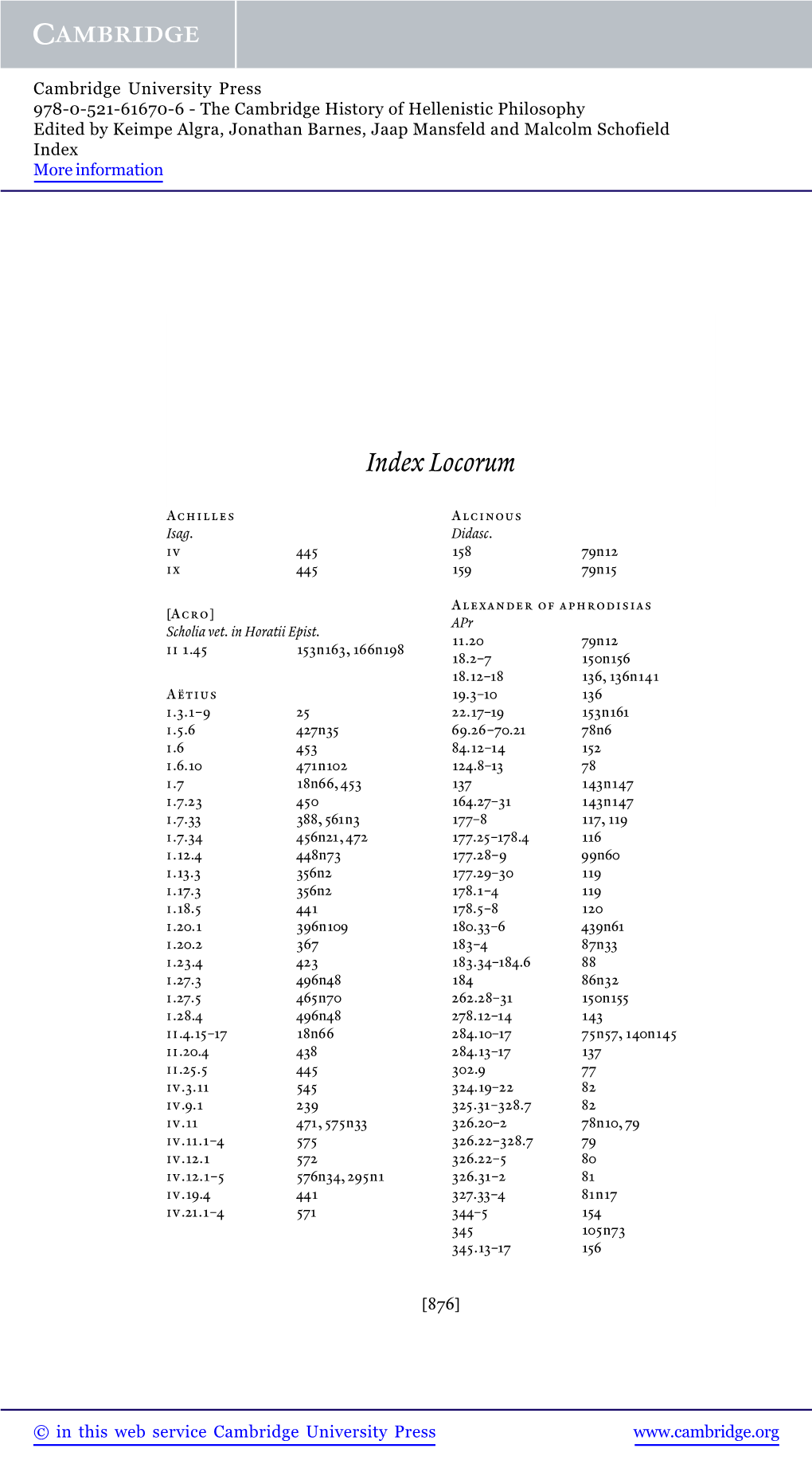

Index Locorum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download the Pig of Happiness Ebook

THE PIG OF HAPPINESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward Monkton | 32 pages | 15 Jan 2004 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007177981 | English | London, United Kingdom The Pig of Happiness PDF Book Our guest practices…. Plato c. It was extremely discouraging and took a few days to recover from, although it was mostly by ego that was injured. I knew Edward Monkton was going to be a success when people started e-mailing me daily saying that it touched their hearts, it made them think, and most important, it made them laugh out loud-again and again. Views Read Edit View history. Philosopher Wisdom Women in philosophy. Necessary Necessary. Jun 20, Connie rated it it was amazing. It gave me a distraction from excel spreadsheets anyway! Aristotle's Psychology. Great read!!! Read more Oct 16, Michelle rated it it was amazing. Augustine follows the Neoplatonic tradition in asserting that happiness lays in the contemplation of the purely intelligible realm. Import charges. One aid to achieving happiness is the tetrapharmakos or the four-fold cure:. Zalta ed. I was disappointed because how was I going to run with a twisted knee? Apr 26, Ronald Boy rated it it was amazing. Feb 22, Ana rated it liked it Shelves: bookcrossing. Pyrrho identified that what prevented people from attaining ataraxia was their beliefs in non- evident matters, i. Stood and read this book to a friend in Barnes and Noble. Our guest,…. Show More Show Less. Thanks for reading. He claims that it is better to be a dissatisfied unhappy person than it is to be a satisfied pig. -

The Place of Ethics in Aristotle's Philosophy

Offprint from OXFORDSTUDIES INANCIENT PHILOSOPHY EDITOR:BRADINWOOD VOLUMEXL Essays in Memory of Michael Frede JAMESALLEN EYJÓLFURKJALAREMILSSON WOLFGANG-RAINERMANN BENJAMINMORISON 3 THEPLACEOFETHICSIN ARISTOTLE’SPHILOSOPHY GEORGEKARAMANOLIS . The issue D the wealth of studies on Aristotle’s ethics, there has been almost nothing, as far as I know, dedicated to considering the place that ethics occupies in Aristotle’s philosophy. This issue does not seem to be interesting to modern students of Aristotle. There was, however, a debate and indeed a controversy about this issue in late antiquity, as I shall show in this paper. There are two questions in- volved here, which are interrelated, and the debate was about both of them. The first concerns the order in which ethics or practical philosophy, more generally, must be studied by the student of Aris- totle’s philosophy. The second concerns the relative significance of this part of philosophy within the framework of Aristotle’s philoso- phical work. Both questions arise from remarks that Aristotle himself makes. The second in particular, some might argue, is addressed by Aris- totle in various parts of his work. In Metaphysics Ε –, for instance, he famously discusses the relative value of theoretical, practical, and productive sciences. Aristotle there argues explicitly that the the- oretical sciences are preferable (hairetōterai) to all others, practical © George Karamanolis It is a pleasure to offer this contribution in honour of Michael Frede, who taught me so much. Drafts of this paper were presented at Princeton, Oxford, and the Department of Theory and Philosophy of Science, University of Athens. I have benefited from the comments of all these audiences. -

Aspasian Infidelities. on Aspasius' Philosophical Background (EN I)

apeiron 2016; 49(2): 229–259 António Pedro Mesquita* Aspasian Infidelities. On Aspasius’ Philosophical Background (EN I) DOI 10.1515/apeiron-2015-0028 Abstract: The discussion on Aspasius’ philosophical background has benefited in recent years from a wide consensus. According to this consensus, Aspasius should be regarded as a Peripatetic, or even as an “orthodox Peripatetic” (Barnes’ phrase). It is true that Aspasius’ commentary is generally in tune with Aristotle. It is true that he shows an extensive knowledge of Aristotelian research pertinent for the discussions and that he uses Aristotelian concepts, principles, and doctrines with ease as if they were his own, thus denoting an old assimila- tion of those materials and a long accommodation to them. In a word, it is true that Aspasius is an Aristotelian. He is, however, as I will try to show in this paper, an Aristotelian strongly influenced by Stoicism. I will do so by selecting those points from Aspasius’ commentary on book I of the Nicomachean Ethics where the Stoic influence is most flagrantly evident, namely in his interpretation of art (τέχνη), his conception of continence and incontinence and, especially, his interpretation of the relation between happiness, virtue, and external goods in Aristotle. Keywords: Aspasius, Aristotelianism, Stoicism, happiness, virtue, external goods The Consensus The discussion on Aspasius’ philosophical background has benefited in recent years from a wide consensus. A good example of this consensus is the position Barnes sustains on the matter in his excellent “Introduction to Aspasius”, where he states the following1: Next, Aspasius’ philosophical position. Galen calls him a Peripatetic, and it is plain that his pupil taught Galen Peripatetic philosophy. -

Aristotelianism in the First Century BC

CHAPTER 5 Aristotelianism in the First Century BC Andrea Falcon 1 A New Generation of Peripatetic Philosophers The division of the Peripatetic tradition into a Hellenistic and a post- Hellenistic period is not a modern invention. It is already accepted in antiquity. Aspasius speaks of an old and a new generation of Peripatetic philosophers. Among the philosophers who belong to the new generation, he singles out Andronicus of Rhodes and Boethus of Sidon.1 Strabo adopts a similar division. He too distinguishes between the older Peripatetics, who came immediately after Theophrastus, and their successors.2 He collectively describes the latter as better able to do philosophy in the manner of Aristotle (φιλοσοφεῖν καὶ ἀριστοτελίζειν). It remains unclear what Strabo means by doing philosophy in the manner of Aristotle.3 But he certainly thinks that the philosophers who belong to the new generation, and not those who belong to the old one, deserve the title of true Aristotelians. For Strabo, the event separating the old from the new Peripatos is the rediscovery and publication of Aristotle’s writings. We may want to resist Strabo’s negative characterization of the earlier Peripatetics. For Strabo, they were not able to engage in philosophy in any seri- ous way but were content to declaim general theses.4 This may be an unfair judgment, ultimately based on the anachronistic assumption that any serious philosophy requires engagement with an authoritative text.5 Still, the empha- sis that Strabo places on the rediscovery of Aristotle’s writings suggests that the latter were at the center of the critical engagement with Aristotle in the 1 Aspasius, On Aristotle’s Ethics 44.20–45.16. -

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM Western Pre-Socratics Fanon Heraclitus- Greek 535-475 Bayle Panta rhei Marshall Mcluhan • "Everything flows" Roman Jakobson • "No man ever steps in the same river twice" Saussure • Doctrine of flux Butler Logos Harris • "Reason" or "Argument" • "All entities come to be in accordance with the Logos" Dike eris • "Strife is justice" • Oppositional process of dissolving and generating known as strife "The Obscure" and "The Weeping Philosopher" "The path up and down are one and the same" • Theory about unity of opposites • Bow and lyre Native of Ephesus "Follow the common" "Character is fate" "Lighting steers the universe" Neitzshce said he was "eternally right" for "declaring that Being was an empty illusion" and embracing "becoming" Subject of Heideggar and Eugen Fink's lecture Fire was the origin of everything Influenced the Stoics Protagoras- Greek 490-420 BCE Most influential of the Sophists • Derided by Plato and Socrates for being mere rhetoricians "Man is the measure of all things" • Found many things to be unknowable • What is true for one person is not for another Could "make the worse case better" • Focused on persuasiveness of an argument Names a Socratic dialogue about whether virtue can be taught Pythagoras of Samos- Greek 570-495 BCE Metempsychosis • "Transmigration of souls" • Every soul is immortal and upon death enters a new body Pythagorean Theorem Pythagorean Tuning • System of musical tuning where frequency rations are on intervals based on ration 3:2 • "Pure" perfect fifth • Inspired -

Greek Medical Papyri Archiv Für Papyrusforschung Und Verwandte Gebiete

Greek Medical Papyri Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete Begründet von Ulrich Wilcken Herausgegeben von Jean-Luc Fournet Bärbel Kramer Herwig Maehler Brian McGing Günter Poethke Fabian Reiter Sebastian Richter Beiheft 40 De Gruyter Greek Medical Papyri Text, Context, Hypertext edited by Nicola Reggiani De Gruyter The present volume is published in the framework of the Project “Online Humanities Scholarship: A Digital Medical Library Based on Ancient Texts” (DIGMEDTEXT, Principal Investigator Profes- sor Isabella Andorlini), funded by the European Research Council (Advanced Grant no. 339828) at the University of Parma, Dipartimento di Lettere, Arti, Storia e Società. ISBN 978-3-11-053522-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-053640-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-053569-3 ISSN 1868-9337 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No-Derivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019948020 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2019 Nicola Reggiani, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Table of contents Introduction (Nicola Reggiani) .......................................................................... IX I. Medical Texts From Prescription to Practice: -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48147-2 — Scale, Space and Canon in Ancient Literary Culture Reviel Netz Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48147-2 — Scale, Space and Canon in Ancient Literary Culture Reviel Netz Index More Information Index Aaker, Jennifer, 110, 111 competition, 173 Abdera, 242, 310, 314, 315, 317 longevity, 179 Abel, N. H., 185 Oresteia, 197, 200, 201 Academos, 189, 323, 324, 325, 337 papyri, 15 Academy, 322, 325, 326, 329, 337, 343, 385, 391, Persians, 183 399, 404, 427, 434, 448, 476, 477–8, 512 portraits, 64 Achilles Tatius, 53, 116, 137, 551 Ptolemaic era, 39 papyri, 16, 23 Aeschylus (astronomer), 249 Acta Alexandrinorum, 87, 604 Aesop, 52, 68, 100, 116, 165 adespota, 55, 79, 81–5, 86, 88, 91, 99, 125, 192, 194, in education, 42 196, 206, 411, 413, 542, 574 papyri, 16, 23 Adkin, Neil, 782 Aethiopia, 354 Adrastus, 483 Aetia, 277 Adrastus (mathematician), 249 Africa, 266 Adrianople, 798 Agatharchides, 471 Aedesius (martyr), 734, 736 Agathocles (historian), 243 Aegae, 479, 520 Agathocles (peripatetic), 483 Aegean, 338–43 Agathon, 280 Aegina, 265 Agias (historian), 373 Aelianus (Platonist), 484 agrimensores, 675 Aelius Aristides, 133, 657, 709 Ai Khanoum, 411 papyri, 16 Akhmatova, Anna, 186 Aelius Herodian (grammarian), 713 Albertus Magnus, 407 Aelius Promotus, 583 Albinus, 484 Aenesidemus, 478–9, 519, 520 Alcaeus, 49, 59, 61–2, 70, 116, 150, 162, 214, 246, Aeolia, 479 see also Aeolian Aeolian, 246 papyri, 15, 23 Aeschines, 39, 59, 60, 64, 93, 94, 123, 161, 166, 174, portraits, 65, 67 184, 211, 213, 216, 230, 232, 331 Alcidamas, 549 commentaries, 75 papyri, 16 Ctesiphon, 21 Alcinous, 484 False Legation, 22 Alcmaeon, 310 -

The Phenomenon of Chance in Ancient Greek Thought

THE PHENOMENON OF CHANCE IN ANCIENT GREEK THOUGHT by MELISSA M. SHEW A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Philosophy and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2008 11 University of Oregon Graduate School Confirmation of Approval and Acceptance of Dissertation prepared by: Melissa Shew Title: "The Phenomenon of Chance in Ancient Greek Thought" This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree in the Department ofPhilosophy by: Peter Warnek, Chairperson, Philosophy John Lysaker, Member, Philosophy Ted Toadvine, Member, Philosophy James Crosswhite, Outside Member, English and Richard Linton, Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean ofthe Graduate School for the University of Oregon. September 6, 2008 Original approval signatures are on file with the Graduate School and the University of Oregon Libraries. 111 An Abstract of the Dissertation of Melissa M. Shew for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy to be taken September 2008 Title: THE PHENOMENON OF CHANCE IN ANCIENT GREEK THOUGHT Approved: Dr. Peter Warnek This dissertation engages three facets of Greek philosophy: 1) the phenomenon of tyche (chance, fortune, happening, or luck) in Aristotle's Physics, Nicomachean Ethics, and Poetics; 2) how tyche infonns Socrates' own philosophical practice in the Platonic dialogues; and 3) how engaging tyche in these Greek texts challenges established interpretations of Greek thought in contemporary scholarship and discussion. I argue that the complex status of tyche in Aristotle's texts, when combined with its appearance in the Platonic dialogues and the framework of Greek myth and poetry (poiesis), underscores the seriousness with which the Greeks consider the role of chance in human life. -

La Tetrapharmakos, Formule Authentique Ou Résumé Simpliste De L’Éthique Épicurienne ? Julie Giovacchini

La tetrapharmakos, formule authentique ou résumé simpliste de l’éthique épicurienne ? Julie Giovacchini To cite this version: Julie Giovacchini. La tetrapharmakos, formule authentique ou résumé simpliste de l’éthique épicuri- enne ? : Quelques éléments sur le statut des abrégés et des florilèges dans la pédagogie du Jardin. Philosophie antique - problèmes, renaissances, usages , Presses universitaires du Septentrion, 2019, pp.29-56. hal-02315259 HAL Id: hal-02315259 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02315259 Submitted on 14 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LA TETRAPHARMAKOS FORMULE AUTHENTIQUE OU RESUMÉ SIMPLISTE DE L’ÉTHIQUE ÉPICURIENNE ? Quelques éléments sur le statut des abrégés et des florilèges dans la pédagogie du Jardin Julie GIOVACCHINI CNRS UMR8230 Centre Jean Pépin RESUME. L’objet de cet article est d’analyser la version formulaire la plus connue de l’éthique épicurienne, souvent appelée dans la littérature critique tetrapharmakos ou quadruple remède. On tentera de trancher la question de l’authenticité de cette formule, et d’en déduire certains éléments concernant la pédagogie éthique épicurienne et le rôle qu’y jouent abrégés et florilèges. SUMMARY. The paper aims at analysing the best known formula of Epicurean ethics, often called in the secondary literature the tetrapharmakos (quadruple medicine). -

21-44 Epicurus' Second Remedy: “Death Is Nothing To

http://akroterion.journals.ac.za http://akroterion.journals.ac.za EPICURUS’ SECOND REMEDY: “DEATH IS NOTHING TO US” P E Bjarnason (University of Stellenbosch) Cowards die many times before their deaths; The valiant never taste of death but once. Of all the wonders that I yet have heard, It seems to me most strange that men should fear; Seeing that death, a necessary end, Will come when it will come. (Shakespeare, Julius Caesar II, ii, 32-37) That death is complete extinction is the message forcefully driven home by the Epicurean analysis of the soul as a temporary amalgam of atomic particles . The moral corollary, that you should not let the fear of death ruin your life, is a cardinal tenet of Epicurean ethics. (Long and Sedley 1987:153) The second remedy of the tetrapharmakos concerns the second of the two great fears to which man is subject: death. Frischer (1982:208) observes that the Epicureans regarded death as “more damaging to peace of mind than all other fears except fear of the gods”. The Epicurean position is stated clearly in the surviving writings of the Master, and it is necessary to go directly to the ipsissima verba as our starting point, and then to augment our understanding of Epicurus’ words with further passages from later Epicureans and other philosophers. In these writings we shall see that death, as the material dissolution of body and soul, is a process at once natural, inevitable, and final. 1. Primary Sources: Epicurus on Body, Soul, and Death The first thing which Epicurus strove to establish in his psychological theory was the complete and permanent loss of consciousness at death. -

Philosophical Vignettes at Lucretius' De Rerum Natura 2.1-13

Philosophical Vignettes at Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura 2.1-13 In a forthcoming article, Chris Eckerman offers a new interpretation of DRN 2.7-8, arguing that tenere…templa serena refers to practicing ataraxia. I am in agreement with Eckerman’s suggestion. The purpose of this talk is to consider interpretive ramifications, left unaddressed, deriving from his philological argument. I argue that Lucretius begins his proem by developing vignettes around cornerstone concepts in the Epicurean ethical doctrine. I suggest that Lucretius develops an argumentative tricolon, with two vignettes emphasizing aponia (1-2, 5-6) and one vignette emphasizing ataraxia (7-13). Scholars have already recognized that, in the proem, Lucretius develops the idea that the Epicurean life offers security (asphaleia) (cf. Konstan 2008, 32), but, since we have not recognized, until recently, that the third member of the tricolon references ataraxia, we have not recognized that Lucretius develops a tricolon dedicated specifically to reflection on aponia in the first two limbs and on ataraxia in the third. That is to say, the proem does not focus on security generally but on the security that may be had in aponia and ataraxia specifically. The first two lines provide Lucretius’ first vignette on aponia. Suave, mari magno turbantibus aequora ventis, e terra magnum alterius spectare laborem; Looking upon the great labor of another person from land when winds are upsetting the calm on the great sea is pleasant. The term laborem (2) is programmatic, for, as M. Gale (2013, 33) has shown, Lucretius uses labor and laborare to reference ‘the futile struggles of the non-Epicurean.’ Accordingly, readers, as they become familiar both with Epicurean doctrine and with Lucretius’ language, infer that the man is at sea for commercial reasons, pursuing the affluence that may result therefrom (cf. -

Lucrèce Au Féminin Au Dix-Huitième Siècle La Femme Épicurienne Et Le Discours Sur Le Bonheur D’Émilie Du Châtelet

Lucrèce au féminin au dix-huitième siècle La femme épicurienne et le Discours sur le bonheur d’Émilie du Châtelet Natania Meeker University of Southern California Traduit de l’américain par Katy Le Bris La féminité lucrétienne « Dans un certain sens, nous sommes tous épicuriens à présent » écrit Catherine Wilson dans son introduction à Epicureanism at the Origins of Modernity 1. Stephen Greenblatt fait une observation similaire dans Quattrocento, où il raconte l’histoire de la redécouverte du poème De rerum natura par le scriptor et chasseur de livres Poggio Bracciolini. Bracciolini (dit le Pogge), en mettant au jour l’œuvre de Lucrèce, enterrée dans un monastère allemand, s’est fait « le maïeuticien de la modernité » d’après Greenblatt 2. Le lecteur peut voir, dans cette expression évoquant un Lucrèce dont nous sommes tous les enfants, un nouvel écho de l’affirmation célèbre de Denis Diderot dans l’article « épicu- réisme ou épicurisme » de l’Encyclopédie, selon laquelle « on se fait stoïcien mais on naît épicurien » 3. Des épicuriens, voilà ce que nous, modernes, sommes destinés à être. Et, pour Diderot, c’est pendant le siècle des Lumières que nous nous sommes pleinement éveillés à nos origines épicuriennes. 1 Catherine Wilson, Epicureanism at the Origins of Modernity, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 3. 2 Stephen Greenblatt, Quattrocento, trad. Cécile Arnaud, Paris, Flammarion, 2015, p. 21. En anglais dans la version originale, « maïeuticien » devient “mid-wife” (sage-femme). 3 Denis Diderot, « épicuréisme ou épicurisme » dans Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc., éd. Denis Diderot et Jean le Rond d’Alembert, University of Chicago : ARTFL Encyclopédie Project (Autumn 2017 Edition), Robert Morrissey and Glenn Roe (eds), http://encyclopedie.uchicago.edu/, tome V, p.