A Historical Overview of Flight Flutter Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

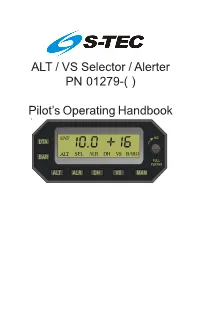

ALT / VS Selector/Alerter

ALT / VS Selector / Alerter PN 01279-( ) Pilot’s Operating Handbook ENT ALT SEL ALR DH VS BARO S–TEC * Asterisk indicates pages changed, added, or deleted by List of Effective Pages current revision. Retain this record in front of handbook. Upon receipt of a Record of Revisions revision, insert changes and complete table below. Revision Number Revision Date Insertion Date/Initials 1st Ed. Oct 26, 00 2nd Ed. Jan 15, 08 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 i S–TEC Page Intentionally Blank ii 3rd Ed. Jun 24, 16 S–TEC Table of Contents Sec. Pg. 1 Overview...........................................................................................................1–1 1.1 Document Organization....................................................................1–3 1.2 Purpose..............................................................................................1–3 1.3 General Control Theory....................................................................1–3 1.4 Block Diagram....................................................................................1–4 2 Pre-Flight Procedures...................................................................................2–1 2.1 Pre-Flight Test....................................................................................2–3 3 In-Flight Procedures......................................................................................3–1 3.1 Selector / Alerter Operation..............................................................3–3 3.1.1 Data Entry.............................................................................3–3 -

How Doc Draper Became the Father of Inertial Guidance

(Preprint) AAS 18-121 HOW DOC DRAPER BECAME THE FATHER OF INERTIAL GUIDANCE Philip D. Hattis* With Missouri roots, a Stanford Psychology degree, and a variety of MIT de- grees, Charles Stark “Doc” Draper formulated the basis for reliable and accurate gyro-based sensing technology that enabled the first and many subsequent iner- tial navigation systems. Working with colleagues and students, he created an Instrumentation Laboratory that developed bombsights that changed the balance of World War II in the Pacific. His engineering teams then went on to develop ever smaller and more accurate inertial navigation for aircraft, submarines, stra- tegic missiles, and spaceflight. The resulting inertial navigation systems enable national security, took humans to the Moon, and continue to find new applica- tions. This paper discusses the history of Draper’s path to becoming known as the “Father of Inertial Guidance.” FROM DRAPER’S MISSOURI ROOTS TO MIT ENGINEERING Charles Stark Draper was born in 1901 in Windsor Missouri. His father was a dentist and his mother (nee Stark) was a school teacher. The Stark family developed the Stark apple that was popular in the Midwest and raised the family to prominence1 including a cousin, Lloyd Stark, who became governor of Missouri in 1937. Draper was known to his family and friends as Stark (Figure 1), and later in life was known by colleagues as Doc. During his teenage years, Draper enjoyed tinkering with automobiles. He also worked as an electric linesman (Figure 2), and at age 15 began a liberal arts education at the University of Mis- souri in Rolla. -

Albatross Can Soar at Sea for Days and Even Weeks at a Time

Executive Summary April 28, 2021 Sean Berger • Ryan Casterline • Jonathan Detwiler • Joshua Forrest Zackary Long • JR Sciple • Daniel Szallai • Xinpeng Zhao Introduction Out in the remote costal cliffs of the North Pacific Ocean, the Great Albatross can soar at sea for days and even weeks at a time. With a wingspan of more than 10 feet, this magnificent bird can stay aloft for free by utilizing dynamic soaring. Its maneuverability and flight longevity allow it to be unrivaled by any other sea bird. Inspired by this bird, the aerospace engineering undergraduate team from Penn State University designed the UQ-9 Albatross: an autonomous medical supply delivery VTOL aircraft in response to the 2020- 2021 VFS Student Design Competition sponsored by Boeing. Albatross is a hybrid 4-bladed quad rotor VTOL aircraft with folding wing capabilities, designed to deliver packages at high speed to local delivery centers and logistics sites. Its variable geometry and autonomous, compact package unloading system makes it an effective delivery vehicle. It was also designed to be multiply redundant to maximize safety. These features allow Albatross to operate in environments that are void of conventional runwayswith the advantagesof a fixed wing aircraft. Vehicle Overview The Albatross is a cargo aircraft that is capable of vertical takeoff and landing during the Fall semester. Our group decided upon a vehicle that changes the configuration of its wings between vertical and horizontal flight. The folding wing concept is a design that attempts to trade‐off the advantages and disadvantages of a conventional vertical take‐off and landing vehicle with a conventional fixed‐wing aircraft configuration. -

Introduction to Aircraft Aeroelasticity and Loads

JWBK209-FM-I JWBK209-Wright November 14, 2007 2:58 Char Count= 0 Introduction to Aircraft Aeroelasticity and Loads Jan R. Wright University of Manchester and J2W Consulting Ltd, UK Jonathan E. Cooper University of Liverpool, UK iii JWBK209-FM-I JWBK209-Wright November 14, 2007 2:58 Char Count= 0 Introduction to Aircraft Aeroelasticity and Loads i JWBK209-FM-I JWBK209-Wright November 14, 2007 2:58 Char Count= 0 ii JWBK209-FM-I JWBK209-Wright November 14, 2007 2:58 Char Count= 0 Introduction to Aircraft Aeroelasticity and Loads Jan R. Wright University of Manchester and J2W Consulting Ltd, UK Jonathan E. Cooper University of Liverpool, UK iii JWBK209-FM-I JWBK209-Wright November 14, 2007 2:58 Char Count= 0 Copyright C 2007 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (+44) 1243 770620. -

Final Report RL 2017:10E

Final report RL 2017:10e Serious incident after take-off from Gothenburg/Landvetter Airport on 7 November 2016 involving SE-DSV an aeroplane of the model AVRO-RJ 100, operated by Braathens Regional Aviation AB. File no. L-112/16 7 December 2017 RL 2017:10e SHK investigates accidents and incidents from a safety perspective. Its investigations are aimed at preventing a similar event from occurring in the future, or limiting the effects of such an event. The investigations do not deal with issues of guilt, blame or liability for damages. The report is also available on SHK´s web site: www.havkom.se ISSN 1400-5719 This document is a translation of the original Swedish report. In case of discrepancies between this translation and the Swedish original text, the Swedish text shall prevail in the interpretation of the report. Photos and graphics in this report are protected by copyright. Unless other- wise noted, SHK is the owner of the intellectual property rights. With the exception of the SHK logo, and photos and graphics to which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Sweden license. This means that it is allowed to copy, distribute and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The SHK preference is that you attribute this publication using the following wording: “Source: Swedish Accident Investigation Authority”. Where it is noted in the report that a third party holds copyright to photos, graphics or other material, that party’s consent is needed for reuse of the material. -

CHAPTER TWO - Static Aeroelasticity – Unswept Wing Structural Loads and Performance 21 2.1 Background

Static aeroelasticity – structural loads and performance CHAPTER TWO - Static Aeroelasticity – Unswept wing structural loads and performance 21 2.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 21 2.1.2 Scope and purpose ....................................................................................................................... 21 2.1.2 The structures enterprise and its relation to aeroelasticity ............................................................ 22 2.1.3 The evolution of aircraft wing structures-form follows function ................................................ 24 2.2 Analytical modeling............................................................................................................... 30 2.2.1 The typical section, the flying door and Rayleigh-Ritz idealizations ................................................ 31 2.2.2 – Functional diagrams and operators – modeling the aeroelastic feedback process ....................... 33 2.3 Matrix structural analysis – stiffness matrices and strain energy .......................................... 34 2.4 An example - Construction of a structural stiffness matrix – the shear center concept ........ 38 2.5 Subsonic aerodynamics - fundamentals ................................................................................ 40 2.5.1 Reference points – the center of pressure..................................................................................... 44 2.5.2 A different -

Installation Manual, Document Number 200-800-0002 Or Later Approved Revision, Is Followed

9800 Martel Road Lenoir City, TN 37772 PPAAVV8800 High-fidelity Audio-Video In-Flight Entertainment System With DVD/MP3/CD Player and Radio Receiver STC-PMA Document P/N 200-800-0101 Revision 6 September 2005 Installation and Operation Manual Warranty is not valid unless this product is installed by an Authorized PS Engineering dealer or if a PS Engineering harness is purchased. PS Engineering, Inc. 2005 © Copyright Notice Any reproduction or retransmittal of this publication, or any portion thereof, without the expressed written permission of PS Engi- neering, Inc. is strictly prohibited. For further information contact the Publications Manager at PS Engineering, Inc., 9800 Martel Road, Lenoir City, TN 37772. Phone (865) 988-9800. Table of Contents SECTION I GENERAL INFORMATION........................................................................ 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 SCOPE ............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 EQUIPMENT DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................... 1-1 1.4 APPROVAL BASIS (PENDING) ..................................................................................... 1-1 1.5 SPECIFICATIONS......................................................................................................... 1-2 1.6 EQUIPMENT SUPPLIED ............................................................................................ -

Introduction to Aeroelasticity.Pdf

Aeroelasticity Dr. Ugur GUVEN Aerospace Engineer (P.hD) Nuclear Science and Technology Engineer (M.Sc) What is Aeroelasticity • Aeroelasticity is broadly defined as the interaction between the aerodynamic forces and the structural forces causing a deformation in the structure of the aerospace craft as well as in its control mechanism or in its propulsion systems. Importance of Aeroelasticity • Aeroelasticity has become a very important force especially after the 1950’s. • The interaction between aerodynamic loads and structural deformations have gained great importance in view of factors related to the design of aircraft as well as missiles. • Aeroelasticity plays at least some part on fuel sloshing as well as on the reentry of spacecraft in astronautics. Trends in Technology • Due to the advancements in technology, it has become quite common to see the slenderness ratio (ratio of length of wing span to thickness at the root) increase. • The wing span area as well as the length of aircrafts have increased causing aircraft to become much more susceptible to interaction between structural loads and aerodynamic loads Slenderness Ratio Effect of Aerodynamic Loads • The forces of lift and drag as well as torsion moment will have some sort of effect on the structural integrity of the spacecraft. • In many cases, some parts of aircraft or spacecraft may bend or ripple slightly due to these loads. • The frequency of these loads and effects can also cause the aircraft’s structure to suffer from metal fatigue in the long run. Scope of Aeroelasticity Vibration • One of the ways in which aerodynamic and structural forces collide with each other is through vibration. -

Glider Handbook, Chapter 2: Components and Systems

Chapter 2 Components and Systems Introduction Although gliders come in an array of shapes and sizes, the basic design features of most gliders are fundamentally the same. All gliders conform to the aerodynamic principles that make flight possible. When air flows over the wings of a glider, the wings produce a force called lift that allows the aircraft to stay aloft. Glider wings are designed to produce maximum lift with minimum drag. 2-1 Glider Design With each generation of new materials and development and improvements in aerodynamics, the performance of gliders The earlier gliders were made mainly of wood with metal has increased. One measure of performance is glide ratio. A fastenings, stays, and control cables. Subsequent designs glide ratio of 30:1 means that in smooth air a glider can travel led to a fuselage made of fabric-covered steel tubing forward 30 feet while only losing 1 foot of altitude. Glide glued to wood and fabric wings for lightness and strength. ratio is discussed further in Chapter 5, Glider Performance. New materials, such as carbon fiber, fiberglass, glass reinforced plastic (GRP), and Kevlar® are now being used Due to the critical role that aerodynamic efficiency plays in to developed stronger and lighter gliders. Modern gliders the performance of a glider, gliders often have aerodynamic are usually designed by computer-aided software to increase features seldom found in other aircraft. The wings of a modern performance. The first glider to use fiberglass extensively racing glider have a specially designed low-drag laminar flow was the Akaflieg Stuttgart FS-24 Phönix, which first flew airfoil. -

Using an Autothrottle to Compare Techniques for Saving Fuel on A

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2010 Using an autothrottle ot compare techniques for saving fuel on a regional jet aircraft Rebecca Marie Johnson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Rebecca Marie, "Using an autothrottle ot compare techniques for saving fuel on a regional jet aircraft" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11358. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11358 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Using an autothrottle to compare techniques for saving fuel on A regional jet aircraft by Rebecca Marie Johnson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Electrical Engineering Program of Study Committee: Umesh Vaidya, Major Professor Qingze Zou Baskar Ganapathayasubramanian Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2010 Copyright c Rebecca Marie Johnson, 2010. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION I gratefully acknowledge everyone who contributed to the successful completion of this research. Bill Piche, my supervisor at Rockwell Collins, was supportive from day one, as were many of my colleagues. I also appreciate the efforts of my thesis committee, Drs. Umesh Vaidya, Qingze Zou, and Baskar Ganapathayasubramanian. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Problems of High Speed and Altitude Robert Stengel, Aircraft Flight Dynamics MAE 331, 2018

12/14/18 Problems of High Speed and Altitude Robert Stengel, Aircraft Flight Dynamics MAE 331, 2018 Learning Objectives • Effects of air compressibility on flight stability • Variable sweep-angle wings • Aero-mechanical stability augmentation • Altitude/airspeed instability Flight Dynamics 470-480 Airplane Stability and Control Chapter 11 Copyright 2018 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE331.html 1 http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/FlightDynamics.html Outrunning Your Own Bullets • On Sep 21, 1956, Grumman test pilot Tom Attridge shot himself down, moments after this picture was taken • Test firing 20mm cannons of F11F Tiger at M = 1 • The combination of events – Decay in projectile velocity and trajectory drop – 0.5-G descent of the F11F, due in part to its nose pitching down from firing low-mounted guns – Flight paths of aircraft and bullets in the same vertical plane – 11 sec after firing, Attridge flew through the bullet cluster, with 3 hits, 1 in engine • Aircraft crashed 1 mile short of runway; Attridge survived 2 1 12/14/18 Effects of Air Compressibility on Flight Stability 3 Implications of Air Compressibility for Stability and Control • Early difficulties with compressibility – Encountered in high-speed dives from high altitude, e.g., Lockheed P-38 Lightning • Thick wing center section – Developed compressibility burble, reducing lift-curve slope and downwash • Reduced downwash – Increased horizontal stabilizer effectiveness – Increased static stability – Introduced -

ICE PROTECTION Incomplete

ICE PROTECTION GENERAL The Ice and Rain Protection Systems allow the aircraft to operate in icing conditions or heavy rain. Aircraft Ice Protection is provided by heating in critical areas using either: Hot Air from the Pneumatic System o Wing Leading Edges o Stabilizer Leading Edges o Engine Air Inlets Electrical power o Windshields o Probe Heat . Pitot Tubes . Pitot Static Tube . AOA Sensors . TAT Probes o Static Ports . ADC . Pressurization o Service Nipples . Lavatory Water Drain . Potable Water Rain removal from the Windshields is provided by two fully independent Wiper Systems. LEADING EDGE THERMAL ANTI ICE SYSTEM Ice protection for the wing and horizontal stabilizer leading edges and the engine air inlet lips is ensured by heating these surfaces. Hot air supplied by the Pneumatic System is ducted through perforated tubes, called Piccolo tubes. Each Piccolo tube is routed along the surface, so that hot air jets flowing through the perforations heat the surface. Dedicated slots are provided for exhausting the hot air after the surface has been heated. Each subsystem has a pressure regulating/shutoff valve (PRSOV) type of Anti-icing valve. An airflow restrictor limits the airflow rate supplied by the Pneumatic System. The systems are regulated for proper pressure and airflow rate. Differential pressure switches and low pressure switches monitor for leakage and low pressures. Each Wing's Anti Ice System is supplied by its respective side of the Pneumatic System. The Stabilizer Anti Ice System is supplied by the LEFT side of the Pneumatic System. The APU cannot provide sufficient hot air for Pneumatic Anti Ice functions.