A Political History of Chess in the Soviet Union, 1917-1948

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Chess Federation P.O.Box 66511, Al-Ain, UAE, [email protected] Tel: +971-3-7633387, Fax: 7633362 URL

Asian Chess Federation P.O.Box 66511, Al-Ain, UAE, [email protected] Tel: +971-3-7633387, Fax: 7633362 URL: www.asianchess.com Continental Assembly 2-3 October 2018 Batumi, Georgia Minutes 0.1 Obituaries IA Giam Choo Kwee, Singapore Mr. G.S. Dissanayake – Former President of Sri Lanka Chess Federation IA, IO Peter W. Stuart (NZL) - Former President of New Zealand Chess Federation 0.2 Roll Call President: Sheikh Sultan bin Khalifah Al Nahyan (UAE) Deputy President: Bharat Singh (IND) Secretary General: Hisham Al Taher (UAE) Vice President: Abigail Tian Hongwei (CHN) Treasurer: Mehrdad Pahlevanzadeh (IRI) AFG Mohibi, Abasin MGL Sainbayar, Tserendorj AUS Bonham, Kevin MYA Maung Maung Lwin BAN Syed Shahab Udin NRU Proxy to Nikos Kalesis (SOL) BHU Proxy to D.V. Sundar (IND) NEP Shrestha, Eka Lal BRU Ali, Zainal Abidin NZL Spiller, Paul CAM Dy, Chaut OMA Azza Al Habsi CHN Tian, Hongwei PAK Proxy to Eka L.Shrestha (NEP) TPE Chan, Mei Fang Dina PLW Whipps, Eric Ksayu Surangel FIJ Proxy to Eric Whipps (PLW) PLE Al Susi, Rajai GUM Orio, Jocelyn A PNG Skeha, Craig HKG Chan, Kwai Keong PHI Canobas, Raul / Abundo, Casto IND Sundar, Damal Villivalam QAT Al Mudahka, Mohd INA Ambarukmi, Dwi Hatmisari KSA Proxy to Sami Khader (JOR) IRI Kambouzia, Mohammad Jafar SGP Nisban, Jasmin IRQ Dhafer, Abdul A. Madhloom SOL Kalesis, Nikolaos JPN Proxy to Jamie Kenmure(NRU) KOR Hyun In Suk, Jinwoo Song JOR Khader, Sami SRI Wijesuriya, G. Luxman KAZ Balgabaev, Berik SYR Abbas, Ali KUW Alamiri, Adel TJK Vatanov, Khurshed KGZ Turpanov, Milan THA Nakvanich, Sahapol LBN Kraytem, Ezat TKM Nazarov, Rasul MAC Silveirinha, Jose Antonio C. -

Recovering and Rendering Vital Blueprint for Counter Education At

Recovering and Rendering Vital clash that erupted between the staid, conservative Board of Trustees and the raucous experimental work and atti- Blueprint for Counter Education tudes put forth by students and faculty (the latter often- times more militant than the former). The full story of the at the California Institute of the Arts Institute during its frst few years requires (and deserves) an entire book,8 but lines from a 1970 letter by Maurice Paul Cronin Stein, founding Dean of the School of Critical Studies, written a few months before the frst students arrived on campus, gives an indication of the conficts and delecta- tions to come: “This is the most hectic place in the world at the moment and promises to become even more so. At heart of the California Institute of Arts’ campus is We seem to be testing some complex soap opera prop- a vast, monolithic concrete building, containing more osition about the durability of a marriage between the than a thousand rooms. Constructed on a sixty-acre site radical right and left liberals. My only way of adjusting to thirty-fve miles north of Los Angeles, it is centered in the situation is to shut my eyes, do my job, and hope for what at the end of the 1960s was the remote outpost the best.”9 of sun-scorched Valencia (a town “dreamed up by real estate developers to receive the urban sprawl which is • • • Los Angeles”),1 far from Hollywood, a town that was—for many students at the Institute—the belly of the beast. -

Game Room Tables 2020 Game Room Tables

Game Room Tables 2020 Game Room Tables At SilverLine, our goal is to build fine furniture that will be a family heirloom – for your family and your children’s families, in the old world tradition of our ancestors. Manufactured with quality North American hardwoods, our pool tables and game tables are handcrafted and constructed for years of play. We have several styles and sizes available. Can’t find the perfect table or accessory? Let us create a piece of furniture just for you! Pool tables feature: • 1" framed slate • 22oz. cloth in over 20 colors • 12 pocket choices • Available in 7', 8', or 9' lengths Our tables are available in many custom finishes, or we can match your existing furniture. SILVERLINE, INC 2 game room furniture | 2020 Index POOL TABLES Breckenridge ................................................. 4 CHESS TABLES Caldwell ........................................................ 4 Allendale Chess Table ................................... 14 Caledonia ....................................................... 5 Ashton Chess Table ....................................... 14 Classic Mission ............................................... 5 Landmark Mission ......................................... 6 FOOSBALL Monroe .......................................................... 6 Alpine Foosball Table ................................... 15 Regal ............................................................. 7 Signature Mission Foosball Table .................. 15 Shaker Hill .................................................... 7 -

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

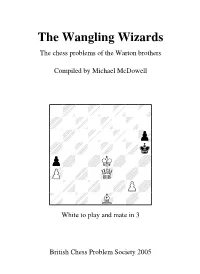

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

Montenegro Chess Festival

Montenegro Chess Festival 2 IM & GM Round Robin Tournaments, 26.02-18.03.2021. Festival Schedule: Chess Club "Elektroprivreda" and Montenegro Chess Federation organizing Montenegro Chess Festival from 26th February to 18th March 2021. Festival consists 3 round robin tournaments as follows: 1. IM Round Robin 2021/01 - Niksic 26th February – 4th March 2. IM Round Robin 2021/02 - Niksic 5th March – 11th March 3. GM Round Robin 2021/01 - Podgorica 12th March – 18th March Organizer will provide chess equipment for all events, games will be broadcast online. Winners of all tournaments receive trophy. You can find Information about tournaments on these links: IM Round Robin 2021/01 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549103.aspx?lan=1 IM Round Robin 2021/02 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549104.aspx?lan=1 GM Round Robin 2021/01 - https://chess-results.com/tnr549105.aspx?lan=1 Health protection measures will be applied according to instructions from Montenegro institutions and will be valid during the tournament duration. Masks are obligatory all the time, safe distance will be provided between the boards. Organizer are allowed to cancel some or all events in the festival if situation with pandemic requests events to be cancelled. Tournaments Description: Round Robin tournaments are closed tournaments with 10 participants each and will be valid for international chess title norms. Drawing of lots and Technical Meeting for each event will be held at noon on the starting day of each tournament. Minimal guaranteed average rating of opponents on GM tournament is 2380 and 2230 on IM tournament. Playing schedule: For all three tournaments, double rounds will be played second and third day. -

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1 “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION 2013, Botswana Chess Review In this Issue; BY: KEENESE NEOYAME KATISENGE 1. Historic World Chess Federation’s Visit to Botswana 2. Field Performance 3. Administration & Developmental Programs BCF PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTOR 4. Social Responsibility, Marketing and Publicity / Sponsorships B “Checkmate” is the first edition of BCF e-Newsletter. It will be released on a quarterly basis with a review of chess events for the past period. In Chess circles, “Checkmate” announces the end of the game the same way this newsletter reviews performance at the end of a specified period. The aim of “Checkmate” is to maintain contact with all stakeholders, share information with interesting chess highlights as well as increase awareness in a BNSC Chair Solly Reikeletseng,Mr Mogotsi from Debswana, cost-effective manner. Mr Bobby Gaseitsewe from BNSC and BCF Exo during The 2013 Re-ba bona-ha Youth Championships 2013, Botswana Chess Review Under the leadership of the new president, Tshenolo Maruatona,, Botswana Chess continues to steadily Minister of Youth, Sports & Culture Hon. Shaw Kgathi and cement its place as one of the fastest growing the FIDE Delegation during their visit to Botswana in 2013 sporting codes in the country. BCF has held a number of activities aimed at developing and growing the sport in the country. “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION | Issue 1 2 2013 Review Cont.. The president of the federation, Mr Maruatona attended two key International Congresses, i.e Zonal Meeting held during The -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

3 After the Tournament

Important Dates for 2018-19 Important Changes early Sept. Chess Manual & Rule Book posted online TERMS & CONDITIONS November 1 Preliminary list of entries posted online V-E-3 Removes all restrictions on pairing teams at the state December 1 Official Entry due tournament. The result will be that teams from the same Official Entry should be submitted online by conference may be paired in any round. your school’s official representative. V- E-6 Provides that sectional tournament will only be paired There is no entry fee, but late entries will incur after registration is complete so that last-minute with- a $100 late fee. drawals can be taken into account. December 1 Updated list of entries posted online IX-G-4 Clarifies that the use of a smartwatch by a player is ille- gal, with penalties similar to the use of a cell phone. December 1 List of Participants form available online Contact your activities director for your login ID and password. VII-C-1,4,5,6 and VIII-D-1,2,4 Failure to fill out this form by the deadline con- Eliminates individual awards at all levels of the stitutes withdrawal from the tournament. tournament. Eliminates the requirement that a player stay on one board for the entire tournament. Allows January 2 Required rules video posted players to shift up and down to a different board, while January 16 Deadline to view online rules presentation remaining in the "Strength Order" declared by the Deadline to submit List of Participants (final coach prior to the start of the tournament. -

Grandmaster Repertoire 11: Beating 1.D4 Sidelines Pdf, Epub, Ebook

GRANDMASTER REPERTOIRE 11: BEATING 1.D4 SIDELINES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Boris Avrukh | 504 pages | 16 Apr 2013 | Quality Chess UK LLP | 9781907982125 | English | Glasgow, United Kingdom Grandmaster Repertoire 11: Beating 1.D4 Sidelines PDF Book Boris Awruch. Nc6, Legpuzzel Accessoires. Chess tactics from scratch, Weteschnik paperback. Each player is introduced with an illuminating profile, and then four of his or her finest games are explained in depth. Boeken per onderwerp. Book Edition Best Sellers. Absolutely the best I have ever seen in this price range. Phone support will be available after December 28th. Beating 1. Und das ist auch gut so. Table Top Chess Computers. View cart My Account. It is rare to find items crafted so well and I will certainly recommend The House of Staunton to others. To Exchange or Not? Most players are comfortable using their favourite defence against 1. Nf3 e6 12 Rare 3rd Moves 13 3. Grandmaster Repertoire Shogi spellen. The pictures looked great, but they don't do this set justice. All of our luxury chess products, including our chess pieces, chess boards and chess sets, have been produced with the discerning chess collector in mind. I hand waxed them as you instructed, and they are truly exceptional. Sb5 Ta5 usw. Vierbauernangriff 5. Nd2 in the mainline Fianchetto Benoni with Be2 0—0 The Pirc Defence - hardcover. Add to Watchlist Unwatch. Semi-Slawisch 18 Artikel. Show Less Show More. Hundreds of novelties Thorough coverage of virtually all relevant lines and move orders Compatible with all major defences after both 1. Spanisch 69 Artikel. Thinking inside the box.