The Intertextual Stardom of Iris: Winslet, Dench, Murdoch, and Alzheimer's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nexus-2019-01.Pdf

2019.NEXUS 01 edita: Antonio Ballesteros � Percy John BYsshe Keats SheLLey POETRY 1819 WaLt WhitMAn IRIS NOVEL 1919 MURDOCHCONTENT& ESSAY LANGUAGE INTEGRATED ČLIL LEARNING � Presidente ALBERTO LÁZARO LAFUENTE Universidad de Alcalá Secretario ANTONIO BALLESTEROS GONZÁLEZ 2019.NEXUS 01 UNED Vocal 1a CRISTINA ALSINA RÍSQUEZ Copyright De los textos, sus autores. Universitat de Barcelona Editor ANTONIO BALLESTEROS GONZÁLEZ Vocal 2a ROSARIO ARIAS DOBLAS Universidad de Málaga Graphic TONI CAMPS design useixantaquatre.com Tesorera CRISTINA SUÁREZ GÓMEZ Universitat de les Illes Balears ISSN 1697-4646 http://www.aedean.org nexus 2019-01 ÍNDICE LITERATURE AND CULTURE AND LITERATURE TRIBUTES BILL PHILLIPS Universitat de Barcelona 8 Percy Bysshe Shelley & John Keats are Dead White European Men EULALIA PIÑERO GIL Universidad Autónoma de Madrid 15 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself Walt Whitman, el poeta de las emociones y los sentidos. MARIÁNGEL SOLÁNS GARCÍA Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia 25 Vida y posteridad de una mente brillante Iris Murdoch (1919-1999) LINGUISTICS ARTICLE XABIER SAN ISIDRO Moray House School of Education; University of Edinburgh 33 The Multi-faceted Effects of CLIL A Literature Review 3 nexus 2019-01 ÍNDICE LINGUISTICS PAPER RESEARCH JAVIER PÉREZ GUERRA Universidade de Vigo Linguistic variation all over 50 the place Some Briefing Notes about the LVTC Research Group BOOK REVIEWS VICENT BELTRÁN-PALANQUES Universitat Jaume I Speaking in a Second 55 Language Rosa Alonso Alonso, ed. LAURA ROLDÁN SEVILLANO Universidad de Zaragoza Women on the Move. Body, 60 Memory and Femininity in Present-Day Transnational Diasporic Writing Silvia Pellicer-Ortín and Julia Tofantšuk, eds. -

The Iris Murdoch Review

The Iris Murdoch Review ISSN 1756-7572 Volume I, Number 2, The Iris Murdoch Review Published by the Iris Murdoch Society in association with Kingston University Press Kingston University London, Penrhyn Road, Kingston Upon Thames, KT1 2EE http://fass.kingston.ac.uk/KUP/index.shtml © The contributors, 2010 The views expressed in this Review are the views of the contributors and are not necessarily those of the Iris Murdoch Society Printed in England A record for this journal is available from the British Library 1 The Iris Murdoch Society Appeal on behalf of the Centre for Iris Murdoch Studies by The Iris Murdoch Review is the publication of the Society the Iris Murdoch Society, which was formed at the Modern Language Association Convention in New York City in 1986. It offers a forum for The Iris Murdoch Society actively supports the short articles and reviews and keeps members Centre for Iris Murdoch Studies at Kingston of the society informed of new publications, University in its acquisitioning of new material symposia and other information that has a for the Murdoch archives. It has contributed bearing on the life and work of Iris Murdoch. financially towards the purchase of Iris Murdoch’s heavily annotated library from her study at her Oxford home, the library from her If you would like to join the Iris Murdoch London flat, the Conradi archives, a number of Society and automatically receive The Iris substantial letter runs and other individual Murdoch Review, please contact: items. More detailed information on the collections can be found on the website for the Centre: Penny Tribe http://fass.kingston.ac.uk/research/Iris- Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Murdoch/index.shtml Kingston University London The Centre is regularly offered documents, Penrhyn Road individual letters and letter-runs that are carefully evaluated and considered for funding. -

The Iris Murdoch Review

The Iris Murdoch Review ISSN 1756-7572 Volume 1, Number 3 - The Iris Murdoch Review Published by the Iris Murdoch Society in association with Kingston University Press Kingston University London, Penrhyn Road, Kingston upon Thames, KT1 2EE <http://fass.kingston.ac.uk/kup/> © The contributors, 2011 The views expressed in this Review are the views of the contributors and are not those of the editors. Printed by Lightning Source Cover design and typesetting by Allison Hall We wish to thank Joanna Garber for permission to use the portrait of Iris Murdoch by Harry Weinberger on the cover. A record of this journal is available from the British Library Contents 3 Anne Rowe - Editorial Preface 5 Iris Murdoch – A Postscript to ‘On “God” and “Good”’, with an introduction by Justin Broakes 8 Iris Murdoch – Interview commissioned by Radio New Zeland, first broadcast 1978 16 Jill Paton Walsh - Philosophy and the Novel 29 Peter J. Conradi - Obituary for Philippa Foot 32 Priscilla Martin - Review of A Writer at War: Iris Murdoch Letters and Diaries 1938-46, edited by Peter Conradi 35 Bran Nicol - Review of Literary Lives: Iris Murdoch, by Priscilla Martin and Anne Rowe 37 David J. Gordon - Review of Morality and the Novel, edited by Anne Rowe and Avril Horner 40 Nick Turner - Review of Iris Murdoch and the Moral Imaginations, edited by M.F. Simone Roberts and Alison Scott-Baumann 42 Elaine Morley - Review of Iris Murdoch and her Work: Critical Essays, edited by Mustafa Kırca and Şulle Okuroğlu 44 M.F. Simone Roberts - Review of Iris Murdoch: Philosophical -

Ten Movies About Alzheimer's Disease You Shouldn't Miss

Ten Movies About Alzheimer's Disease You Shouldn't Miss The 2008 Oscar nominations include two Best Actress nods for performances in movies that deal with Alzheimer's disease. Here are ten movies you shouldn't miss that handle the difficult subject of Alzheimer's with grace, dignity, and realism. 1. Away From Her (2007) In Away From Her, Julie Christie is Oscar-nominated for Best Actress for her portrayal of Fiona, a woman with Alzheimer's who voluntarily enters a long-term care facility to avoid being a burden on Grant, her husband of 50 years. After a 30-day separation (recommended by the facility), Grant visits Fiona and finds that her memory of him has deteriorated and that she's developed a close friendship with another man in the facility. Grant must draw upon the pure love and respect he has for Fiona to choose what will ensure his wife's happiness in the face of the disease. Christie has already won a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture (Drama) for her performance in this movie. 2. The Savages (2007) Laura Linney and Philip Seymour Hoffman play siblings in this tragic comedy about adult children caring for a parent with dementia. Laura Linney is Oscar-nominated for Best Actress, and Tamara Jenkins is Oscar-nominated for best original screenplay. A rare combination of humility, dignity, and humor, Philip Seymour Hoffman was Golden Globe-nominated for Best Actor in a Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy) for his performance as the neurotic professor who begrudgingly unites with his sister for the sake of their father. -

Excellent Movies with a Dementia Theme

Away From Her (2007) Image © PriceGrabber In Away From Her, Julie Christie was Oscar-nominated for Best Actress for her portrayal of Fiona, a woman with Alzheimer's who voluntarily enters a long-term care facility to avoid being a burden on Grant, her husband of 50 years. After a 30-day separation (recommended by the facility), Grant visits Fiona and finds that her memory of him has deteriorated and that she's developed a close friendship with another man in the facility. Grant must draw upon the pure love and respect he has for Fiona to choose what will ensure his wife's happiness in the face of the disease. Christie won a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture (Drama) for her performance in this movie. The Savages (2007) Image © PriceGrabber Laura Linney and Philip Seymour Hoffman play siblings in this tragic comedy about adult children caring for a parent with dementia. Laura Linney was Oscar-nominated for Best Actress, and Tamara Jenkins was Oscar-nominated for best original screenplay. A rare combination of humility, dignity, and humor, Philip Seymour Hoffman was Golden Globe- nominated for Best Actor in a Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy) for his performance as the neurotic professor who begrudgingly unites with his sister for the sake of their father. A Song For Martin (2001) Image © PriceGrabber Sven Wollter and Viveka Seldahl -- married in real life -- play married couple Martin and Barbara in this Swedish movie with English subtitles. Martin is a conductor and composer; Barbara, a violinist. They meet and marry in middle-age, but soon after, they find out that Martin has Alzheimer's disease. -

IRIS Oxford in Den 90Er Jahren. Zu Einem Festlichen Abendessen Im

Wettbewerb/IFB 2002 IRIS IRIS IRIS Regie: Richard Eyre Großbritannien/USA 2001 Darsteller Iris Murdoch Judi Dench Länge 90 Min. John Bayley Jim Broadbent Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Junge Iris Kate Winslet Farbe Junger John Hugh Bonneville Janet Stone Penelope Wilton Stabliste Junge Janet Juliet Aubrey Buch Richard Eyre Junger Maurice Samuel West Charles Wood, Maurice Timothy West nach den Büchern College-Leiterin Eleanor Bron „Elegy for Iris“ und Hostess Angela Morant „Iris and Her Friends“ Angestellte Sioban Hayes von John Bayley BBC-Moderatorin Joan Bakewell Kamera Roger Pratt BBC-Assistentin Nancy Carroll Kameraführung Paul Bond Dr.Gudgeon Kris Marshall Schnitt Martin Walsh Neurologe Tom Mannion Schnittassistenz Steve Maguire Postbote Derek Hutchinson Ton Jim Greenhorn Phillida Stone Saira Todd Musik James Horner Emma Stone Juliet Howland Production Design Gemma Jackson Junge Phillida Charlotte Arkwright Ausstattung David Warren Judi Dench Junge Emma Harriet Arkwright Kostüm Ruth Myers Die kleine Stone Matilda Allsopp Maske Lisa Westcott Klavierspieler Steve Edis Regieassistenz Martin Harrison IRIS Polizistin Emma Handy Casting Celestia Fox Oxford in den 90er Jahren. Zu einem festlichen Abendessen im Somerville Taxifahrer Stephen Marcus Herstellungsltg. Michael Dreyer College sind Iris Murdoch, Professorin für Philosophie und berühmte Schrift- Maureen Pauline McGlynn Produktionsltg. Tim Porter stellerin, und ihr Mann, der Literaturprofessor John Bayley, als Ehrengäste Tricia Gabrielle Reidy Aufnahmeleitung Tom Elgood geladen. Iris Murdoch hält eine geistreiche Rede, dann stimmt sie – sehr zur Produzenten Robert Fox Scott Rudin Freude aller Anwesenden – ein irisches Volkslied an: „The Lark in the Clear Executive Producers Anthony Minghella Air“. Sydney Pollack John Bayleys Gedanken schweifen in die Vergangenheit – wie ihm Iris vor Guy East vierzig Jahren bei einem Dinner vorgestellt wurde und er sich, auf der Stelle David M.Thompson von ihr bezaubert, an seinem Wein verschluckte. -

Living on Paper

LIVING ON PAPER LIVING ON PAPER LETTERS FROM IRIS MURDOCH 1934–1995 IRIS MURDOCH Edited by Avril Horner and Anne Rowe Chatto & Windus !#$%#$ ' ( ) * + ', - . / 0 Chatto & Windus, an imprint of Vintage, 0, Vauxhall Bridge Road, London 67'8 06: Chatto & Windus is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com Letters: © Kingston University 0,') Introduction, all footnotes and endmatter © Avril Horner and Anne Rowe, 0,') The moral right of Iris Murdoch to be identi>ed as the author of this work, and Avril Horner and Anne Rowe as its editors, has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act '+--. Ed Victor Ltd are the agents for the Iris Murdoch Estate and handle publication rights to all other works. They can be contacted at [email protected]. United Agents are the agents for >lm, television and dramatic rights. They can be contacted at [email protected]. First published by Chatto and Windus in 0,') www.vintage-books.co.uk A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library JQ X6Q$ +*-,*,''-*,)* Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certi>ed paper. For our grandchildren: Rhiannon, F!on, Owain, Iestyn, Eirian and Huw Rowe and Samuel, Felix, Lulu and Elise Horner Yet words are so damned important now that we’re living on paper again. -

Life in the Glass Case

Eukaryon, vol. 9, March 2013, Lake Forest College Film Review Life in the Glass Case Hannah Samberg* because this was a seemingly impossible task. She took a Department of Biology risk that the project would succeed. The supporting Lake Forest College, character’s dedication to helping Bauby highlights the Lake Forest, Illinois 60045 helplessness he felt, but illustrates for the viewer the positive prognosis of the disease. Seeing people who are helping Jean-Dominique makes us like him, and wish for his Films have played an integral role in society for decades. recovery. The choice Schnabel made to have everyone They impact our lives by exposing multiple sides of around Bauby be optimistic makes the main focus of the controversial topics, reminding us of past experiences, movie the disease and Bauby’s promising but tedious projecting possible futures, and illustrating for us what our treatment and rehabilitation. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly lives could look like if things were different. Movies can accurately depicts Locked-in Syndrome as being mentally educate and indoctrinate their audiences by exploring ethical stressful, but not completely debilitating. In Iris, there is only dilemmas present in society. The two movies Iris and The one other major character besides Iris herself: her husband, Diving Bell and the Butterfly focus on how John. He does not seem fully supportive of Iris as she neurodegenerative diseases affect those involved, develops Alzheimer’s. Early on in her neurodegeneration attempting to impact and educate their viewers with their relationship seems strained, and eventually he has a sentimental narratives of individuals suffering from brain breakdown, yelling and saying he doesn’t want her anymore. -

Catz-The-Year-2015.Pdf

MESSAGES The Year St Catherine’s College . Oxford 2015 ST CATHERINE’S COLLEGE 2015/79 Master and Fellows 2015 MASTER Timothy Cook, MA, DPhil Cressida E Chappell, MA W I F (Bill) David, MA, DPhil Andrew J Bunker, MA, DPhil Peter T Ireland, MA, DPhil Fellow by Special Election (BA, MA Hull) Fellow by Special Election in Tutor in Physics Donald Schultz Professor of Professor Roger W Fellow by Special Election Physics Professor of Astrophysics Turbomachinery Ainsworth, MA, DPhil, FRAeS Richard I Todd, MA status, Academic Registrar DPhil (MA Camb) Secretary to the Governing Richard M Bailey, MA (BSc Adrian L Smith, MA (BSc Pekka Hämäläinen, MA (MA, FELLOWS Tutor in Materials Science Body Leics, MSc, PhD Lond) Keele, MSc Wales, PhD Nott) PhD Helsinki) Goldsmiths’ Fellow Tutor in Geography Tutor in Zoology Rhodes Professor of Fram E Dinshaw, MA, DPhil Professor of Materials David R H Gillespie, MA, Associate Professor in Associate Professor in American History Official Fellow DPhil Geochronology Infectious Diseases Finance Bursar Marc Lackenby, MA (PhD Tutor in Engineering Science Dean (Leave H16-T16) Benjamin A F Bollig, MA (BA Camb) Rolls-Royce Fellow Nott, MA, PhD Lond) Peter D Battle, MA, DPhil Tutor in Pure Mathematics Associate Professor in Gaia Scerif (BSc St And, PhD Andreas Muench, MA (Dr Tutor in Spanish Tutor in Inorganic Chemistry Leathersellers’ Fellow Engineering Science Lond) phil, Dipl TU Munich) (Leave M15-T16) Professor of Chemistry Professor of Mathematics Associate Professor in Tutor in Mathematics Peter P Edwards, MA (BSc, -

Anthony Powell And

The Anthony Powell Society Newsletter Issue 60, Autumn 2015, ISSN 1743-0976, £3 40 years since Dance was completed ... Hearing Secret Harmonies was published on 8 September 1975 Annual General Meeting Saturday 24 October See enclosed papers If you can’t attend, please use your proxy vote London Group AP Birthday Lunch Saturday 5 December Details on page 20 Contents Editorials ............................................... 2 The Purpose of Literature ..................... 3-5 Dance? I’d Rather have Luncheon ...... 6-8 AP & MIL – Further Insights III ........ 9-11 AP and Richard Cobb ....................... 12-16 My First Time ................................... 17-18 Footnote: Charles I Statue ..................... 19 Dates for Your Diary ...................... 20-21 Society News & Notices ................ 22-26 Dance – For a Second Time ............. 27-28 REVIEW: Renishaw Hall................. 29-31 REVIEW: Berenson-Clark Letters ... 32-33 Uncle Giles’ Corner .............................. 34 Letters to the Editor ............................... 35 Cuttings .......................................... 36-38 Merchandise & Membership .......... 39-40 Anthony Powell Society Newsletter #60 A Letter from the Editor From the Secretary’s Desk This edition has an As our august Editor Oxonian flavour. First points out (opposite) this we have a piece about the edition of Newsletter has purpose of literature by a very Oxfordian focus, Robin Bynoe (Hertford) although there is plenty inspired by a quotation else as well. from John Bayley, This is also a well packed Wharton Professor of issue – so well packed in English Literature at fact that it is our largest Oxford, 1974-1992. ever (if you discount Secondly we have Jeff issue 21, the special for Manley's review of My Dear Hugh – AP’s centenary). Never before have we correspondence between Richard Cobb, produced 40 pages – and even that was, at (Professor of Modern History at Oxford, times, a squeeze. -

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

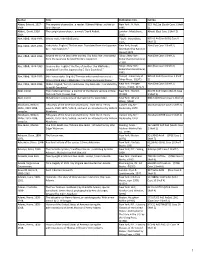

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

IMR 2015.Indd

For Mrs Audhild Bayley Letter from John Bayley to Michael Howard dated January 1955 from the Iris Murdoch Archives at Kingston University Special Collections. See page 60 of this issue for transcription. The Iris Murdoch Review Published by the Iris Murdoch Archive Project in association with Kingston University Press Kingston University London, Penrhyn Road, Kingston Upon Thames, KT1 2EE http://fass.kingston.ac.uk/kup/ © The contributors, 2015 The views expressed in this Review are the views of the contributors and are not those of editors. Printed by Lightning Source Cover design by Sasha Hatherly Typesetting by Aaron Lipschitz We wish to thank Michael Howard for permission to use the photograph of John Bayley for the cover photograph, and the Fryer Library, the University of Queensland Library, for permission to use the photograph of John Bayley on the back cover. A record of this journal is available from the British Library. The Iris Murdoch Society President Barbara Stevens Heusel, Northwest Missouri State University, 800 University Drive Maryville, MO 64468, USA Secretary J. Robert Baker, Fairmont State University, 1201 Locus Ave, Fairmont, WV 26554, USA Administrator Penny Tribe, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Kingston University. Email: [email protected] The Iris Murdoch Review TheIris Murdoch Review (Kingston University Press) publishes articles on the life and work of Iris Murdoch and her milieu. The Review aims to represent the breadth and eclecticism of contemporary critical approaches to Murdoch, and particularly welcomes new perspectives and contexts of inquiry. Lead Editor Anne Rowe, Director of the Iris Murdoch Archive Project, Kingston University, Penrhyn Road, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, KT1 2EE, UK.