The Last Flight of Beaufort W.6530, Which Crashed Into Barnstaple Bay Off North Devon on 10 June 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EARLY BIRDS OVER YORKSHIRE © by Hilary Dyson

From Oak Leaves, Part 3, Summer 2002 - published by Oakwood and District Historical Society [ODHS] EARLY BIRDS OVER YORKSHIRE © By Hilary Dyson 'Entrance to Olympia Works in 1915' Very soon, in 2003, we will be celebrating 100 years of powered flight and many memories of previous flyers and their bravery in taking off into space will be recalled. The story of flying in Yorkshire might be said to have started back in the 18th century. A certain gentleman called George Cayley who lived near Scarborough took an interest in many things one of which was flying. Cayley (1773-1857) had a technical education in London and on his return to his Brompton home he set up a workshop in which he eventually produced a 5ft glider in 1804. He then spent some five years developing a prototype manual glider with 200 sq ft of wingspan. But it was to be many years later that he felt ready to test it out. The test flight didn't take place till 1848. Even then he did not risk his own life he persuaded a young boy, his name was not recorded, who was launched into the air in a series of hops over a few yards. Cayley was to be 80 years old when he tried again with the help this time of his coachman. The coachman called John Appleby was not keen to change his occupation. But Cayley was elated however when a very short flight of about 500 yards was achieved. The coachman, no doubt worried that he might be asked for a repeat performance, gave in his notice, saying that he had been hired to drive a coach not to be catapulted into the air. -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

Military Aircraft Crash Sites in South-West Wales

MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH-WEST WALES Aircraft crashed on Borth beach, shown on RAF aerial photograph 1940 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For Cadw DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2012/5 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO. 105344 DAT 115C Mawrth 2013 March 2013 MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH- WEST WALES Gan / By Felicity Sage, Marion Page & Alice Pyper Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. 504616) CADEIRYDD CHAIRMAN: Prof. B C Burnham. CYFARWYDDWR DIRECTOR: K MURPHY BA MIFA SUMMARY Discussions amongst the 20th century military structures working group identified a lack of information on military aircraft crash sites in Wales, and various threats had been identified to what is a vulnerable and significant body of evidence which affect all parts of Wales. -

Airwork Limited

AN APPRECIATION The Council of the Royal Aeronautical Society wish to thank those Companies who, by their generous co-operation, have done so much to help in the production of the Journal ACCLES & POLLOCK LIMITED AIRWORK LIMITED _5£ f» g AIRWORK LIMITED AEROPLANE & MOTOR ALUMINIUM ALVIS LIMITED CASTINGS LTD. ALUMINIUM CASTINGS ^-^rr AIRCRAFT MATERIALS LIMITED ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY MOTORS LTD. STRUCTURAL MATERIALS ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY and COMPONENTS AIRSPEED LIMITED SIR W. G. ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH AIRCRAFT LTD. SIR W. G. ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH AIRCRAFT LIMITED AUSTER AIRCRAFT LIMITED BLACKBURN AIRCRAFT LTD. ^%N AUSTER Blackburn I AIRCRAFT I AUTOMOTIVE PRODUCTS COMPANY LTD. JAMES BOOTH & COMPANY LTD. (H1GH PRECISION! HYDRAULICS a;) I DURALUMIN LJOC kneed *(6>S'f*ir> tttaot • AVIMO LIMITED BOULTON PAUL AIRCRAFT L"TD. OPTICAL - MECHANICAL - ELECTRICAL INSTRUMENTS AERONAUTICAL EQUIPMENT BAKELITE LIMITED BRAKE LININGS LIMITED BAKELITE d> PLASTICS KEGD. TEAM MARKS ilMilNIICI1TIIH I BRAKE AND CLUTCH LININGS T. M. BIRKETT & SONS LTD. THE BRISTOL AEROPLANE CO., LTD. NON-FERROUS CASTINGS AND MACHINED PARTS HANLEY - - STAFFS THE BRITISH ALUMINIUM CO., LTD. BRITISH WIRE PRODUCTS LTD. THE BRITISH AVIATION INSURANCE CO. LTD. BROOM & WADE LTD. iy:i:M.mnr*jy BRITISH AVIATION SERVICES LTD. BRITISH INSULATED CALLENDER'S CABLES LTD. BROWN BROTHERS (AIRCRAFT) LTD. SMS^MMM BRITISH OVERSEAS AIRWAYS CORPORATION BUTLERS LIMITED AUTOMOBILE, AIRCRAFT AND MARITIME LAMPS BOM SEARCHLICHTS AND MOTOR ACCESSORIES BRITISH THOMSON-HOUSTON CO., THE CHLORIDE ELECTRICAL STORAGE CO. LTD. LIMITED (THE) Hxtie AIRCRAFT BATTERIES! Magnetos and Electrical Equipment COOPER & CO. (B'HAM) LTD. DUNFORD & ELLIOTT (SHEFFIELD) LTD. COOPERS I IDBSHU l Bala i IIIIKTI A. C. COSSOR LIMITED DUNLOP RUBBER CO., LTD. -

List of Exhibits at IWM Duxford

List of exhibits at IWM Duxford Aircraft Airco/de Havilland DH9 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (Ex; Spectrum Leisure Airspeed Ambassador 2 (EX; DAS) Ltd/Classic Wings) Airspeed AS40 Oxford Mk 1 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (AS; IWM) Avro 683 Lancaster Mk X (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 100 Vampire TII (BoB; IWM) Avro 698 Vulcan B2 (AS; IWM) Douglas Dakota C-47A (AAM; IWM) Avro Anson Mk 1 (AS; IWM) English Electric Canberra B2 (AS; IWM) Avro Canada CF-100 Mk 4B (AS; IWM) English Electric Lightning Mk I (AS; IWM) Avro Shackleton Mk 3 (EX; IWM) Fairchild A-10A Thunderbolt II ‘Warthog’ (AAM; USAF) Avro York C1 (AS; DAS) Fairchild Bolingbroke IVT (Bristol Blenheim) (A&S; Propshop BAC 167 Strikemaster Mk 80A (CiA; IWM) Ltd/ARC) BAC TSR-2 (AS; IWM) Fairey Firefly Mk I (FA; ARC) BAe Harrier GR3 (AS; IWM) Fairey Gannet ECM6 (AS4) (A&S; IWM) Beech D17S Staggerwing (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Fairey Swordfish Mk III (AS; IWM) Bell UH-1H (AAM; IWM) FMA IA-58A Pucará (Pucara) (CiA; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress (CiA; IWM) Focke Achgelis Fa-330 (A&S; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress Sally B (FA) (Ex; B-17 Preservation General Dynamics F-111E (AAM; USAF Museum) Ltd)* General Dynamics F-111F (cockpit capsule) (AAM; IWM) Boeing B-29A Superfortress (AAM; United States Navy) Gloster Javelin FAW9 (BoB; IWM) Boeing B-52D Stratofortress (AAM; IWM) Gloster Meteor F8 (BoB; IWM) BoeingStearman PT-17 Kaydet (AAM; IWM) Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Branson/Lindstrand Balloon Capsule (Virgin Atlantic Flyer Grumman F8F-2P Bearcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

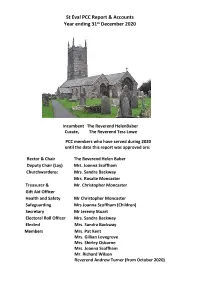

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year Ending 31St December 2020

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year ending 31st December 2020 Incumbent The Reverend HelenBaber Curate, The Reverend Tess Lowe PCC members who have served during 2020 until the date this report was approved are: Rector & Chair The Reverend Helen Baber Deputy Chair (Lay) Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Churchwardens: Mrs. Sandra Backway Mrs. Rosalie Moncaster Treasurer & Mr. Christopher Moncaster Gift Aid Officer Health and Safety Mr Christopher Moncaster Safeguarding Mrs Joanna Scoffham (Children) Secretary Mr Jeremy Stuart Electoral Roll Officer Mrs. Sandra Backway Elected Mrs. Sandra Backway Members Mrs. Pat Kent Mrs. Gillian Lovegrove Mrs. Shirley Osborne Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Mr. Richard Wilson Reverend Andrew Turner (from October 2020) The method of appointment of PCC members is set out in the Church Representation Rules. All church Attendees are encouraged to register on the Electoral Roll and stand for election to the PCC. The PCC met twice during the year. St. Eval PCC has the responsibility of co-operating with the incumbent in promoting the whole mission of the church, pastoral, evangelistic, social and ecumenical in the ecclesiastical parish. It also has maintenance responsibilities for the church, churchyard, church room, toilet block and grounds. The Parochial Church Council (PCC) is a charity excepted from registration with the Charity Commission. The church is part of the Diocese of Truro within the Church of England and is one of the four churches in the Lann Pydar Benefice. The other Parishes are St. Columb Major, St. Ervan and St. Mawgan-in-Pydar. The Parish Office, which is shared with the other 3 churches within the benefice, has now been relocated to the Rectory in St Columb Major. -

Download Our Brochure

BAE SYSTEMS BROUGH SITE A BRIEF HISTORY Originally set up by Robert Blackburn Brough was originally chosen for its in 1916, seven years after he began his access to the water for flying boats, career in aviation, the Brough site would excellent transport links to Leeds and eventually become the hub of Blackburn that renowned pair of pubs, yet it did not activities in the UK, going on to function prove as ideal as Mark Swann had first as one of the longest continuously thought, thanks to problems with tides, surviving sites of aircraft manufacturing ships and fog. However, the large site did in the world. provide the space necessary to support flying boat testing and ultimately In its 90th year, the cleanliness, allowed for major manufacturing organisation and activity level on the expansion. site is a constant source of positive comment by the many visitors from Blackburn merged with General Aircraft customer organisations, local industry Limited in 1949 and was renamed and other parts of BAE and motivation Blackburn and General Aircraft Limited. by the workforce continues in the proud However, by 1959 it had reverted back to Brough tradition established by Robert Blackburn Aircraft Limited. Blackburn himself. Finally, the company was absorbed into Hawker Siddeley in 1960 and the Blackburn name was dropped in 1963. 1914-18 - WW1, THE ROYAL 1955 - ROBERT 2000’s - THE COMMUNITY NAVY & THE WAR EFFORT BLACKBURN STEPS DOWN Over the years many changes have AS MANAGING DIRECTOR taken place at the Brough factory. During WW1, Blackburn was given the The company’s achievements have job of converting and providing aircraft By the early 1950’s Robert Blackburn had depended first and last upon its people, for the Royal Navy. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Cliffs of Dover Blenheim

BRISTOL BLENHEIM IV GUIDE BY CHUCK 1 (Unit) SPITFIRE HURRICANE BLENHEIM TIGER MOTH BF.109 BF.110 JU-87B-2 JU-88 HE-111 G.50 BR.20M Mk Ia 100 oct Mk IA Rotol 100oct Mk IV DH.82 E-4 C-7 STUKA A-1 H-2 SERIE II TEMPERATURES Water Rad Min Deg C 60 60 - - 40 60 38 40 38 - - Max 115 115 100 90 95 90 95 Oil Rad (OUTBOUND) Min Deg C 40 40 40 - 40 40 30 40 35 50 50 Max 95 95 85 105 85 95 80 95 90 90 Cylinder Head Temp Min Deg C - - 100 - - - - - - 140 140 Max 235 240 240 ENGINE SETTINGS Takeoff RPM RPM 3000 3000 2600 FINE 2350 2400 2400 2300 2400 2400 2520 2200 Takeoff Manifold Pressure UK: PSI +6 +6 +9 BCO ON See 1.3 1.3 1.35 1.35 1.35 890 820 BCO ON GER: ATA ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge • BLABLALBLABClimb RPM RPM 2700 2700 2400 COARSE 2100 2300 2300 2300 2300 2300 2400 2100 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX 30 min MAX Climb Manifold Pressure UK: PSI +6 +6 +5 See 1.23 1.2 1.15 1.15 1.15 700 740 GER: ATA ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge Normal Operation/Cruise RPM 2700 2600 2400 COARSE 2000 2200 2200 2200 2100 2200 2100 2100 RPM Normal Operation/Cruise UK: PSI +3 +4 +3.5 See 1.15 1.15 1.1 1.1 1.10 590 670 GER: ATA Manifold Pressure ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge Combat RPM RPM 2800 2800 2400 COARSE 2100 2400 2400 2300 2300 2300 2400 2100 Combat Manifold Pressure UK: PSI +6 +6 +5 See 1.3 1.3 1.15 1.15 1.15 700 740 GER: ATA ITA: mm HG RPM Gauge 5 min MAX 5 min MAX Emergency Power/ Boost RPM 2850 2850 2600 COARSE 2350 2500 2400 2300 2400 2400 2520 2200 RPM @ km 5 min MAX 5 min MAX 5 min MAX 1 min MAX 5 min MAX 1 min MAX 1 min MAX 1 min MAX 3 min -

Song of the Beauforts

Song of the Beauforts Song of the Beauforts No 100 SQUADRON RAAF AND BEAUFORT BOMBER OPERATIONS SECOND EDITION Colin M. King Air Power Development Centre © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Approval has been received from the owners where appropriate for their material to be reproduced in this work. Copyright for all photographs and illustrations is held by the individuals or organisations as identified in the List of Illustrations. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release, distribution unlimited. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. First published 2004 Second edition 2008 Published by the Air Power Development Centre National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: King, Colin M. Title: Song of the Beauforts : No 100 Squadron RAAF and the Beaufort bomber operations / author, Colin M. King. Edition: 2nd ed. Publisher: Tuggeranong, A.C.T. : Air Power Development Centre, 2007. ISBN: 9781920800246 (pbk.) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Beaufort (Bomber)--History. Bombers--Australia--History World War, 1939-1945--Aerial operations, Australian--History.