Master Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

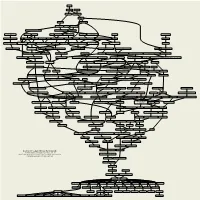

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

In Search of Enlightenment by Reading Samuel Beckett’S Waiting for Godot

LITERARIA An International Journal of New Literature Across the World ISSN: 2229-4600 VOL. 5, No. 1-2, JAN-DEC 2015 In Search of Enlightenment by Reading Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot SYED ISMYL MAHMOOD RIZVI Patna University, Patna ABSTRACT Beckett’s philosophical indebtedness has long been recognised – especially in conjunction with Dante, Descartes and Geulincx. In this article, I examine Beckettian universal values of Enlightenment, which will be exposed as self-serving mystifications that rationalize and instrumentalize the meaning of life. In this context, the awareness of the Enlightenment nature of Beckett’s writing in Waiting for Godot will be analysed along with the freedom appeal of his reader as he strives to attain the enlightenment. ‘For enlightenment, all that is needed is freedom.’ (Kant 1991 [1784]) Suppose an individual in the world which is a hard shell that he attempts to toss it away, but for what; to think beyond it, and to relocate him beyond it in order to attain enlightenment. Whenever he looks above into the sky, the high sky, the clouds, the flying birds, the stars, the moon, the sun and the cosmos, those make him to forget the hard shell for a while until his eyes fell upon it and he is recaptured. Still into the pupil of his eyes he is reflecting the cosmos. This energy within him, within anyone has vitality and potentiality to reflect the cosmos, and to look beyond the hard shell. Let’s say that he has had an enlightenment experience. Enlightenment is a fact. It is the Truth itself. -

In the Period Immediately After the Personal Catastrophe That Brought

Louis Althusser and the End of Classical Russian Marxism: Spinoza, Hegel and the Critique of Dogmatic Marxism David Campbell Abstract: An attempt to restate Marx’s critical method in terms of Spinozist dogmatic epistemology was central to Louis Althusser’s conception of Marxist philosophy. Though it is no longer necessary to argue that this ‘restatement’ had almost no ground in Marx’s own thinking, it was a highly significant expression of the essence of dialectical materialism. Through discussion of Hegel’s critique of Spinoza, it will be argued that a democratically acceptable method of criticism of the mistaken beliefs of others, such as Marx developed in Capital, must take a resolutely anti-dogmatic approach which has the principle of winning subjective conviction at its core. Keywords: critical method; dogmatism; dialectical materialism; Spinoza; Hegel; Althusser Word count: 10,300 (14,385 including apparatuses) Contact details: School of Law, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YN; 01524 594123; [email protected] Biographical note: David Campbell is a Professor of Law at Lancaster University. His research interests are in the economic, legal and social theory of regulation, and in particular in the law of contract as the general regulation of exchange. Working in areas which have throughout his professional life been dominated by Chicagoan law and economics, he has sought to advance a socialist alternative to that approach. Louis Althusser and the End of Classical Russian Marxism: Spinoza, Hegel and the Critique of Dogmatic -

Assessing the Impacts of Globalization on Kwasi Wiredu's Conceptual

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 11 No 5 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) www.richtmann.org September 2020 . Research Article © 2020 Chinenye Precious Okolisah. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 24 July 2020 / Revised: 28 August 2020 / Accepted: 1 September 2020 / Published: 23 September 2020 Assessing the Impacts of Globalization on Kwasi Wiredu’s Conceptual Decolonization in African Philosophy Chinenye Precious Okolisah Department of Philosophy, Federal University Wukari, PMB 1020, Katsina Ala Rd, Wukari, Nigeria DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2020-0054 Abstract There are two fundamental ideas in which Kwasi Wiredu apply his conceptual decolonization. These to him are two complementary things that are both negative and positive. In the negative sense, Wiredu’s conceptual decolonization is the process that seeks to avoid and reverse “through a critical self-awareness the unexamined assimilation” in the thoughts of contemporary African philosophers those conceptual frameworks that are found in western or other philosophical cultures that have influenced African ways of life and thought. On the positive side, conceptual decolonization to Wiredu involves the exploitation of the vast “resources” of African conceptual frameworks in philosophical exercises or reflections on all the basic and crucial problems of contemporary philosophy. This establishes Wiredu’s conceptual decolonization on historical foundation of the African problems through the process of colonialism. This historical trend in Africa has significant impacts on the whole of African system, which include education, politics, culture, science, technology, religion, culture, language, and thought patterns. -

Foundations of Psychology by Herman Bavinck

Foundations of Psychology Herman Bavinck Translated by Jack Vanden Born, Nelson D. Kloosterman, and John Bolt Edited by John Bolt Author’s Preface to the Second Edition1 It is now many years since the Foundations of Psychology appeared and it is long out of print.2 I had intended to issue a second, enlarged edition but the pressures of other work prevented it. It would be too bad if this little book disappeared from the psychological literature. The foundations described in the book have had my lifelong acceptance and they remain powerful principles deserving use and expression alongside empirical psy- chology. Herman Bavinck, 1921 1 Ed. note: This text was dictated by Bavinck “on his sickbed” to Valentijn Hepp, and is the opening paragraph of Hepp’s own foreword to the second, revised edition of Beginselen der Psychologie [Foundations of Psychology] (Kampen: Kok, 1923), 5. The first edition contains no preface. 2 Ed. note: The first edition was published by Kok (Kampen) in 1897. Contents Editor’s Preface �����������������������������������������������������������������������ix Translator’s Introduction: Bavinck’s Motives �������������������������� xv § 1� The Definition of Psychology ���������������������������������������������1 § 2� The Method of Psychology �������������������������������������������������5 § 3� The History of Psychology �����������������������������������������������19 Greek Psychology .................................................................19 Historic Christian Psychology ..............................................22 -

Amo on Theheterogeneity Problem

volume 19, no. 41 1. The Heterogeneity Problem september 2019 On May 6 1643, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia picked up her pen and wrote her first letter to René Descartes. The question that she poses to Descartes is one of the most devastating critiques, if not the most, of his metaphysics: How can a thinking substance, the human mind, bring about voluntary actions in a material substance, the human Amo on the body? This was not the first time that Descartes had heard this ques- tion.1 Pierre Gassendi, in the Fifth Objections to the Meditations, raises just this worry, asking Descartes to explain how “the corporeal can communicate with the incorporeal,” and, moreover, of “what relation- Heterogeneity ship may be established between the two” (AT VII.345/CSM II.239). The objection raised by Elisabeth and Gassendi has come to be known as the “heterogeneity problem,” which arises when we wonder how Problem two wholly heterogeneous substances can causally interact in any meaningful way.2 Descartes’s response to Gassendi is that the whole problem contained in such questions arises simply from a supposition that is false and cannot in any way be proved, namely that, if the soul and the body are two substances whose nature is different, this prevents them from being able to act on each other. And yet, those who admit the existence of real accidents like heat, weight and so on, have no doubt that these acci- dents can act on the body; but there is much more of a Julie Walsh difference between them and it, i.e. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://eprints.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Tracing ‘a literary fantasia’ Arnold Geulincx in the works of Samuel Beckett DAVID TUCKER DPhil University of Sussex June 2010 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature………………………………………… iii University of Sussex David Tucker DPhil English Literature Tracing ‘a literary fantasia’: Arnold Geulincx in the works of Samuel Beckett Summary This thesis investigates Beckett’s interests in the seventeenth-century philosopher Arnold Geulincx, tracing these interests first back to primary sources in Beckett’s own notes and correspondence, and then forward through his oeuvre. This first full-length study of the occasionalist philosopher in Beckett’s works reveals Geulincx as closely bound, in changeable and subtle ways, to Beckett’s altering compositional methodologies and aesthetic foci. It argues that multifaceted attentiveness to the different ways in which Geulincx is alluded to or explicitly cited in different works is required if the extent of Geulincx’ importance across Beckett’s oeuvre is to be properly understood. -

The Akan Conception of a Person Jessica Anne Sykes Dickinson College

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Honors Theses By Year Student Honors Theses 5-22-2016 The Akan Conception of a Person Jessica Anne Sykes Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_honors Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Sykes, Jessica Anne, "The Akan Conception of a Person" (2016). Dickinson College Honors Theses. Paper 225. This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AKAN CONCEPTION OF A PERSON BY JESSICA SYKES MAY 19, 2016 SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF HONOR S REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY CHAUNCEY MAHER, SUPE RVISOR SUSAN FELDMAN, READE R JIM SIAS, READER JEFF ENGELHARDT, READER Sykes Table of Contents INTROCUCTION 3 THE AKAN CONCEPTION OF PERSONS 6 WHO ARE THE AKAN? 6 WHAT DO THE AKAN THINK ABOUT PERSONS? 8 WHY THE DISPUTE IS INTERESTING 13 CHALLENGES 15 ASSESSMENT OF THE AKAN CONCEPTION OF A PERSON 16 JOHN LOCKE 16 A COMPARISON OF THE AKAN AND LOCKE 20 APPLICATION TO MODERN SITUATIONS 27 AGAINST THE AKAN CONCEPTION OF PERSONS 33 CONCLUSION 40 BIBLIOGRAPHY 43 2 Sykes IntroductIon My liFe is based on the assumption that I am a Person. This is an assumption that I have never doubted. If you are reading this, you too are a person. Or so I have been taught to assume. But why have I been taught this? What makes us PeoPle, and why can I be so sure of these “facts”? These questions came to me as I reFlected on the different ways we treat other PeoPle compared to the way we treat non-humans. -

Academic Genealogy of Tom Hendrik Koornwinder Simon Speijert Van Der Eyk Universiteit Leiden the Mathematics Genealogy Project Is a Service Of

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī Kamal al Din Ibn Yunus Nasir al-Din al-Tusi Shams ad-Din Al-Bukhari Maragheh Observatory Gregory Chioniadis 1296 Ilkhans Court at Tabriz Manuel Bryennios Theodore Metochites 1315 Gregory Palamas Nilos Kabasilas 1363 Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università degli Studi di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università degli Studi di Padova 1462 Università degli Studi di Firenze Theodoros Gazes Paolo (Nicoletti) da Venezia Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Nicole Oresme 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Mantova 1477 Università degli Studi di Firenze 1433 Constantinople Demetrios Chalcocondyles Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis 1452 Accademia Romana 1363 Université de Paris 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università degli Studi di Firenze 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1452 Mystras 1375 Université de Paris Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Georgius Hermonymus Janus Lascaris Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Jean Tagault François Dubois Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden -

Luther's Lost Books and the Myth of the Memory Cult

Luther's Lost Books and the Myth of the Memory Cult Dixon, C. S. (2017). Luther's Lost Books and the Myth of the Memory Cult. Past and Present, 234(Supplement 12), 262-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtx040 Published in: Past and Present Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © The Past and Present Society. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:26. Sep. 2021 1 Luther’s Lost Books and the Myth of the Memory Cult C. Scott Dixon On the morning of 18 February 1546, in his birthplace of Eisleben, Martin Luther died of heart failure. Just as Johann Friedrich, Elector of Saxony, had feared, and Luther himself had prophesied, his trip to the duchy of Mansfeld to settle a jurisdictional dispute had proven too much. -

RENÉ DESCARTES (1596-1650) Author: (W.W.; X.) = William Wallace (1844-1897) Encyclopedia Britannica (New York 1911) Vol

RENÉ DESCARTES (1596-1650) Author: (W.W.; X.) = William Wallace (1844-1897) Encyclopedia Britannica (New York 1911) vol. 8: 79-90. Electronic Text edited, modernized & paginated by Dr Robert A. Hatch© DESCARTES, RENÉ (1596-1650), French philosopher, was born at La Haye, in Touraine, midway between Tours and Poitiers, on the 31st of March 1596, and died at Stockholm on the 11th of February 1650. The house where he was born is still shown, and a métairie about 3 miles off retains the name of Les Cartes. His family on both sides was of Poitevin descent. Joachim Descartes, his father, having purchased a commission as counsellor in the parlement of Rennes, introduced the family into that demi-noblesse of the robe which, between the bourgeoisie and the high nobility, maintained a lofty rank in French society. He had three children, a son who afterwards succeeded to his father in the parlement, a daughter who married a M. du Crevis, and René, after whose birth the mother died. Descartes, known as Du Perron, from a small estate destined for his inheritance, soon showed an inquisitive mind. From 1604 to 1612 he studied at the school of La Flèche, which Henry IV. had lately founded and endowed for the Jesuits. He enjoyed exceptional privileges; his feeble health excused him from the morning duties, and thus early he acquired the habit of reflection in bed, which clung to him throughout life. Even then he had begun to distrust the authority of tradition and his teachers. Two years before he left school he was selected as one of the twenty-four who went forth to receive the heart of Henry IV. -

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY Prof. Anthony D

INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY SPRING 2012– RUTGERS UNIVERSITY Prof. Anthony D. Baldino Phone: 917-721-0326 e-mail: [email protected] Goals: Core Curriculum Learning Goal: This course meets goal ‘o’: ‘Examine critically philosophical and other theoretical issues concerning the nature of reality, human experience, knowledge, value, and/or cultural production.’ Assessment will be by an SAS generic rubric embedded in the evaluation criteria laid out in this syllabus. This class will introduce students to the methods and issues of philosophy focusing on basic questions of the possibility of truth and value, ethics, the existence of God, metaphysics, epistemology, and theory of mind. Office Hours: After each class – location to be determined (most likely in the classroom). Students should also feel free to contact me by phone at any point with any questions or concerns. Text: Introduction to Philosophy – Classical and Contemporary Readings – 4th or 5th ed. John Perry, Michael Bratman and John Martin Fischer Requirements: --Two Exams --Midterm Exam (30 points) --Final Exam (30 points) --Two Papers --2-3 page paper due in class March 24 (10 points) Grade will be lowered by one letter for each week late. --3-5 page paper due in class April 24 (30 points) Grade will be lowered by one letter for each week late, and no papers will be accepted after the final. Grading: The following guideline will be used to assess papers and exams Exceeds the Meets the Does Not Meet the Standard Standard Standard Comprehension of Firm grasp of Moderate grasp