel knowledge of Israel, English communica- and the first egalitarian Scouting movement tion skills, general group interaction and in the world where boys and girls partic- leadership abilities. ipated together. The first delegation was After they are selected to be part of the sent to the United States in 1958. Today, Friendship Caravan, the Scouts rehearse the Israel Scouts, Tzofim, remain the only weekly for four months in Tel Aviv under the non-political youth movement in Israel and direction of entertainment professionals. -

The Impact of the Judicial Precedents on the Normative Content of Human Rights1

Pobrane z czasopisma Studia Iuridica Lublinensia http://studiaiuridica.umcs.pl Data: 26/09/2021 08:25:36 Part 1. Studia Iuridica Lublinensia vol. XXVII, 1, 2018 DOI: 10.17951/sil.2018.27.1.45 Tadeusz Biernat Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski Kraków University, Poland [email protected] The Impact of the Judicial Precedents on the Normative Content of Human Rights1 Wpływ precedensu na treść normatywną praw człowieka SUMMARY The major objective of this article is to emphasise the importance and the role of precedent – understood in broad terms – in forming the normative reality, exerting an impact on the content of normative elements, including human rights, particularly women’s rights. Being an essential part of the normative reality, precedents are a particular kind of normative messages of a considerable power. Taken into account their narrative form, comprehensiveness of the content, media hype and possibilities of a mass broadcasting, precedents constitute an important element and play a significant role in forming the normative reality, which is characteristic for the present-day society. Being a phe- nomenon characteristic for a post-modernist society, the normative reality is understood in contrast to static conceptions of a normative or axionormative order, which have a given structure and distinct boundaries. The analysis of precedent rulings, stemming from various law orders, regarding women’s equal rights in the employmentUMCS process, aims at highlighting their importance both in forming the content of human rights and their impact on law and law enactment. Keywords: precedent; normative approach; human rights; women’s rights The main aim of this article2 is to point out the role and the importance of widely understood precedents in shaping the normative space and its elements, among them human rights, and particularly women’s rights3. -

Theyinnmagazine

THEYINNMagazine Pesach 5781 Wishing All Congregants a Shana Tova e-mail: [email protected]. il Tel: 09-862-4824 The Choice of AACI Netanya For Excellence - Country wide B | YINN Pesach 5781 THEYINNMagazine Contents Pesach 5781 Letter from the Editor ........................................................ 3 After the Holocaust Greetings to our Grandchildren and Translation by Mr. Huub Stollman Great Grandchildren 2021 ................................................ 4 Submitted by Paula Edery ............................................... 20 A New Song Shtetl Uniontown by Rabbi Boruch M. Boudilovsky ....................................... 5 By Rabbi Arnie Fine ......................................................... 23 Chairman’s Message Israel’s Achilles’ Heel by Graham Nussbaum ....................................................... 6 by Raymond Cannon ....................................................... 27 LORD JONATHAN HENRY SACKS – 1948 TO 2020 Sixty Years Ago CHIEF RABBI 1991 TO 2013 By Sheila Levitt ............................................................... 28 by Elkan Levy .................................................................... 7 Ghetto Money Closure — A True Story by Ian Fine ...................................................................... 29 by Antonia Maurer Levy ..................................................... 9 Yummy in North Netanya Passover Poem ................................................................. 9 by The Recipe Team ........................................................ -

New Items – January 2016 Ebooks and Electronic Theses Are

New Items – January 2016 Ebooks and Electronic Theses are displayed as [electronic resource] Including books from previous years in special collections added to the Music Library Klein, Tzipi author. Dynamics and mechanisms of viral genetic variability [electronic resource] / Tzipi Klein. 2015 (002419481 ) Human genetics -- Variation. Bar Ilan University -- Dissertations -- Department of Life Sciences .אוניברסיטת בר-אילן -- עבודות לתאר שני -- הפקולטה למדעי החיים Smorodinsky, Serj Noam author. Digital pheromones : [electronic resource] chemomimetic self-organizing information / Serj Noam Smorodinsky. 2015 (002419482 ) Self-organizing systems. Bar Ilan University -- Dissertations -- Department of Life Sciences .עבודות לתאר שני -- הפקולטה למדעי החיים --אוניברסיטת בר-אילן Middle eastern politics [electronic resource] [London] : Routledge/Taylor & Francis, [date of publication not identified] (002419639 ) Middle East -- Politics and government. Castro, Boaz author. Dereverberation using multichannel blind system identification [electronic resource] / Boaz Castro. 2015 (002419873 ) System identification. Bar Ilan University -- Dissertations Faculty of Engineering .הפקולטה להנדסה -- אוניברסיטת בר אילן -- עבודות לתאר שני Kesner Baruch, Yael author. Little scientists [electronic resource] : emotional and cognitive aspects among teachers and children towards engaging in science in pre- school education / Yael Kesner Baruch. 2015 (002419875 ) Science -- Study and teaching (Early childhood) Bar Ilan University -- Dissertations School of Education -

Sexual Hostility a Mile High Michelle L.D

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 28 Article 4 Number 2 Summer 2017 Summer 2017 Sexual Hostility a Mile High Michelle L.D. Hanlon Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Michelle L.D. Hanlon, Sexual Hostility a Mile High, 28 Hastings Women's L.J. 181 (2017). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol28/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Hostility a Mile High Michelle L.D. Hanlon* I. INTRODUCTION On October 21, 2016, the United Nations designated “the character of Wonder Woman . as Honorary Ambassador for the Empowerment of Women and Girls.”1 The irony was not lost on United Nations staff who strenuously objected to the elevation and presumed adulation of a comic book character who is most commonly depicted as “a large breasted, white woman of impossible proportions, scantily clad in a shimmery, thigh-baring body suit with an American flag motif and knee high boots—the epitome of a ‘pin-up’ girl.”2 Sadly, it seems in the eyes of the global community, a fictitious caricature of a woman is more inspiring than, for example, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Hewlett-Packard Chief Executive Meg Whitman,3 any of the diverse group of sixty women who have flown in space, or, for that matter, a middle-class working woman like a flight attendant, who trains arduously to assure the safety of the flying public.