Undressing the Androgynous Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At Home with Hicks

AT HOME WITH HICKS A rare female star in the world of architecture, Sophie Hicks has designed store concepts for Chloé, Paul Smith and Yohji Yamamoto. Famous for her androgynous style, unflappable manner and tremendous energy, she works from an office on the top floor of her home in Notting Hill, London. Sophie describes her process about getting inside the heads of her clients, most recently Jonny Johansson of Acne Studios, whose new store in Seoul she designed. Photography Brett Lloyd Conversation Skye Sherwin 50 51 Projects like Acne Studios new flagship bou- He can take me out of my comfort zone. I’m very rough concrete floors, concrete columns and tique in Seoul and designing Chloé’s interna- happy to take risks.” a floating concrete staircase, all encased in an tional store concept, have earned Sophie Hicks opaque ‘lightbox’. Did you have a very specific the title ‘fashion’s architect’. Yet the London- Did you know him before that commission? brief from Jonny Johansson? based 55-year-old’s CV is far more varied than You’re both very invested in architecture, but as “No. What I do with all new fashion clients that moniker might imply. From her early days as you say his work is so different from your own. is an in-depth study of who they are, and what’s a teenage stylist at Harpers & Queen and, a few “I’d worked with him for a store in Tokyo the character of what they create. I didn’t know years later, as fashion editor at British Vogue, called Red Ear Jeans when I was working with Sweden at all, so I also tried to find out a bit she’s been known for her vision and drive, not Paul Smith. -

Feminist Statements in Fashion Marketing – and Their Affect on Brand Image

FEMINIST STATEMENTS IN FASHION MARKETING – AND THEIR AFFECT ON BRAND IMAGE Examensarbete – Kandidat Företagsekonomi Julia Ward Maximilian Wollbeck 2016.1.04 Svensk titel: Feministiska Ställningstaganden i Modemarknadsföring -och deras påverkan på brand image Engelsk titel: Feminist Statements in Fashion Marketing –and Their Affect on Brand Image Utgivningsår: 2016 Författare: Julia Ward & Maximilian Wollbeck Handledare: Martin Behre Abstract Sweden is moving towards a society where not being a feminist is considered unmodern and conservative. People are fighting for women's rights and equality between the sexes. This feminist movement in Sweden is starting to show in more and more businesses. The fashion business has recently adapted the same movement and feminism has been used in different types of marketing, such as gender neutral merchandising or statement advertisements. The focus of this thesis is statements on products and the purpose is to investigate how Swedish consumers’ brand image of a high end fashion brand is affected by the brand using symbols of feminist statements on their products. The theoretical framework has been separated into three categories; Brand Image, Consumer Behaviour and Politics in Fashion, which sums up in a conceptual model. The model is tested in the empirical findings that were discovered through two focus groups. Consumers critical minds and high awareness of companies advertising techniques results in the conclusion that consumers demand more political effort in order to trust and accept the statement, apparently an important factor when it comes to change of brand image. Keywords: Brand Image, Consumer Behaviour, Feminism, Politics, Brand Loyalty, Symbolic Interpretation, Brand Negotiation I Sammanfattning Sverige närmar sig ett samhälle där att inte kalla sig för feminist anses omodernt och konservativt. -

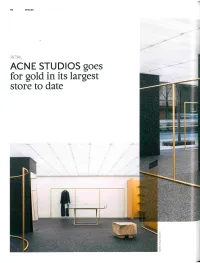

For Gold in Its Largest Store to Date

98 SPACES RETAIL ACNE STUDIOS goes for gold in its largest store to date By juxtaposing asphalt with gold detailing, Acne Studios elevates the status of the crude substance in its New York City flagship. 100 SPACES NEW YORK CITY - At first glance, the only thing that seems to be different about Acne Studios' New York City flagship is the pre• dominant colour. Whereas recent boutiques embraced the austerity of steel, creative director Jonny Johansson went for gold in the largest store to date, which signals another step in the brand's US expansion. A simple switcheroo of questionable note- worthiness, perhaps, but the fashion house has an undeniable way with materials that feels ahead of the retail curve, regardless of how quickly its aesthetic evolves. Another take reveals more at play than just the Midas touch — the result of electrostatically gilded aluminium walls and fittings - as gold features are offset by asphalt, a by-product of the oil industry that was spotted in sculptural objects by Quintus Kropholler during Milan Design Week 2014 (Frame 99, p. 141). Here, how• ever, it's been transformed into an interior surface that covers the floor and structural columns. While its juxtaposition with gold lifts the crude substance to a level befitting the brand, the asphalt is punctuated by a smattering of semiprecious stones to write the highbrow message home. It's really the mix of materials that sets Acne stores apart, a hunch that Johansson corroborates: What interests me most is how you combine materials more than the materials themselves. I always look at the space first and where it's located before considering which ones to use.'The inclusion of gold, for instance, will be exclu• sive to the Madison Avenue flagship, which Johansson says 'elevates it into something spectacular that fits the location'. -

Acne Studios

Acne Studios Autumn/Winter 2016 Erin Bookman Acne Studios Target Customer • Ages 25-35 • Fashion risk takers • Values quality clothing • Both men and Women • Independent personalities • High income level, Acne products are seen as an investment • Live in larger, urban cities around the world • Interested or work in the creative industry • The Acne customer reads intelligent publications that leave room For creative interpretation and uniqueness. Top Competitors • Prabal Gurung • The Row • Proenza Schouler • Alexander Wang • Comme de Garcons Acne Overview Acne Studios is a Stockholm based fashion house founded in 1996, known worldwide for its unprecedented products. Founder and creative director Jonny Johansson’s immense interest in the evolvinG culture of art and fashion around him has influenced its identity in creatinG what is one of the world’s most well respected ready to wear brands today. Johansson’s attention to detail and desiGn, especially throuGh use of tailorinG and fabric have played a crucial role in the brand’s character. Acne’s custom developed products cover an eclectic ranGe of merchandise includinG men’s and women’s ready to wear, footwear, accessories, and denim. In addition to Acne’s headquarters in Stockholm, flaGship stores are also located in Paris, London, New York City, Los AnGeles, and Tokyo. What’s Selling Now Inspiration Fabrication Solid Cotton/Nylon shirt 63% Cotton 37% Nylon Retail Price $290.00 Fabrication Denim (heavy) 100% Cotton Retail Price $440.00 Fabrication Valde Double MalanGe Jacket 85% Wool 15% Cashmere Retail Price $1500.00 Style 1040 Short Sleeve Rider Shirt Silhouette Cropped short sleeve shirt Pointed collar Arm stitch detailinG Fabrication MoraG Poplin Plaid 100% Cotton Retail Price $150.00 Style 1050 Cropped Pant with stripes Silhouette Cropped StraiGht leg pant with cut-out detail LarGe pocket detail Fabrication Murol raw Wool 75% Vi/Fl. -

Beijing Retail Guide

BEIJING Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | 2019 0 China’s national capital outperformed all other Chinese cities again in terms of total retail sales of RMB 1174.77 billion in 2018. The current stock of shopping centres is 6.6 million sqm of GFA. As well as having a resident population of 21.70 million, the Beijing retail market also benefits from being a centre of government and tourism. Gifting, which is deep-rooted in Chinese culture, has historically been a major factor boosting the sales of luxury brands, however in recent years this has been restricted by government. Over 200 million tourist nights in Beijing also provide a boost to retail sales. BEIJING OVERVIEW Cushman & Wakefield | 2019 1 BEIJING KEY RETAIL STREETS & AREAS XIDAN WANGFUJING Xidan is a well known traditional city-level retail submarket Wangfujing is located in the Dongcheng District and is one which is particularly popular amongst the youth. Xidan of the Chinese capital's most famous shopping areas. The currently has a mix of shopping centres and department majority of the main shopping area is pedestrianised and stores totalling around 626,945 sqm, but is best known for is a very popular shopping destination for both tourists Joy City, which houses an exciting range of mid market and residents of the capital. Here, established malls and brands including Apple, UNIQLO and Zara. Xidan’s retail street shops offer a range of brands ranging from Louis area has moved up-scale with new brands like Sandro, Vuittion, Chanel, Burberry and Zegna to LEGO, Apple, Maje, Victoria‘s Secret , etc, which has brought some Pandora, ba&sh and NEIWAI. -

Acne Studios *

ACNE STUDIOS * BRAND IDENTITY ANALYSIS BA HONS FASHION PR London College of Fashion Ilona Angelova Year 1 Katerina Jebb Self Portrait - 2003 Hans Bellmer The doll William Wegman Andre Kertesz In the dark a coat rack looks like a man- 1972 Benjamin Alexander Huseby Goodbye Johnny - Primal Scream Andrea Larsson Ten magazine - September 2011 Jack Pierson Andre Simeons Gallery (left) Angel Youth (right) Jamie Hawkesworth Benjamin Alexander Huseby Stills from Goodbye Johnny Angel music video for Primal Scream Mattias Karlsson Mattias Karlsson For Acne Paper THE LETTER The pages of this book are a written and visual analysis, which have the aim to illustrate understanding of the world of the fashion brand Acne Studios. It looks at the different creative individuals with whmo the brand has collaborated with through the years. The book looks at selected campaigns, collaborations and collections and represents the works by single images on pages, in order to visually engage and capture the values of Acne Studios’ creative team. The analyses are based on the concept - look at the brand’s surrounding in order to understand the creative director and the brand from inside. The book is created as a magazine, where flipping through the pages instead finding adverts as a beginning, it provides visuals of the work of artists, photographers and stylists involved in Acne’s work. This idea is based on the idea of ‘tell me who your friends are and I will tell you who you are.’ It believes that showing people’s work gives a visual experience of their personalities, visual aesthetics and values. -

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 the New Age of Fashion and Luxury Contents

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 The new age of fashion and luxury Contents Foreword 3 Quick statistics 4 The new age of fashion and luxury 5 Top 10 highlights 17 Top 100 24 Geographic analysis 31 Product sector analysis 37 New entrants 42 Fastest 20 43 Study methodology and data sources 45 Endnotes 47 Contacts 50 Foreword Welcome to the seventh edition of Global Powers of Luxury Goods. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted many losses: human, social and economic. What we are now experiencing is an unprecedented moment of crisis in modern history. However, it is during uncertain times that companies often come up with new ideas, converting the crisis into an opportunity, and adopting a long-term vision of future challenges. This prolonged disruptive situation is creating profound changes in consumer behavior and how companies are responding to these changes—prompting a debate about the future of the fashion and luxury industry. There is a general feeling of rethinking luxury and driving it in new directions, considering which business models will be feasible and more relevant in the new normal. Tradition and responsiveness, two elements that have always characterized luxury companies, will both be required to face great challenges in the post-COVID environment. We see the pandemic acting as a divider between the old way of doing business and the new scenario that is taking shape, characterized by changing consumer behavior. Hence, in this report, we talk about a new age for fashion and luxury and will explore the main trends that will drive the industry in the coming months. -

The Swedish Invasion of Los Angeles Is a Real Thing, but It's As Subtle And

THE NEED FOR SWEDES The Swedish invasion of Los Angeles is a real thing, but it’s as subtle and sophisticated as you’d imagine By Lydia Siriprakorn l Caffé, Acne Studios, Swedish crowds gath- ered in a modern, minimalist hotel lobby. Yes, Downtown Los Angeles is looking a lot like Stockholm lately. Angelenos can now dress, groom, caffeinate and even party like the Swedes, no Allen Wrench required. Sleek, sim- ple and refined are the true markings of Swedish design, fashion and, naturally, the takeover of ACNE L.A.’s Fashion District. In less than a year, the formerly gritty pocket of DTLA has transformed into the city’s new upscale Swedish hotspot. Even before a slew of Scandinavian retailers turned the neighborhood into a cultural hub, the takeover had been long in the works. Swedes first infiltrated American culture where we may have needed them most—over the airwaves and in our closets. How did we ever party without Avicii, Icona Pop, Robyn or Röyksopp? Swedes dominate the electronic dance music scene. And who can even remember what well-coiffed, AUSTERE IL CAFFÉ MODEL: COURTESY ACNE STUDIOS 32 FRONTIERSMEDIA.COM good-looking men wore before H&M joined us stateside almost 15 years ago? Americans know While sleek and sexy seemed unlikely and laughable in DTLA’s Fashion District just a few years ago, it appears to be maybe three big, JOIN THE the new reality of the block bordering the ever-trendy Ace Hotel. It’s not just the area’s new high-end favorites—like Stockholm general broad strokes clothing brand Acne Studios or the Scandinavian retail wonder- REVOLUTION land Austere—adding to our insatiable appetite for all things about Sweden, Here’s how to build your own minimalist, Swedish; it’s their signature minimalist look that has turned Sweden-approved look this former Broadway wasteland into an upscale destination. -

AMV Lecture 9 January 2019 Fashion Cultures INTRO

FASHION IN CULTURE UWAS-C0028 Professor Annamari Vänskä Department of Design Aalto University [email protected] FASHION IN CULTURE (3–5 cr.) • Teaching time: 9.1.–20.3.2019 • Lectures, visit to Kiasma • Some important aspects of fashion and culture with visiting scholars and experts • Fashion as representation of culture and its values PASSING THE COURSE • 3 credits: Attend lectures and read texts pertaining to lectures • 5 credits: Attend lectures, read texts and write a learning diary • Deadline for returning the learning diary: March 31 2019. Late admissions are not accepted! • Program, texts and instructions for writing the learning diary are on the MyCourses website: https://mycourses.aalto.fi/course/view.php?id=22557 GRADING • You are expected to attend at least 80 % of the total number of lectures • Assesment: pass/fail Some statistics • Enrolled students: 65 • Students from Aalto ARTS: 42 • Students from Aalto BIZ: 12 • Students from Aalto SCI & ENG: 8 • Exchange students: 2 • JOO-students: 1 INTRO TO THE COURSE CLOTHING? TRENDS? BUSINESS? CHANGE? CULTURE? Karl Lagerfeld / Chanel with models staging a demonstration at the end of his Spring/Summer 2015 collection, Paris Fashion Week, SeptemBer 30, 2014 Givenchy, New York Fashion Week SeptemBer 11, 2015, Spring/Summer 16 collection Chanel and Givenchy – Celebrity audience Fashion: A system • Fashion is more than just clothes • Fashion is an economic system • Fashion is a cultural and symbolic system • Fashion belongs to the realm of sociality and culture • As an economic system and as an industry fashion covers fashionable clothes, accessories, beauty • As a cultural system fashion covers issues such as class, gender, sexuality, religion, morality, ethnicity, consumer behaviour and business – themes that will be addressed on this course • Fashion studies is a multidiscpiplinary field 16.1. -

1. Acne Studios Sustainability Report 2017–18 Acne Studios Sustainability Report 2017–18

1. Acne Studios Sustainability Report 2017–18 Acne Studios Sustainability Report 2017–18 2. Acne Studios Sustainability Report 2017–18 Recap of the year This Sustainability Report covers the financial year (FY) 17/18, which runs from 1 September 2017 to 31 August 2018. In short, the year can be summarised as follows: – More than 800 employees of which over 200 is based at our HQ in Stockholm – 7 offices in Scandinavia, Italy, Paris, New York and Shanghai – Roughly 2.1 billion SEK turnover – 56 Acne Studios stores in 14 countries on 4 continents – Flag ship stores in Stockholm, Paris, London, New York City, Los Angeles and Tokyo – E-commerce in 64 markets – Wholesale distribution via around 800 stores and online shops in 49 countries – 76 suppliers with more than 150 production locations in 15 countries 3. Acne Studios Sustainability Report 2017–18 Our sustainability ambition Acne Studios was founded in 1996 in Stockholm, Sweden, as part of the creative collective ACNE that focused on graphic design, film, production and advertising. 10 years later in 2006, Acne Studios became a standalone fashion company and separated from the collective ACNE. We continue to honour our multidisciplinary heritage and merge the worlds of art and fashion, by incorporating various elements of architecture, photography and Swedish culture into our designs. Our collection includes men’s and women’s ready-to-wear, footwear, accessories and denim. Over the years, Acne Studios has grown into a global fashion company that annually produces over 1.5 million products in 14 countries that are sold worldwide. Our social and environmental impact, and the responsibilities that come with this, have grown along with us. -

BRANDING by DOING - a Study in Refraining from Traditional Marketing

Bachelor Programme in Business Studies Bachelor Thesis BRANDING BY DOING - a study in refraining from traditional marketing Authors: Tutor: Michael Arvidsson Ellinor Torsein Robin Agné Business and administration; Marketing Spring 2011 Abstract Title: “Branding by doing” – a study in refraining from traditional marketing Course: Bachelor thesis in Marketing, 15 ECTS, School of Business, Economics and Law, University of Gothenburg Authors: Michael Arvidsson & Robin Agné Tutor: Ellinor Torsein Keywords: Acne Studios, brands, “Branding by doing”, communication channels, fashion industry, non-traditional marketing communications, The Swedish fashion wonder, traditional marketing communications, word-of-mouth marketing Purpose: To determine required conditions to adopt “Branding by doing” as a marketing approach in the Swedish fashion industry. Research questions: Question 1: What conditions are required of a company to refrain from traditional marketing communications? Question 2: How is “Branding by doing” applied in practice? Question 3: For what reasons do companies refrain from traditional marketing communications? Methodology: This thesis has a hermeneutical approach. A qualitative research method is used and empirical results are based on a case study. Theoretical framework: Theories of brand management and word-of-mouth marketing. Empirical results: The primary data is collected from interviews with Suhrab Lachin, Credit & HR Manager at Acne Studios and Daniel Björk, fashion journalist and author. Conclusions: There are four main conditions required in order to apply “Branding by doing”; product focus and uniqueness, an elaborate corporate culture, a strong customer relationship, consequence and clearness in actions. The product becomes the main communication channel of the brand. 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank our tutor Ellinor Torsein for her support and guidance during the process of this study. -

Retail360 / Connected Stores

Transforming store fl eet through technology Retail360 / Connected Stores Transforming store fl eet through technology January 2018 1 Connected Stores Preface You’re about to read the paper ‘Connected Stores: transforming store fl eet through technology’. Inside are the results of a thrilling experiment - a tale we’ll try to do justice to throughout this paper, which is aimed at providing guidance to retailers around the world. We wrote this paper for executives that are interested in retail innovation & technology, specifi cally those who work with brick & mortar stores. It’s been fi ve years since we predicted that digital channels would reshape store footprints. This year, we saw retailers investing to make that happen. This was also the year we reinvented stores as we knew them, opened shops based on data, and used smart technology to generate insights. We did away with ‘black boxes’ where customers went into shops and revenue fl owed out, and said yes to new and exciting store concepts that deliver outstanding experiences. To refl ect on this retail renaissance, we joined forces with PTC (IoT platforms), Monolith (Computer Vision), Impinj (RFID) and NCR Corporation (POS) to create an alliance with enough capabilities to connect stores and learn from the process. We were honoured when Legend World Wide, a Serbian fashion retailer let us use their fl agship store in the high streets of Belgrade, Serbia, as an innovation lab. The experience with Legend World Wide proved invaluable, and everyone benefi ted. The store is now up and running, and we are continuing to learn from it.