ADOBE FRAMEMAKER 8 STRUCTURE APPLICATION DEVELOPER GUIDE © 2007 Adobe Systems Incorporated and Its Licensors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SGML As a Framework for Digital Preservation and Access. INSTITUTION Commission on Preservation and Access, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 417 748 IR 056 976 AUTHOR Coleman, James; Willis, Don TITLE SGML as a Framework for Digital Preservation and Access. INSTITUTION Commission on Preservation and Access, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-1-887334-54-8 PUB DATE 1997-07-00 NOTE 55p. AVAILABLE FROM Commission on Preservation and Access, A Program of the Council on Library and Information Resources, 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 740, Washington, DC 20036-2217 ($20). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Information; Computer Oriented Programs; *Electronic Libraries; *Information Retrieval; Library Automation; Online Catalogs; *Preservation; Standards IDENTIFIERS Digital Technology; *SGML ABSTRACT This report explores the suitability of Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML) as a framework for building, managing, and providing access to digital libraries, with special emphasis on preservation and access issues. SGML is an international standard (ISO 8879) designed to promote text interchange. It is used to define markup languages, which can then encode the logical structure and content of any so-defined document. The connection between SGML and the traditional concerns of preservation and access may not be immediately apparent, but the use of descriptive markup tools such as SGML is crucial to the quality and long-term accessibility of digitized materials. Beginning with a general exploration of digital formats for preservation and access, the report provides a staged technical tutorial on the features and uses of SGML. The tutorial covers SGML and related standards, SGML Document Type Definitions in current use, and related projects now under development. A tiered metadata model is described that could incorporate SGML along with other standards to facilitate discovery and retrieval of digital documents. -

Information Processing — Text and Office Systems — Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML)

International Standard •3 8879 / INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION»ME)KflyHAPOflHAR OPrAHU3AL|Ufl FIO CTAHflAPTH3ALlMM»ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION Information processing — Text and office systems — Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML) Traitement de /'information — Systemes bureautiques — Langage standard generalise de balisage f SGML) First edition — 1986-10-15 Adopted for Use by the Federol Government FIPS PUB 152 See Notice on Inside Front Cover —JK— 468 . A8A3 //152 1988 UDC 681.3.06 Ref. No. ISO 8879-1986 (E) Descriptors : data processing, documentation, logical structure, programming (computers), artificial languages, programming languages Foreword ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International organizations, govern¬ mental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work. Draft International Standards adopted by the technical committees are circulated to the member bodies for approval before their acceptance as International Standards by the ISO Council. They are approved in accordance with ISO procedures requiring at least 75 % approval by the member bodies voting. International Standard ISO 8879 was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 97, In¬ formation processing systems. Users should note that all International Standards undergo revision from time to time and that any reference made herein to any other International Standard implies its latest edition, unless otherwise stated. NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS &' TECHNOLOGY Research Mormatksn Center Gakhersburg, MD £06^9 This standard has been adopted for Federal Government use. -

HTML 4.0 Specification

HTML 4.0 Specification PR-HTML40-971107 HTML 4.0 Specification W3C Proposed Recommendation 7-Nov-1997 This version: http://www.w3.org/TR/PR-html40-971107/ Latest version: http://www.w3.org/TR/PR-html40/ Previous version: http://www.w3.org/TR/WD-html40-970917/ Editors: Dave Raggett <[email protected]> Arnaud Le Hors <[email protected]> Ian Jacobs <[email protected]> Abstract This specification defines the HyperText Markup Language (HTML), version 4.0, the publishing language of the World Wide Web. In addition to the text, multimedia, and hyperlink features of the previous versions of HTML, HTML 4.0 supports more multimedia options, scripting languages, style sheets, better printing facilities, and documents that are more accessible to users with disabilities. HTML 4.0 also takes great strides towards the internationalization of documents, with the goal of making the Web truly World Wide. HTML 4.0 is an SGML application conforming to International Standard ISO 8879 -- Standard Generalized Markup Language [ISO8879] [p.319] ). As an SGML application, the syntax of conforming HTML 4.0 documents is defined by the combination of the SGML declaration [p.247] and the document type definition [p.249] (DTD). This specification defines the intended interpretation of HTML 4.0 elements and adds syntax constraints that may not be expressed by the DTD alone. Status of this document This is a stable document derived from the 17 September working draft of the HTML 4.0 specification. This document has been produced as part of the W3C HTML Activity. The publication of this document does not imply endorsement by the Consortium’s staff or Member organizations. -

An SGML Environment for STEP

An SGML Environment for STEP Usa Phillips Joshua Lubeli U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 NIST NISTIR 5515 An SGML Environment for STEP Lisa Phillips Joshua Lubell U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 June 22, 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Ronald H. Brown, Secretary TECHNOLOGY ADMINISTRATION Mary L. Good, Under Secretary for Techrwlogy NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY Arati Prabhakar, Director Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 The Application Protocol Development Environment 2 3 SGML Basics 4 3.1 Document Type Definition 4 3.2 SGML Document Instance 5 4 Why SGML? 7 4.1 Document Shareability 7 4.2 Structure-based Editing 7 4.3 Automatic Generation of Text 8 4.4 Information Integrity 8 4.5 “Intelligent” Documents 8 4.6 Increased Potential for Collaboration 9 4.7 Reduction In Document Preparation Time 9 5 The SGML Environment for STEP 10 5.1 Essential Components 11 5.1.1 DTD Parser 12 5.1.2 Document Instance Parser 12 5.1.3 STEP-Customized SGML Authoring Tool 12 5.1.4 Conversion of Legacy Documents to SGML 13 5.1.5 Translation from SGML to a Publishable Format 14 5.2 Additional Components 14 5.2.1 Multi-Document Queries and Browsing 15 5.2.2 Remote Access Services 16 5.2.3 Multi-user Editing 17 6 Conclusion 18 6.1 Status of the SGML Environment and Near-term Future Plans 18 6.2 Long-term Plans for the SGML Environment 19 7 References 20 8 Glossary 22 Appendix A: The STEP DTDs 24 DRAFT 1 ' »3S(, . -

Application Developer's Guide (PDF)

MarkLogic Server Application Developer’s Guide 1Application Developer’s Guide MarkLogic 10 May, 2019 Last Revised: 10.0-7, June, 2021 Copyright © 2021 MarkLogic Corporation. All rights reserved. MarkLogic Server Table of Contents Table of Contents Application Developer’s Guide 1.0 Developing Applications in MarkLogic Server ...........................................16 1.1 Overview of MarkLogic Server Application Development .................................16 1.2 Skills Needed to Develop MarkLogic Server Applications ..................................16 1.3 Where to Find Specific Information .....................................................................17 2.0 Loading Schemas .........................................................................................19 2.1 Configuring Your Database ..................................................................................19 2.2 Loading Your Schema ..........................................................................................20 2.3 Referencing Your Schema ....................................................................................21 2.4 Working With Your Schema ................................................................................21 2.5 Validating XML and JSON Data Against a Schema ............................................22 2.5.1 Validating Schemas using Schematron .....................................................22 2.5.2 Validating Schemas using the XQuery validate Expression ....................25 2.5.3 Validating JSON Documents against -

Using SGML As a Basis for Data-Intensive NLP

Using SGML as a Basis for Data-Intensive NLP David McKelvie, Chris Brew & Henry Thompson Language Technology Group, Human Communication Research Centre, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland David. McKelvie@ed. ac. uk ~z Chris. Brew@ed. ac. uk & H. Thompson@ed. ac. uk Abstract cessing of (primarily) text corpora. It generalises the UNIX pipe architecture, making it possible to This paper describes the LT NSL sys- use pipelines of general-purpose tools to process an- tem (McKelvie et al, 1996), an architec- notated corpora. The original UNIX architecture al- ture for writing corpus processing tools. lows the rapid construction of efficient pipelines of This system is then compared with two conceptually simple processes to carry out relatively other systems which address similar is- complex tasks, but is restricted to a simple model of sues, the GATE system (Cunningham et streams as sequences of bytes, lines or fields. LT NSL al, 1995) and the IMS Corpus Workbench lifts this restriction, allowing tools access to streams (Christ, 1994). In particular we address which are sequences of tree-structured text (a repre- the advantages and disadvantages of an sentation of SGML marked-up text). SGML approach compared with a non-SGML The use of SGML as an I/0 stream format between database approach. programs has the advantage that SGML is a well de- fined standard for representing structured text. Its 1 Introduction value is precisely that it closes off the option of a The theme of this paper is the design of software proliferation of ad-hoc notations and the associated and data architectures for natural language process- software needed to read and write them. -

Item 1: SYNTAX

29837 01 pp001-288 r9ah.ps 8/18/03 4:40 PM Page 1 1 ❘ Syntax Syntax is the lowest level of XML. To a large extent the contents of this section focus on the microstructure of XML. By investigating different ways to represent the same structures, the items answer the question, how can XML best be authored for maximum interoperability and conven- ience? Little of what’s discussed here affects the information content of an XML document. However, just as there are better and worse ways to write C code that pro- duces identical machine code when compiled, so too are there better and worse ways to write XML documents. In this section we explore some of the most useful ways to improve the legibility, maintainability, and exten- sibility of your XML documents and applications. Item 1 Include an XML Declaration Although XML declarations are optional, every XML document should have one. An XML declaration helps both human users and automated software identify the document as XML. It identifies the version of XML in use, specifies the character encoding, and can even help optimize the parsing. Most importantly, it’s a crucial clue that what you’re reading is in fact an XML document in environments where file type information is unavailable or unreliable. The following are all legal XML declarations. <?xml version="1.0"?> <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <?xml version="1.0" encoding="ISO-8859-1" standalone="no"?> <?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes"?> In general the XML declaration must be the first thing in the XML docu- ment. -

Adobe Framemaker Structure Application Developer Reference

Adobe FrameMaker Structured Application Developer’s Reference 2 Contents Before You Begin . 5 Chapter 1 Structure Application Definition Reference . 9 Contents of an application definition file . .9 How FrameMaker searches for rules files . 23 Define an application . .9 Specifying a Schema for XML . 23 Providing default information . 11 Specifying an SGML declaration . 24 Specifying the character encoding for SGML files . 11 Managing CSS import/export and XSL transformation 24 Specifying conditional text output . 13 How the Stylesheets element affects CSS Specifying a DOCTYPE element . 13 generation. 24 Specifying a DTD . 14 How the Stylesheets element affects CSS import 25 Specifying entities . 14 How the Stylesheets element affects XSL transformation . 25 Specifying entities through an entity catalog . 15 Specifying the location of individual entities . 16 Specifying a FrameMaker template . 27 Specifying names for external entity files. 17 Specifying a structure API client . 27 Specifying public identifiers . 18 Specifying the character encoding for XML files . 27 Specifying a search path for external entity files 19 Display encoding . 28 Specifying external cross reference behavior . 20 Encoding of CSS files . 29 Change file extension to .XML . 20 Exporting XML . 30 Try alternative extensions . 21 Limiting the length of a log file . 30 Specifying filename extensions . 21 Mapping graphic notations to file types . 31 Enabling namespaces . 22 Defining a Form view for the structured application 31 Specifying a read/write rules document . 22 Specifying MathML options . 32 Specifying a search path for included files in rules documents. 22 Chapter 2 Read/Write Rules Summary . 33 All Elements . 33 Entities . 36 Attributes . 34 Equations . 36 Books . -

Application Developer's Guide (PDF)

MarkLogic Server Application Developer’s Guide 1Application Developer’s Guide MarkLogic 8 February, 2015 Last Revised: 8.0-7, August, 2017 Copyright © 2017 MarkLogic Corporation. All rights reserved. MarkLogic Server Table of Contents Table of Contents Application Developer’s Guide 1.0 Developing Applications in MarkLogic Server ...........................................12 1.1 Overview of MarkLogic Server Application Development .................................12 1.2 Skills Needed to Develop MarkLogic Server Applications ..................................12 1.3 Where to Find Specific Information .....................................................................13 2.0 Loading Schemas .........................................................................................14 2.1 Configuring Your Database ..................................................................................14 2.2 Loading Your Schema ..........................................................................................15 2.3 Referencing Your Schema ....................................................................................16 2.4 Working With Your Schema ................................................................................16 2.5 Validating XML Against a Schema ......................................................................17 3.0 Understanding Transactions in MarkLogic Server ......................................19 3.1 Terms and Definitions ..........................................................................................20 -

Appendix A: Introduction to SGML

Appendix A: Introduction to SGML This appendix gives a very brief introduction to SGML. This should be enough to carry a reader through the first part of this book. If you are not already familiar with SGML, you will benefit from some additional reading. The bibliography lists several books on SGML; van Herwijnen 1994 is a popular and accessible introduction. What is SGML, really? SGML is short for Standard Generalized Markup Language, and it is defined by ISO Standard 8879 (1986). It provides a flexible and portable way of representing documents on computers, where you can choose what kinds of components occur in each particular type of document, and then clearly label those parts as they occur. The foundation of SGML, and to my thinking the primary reason it has gained such wide acceptance, is very simple: It lets you describe document structures directly, rather than describing something temporary like formatting, that depends on the structure. Simply put, SGML lets you tell the truth about your documents. This is reflected in five key characteristics that form the basis of its wide acceptance: • Descriptive markup: An SGML document consists of objects of various classes (chapters, titles, references, repair procedures, graphic objects, poems, etc.), not sequences of formatting instructions. These objects are called elements, and each one has a generic element type. SGML marks Ehe boundaries of elements using start- and end- tags . For example, a quotation could be stored as: I<QUOTATION>Full speed ahead</QUOTATION> I 19 6 DeRose By labeling elements themselves rather than saying what to do with them, SGML avoids locking information into one program or e,)en one purpose. -

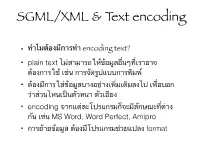

SGML/XML & Text Encoding

SGML/XML & Text encoding • ทไมตองมการท encoding text? • plain text ไมสามารถใหขอมลอนๆทเราอาจ ตองการใช เชน การจดรปแบบการพมพ • ตองมการใสขอมลบางอยางเพมเตมลงไป เพอบอก วาสวนไหนเปนตวหนา ตวเอยง • encoding จากแตละโปรแกรมกจะมลกษณะทตาง กน เชน MS Word, Word Perfect, Amipro • การยายขอมล ตองมโปรแกรมชวยแปลง format SGML/XML & Text encoding • ในทาง linguistics เรากจเปนทตอง markup ขอมลทางภาษาศาสตรบางอยางเขาไปใน corpus เพอใชในการวเคราะหทางภาษาศาสตร • เชน ถาตองการศกษาในระดบ syntax corpus ก จะตองม basic syntactic information เชน part of speech อยดวย linguistic annotation แบบตางๆ • Part-of-Speech tagging • This example is taken from the Spoken English Corpus and used the C7 tagset: Perdita&NN1-NP0; ,&PUN; covering&VVG; the&AT0; bottom&NN1; of&PRF; the&AT0; lorries&NN2; with&PRP; straw&NN1; to&TO0; protect&VVI; the&AT0; ponies&NN2; '&POS; feet&NN2; ,&PUN; suddenly&AV0; heard&VVD-VVN; Alejandro&NN1-NP0; shouting&VVG; that&CJT; she&PNP; better&AV0; dig&VVB; out&AVP; a&AT0; pair&NN0; of&PRF; clean&AJ0; breeches&NN2; and&CJC; polish&VVB; her&DPS; • ตวอยาง codes ทใช – AJ0: general adjective POS: genitive marker – AT0: article, neutral for number PNP: pronoun – AV0: general adverb PRF: of – AVP: prepositional adverb PRP: prepostition – CJC: co-ordinating conjunction PUN: punctuation – CJS: subordinating conjunction TO0: infintive to – CJT: that conjunction VBI: be – DPS: possessive determiner VM0: modal auxiliary – DT0: singular determiner VVB: base form of lexical verb – NN0: common noun, neutral for VVD: past tense form of lexical verb number VVG: -ing form of lexical verb – NN1: singular common noun VVI: infinitive form of lexical verb – NN2: plural common noun VVN: past participle form of lexical verb – NP0: proper noun • Syntactic annotation คอการ mark ขอมลทางดาน syntax เขาไปใน text เชน corpus ของ text ทถก parse แลวจนได tree structure ของแตละประโยค หรอเรยกอกอยางวา treebank ตย. -

TEI Lite: an Introduction to Text Encoding for Interchange Lou Burnard C

TEI Lite: An Introduction to Text Encoding for Interchange Lou Burnard C. M. Sperberg-McQueen June 1995, revised May 2002 Prefatory note TEI Lite was the name adopted for what the TEI editors originally conceived of as a simple demonstration of how the TEI encoding scheme might be adopted to meet 90% of the needs of 90% of the TEI user community. In retrospect, it was predictable that many people should imagine TEI Lite to be all there is to TEI, or find TEI Lite to be far too heavy for their needs (to meet the latter criticism, Michael also prepared a special barebones version of TEI Lite). TEI Lite was based largely on our observations of existing and previous practice in the encoding of texts, particularly as manifest in the collections of the Oxford Text Archive and in our own experience. It is therefore unsurprising that it seems to have become, if not a de facto standard, at least a common point of departure for electronic text centres and encoding projects world wide. Maybe the fact that we actually produced this shortish, readable, manual for it also helped. That manual was, of course, authored and is maintained in the DTD it describes, originally as an XML document. This makes it easy to produce a number of differently formatted versions in HTML, PDF, etc., some of which can be found in The TEI Vault. Early adopters of TEI Lite included a number of ‘Electronic Text Centers’, many of whom produced their own documentation and tutorial materials (some examples are listed in the TEI Tutorials pages).