Wing Tip.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

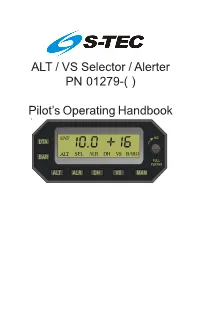

ALT / VS Selector/Alerter

ALT / VS Selector / Alerter PN 01279-( ) Pilot’s Operating Handbook ENT ALT SEL ALR DH VS BARO S–TEC * Asterisk indicates pages changed, added, or deleted by List of Effective Pages current revision. Retain this record in front of handbook. Upon receipt of a Record of Revisions revision, insert changes and complete table below. Revision Number Revision Date Insertion Date/Initials 1st Ed. Oct 26, 00 2nd Ed. Jan 15, 08 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 i S–TEC Page Intentionally Blank ii 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 S–TEC Table of Contents Sec. Pg. 1 Overview...........................................................................................................1–1 1.1 Document Organization....................................................................1–3 1.2 Purpose..............................................................................................1–3 1.3 General Control Theory....................................................................1–3 1.4 Block Diagram....................................................................................1–4 2 Pre-Flight Procedures...................................................................................2–1 2.1 Pre-Flight Test....................................................................................2–3 3 In-Flight Procedures......................................................................................3–1 3.1 Selector / Alerter Operation..............................................................3–3 3.1.1 Data Entry.............................................................................3–3 -

How Doc Draper Became the Father of Inertial Guidance

(Preprint) AAS 18-121 HOW DOC DRAPER BECAME THE FATHER OF INERTIAL GUIDANCE Philip D. Hattis* With Missouri roots, a Stanford Psychology degree, and a variety of MIT de- grees, Charles Stark “Doc” Draper formulated the basis for reliable and accurate gyro-based sensing technology that enabled the first and many subsequent iner- tial navigation systems. Working with colleagues and students, he created an Instrumentation Laboratory that developed bombsights that changed the balance of World War II in the Pacific. His engineering teams then went on to develop ever smaller and more accurate inertial navigation for aircraft, submarines, stra- tegic missiles, and spaceflight. The resulting inertial navigation systems enable national security, took humans to the Moon, and continue to find new applica- tions. This paper discusses the history of Draper’s path to becoming known as the “Father of Inertial Guidance.” FROM DRAPER’S MISSOURI ROOTS TO MIT ENGINEERING Charles Stark Draper was born in 1901 in Windsor Missouri. His father was a dentist and his mother (nee Stark) was a school teacher. The Stark family developed the Stark apple that was popular in the Midwest and raised the family to prominence1 including a cousin, Lloyd Stark, who became governor of Missouri in 1937. Draper was known to his family and friends as Stark (Figure 1), and later in life was known by colleagues as Doc. During his teenage years, Draper enjoyed tinkering with automobiles. He also worked as an electric linesman (Figure 2), and at age 15 began a liberal arts education at the University of Mis- souri in Rolla. -

CESSNA WING TIPS - EMPENNAGE TIPS CESSNA WING TIPS These Wing Tip Kits Consist of a Left and Right Hand Drooped Fiberglass Wing Tip

CESSNA WING TIPS - EMPENNAGE TIPS CESSNA WING TIPS These wing tip kits consist of a left and right hand drooped fiberglass wing tip. These wing tips are better than those manufactured by Cessna because they are made of fiberglass rather than a royalite type material, that bends and CM cracks after a short time on the aircraft. The superior epoxy rather than polyester fiberglass is used. Epoxy fiberglass has major advantages over a royalite type material; It is approximately six timesstronger and twelve times stiffer, it resists ultraviolet light and weathers better, and it keeps its chemical composition intact much longer. With all these advantages, they will probably be the last wingtips that will ever have to be installed on the aircraft. Should these wing tips be damaged through some unforeseen circumstances, they are easily repairable due to their fiberglass construc- tion. These kits are FAA STC’d and manufactured under a FAA PMA authority. The STC allows you to install these WP modern drooped wing tips, even if your aircraft was not originally manufactured with this newer, more aerodynamically efficient wingtip. *Does not include the Plate lens. Plate lens must be purchased separately. **Kits includes the left hand wing tip, right hand wing tip, hardware, and the plate lens Cessna Models Kit No.** Price Per Kit All 150, A150, 152, A152, 170A & B, P172, 175, 205 &L19, 172, 180, 185 for model year up through 1972.182, 206 for 05-01526 . model year up through 1971, 207 from 1970 and up (219-100) ME 05-01545 172, R172K(172XP), 172RG, 180, 185 for model year 1973 and up, 182, 206 for model year 1972 and up. -

Installation Manual, Document Number 200-800-0002 Or Later Approved Revision, Is Followed

9800 Martel Road Lenoir City, TN 37772 PPAAVV8800 High-fidelity Audio-Video In-Flight Entertainment System With DVD/MP3/CD Player and Radio Receiver STC-PMA Document P/N 200-800-0101 Revision 6 September 2005 Installation and Operation Manual Warranty is not valid unless this product is installed by an Authorized PS Engineering dealer or if a PS Engineering harness is purchased. PS Engineering, Inc. 2005 © Copyright Notice Any reproduction or retransmittal of this publication, or any portion thereof, without the expressed written permission of PS Engi- neering, Inc. is strictly prohibited. For further information contact the Publications Manager at PS Engineering, Inc., 9800 Martel Road, Lenoir City, TN 37772. Phone (865) 988-9800. Table of Contents SECTION I GENERAL INFORMATION........................................................................ 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 SCOPE ............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 EQUIPMENT DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................... 1-1 1.4 APPROVAL BASIS (PENDING) ..................................................................................... 1-1 1.5 SPECIFICATIONS......................................................................................................... 1-2 1.6 EQUIPMENT SUPPLIED ............................................................................................ -

Aircraft Winglet Design

DEGREE PROJECT IN VEHICLE ENGINEERING, SECOND CYCLE, 15 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2020 Aircraft Winglet Design Increasing the aerodynamic efficiency of a wing HANLIN GONGZHANG ERIC AXTELIUS KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES 1 Abstract Aerodynamic drag can be decreased with respect to a wing’s geometry, and wingtip devices, so called winglets, play a vital role in wing design. The focus has been laid on studying the lift and drag forces generated by merging various winglet designs with a constrained aircraft wing. By using computational fluid dynamic (CFD) simulations alongside wind tunnel testing of scaled down 3D-printed models, one can evaluate such forces and determine each respective winglet’s contribution to the total lift and drag forces of the wing. At last, the efficiency of the wing was furtherly determined by evaluating its lift-to-drag ratios with the obtained lift and drag forces. The result from this study showed that the overall efficiency of the wing varied depending on the winglet design, with some designs noticeable more efficient than others according to the CFD-simulations. The shark fin-alike winglet was overall the most efficient design, followed shortly by the famous blended design found in many mid-sized airliners. The worst performing designs were surprisingly the fenced and spiroid designs, which had efficiencies on par with the wing without winglet. 2 Content Abstract 2 Introduction 4 Background 4 1.2 Purpose and structure of the thesis 4 1.3 Literature review 4 Method 9 2.1 Modelling -

Using an Autothrottle to Compare Techniques for Saving Fuel on A

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2010 Using an autothrottle ot compare techniques for saving fuel on a regional jet aircraft Rebecca Marie Johnson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Rebecca Marie, "Using an autothrottle ot compare techniques for saving fuel on a regional jet aircraft" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11358. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11358 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Using an autothrottle to compare techniques for saving fuel on A regional jet aircraft by Rebecca Marie Johnson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Electrical Engineering Program of Study Committee: Umesh Vaidya, Major Professor Qingze Zou Baskar Ganapathayasubramanian Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2010 Copyright c Rebecca Marie Johnson, 2010. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION I gratefully acknowledge everyone who contributed to the successful completion of this research. Bill Piche, my supervisor at Rockwell Collins, was supportive from day one, as were many of my colleagues. I also appreciate the efforts of my thesis committee, Drs. Umesh Vaidya, Qingze Zou, and Baskar Ganapathayasubramanian. I would also like to thank Dr. -

P:\Dokumentation\Manual-O\DA 62\7.01.25-E

DA 62 AFM Ice Protection System Supplement S03 FIKI SUPPLEMENT S03 TO THE AIRPLANE FLIGHT MANUAL DA 62 ICE PROTECTION SYSTEM FOR FLIGHT INTO KNOWN ICING Doc. No. : 7.01.25-E Date of Issue of the Supplement : 01-Apr-2016 Design Change Advisory : OÄM 62-003 This Supplement to the Airplane Flight Manual is EASA approved under Approval Number EASA 10058874. This AFM - Supplement is approved in accordance with 14 CFR Section 21.29 for U.S. registered aircraft and is approved by the Federal Aviation Administration. DIAMOND AIRCRAFT INDUSTRIES GMBH N.A. OTTO-STR. 5 A-2700 WIENER NEUSTADT AUSTRIA Page 9-S03-1 Ice Protection System DA 62 AFM FIKI Supplement S03 Intentionally left blank. › Page 9-S03-2 05-May-2017 Rev. 2 Doc. # 7.01.25-E DA 62 AFM Ice Protection System Supplement S03 FIKI 0.1 RECORD OF REVISIONS Rev. Chap- Date of Approval Date of Date Signature Reason Page(s) No. ter Revision Note Approval Inserted Rev. 1 to AFM Supplement S03 to AFM 9-S03-1, Doc. No. FAA 7.01.25-E is 1 0 9-S03-3, 10 Oct 2016 14 Oct 2016 Approval approved by 9-S03-4 EASA with Approval No. EASA 10058874 › Rev. 2 to AFM › Supplement › S03 to AFM › Doc. No. › TR-MÄM › All, except 7.01.25-E is › 2 62-254, 05 May 2017 › All approved 13 Nov 2017 › Corrections Cover Page › under the › authority of › DOA › No.21J.052 › Doc. # 7.01.25-E Rev. 2 05-May-2017 Page 9-S03-3 Ice Protection System DA 62 AFM FIKI Supplement S03 0.3 LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES Chapter Page Date 9-S03-1 10-Oct-2016 › 9-S03-2 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-3 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-4 05-May-2017 0 › 9-S03-5 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-6 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-7 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-8 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-9 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-10 05-May-2017 1 › 9-S03-11 05-May-2017 › 9-S03-12 05-May-2017 › appr. -

Ac 120-67 3/18/97

Advisory u.s. Department ofTransportation Federal Aviation Circular Ad.nnlstratlon Subject: CRITERIA FOR OPERATIONAL Date: 3/18/97 AC No: 120-67 APPROVAL OF AUTO FLIGHT Initiated By: AFS-400 Change: GUIDANCE SYSTEMS 1. PURPOSE. This advisory circular (AC) states an acceptable means, but not the only means, for obtaining operational approval of the initial engagement or use of an Auto Flight Guidance System (AFGS) under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 121, section 121.579(d); part 125, section 125.329(e); and part 135, section 135.93(e) for the takeoff and initial climb phase of flight. 2. APPLICABILITY. The criteria contained in this AC are applicable to operators using commercial turbojet and turboprop aircraft holding Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) operating authority issued under SPAR 38-2 and 14 CFR parts 119, 121, 125, and 135. The FAA may approve the AFGS operation for the operators under these parts, where necessary, by amending the applicant's operations specifications (OPSPECS). 3. BACKGROUND. The purpose of this AC is to take advantage of technological improvements in the operational capabilities of autopilot systems, particularly at lower altitudes. This AC complements a rule change that would allow the use of an autopilot, certificated and operationally approved by the FAA, at altitudes less than 500 feet above ground level in the vertical plane and in accordance with sections 121.189 and 135.367, in the lateral plane. 4. DEFINITIONS. a. Airplane Flight Manual (AFM). A document (under 14 CFR part 25, section 25.1581) which is used to obtain an FAA type certificate. -

Digital Fly-By-Wire

TF-2001-02 DFRC Digital Fly-By-Wire "The All-Electric Airplane" Skies around the world are being filled with a new generation of military and commercial aircraft, and the majority of them are beneficiaries of one of the most significant and successful research programs conducted by NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center -- the Digital Fly-By-Wire flight control system. The Dryden DFBW program has changed the way commercial and military aircraft are designed and flown. Aircraft with fly-by- wire systems are safer, more reliable, easier to fly, more NASA F-8 modified to test a digital fly-by-wire flight control system. maneuverable and fuel NASA Photo ECN 3276 efficient, and maintenance costs are reduced. Flight control systems link pilots in their cockpits with moveable control surfaces out on the wings and tails. These control surfaces give aircraft directional movement to climb, bank, turn, and descend. Since the beginning of controlled flight in the early 1900s, wires, cables, bellcranks, and pushrods were the traditional means of connecting the control surfaces to the control sticks and rudder pedals in the cockpits. As aircraft grew in weight and size, hydraulic mechanisms were added as boosters because more power was needed to move the controls. The Digital Fly-By-Wire (DFBW) program, flown from 1972 to 1985, proved that an electronic flight control system, teamed with a digital computer, could successfully replace mechanical control systems. 1 Electric wires are the linkage between the cockpit automatically compensates -- as many as 40 and control surfaces on a DFBW aircraft. Command commands a second -- to keep the aircraft in a stable signals from the cockpit are processed by the digital environment. -

A Historical Overview of Flight Flutter Testing

tV - "J -_ r -.,..3 NASA Technical Memorandum 4720 /_ _<--> A Historical Overview of Flight Flutter Testing Michael W. Kehoe October 1995 (NASA-TN-4?20) A HISTORICAL N96-14084 OVEnVIEW OF FLIGHT FLUTTER TESTING (NASA. Oryden Flight Research Center) ZO Unclas H1/05 0075823 NASA Technical Memorandum 4720 A Historical Overview of Flight Flutter Testing Michael W. Kehoe Dryden Flight Research Center Edwards, California National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Management Scientific and Technical Information Program 1995 SUMMARY m i This paper reviews the test techniques developed over the last several decades for flight flutter testing of aircraft. Structural excitation systems, instrumentation systems, Maximum digital data preprocessing, and parameter identification response algorithms (for frequency and damping estimates from the amplltude response data) are described. Practical experiences and example test programs illustrate the combined, integrated effectiveness of the various approaches used. Finally, com- i ments regarding the direction of future developments and Ii needs are presented. 0 Vflutte r Airspeed _c_7_ INTRODUCTION Figure 1. Von Schlippe's flight flutter test method. Aeroelastic flutter involves the unfavorable interaction of aerodynamic, elastic, and inertia forces on structures to and response data analysis. Flutter testing, however, is still produce an unstable oscillation that often results in struc- a hazardous test for several reasons. First, one still must fly tural failure. High-speed aircraft are most susceptible to close to actual flutter speeds before imminent instabilities flutter although flutter has occurred at speeds of 55 mph on can be detected. Second, subcritical damping trends can- home-built aircraft. In fact, no speed regime is truly not be accurately extrapolated to predict stability at higher immune from flutter. -

Fast 49 Airbus Technical Magazine Worthiness Fast 49 January 2012 4049July 2007

JANUARY 2012 FLIGHT AIRWORTHINESS SUPPORT 49 TECHNOLOGY FAST AIRBUS TECHNICAL MAGAZINE FAST 49 FAST JANUARY 2012 4049JULY 2007 FLIGHT AIRWORTHINESS SUPPORT TECHNOLOGY Customer Services Events Spare part commonality Ensuring A320neo series commonality 2 with the existing A320 Family AIRBUS TECHNICAL MAGAZINE Andrew James MASON Publisher: Bruno PIQUET Graham JACKSON Editor: Lucas BLUMENFELD Page layout: Quat’coul Biomimicry Cover: Radio Altimeters When aircraft designers learn from nature 8 Picture from Hervé GOUSSE ExM Company Denis DARRACQ Authorization for reprint of FAST Magazine articles should be requested from the editor at the FAST Magazine e-mail address given below Radio Altimeter systems Customer Services Communications 15 Tel: +33 (0)5 61 93 43 88 Correct maintenance practices Fax: +33 (0)5 61 93 47 73 Sandra PREVOT e-mail: [email protected] Printer: Amadio Ian GOODWIN FAST Magazine may be read on Internet http://www.airbus.com/support/publications ELISE Consulting Services under ‘Quick references’ ILS advanced simulation technology 23 ISSN 1293-5476 Laurent EVAIN © AIRBUS S.A.S. 2012. AN EADS COMPANY Jean-Paul GENOTTIN All rights reserved. Proprietary document Bruno GUTIERRES By taking delivery of this Magazine (hereafter “Magazine”), you accept on behalf of your company to comply with the following. No other property rights are granted by the delivery of this Magazine than the right to read it, for the sole purpose of information. The ‘Clean Sky’ initiative This Magazine, its content, illustrations and photos shall not be modified nor Setting the tone 30 reproduced without prior written consent of Airbus S.A.S. This Magazine and the materials it contains shall not, in whole or in part, be sold, rented, or licensed to any Axel KREIN third party subject to payment or not. -

Radio Altimeter Industry Coalition Coalition Overview David Silver, Aerospace Industries Association

Radio Altimeter Industry Coalition Coalition Overview David Silver, Aerospace Industries Association 7/1/2021 2 Background • The aviation industry, working through a multi-stakeholder group formed after open, public invitation by RTCA, conducted a study to determine interference threshold to radio altimeters • The study found that 5G systems operating in the 3.7-3.98 GHz band will cause harmful interference altimeter systems operating in the 4.2- 4.4 GHz band – and in some cases far exceed interference thresholds • Harmful interference has the serious potential to impact public and aviation safety, create delays in aircraft operations, and prevent operations responding to emergency situations 7/1/2021 3 Goals and Way Forward • To ensure the safety of the public and aviation community, government, manufacturers, and operators must work together to: • Further refine the full scope of the interference threat • Determine operational environments affected • Identify technical solutions that will resolve interference issues • Develop future standards • Government needs to bring the telecom and aviation industries to the table to refine understanding of the extent of the problem and collaboratively develop mitigations to address the changing spectrum environment near-, mid-, and long- term. 7/1/2021 4 Coalition Tech-Ops Presentation John Shea, Helicopter Association International Sai Kalyanaraman, Ph.D., Collins Aerospace 7/1/2021 5 What is a Radar Altimeter? • Radar altimeters are the only device on the aircraft that can directly measure the distance between the aircraft and the ground and only operate in 4200-4400 MHz • Operate when the aircraft is on the surface to over 2500’ above ground Radar Altimeter Antennas Radar Altimeter Antennas Photo credit: Honeywell Photo credit: ALPA 7/1/2021 6 How Does a Radar Altimeter Work? 1.